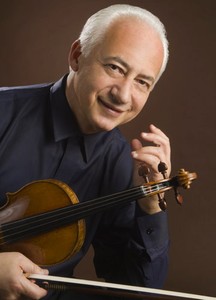

Leonid Kogan |

Leonid Kogan

Kogan’s art is known, appreciated and loved in almost all countries of the world – in Europe and Asia, in the USA and Canada, South America and Australia.

Kogan is a strong, dramatic talent. By nature and artistic individuality, he is the opposite of Oistrakh. Together they constitute, as it were, the opposite poles of the Soviet violin school, illustrating its “length” in terms of style and aesthetics. With stormy dynamics, pathetic elation, emphasized conflict, bold contrasts, Kogan’s play seems surprisingly in tune with our era. This artist is sharply modern, living with the unrest of today, sensitively reflecting the experiences and anxieties of the world around him. A close-up performer, alien to smoothness, Kogan seems to be striving towards conflicts, resolutely rejecting compromises. In the dynamics of the game, in tart accents, in the ecstatic drama of intonation, he is related to Heifetz.

Reviews often say that Kogan is equally accessible to the bright images of Mozart, the heroism and tragic pathos of Beethoven, and the juicy brilliance of Khachaturian. But to say so, without shading the features of the performance, means not to see the individuality of the artist. In relation to Kogan, this is especially unacceptable. Kogan is an artist of the brightest individuality. In his playing, with an exceptional sense of the style of the music he performs, something uniquely his own, “Kogan’s”, always captivates, his handwriting is firm, resolute, imparting a clear relief to each phrase, the contours of melos.

Striking is the rhythm in Kogan’s play, which serves as a powerful dramatic tool for him. Chased, full of life, “nerve” and “tonal” tension, Kogan’s rhythm truly constructs the form, giving it artistic completeness, and giving power and will to the development of music. Rhythm is the soul, the life of the work. Rhythm itself is both a musical phrase and something by which we satisfy the aesthetic needs of the public, by which we influence it. Both the character of the idea and the image – everything is carried out through rhythm, ”Kogan himself speaks about rhythm.

In any review of Kogan’s game, the decisiveness, masculinity, emotionality and drama of his art invariably stand out in the first place. “Kogan’s performance is an agitated, assertive, passionate narration, a speech flowing tensely and passionately.” “Kogan’s performance strikes with inner strength, hot emotional intensity and at the same time with softness and a variety of shades,” these are the usual characteristics.

Kogan is unusual for philosophy and reflection, common among many contemporary performers. He seeks to reveal in music mainly its dramatic effectiveness and emotionality and through them to approach the inner philosophical meaning. How revealing in this sense are his own words about Bach: “There is much more warmth and humanity in him,” Kogan says, than experts sometimes think, imagining Bach as “the great philosopher of the XNUMXth century.” I would like not to miss the opportunity to emotionally convey his music, as it deserves.

Kogan has the richest artistic imagination, which is born from the direct experience of music: “Each time he discovers in the work still seemingly unknown beauty and believes about it to the listeners. Therefore, it seems that Kogan does not perform music, but, as it were, creates it again.

Patheticism, temperament, hot, impulsive emotionality, romantic fantasy do not prevent Kogan’s art from being extremely simple and strict. His game is devoid of pretentiousness, mannerisms, and especially sentimentality, it is courageous in the full sense of the word. Kogan is an artist of amazing mental health, an optimistic perception of life, which is noticeable in his performance of the most tragic music.

Usually, Kogan’s biographers distinguish two periods of his creative development: the first one with a focus mainly on virtuoso literature (Paganini, Ernst, Venyavsky, Vietanne) and the second one with a re-emphasis on a wide range of classical and modern violin literature, while maintaining a virtuoso line of performance.

Kogan is a virtuoso of the highest order. Paganini’s first concerto (in the author’s edition with E. Sore’s rarely played most difficult cadenza), his 24 capricci played in one evening, testify to a mastery that only a few achieve in the world violin interpretation. During the formative period, says Kogan, I was greatly influenced by the works of Paganini. “They were instrumental in adapting the left hand to the fretboard, in understanding fingering techniques that were not ‘traditional’. I play with my own special fingering, which differs from the generally accepted. And I do this based on the timbre possibilities of the violin and phrasing, although often not everything here is acceptable in terms of methodology.”

