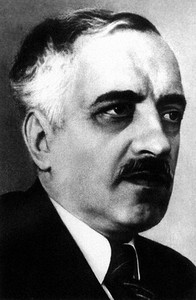

Ferruccio Busoni |

Ferruccio Busoni

Busoni is one of the giants of the world history of pianism, an artist of bright personality and broad creative aspirations. The musician combined the features of the “last Mohicans” of the art of the XNUMXth century and a bold visionary of the future ways of developing artistic culture.

Ferruccio Benvenuto Busoni was born on April 1, 1866 in northern Italy, in the Tuscan region in the town of Empoli. He was the only son of Italian clarinetist Ferdinando Busoni and pianist Anna Weiss, an Italian mother and a German father. The boy’s parents were engaged in concert activities and led a wandering life, which the child had to share.

The father was the first and very picky teacher of the future virtuoso. “My father understood little in the piano playing and, in addition, was unsteady in rhythm, but compensated for these shortcomings with completely indescribable energy, rigor and pedantry. He was able to sit next to me for four hours a day, controlling every note and every finger. At the same time, there could be no question of any indulgence, rest, or the slightest inattention on his part. The only pauses were caused by explosions of his unusually irascible temperament, followed by reproaches, dark prophecies, threats, slaps and copious tears.

All this ended with repentance, fatherly consolation and assurance that only good things were wanted for me, and the next day it all started anew. Orienting Ferruccio to the Mozartian path, his father forced the seven-year-old boy to start public performances. It happened in 1873 in Trieste. On February 8, 1876, Ferruccio gave his first independent concert in Vienna.

Five days later, a detailed review by Eduard Hanslick appeared in the Neue Freie Presse. The Austrian critic noted the “brilliant success” and “extraordinary abilities” of the boy, distinguishing him from the crowd of those “miracle children” “for whom the miracle ends with childhood.” “For a long time,” the reviewer wrote, “no child prodigy aroused such sympathy in me as little Ferruccio Busoni. And precisely because there is so little of a child prodigy in him and, on the contrary, a lot of a good musician … He plays fresh, naturally, with that hard-to-define, but immediately obvious musical instinct, thanks to which the right tempo, the right accents are everywhere, the spirit of rhythm is grasped , voices are clearly distinguished in polyphonic episodes … “

The critic also noted the “surprisingly serious and courageous character” of the concerto’s composing experiments, which, together with his predilection for “life-filled figurations and small combinational tricks,” testified to “a loving study of Bach”; the free fantasy, which Ferruccio improvised beyond the program, “predominantly in an imitative or contrapuntal spirit” was distinguished by the same features, on topics immediately proposed by the author of the review.

After studying with W. Mayer-Remy, the young pianist began to tour extensively. In the fifteenth year of his life, he was elected to the famous Philharmonic Academy in Bologna. Having successfully passed the most difficult exam, in 1881 he became a member of the Bologna Academy – the first case after Mozart that this honorary title was awarded at such an early age.

At the same time, he wrote a lot, published articles in various newspapers and magazines.

By that time, Busoni had left his parental home and settled in Leipzig. It was not easy for him to live there. Here is one of his letters:

“… The food, not only in quality, but also in quantity, leaves much to be desired … My Bechstein arrived the other day, and the next morning I had to give my last taler to the porters. The night before, I was walking down the street and met Schwalm (owner of the publishing house – author), whom I immediately stopped: “Take my writings – I need money.” “I can’t do this now, but if you agree to write a little fantasy for me on The Barber of Baghdad, then come to me in the morning, I will give you fifty marks in advance and a hundred marks after the work is ready.” – “Deal!” And we said goodbye.”

In Leipzig, Tchaikovsky showed interest in his activities, predicting a great future for his 22-year-old colleague.

In 1889, having moved to Helsingfors, Busoni met the daughter of a Swedish sculptor, Gerda Shestrand. A year later, she became his wife.

