Lesson 3. Harmony in music

Contents

One of the most important concepts in music is harmony. Melody and harmony are closely related. It is the harmonious combination of sounds that gives the melody the right to be called a melody.

You already have all the basic knowledge necessary for this. In particular, you know what tone, semitone and scale steps are, which will help you deal with such a basic object of harmony as intervals, as well as modes and tonality.

Confidentially, by the end of this lesson, you will have gained some of the basic knowledge you need to write pop and rock music. Until then, let’s get to learning!

What is harmony

These aspects of harmony are closely interrelated. A melody is perceived as harmonious when it is built taking into account certain patterns of sound combinations. To understand these patterns, we need to get acquainted with the objects of harmony, i.e. categories, one way or another united by the concept of “harmony”.

Intervals

The basic object of harmony is the interval. An interval in music refers to the distance in semitones between two musical sounds. We met halftones in previous lessons, so now there should be no difficulties.

Varieties of simple intervals:

So, simple intervals mean the intervals between sounds within an octave. If the interval is greater than an octave, such an interval is called a composite interval.

Varieties of compound intervals:

The first and main question: how to remember it? Actually it’s not that difficult.

How and why to remember intervals

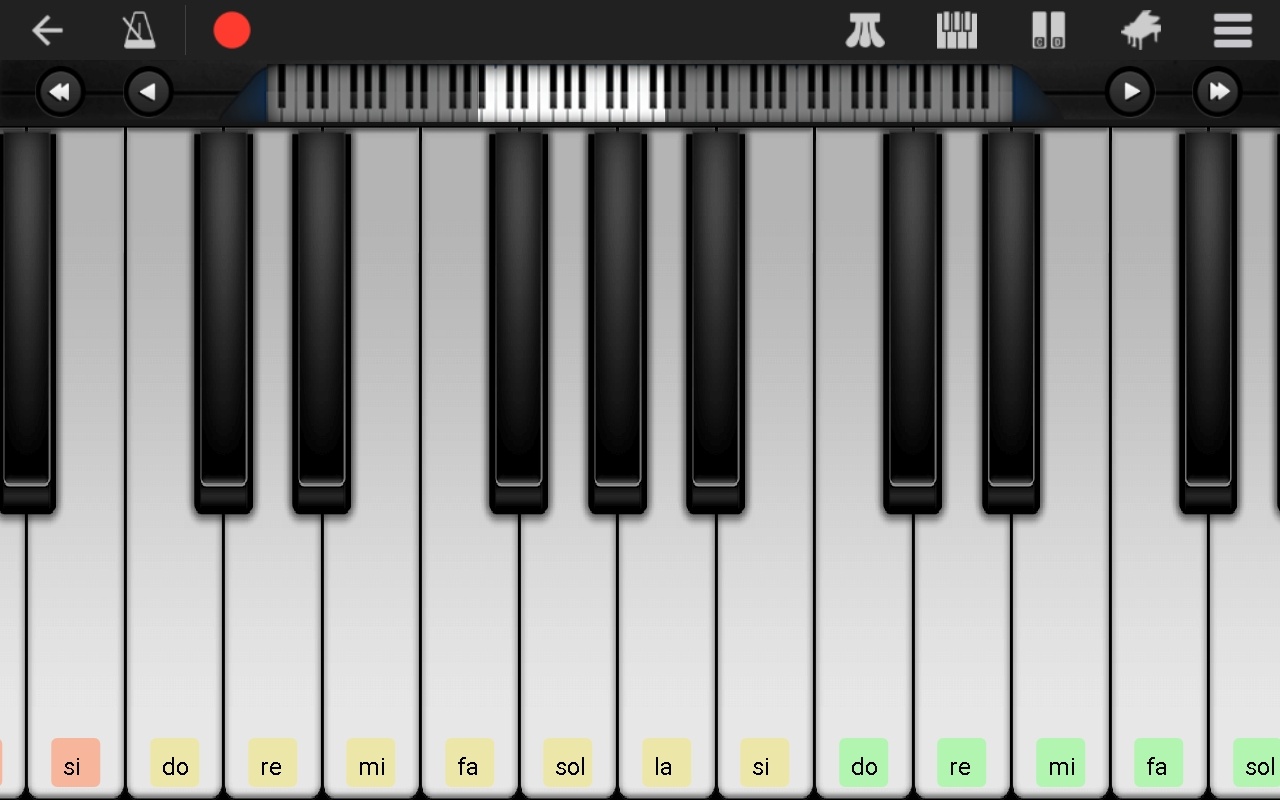

From the general development, you probably know that the development of memory is facilitated by the training of fine motor skills of the fingers. If you train fine motor skills on the piano keyboard, you will develop not only memory, but also musical ear. We recommend perfect piano app, which can be downloaded from Google Play:

Then it remains for you to regularly play all the above intervals and pronounce their names aloud. You can start with any key, in this case it does not matter. It is important to accurately count the number of semitones. If you play one key 2 times – this is an interval of 0 semitones, two adjacent keys – this is an interval of 1 semitone, after one key – 2 semitones, etc. We add that in the application settings you can set the number of keys on the screen that is convenient for you personally.

The second and no less burning question is why? Why do you need to know and hear intervals, except for mastering the basics of music theory? But here it is not so much a matter of theory as of practice. When you learn to recognize all these intervals by ear, you will easily pick up any melody you like by ear, both for voice and for playing a musical instrument. Actually, most of us pick up a guitar or violin, sit down at the piano or drum kit just to perform our favorite pieces.

And, finally, knowing the names of the intervals, you can easily find out what it is about if you hear that a piece of music is built, for example, on fifth chords. This, by the way, is a common practice in rock music. You just need to remember that a pure fifth is 7 semitones. Therefore, simply add 7 semitones to each sound made by the bass guitar, and you get the fifth chords used in the work you like. We recommend that you focus on the bass, because it is usually more clearly audible, which is important for beginners.

To hear the main sound (tonic), you need to work on the development of an ear for music. You’ve already started doing this if you’ve downloaded Perfect Piano and played the intervals. In addition, you can use this application or a real musical instrument to try to hear which note sounds in unison with the tonic (main sound) of the piece of music you are interested in. To do this, simply press the keys in a row within the limits of a large and small octave, or play all the notes on the guitar, pressing the 6th and 5th (bass!) strings sequentially at each fret. You will notice that one of the notes is clearly in unison. If your hearing has not failed you, this is the tonic. To make sure your ears are right, find that note one or two octaves higher and play it. If it’s the tonic, you’ll be in tune with the melody again.

Often you can find the designation of intervals not in semitones, but in steps. Here we have in mind only the main steps of the scale, i.e. “do”, “re”, “mi”, “fa”, “sol”, “la”, “si”. Increased and reduced steps, i.e. sharps and flats are not included in the calculation, so the number of steps in the interval differs from the number of semitones. In principle, counting intervals in steps is convenient for those who are going to play the piano, because on the keyboard the main steps of the scale correspond to the white keys, and this system looks very visual.

It is more convenient for everyone else to consider intervals in semitones, because on other musical instruments, the main steps of the scale are not visually distinguished in any way. But, for example, frets are highlighted on the guitar. They are limited by the so-called “nuts” located across the guitar neck, on which the strings are stretched. Fret numbering in progress from the headstock:

By the way, the word “cord” has many meanings and is directly related to the theme of harmony.

Frets

The second central element of harmony is harmony. As music theory developed, different definitions of mode dominated. It was understood as a system of combining tones, as an organization of tones in their interaction, as a pitch system of subordinating tones. Now the definition of mode is more accepted as a system of pitch connections, united with the help of a central sound or consonance.

If this is still difficult, just imagine, by analogy with the outside world, that harmony in music is when sounds seem to get along with each other. Just as some families can be said to live in harmony, so certain musical sounds can be said to be in harmony with each other.

In the applied sense, the term “mode” is most often used in relation to minor and major. The word “minor” comes from the Latin mollis (translated as “soft”, “gentle”), so minor pieces of music are perceived as lyrical or even sad. The word “major” comes from the Latin major (translated as “larger”, “senior”), so major musical works are perceived more as assertive and optimistic.