But neither in the past nor in the present Kogan was fond of “pure” virtuosity. “A brilliant virtuoso, who mastered a huge technique even in his childhood and youth, Kogan grew up and matured very harmoniously. He comprehended the wise truth that the most dizzying technique and the ideal of high art are not identical, and that the first must go “in service” to the second. In his performance, Paganini’s music acquired an unheard of drama. Kogan perfectly feels the “components” of the creative work of the brilliant Italian – a vivid romantic fantasy; contrasts of melos, filled either with prayer and sorrow, or with oratorical pathos; characteristic improvisation, features of dramaturgy with climaxes reaching the limit of emotional stress. Kogan and in virtuosity went “into the depths” of music, and therefore the onset of the second period came as a natural continuation of the first. The path of the artistic development of the violinist was actually determined much earlier.

Kogan was born on November 14, 1924 in Dnepropetrovsk. He began learning to play the violin at the age of seven at a local music school. His first teacher was F. Yampolsky, with whom he studied for three years. In 1934 Kogan was brought to Moscow. Here he was accepted into a special children’s group of the Moscow Conservatory, in the class of Professor A. Yampolsky. In 1935, this group formed the main core of the newly opened Central Children’s Music School of the Moscow State Conservatory.

Kogan’s talent immediately attracted attention. Yampolsky singled him out from all his pupils. The professor was so passionate and attached to Kogan that he settled him at his home. Constant communication with the teacher gave a lot to the future artist. He had the opportunity to use his advice every day, not only in the classroom, but also during homework. Kogan inquisitively looked at Yampolsky’s methods in his work with students, which later had a beneficial effect in his own teaching practice. Yampolsky, one of the outstanding Soviet educators, developed in Kogan not only the brilliant technique and virtuosity that astonishes the modern, so sophisticated public, but also laid high principles of performance in him. The main thing is that the teacher correctly formed the personality of the student, either restraining the impulses of his willful nature, or encouraging his activity. Already in the years of study in Kogan, a tendency to a large concert style, monumentality, dramatic-strong-willed, courageous warehouse of the game was revealed.

They started talking about Kogan in musical circles very soon – literally after the very first performance at the festival of students of children’s music schools in 1937. Yampolsky used every opportunity to give concerts of his favorite, and already in 1940 Kogan played the Brahms Concerto for the first time with the orchestra. By the time he entered the Moscow Conservatory (1943), Kogan was well known in musical circles.

In 1944 he became a soloist of the Moscow Philharmonic and made concert tours around the country. The war is not yet over, but he is already on his way to Leningrad, which has just been liberated from the blockade. He performs in Kyiv, Kharkov, Odessa, Lvov, Chernivtsi, Baku, Tbilisi, Yerevan, Riga, Tallinn, Voronezh, the cities of Siberia and the Far East, reaching Ulaanbaatar. His virtuosity and striking artistry amaze, captivate, excite listeners everywhere.

In the autumn of 1947, Kogan participated in the I World Festival of Democratic Youth in Prague, winning (together with Y. Sitkovetsky and I. Bezrodny) the first prize; in the spring of 1948 he graduated from the conservatory, and in 1949 he entered graduate school.

Postgraduate study reveals another feature in Kogan – the desire to study performed music. He not only plays, but writes a dissertation on the work of Henryk Wieniawski and takes this work extremely seriously.

In the very first year of his postgraduate studies, Kogan amazed his listeners with the performance of 24 Paganini Capricci in one evening. The interests of the artist in this period are focused on virtuoso literature and masters of virtuoso art.

The next stage in Kogan’s life was the Queen Elizabeth Competition in Brussels, which took place in May 1951. The world press spoke about Kogan and Vayman, who received the first and second prizes, as well as those awarded with gold medals. After the phenomenal victory of the Soviet violinists in 1937 in Brussels, which nominated Oistrakh to the ranks of the first violinists in the world, this was perhaps the most brilliant victory of the Soviet “violin weapon”.