A significant milestone in the life of Busoni was 1890, when he took part in the First International Competition of Pianists and Composers named after Rubinstein. One prize was awarded in each section. And the composer Busoni managed to win her. It is all the more paradoxical that the prize among pianists was awarded to N. Dubasov, whose name was later lost in the general stream of performers … Despite this, Busoni soon became a professor at the Moscow Conservatory, where he was recommended by Anton Rubinstein himself.

Unfortunately, the director of the Moscow Conservatory V. I. Safonov disliked the Italian musician. This forced Busoni to move to the United States in 1891. It was there that a turning point took place in him, the result of which was the birth of a new Busoni – a great artist who amazed the world and made up an era in the history of pianistic art.

As AD Alekseev writes: “Busoni’s pianism has undergone a significant evolution. At first, the young virtuoso’s playing style had the character of academicized romantic art, correct, but nothing particularly remarkable. In the first half of the 1890s, Busoni dramatically changed his aesthetic positions. He becomes an artist-rebel, who defied decayed traditions, an advocate of a decisive renewal of art … “

The first major success came to Busoni in 1898, after his Berlin Cycle, dedicated to “the historical development of the piano concerto”. After the performance in musical circles, they started talking about a new star that had risen in the pianistic firmament. Since that time, Busoni’s concert activity has acquired a huge scope.

The fame of the pianist was multiplied and approved by numerous concert trips to various cities in Germany, Italy, France, England, Canada, the USA and other countries. In 1912 and 1913, after a long break, Busoni reappeared on the stages of St. Petersburg and Moscow, where his concerts gave rise to the famous “war” between busonists and Hoffmannists.

“If in Hoffmann’s performance I was amazed by the subtlety of musical drawing, technical transparency and accuracy of following the text,” writes M. N. Barinova, “in Busoni’s performance I felt an affinity for fine art. In his performance, the first, second, third plans were clear, to the thinnest line of the horizon and the haze that hid the contours. The most varied shades of the piano were, as it were, depressions, along with which all the shades of the forte seemed to be reliefs. It was in this sculptural plan that Busoni performed “Sposalizio”, “II penseroso” and “Canzonetta del Salvator Rosa” from Liszt’s second “Year of Wanderings”.

“Sposalizio” sounded in solemn calm, recreating in front of the audience an inspired picture of Raphael. The octaves in this work performed by Busoni were not of a virtuoso nature. A thin web of polyphonic fabric was brought to the finest, velvety pianissimo. Large, contrasting episodes did not interrupt the unity of thought for a second.

These were the last meetings of the Russian audience with the great artist. Soon the First World War began, and Busoni did not come to Russia again.

The energy of this man simply had no limits. At the beginning of the century, among other things, he organized “orchestral evenings” in Berlin, in which many new and rarely performed works by Rimsky-Korsakov, Franck, Saint-Saens, Fauré, Debussy, Sibelius, Bartok, Nielsen, Sindinga, Isai…

He paid a lot of attention to composition. The list of his works is very large and includes works of different genres.

Talented youth grouped around the famous maestro. In different cities, he taught piano lessons and taught at conservatories. Dozens of first-class performers studied with him, including E. Petri, M. Zadora, I. Turchinsky, D. Tagliapetra, G. Beklemishev, L. Grunberg and others.

Busoni’s numerous literary works devoted to music and his favorite instrument, the piano, have not lost their value.

