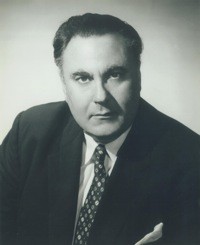

Karl Ilyich Eliasberg |

Karl Eliasberg

August 9, 1942. On everyone’s lips – “Leningrad – blockade – Shostakovich – 7th symphony – Eliasberg”. Then world fame came to Karl Ilyich. Almost 65 years have passed since that concert, and almost thirty years have passed since the death of the conductor. What is the figure of Eliasberg seen today?

In the eyes of his contemporaries, Eliasberg was one of the leaders of his generation. His distinguishing features were a rare musical talent, “impossible” (by Kurt Sanderling’s definition) hearing, honesty and integrity “regardless of faces”, purposefulness and diligence, encyclopedic education, accuracy and punctuality in everything, the presence of his rehearsal method developed over the years. (Here Yevgeny Svetlanov is remembered: “In Moscow, there was a constant litigation between our orchestras for Karl Ilyich. Everyone wanted to get him. Everyone wanted to work with him. The benefits of his work were enormous.”) In addition, Eliasberg was known as an excellent accompanist , and stood out among his contemporaries by performing the music of Taneyev, Scriabin and Glazunov, and along with them J.S. Bach, Mozart, Brahms and Bruckner.

What goal did this musician, so valued by his contemporaries, set for himself, what idea did he serve until the last days of his life? Here we come to one of the main qualities of Eliasberg as a conductor.

Kurt Sanderling, in his memoirs of Eliasberg, said: “The work of an orchestra player is difficult.” Yes, Karl Ilyich understood this, but continued to “press” on the teams entrusted to him. And it’s not even that he physically could not bear the falsity or the approximate execution of the author’s text. Eliasberg was the first Russian conductor to realize that “you can’t go far in the carriage of the past.” Even before the war, the best European and American orchestras reached qualitatively new performing positions, and the young Russian orchestra guild should not (even in the absence of a material and instrumental base) trail behind world conquests.

In the post-war years, Eliasberg toured a lot – from the Baltic states to the Far East. He had forty-five orchestras in his practice. He studied them, knew their strengths and weaknesses, often arriving in advance to listen to the band before his rehearsals (in order to better prepare for work, to have time to make adjustments to the rehearsal plan and orchestral parts). Eliasberg’s gift for analysis helped him find elegant and efficient ways of working with orchestras. Here is just one observation made on the basis of the study of Eliasberg’s symphonic programs. It becomes obvious that he often performed Haydn’s symphonies with all orchestras, not simply because he loved this music, but because he used it as a methodological system.

Russian orchestras born after 1917 missed in their education the simple basic elements that are natural for the European symphony school. The “Haydn Orchestra”, on which European symphonism grew, in the hands of Eliasberg was an instrument necessary to fill this gap in the domestic symphony school. Just? Obviously, but it had to be understood and put into practice, as Eliasberg did. And this is just one example. Today, comparing the recordings of the best Russian orchestras of fifty years ago with the modern, much better playing of our orchestras “from small to great”, you understand that the selfless work of Eliasberg, who began his career almost alone, was not in vain. A natural process of transferring experience took place – contemporary orchestral musicians, having gone through the crucible of his rehearsals, “jumping above their heads” in his concerts, already as teachers raised the level of professional requirements for their pupils. And the next generation of orchestra players, of course, began to play cleaner, more precisely, became more flexible in ensembles.

In fairness, we note that Karl Ilyich could not have achieved the result alone. His first followers were K. Kondrashin, K. Zanderling, A. Stasevich. Then the post-war generation “connected” – K. Simeonov, A. Katz, R. Matsov, G. Rozhdestvensky, E. Svetlanov, Yu. Temirkanov, Yu. Nikolaevsky, V. Verbitsky and others. Many of them subsequently proudly called themselves students of Eliasberg.

It must be said that, to Eliasberg’s credit, while influencing others, he developed and improved himself. From a tough and “squeezing out the result” (according to the recollections of my teachers) conductor, he became a calm, patient, wise teacher – this is how we, the orchestra members of the 60s and 70s, remember him. Although his severity remained. At that time, such a style of communication between the conductor and the orchestra seemed to us for granted. And only later did we realize how lucky we were at the very beginning of our career.

In the modern dictionary, the epithets “star”, “genius”, “man-legend” are commonplace, having long lost their original meaning. The intelligentsia of Eliasberg’s generation was disgusted by verbal chatter. But in relation to Eliasberg, the use of the epithet “legendary” never seemed pretentious. The bearer of this “explosive fame” himself was embarrassed by it, not considering himself somehow better than others, and in his stories about the siege, the orchestra and other characters of that time were the main characters.

Victor Kozlov