In March 1955 Kogan went to Paris. His performance is regarded as a major event in the musical life of the French capital. “Now there are few artists all over the world who could compare with Kogan in terms of the technical perfection of performance and the richness of his sound palette,” wrote the critic of the newspaper “Nouvelle Litterer”. In Paris, Kogan purchased a wonderful Guarneri del Gesu violin (1726), which he has been playing ever since.

Kogan gave two concerts in the Hall of Chaillot. They were attended by more than 5000 people – members of the diplomatic corps, parliamentarians and, of course, ordinary visitors. Conducted by Charles Bruck. Concertos by Mozart (G major), Brahms and Paganini were performed. With the performance of the Paganini Concerto, Kogan literally shocked the audience. He played it in its entirety, with all the cadences that frighten many violinists. The Le Figaro newspaper wrote: “By closing your eyes, you could feel that a real sorcerer was performing in front of you.” The newspaper noted that “strict mastery, purity of sound, richness of timbre especially delighted the listeners during the performance of the Brahms Concerto.”

Let’s pay attention to the program: Mozart’s Third Concerto, Brahms’ Concerto and Paganini’s Concerto. This is the most frequently performed by Kogan subsequently (up to the present day) cycle of works. Consequently, the “second stage” – the mature period of Kogan’s performance – began in the mid-50s. Already not only Paganini, but also Mozart, Brahms become his “horses”. Since that time, the performance of three concertos in one evening is a common occurrence in his concert practice. What the other performer goes for as an exception, for Kogan the norm. He loves cycles – six sonatas by Bach, three concertos! In addition, the concerts included in the program of one evening, as a rule, are in sharp contrast in style. Mozart is compared with Brahms and Paganini. Of the most risky combinations, Kogan invariably comes out the winner, delighting listeners with a subtle sense of style, the art of artistic transformation.

In the first half of the 50s, Kogan was intensively busy expanding his repertoire, and the culmination of this process was the grandiose cycle “Development of the Violin Concerto”, given by him in the 1956/57 season. The cycle consisted of six evenings, during which 18 concerts were performed. Before Kogan, a similar cycle was performed by Oistrakh in 1946-1947.

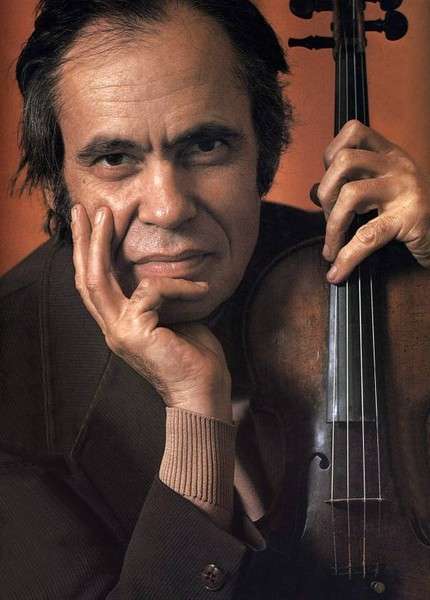

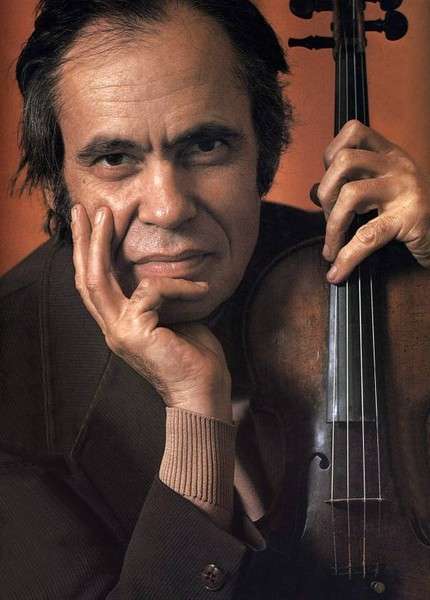

Being by the nature of his talent an artist of a large concert plan, Kogan begins to pay much attention to chamber genres. They form a trio with Emil Gilels and Mstislav Rostropovich, performing open chamber evenings.