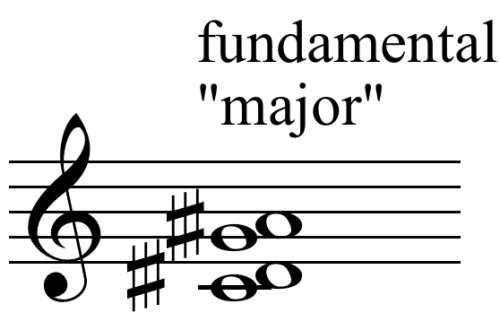

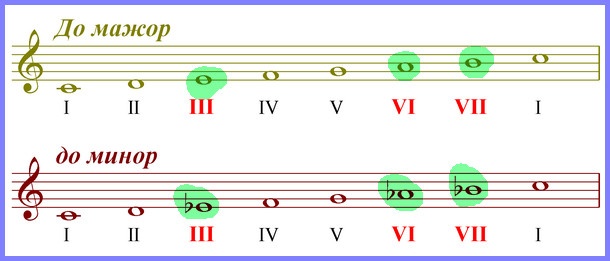

Thus, the main types of modes are minor and major. Marked in green for clarity steps (notes) frets, which are different for minor and major:

At the philistine level, there is a simplified gradation and such a characteristic of the minor as “sad”, and the major as “cheerful”. This is very conditional. It is not at all necessary that a minor piece will always be sad, and a major melody will always sound joyful. Moreover, this trend can be traced at least since the 18th century. So, Mozart’s work “Sonata No. 16 in C Major” sounds very disturbing in places, and the incendiary song “A Grasshopper Sat in the Grass” is written in a minor key.

Both minor and major modes begin with the tonic – the main sound or the main step of the mode. Next comes a combination of stable and unstable sounds in its own sequence for each fret. Here you can draw an analogy with the construction of a brick wall. For the wall, both solid bricks and a semi-liquid binder mixture are needed, otherwise the structure will not acquire the desired height and will not be kept in a given state.

Both in major and in minor there are 3 stable steps: 1st, 3rd, 5th. The remaining steps are considered unstable. In the musical literature, one can come across such terms as the “gravitation” of sounds, or “the desire for resolution.” To put it simply, the melody cannot be cut off on an unstable sound, but always must be completed on a stable one.

Later in the lesson, you will come across such a term as “chord”. To avoid confusion, let’s say right away that stable scale steps and basic chord steps are not identical concepts. Those who want to quickly start playing a musical instrument should first use ready-made chord fingerings, and the principles of construction will become clear as you master the playing techniques and simple melodies.

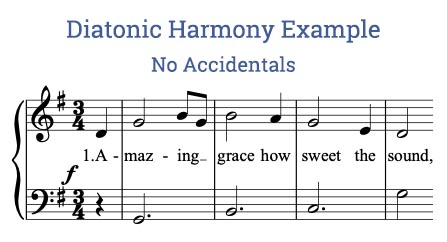

In addition, in special music publications, you may come across such mode names as Ionian, Dorian, Phrygian, Lydian, Mixolydian, Aeolian and Locrian. These are the modes that are built on the basis of the major scale, and one of the degrees of the scale is used as the tonic. They are also called natural, diatonic or Greek.

They are called Greek because their names come from the tribes and nationalities that inhabited the territory of Ancient Greece. Actually, the musical traditions that underlie each of the named diatonic modes have been counting down since those times. If you intend to write music in the future, you might want to come back to this question later, when you understand how to build a major scale. In addition, it is worth studying the material “Diatonic Frets for Beginners» with audio examples of the sound of each of them [Shugaev, 2015]:

In the meantime, let’s summarize the concepts of major and minor modes that are more applicable in practice. In general, when we encounter the phrases “major mode” or “minor mode”, we mean the modes of harmonic tonality. Let’s figure out what tonality is in general and harmonic tonality in particular.

Key

So what is tone? As with many other musical terms, there are various definitions for key. The term itself is derived from the Latin word tone. In anatomy and physiology, this means prolonged stimulation of the nervous system and tension of muscle fibers without leading to fatigue.

Everyone understands perfectly well what the phrase “to be in good shape” means. In music, things are about the same. Melody and harmony are, relatively speaking, in good shape throughout the entire duration of the musical composition.

We already know that any mode – minor or major – begins with the tonic. Both minor and major modes can be tuned from any sound that will be taken as the main sound, i.e. the tonic of the work. The height position of the fret with its reference to the height of the tonic is called tonality. Thus, the formation of tonality can be reduced to a simple formula.

Tone formula:

Key = tonic + fret

That is why the definition of tonality is often given as the principle of mode, the main category of which is the tonic. Now let’s recap.