His permanent ensemble with Elizaveta Gilels, a bright violinist, laureate of the first Brussels competition, who became his wife in the 50s, is magnificent. Sonatas by Y. Levitin, M. Weinberg and others were written especially for their ensemble. At present, this family ensemble has been enriched by one more member – his son Pavel, who followed in the footsteps of his parents, becoming a violinist. The whole family gives joint concerts. In March 1966, their first performance of the Concerto for three violins by the Italian composer Franco Mannino took place in Moscow; The author specially flew to the premiere from Italy. The triumph was complete. Leonid Kogan has a long and strong creative partnership with the Moscow Chamber Orchestra headed by Rudolf Barshai. Accompanied by this orchestra, Kogan’s performance of the Bach and Vivaldi concertos acquired a complete ensemble unity, a highly artistic sound.

In 1956 South America listened to Kogan. He flew there in mid-April with pianist A. Mytnik. They had a route – Argentina, Uruguay, Chile, and on the way back – a short stop in Paris. It was an unforgettable tour. Kogan played in Buenos Aires in the old South American Cordoba, performed the works of Brahms, Bach’s Chaconne, Millau’s Brazilian Dances, and the play Cueca by the Argentine composer Aguirre. In Uruguay, he introduced the listeners to Khachaturian’s Concerto, played for the first time on the South American continent. In Chile, he met with the poet Pablo Neruda, and in the hotel restaurant where he and Mytnik stayed, he heard the amazing play of the famous guitarist Allan. Having recognized the Soviet artists, Allan performed for them the first part of Beethoven’s Moonlight Sonata, pieces by Granados and Albeniz. He was visiting Lolita Torres. On the way back, in Paris, he attended the anniversary of Marguerite Long. At his concert among the audience were Arthur Rubinstein, cellist Charles Fournier, violinist and music critic Helene Jourdan-Morrange and others.

During the 1957/58 season he toured North America. It was his US debut. At Carnegie Hall he performed the Brahms Concerto, conducted by Pierre Monte. “He was clearly nervous, as any artist performing for the first time in New York should be,” Howard Taubman wrote in The New York Times. – But as soon as the first blow of the bow on the strings sounded, it became clear to everyone – we have a finished master in front of us. Kogan’s magnificent technique knows no difficulty. In the highest and most difficult positions, his sound remains clear and completely obeys any musical intentions of the artist. His concept of the Concerto is broad and slender. The first part was played with brilliance and depth, the second sang with unforgettable expressiveness, the third swept in a jubilant dance.

“I have never listened to a violinist who does so little to impress the audience and so much to convey the music they play. He only has his characteristic, unusually poetic, refined musical temperament, ”wrote Alfred Frankenstein. The Americans noted the artist’s modesty, the warmth and humanity of his playing, the absence of anything ostentatious, the amazing freedom of technique and the completeness of phrasing. The triumph was complete.

It is significant that American critics drew attention to the artist’s democratism, his simplicity, modesty, and in the game – to the absence of any elements of aesthetics. And this is Kogan deliberately. In his statements, a lot of space is given to the relationship between the artist and the public, he believes that while listening to its artistic needs as much as possible, one must at the same time carry one into the realm of serious music, by the power of performing conviction. His temperament, combined with will, helps to achieve such a result.

When, after the United States of America, he performed in Japan (1958), they wrote about him: “In the performance of Kogan, the heavenly music of Beethoven, Brahms became earthly, alive, tangible.” Instead of fifteen concerts, he gave seventeen. His arrival was rated as the biggest event of the musical season.

In 1960, the opening of the Exhibition of Soviet Science, Technology and Culture took place in Havana, the capital of Cuba. Kogan and his wife Lisa Gilels and composer A. Khachaturian came to visit the Cubans, from whose works the program of the gala concert was compiled. Temperamental Cubans almost smashed the hall with delight. From Havana, the artists went to Bogota, the capital of Colombia. As a result of their visit, the Columbia-USSR society was organized there. Then followed Venezuela and on the way back to their homeland – Paris.