The main types of keys:

| ✔ | Minor. |

| ✔ | Major. |

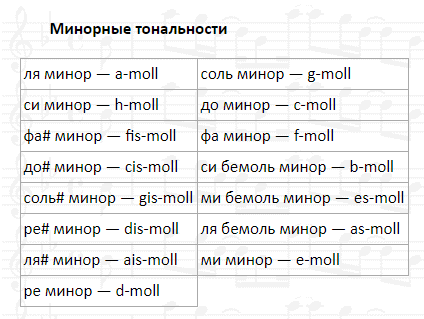

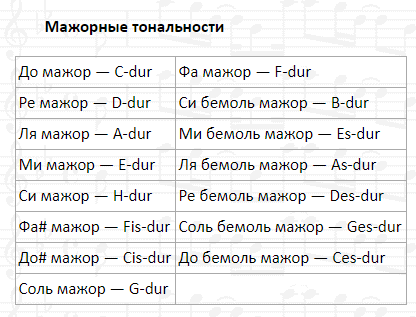

What does this tonality formula and these types of tonality mean in practice? Let’s say we hear a minor piece of music, where the minor scale is built from the note “la”. This will mean that the key of the work is “A minor” (Am). Let’s say right away that to designate a minor key, the Latin m is added to the tonic. In other words, if you see the designation Cm, it is “C minor”, if Dm is “D minor”, Em – respectively, “E minor”, etc.

If you see in the “tonality” column just large letters denoting a particular note – C, D, E, F and others – this means that you are dealing with a major key, and you have a work in the key of “C major”, “ D major”, “E major”, “F major”, etc.

Decreased or increased relative to the main step of the scale, the tonality is indicated by the sharp and flat icons known to you. If you see a key entry in the format, for example, F♯m or G♯m, this means that you have a piece in the key of F sharp minor or G sharp minor. The reduced key will be with a flat sign, i.e. A♭m (A-flat minor”), B♭m (“B-flat minor”), etc.

In a major key, there will be a sharp or flat sign next to the tonic designation without additional characters. For example, C♯ (“C-sharp major”), D♯ (“D-sharp major”), A♭ (“A-flat major”), B♭ (“B-flat major”), etc. You can find other designations of keys. For example, when the word major or minor is added to the note, and instead of the sharp or flat sign, the word sharp or flat is added.

These are presentation options. minor keys:

Further notation options major keys:

All of the above keys are harmonic, i.e. determining the harmony of music.

So, harmonic tonality is a major-minor system of tonal harmony.

There are other types of tones. Let’s list them all.

Varieties of tones:

In the last variety, we came across the term “tertia”. Earlier we found out that the third can be small (3 semitones) or large (4 semitones). Here we come to such a concept as “gamma”, which needs to be dealt with in order to finally understand what modes, keys and other components of harmony are.

Scales

Everyone heard about scales at least once, with whom one of their acquaintances attended a music school. And, as a rule, I heard in a negative context – they say, boring, tiring. And, in general, it is not clear why they learn. To begin with, let’s say that a scale is a sequence of sounds in a key. In other words, if you sequentially build all the sounds of the tonality, starting with the tonic, this will be the scale.

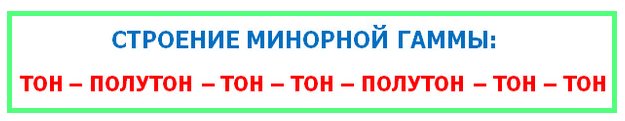

Each of the keys – minor and major – is built according to its own patterns. Here we again need to remember what a semitone and a tone are. Remember, a tone is 2 semitones. Now you can go to building a gamma:

Remember this sequence for major scales: tone-tone-semitone-tone-tone-tone-semitone. Now let’s see how to build a major scale using the example of a scale “C major”:

You already know the notes, so you can see from the picture that the C major scale includes the notes C (do), D (re), E (mi), F (fa), G (sol), A (la), B (si), C (to). Let’s move on to minor scales:

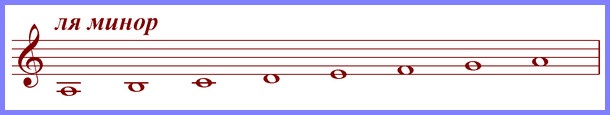

Remember the scheme for constructing minor scales: tone-semitone-tone-tone-semitone-tone-tone. Let’s see how to build a major scale using the example of a scale “La Minor”:

To make it easier to remember, please note that in the major scale, first comes the major third (4 semitones or 2 tones), and then the small one (3 semitones or semitone + tone). In the minor scale, first comes the small third (3 semitones or a tone + semitone), and then the large third (4 semitones or 2 tones).