Of Kogan’s subsequent tours, trips to New Zealand stand out, where he gave concerts with Lisa Gilels for two months and a second tour of America in 1965.

New Zealand wrote: “There is no doubt that Leonid Kogan is the greatest violinist who has ever visited our country.” He is put on a par with Menuhin, Oistrakh. The joint performances of Kogan with Gilels also cause delight.

An amusing incident occurred in New Zealand, humorously described by the Sun newspaper. A football team stayed at the same hotel with Kogan. Preparing for the concert, Kogan worked all evening. By 23 p.m., one of the players, who were about to go to bed, angrily said to the receptionist: “Tell the violinist who lives at the end of the corridor to stop playing.”

“Sir,” the porter replied indignantly, “that’s how you talk about one of the world’s greatest violinists!”

Not having achieved the execution of their request from the porter, the players went to Kogan. The deputy captain of the team was not aware that Kogan did not speak English and addressed him in the following “purely Australian terms”:

– Hey, brother, won’t you stop playing with your balalaika? Come on, finally, wrap up and let us sleep.

Understanding nothing and believing that he was dealing with another music lover who asked to play something specially for him, Kogan “graciously responded to the request to“ round off ”by performing first a brilliant cadenza, and then a cheerful Mozart piece. The football team retreated in disarray.”

Kogan’s interest in Soviet music is significant. He constantly plays concertos by Shostakovich and Khachaturian. T. Khrennikov, M. Weinberg, concert “Rhapsody” by A. Khachaturian, Sonata by A. Nikolaev, “Aria” by G. Galynin dedicated their concerts to him.

Kogan has performed with the world’s greatest musicians — conductors Pierre Monte, Charles Munsch, Charles Bruck, pianists Emil Gilels, Arthur Rubinstein, and others. “I really like to play with Arthur Rubinstein,” says Kogan. “It brings great joy every time. In New York, I had the good fortune to play two of Brahms’ sonatas and Beethoven’s Eighth Sonata with him on New Year’s Eve. I was struck by the sense of ensemble and rhythm of this artist, his ability to instantly penetrate the essence of the author’s intention … “

Kogan also shows himself as a talented teacher, professor at the Moscow Conservatory. The following grew up in Kogan’s class: the Japanese violinist Ekko Sato, who won the title of laureate of the III International Tchaikovsky Competition in Moscow in 1966; Yugoslav violinists A. Stajic, V. Shkerlak and others. Like Oistrakh’s class, Kogan’s class attracted students from different countries.

People’s Artist of the USSR Kogan in 1965 was awarded the high title of laureate of the Lenin Prize.

I would like to finish the essay about this wonderful musician-artist with the words of D. Shostakovich: “You feel a deep gratitude to him for the pleasure that you experience when you enter the wonderful, bright world of music together with the violinist.”

L. Raaben, 1967

In the 1960s-1970s, Kogan received all possible titles and awards. He is awarded the title of Professor and People’s Artist of the RSFSR and the USSR, and the Lenin Prize. In 1969, the musician was appointed head of the violin department of the Moscow Conservatory. Several films are made about the violinist.

The last two years of the life of Leonid Borisovich Kogan were especially eventful performances. He complained that he did not have time to rest.

In 1982, the premiere of Kogan’s last work, The Four Seasons by A. Vivaldi, took place. In the same year, the maestro heads the jury of violinists at the VII International P.I. Tchaikovsky. He participates in the filming of a film about Paganini. Kogan is elected Honorary Academician of the Italian National Academy “Santa Cecilia”. He tours in Czechoslovakia, Italy, Yugoslavia, Greece, France.

On December 11-15, the last concerts of the violinist took place in Vienna, where he performed the Beethoven Concerto. On December 17, Leonid Borisovich Kogan died suddenly on the way from Moscow to concerts in Yaroslavl.

The master left many students – laureates of all-Union and international competitions, famous performers and teachers: V. Zhuk, N. Yashvili, S. Kravchenko, A. Korsakov, E. Tatevosyan, I. Medvedev, I. Kaler and others. Foreign violinists studied with Kogan: E. Sato, M. Fujikawa, I. Flory, A. Shestakova.