In addition, you can see that the scale “A minor” includes the same notes as “C major”, it only starts with the note “A”: A, B, C, D, E, F, G, A. A little earlier, we cited these keys as an example of parallel ones. It seems that now is the most opportune moment to dwell on parallel keys in more detail.

We found out that parallel keys are keys with completely coinciding notes and the difference between the tonics of the minor and major keys is 3 semitones (minor third). Due to the fact that the notes completely coincide, the parallel keys have the same number and type of signs (sharps or flats) at the key.

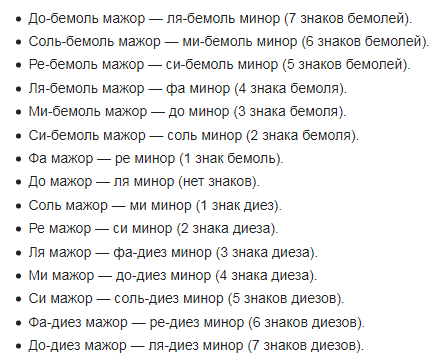

We focus on this because in the specialized literature one can find the definition of parallel keys as those that have the same number and type of signs at the key. As you can see, these are quite simple and understandable things, but stated in a scientific language. A complete list of such tones presented below:

Why do we need this information in practical music making? Firstly, in any incomprehensible situation, you can play the tonic of a parallel key and diversify the melody. Secondly, in this way you will make it easier for yourself to select the melody and chords, if you do not yet distinguish by ear all the nuances of the sound of a piece of music. Knowing the key, you will simply limit your search for suitable chords to those that fit this key. How do you define it? Here you need to do two clarifications:

| 1 | first: Chords are written in the same format as the key. The chord “A minor” and the key “A minor” in the record look like Am; the chord “C major” and the key “C major” are written as C; and so with all other keys and chords. |

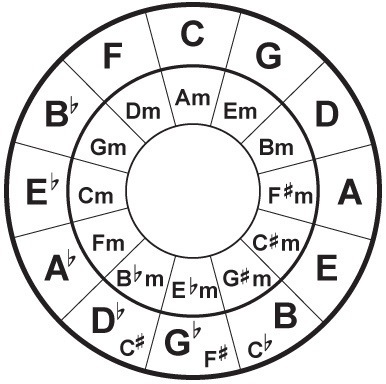

| 2 | Second: Matching chords are located next to each other on the circle of fifths and fourths. This does not mean that it is impossible to find a suitable chord at some distance from the main one. This means that you will definitely not be mistaken if you first compose those chords and keys that are next to each other. |

This scheme is called the fifth-quart circle because clockwise the main sounds of the keys are separated from each other by a fifth (7 semitones), and counterclockwise – by a perfect fourth (5 semitones). 7 + 5 = 12 semitones, i.e. vicious circle forms an octave:

By the way, such an approach as arranging adjacent chords can help out novice composers who have awakened a passion for writing, but the study of music theory is still at an early stage. And composers who have achieved fame also practice this approach. For clarity, we present a few examples.

Choosing chords for a song “A Star Called Sun” Kino group:

And here are examples from modern pop music:

Selection chords for the song “Disarmed” performed by Polina Gagarina:

And the fairly recent premiere of 2020 clearly shows that the trend is alive:

Choosing chords for a song “Naked King” performed by Alina Grosu:

For those who are in a hurry to start playing, we can advise video on frets and scales from a musician and teacher with experience Alexander Zilkov:

And for those who want to delve deeper into the theory and learn more about harmony in music, we recommend the book “Essays on Modern Harmony”, which was written many years ago by an art critic, teacher of the Moscow Conservatory Yuri Kholopov, and which is still relevant [Yu. Kholopov, 1974].

We recommend that absolutely everyone take a verification test and, if necessary, fill in the gaps in knowledge before moving on to the next lesson. This knowledge will definitely come in handy, so we wish you good luck!

Lesson comprehension test

If you want to test your knowledge on the topic of this lesson, you can take a short test consisting of several questions. Only 1 option can be correct for each question. After you select one of the options, the system automatically moves on to the next question. The points you receive are affected by the correctness of your answers and the time spent on passing. Please note that the questions are different each time, and the options are shuffled.

Now let’s move on to polyphony and mixing.