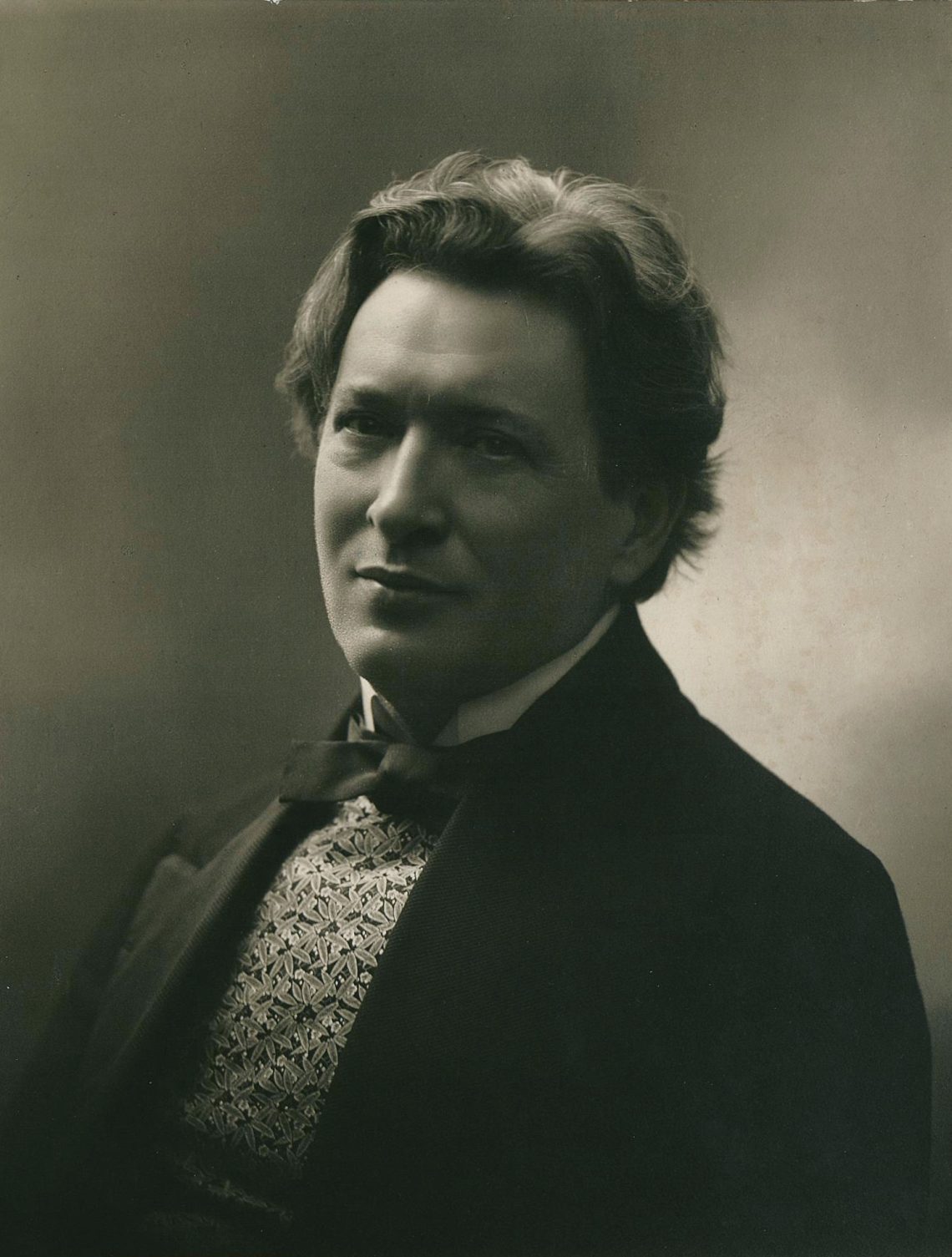

However, at the same time, Busoni wrote the most significant page in the history of world pianism. At the same time, Eugene d’Albert’s bright talent shone on concert stages with him. Comparing these two musicians, the outstanding German pianist W. Kempf wrote: “Of course, there were more than one arrow in d’Albert’s quiver: this great piano magician also quenched his passion for the dramatic in the field of opera. But, comparing him with the figure of the Italo-German Busoni, commensurate the total value of both, I tip the scales in favor of Busoni, an artist who is completely beyond comparison. D’Albert at the piano gave the impression of an elemental force that fell like lightning, accompanied by a monstrous clap of thunder, on the heads of listeners dumbfounded with surprise. Busoni was completely different. He was also a piano wizard. But he was not satisfied with the fact that, thanks to his incomparable ear, phenomenal infallibility of technique and vast knowledge, he left his mark on the works he performed. Both as a pianist and as a composer, he was most attracted by the still untrodden paths, their supposed existence attracted him so much that, succumbing to his nostalgia, he set off in search of new lands. While d’Albert, the true son of nature, was not aware of any problems whatsoever, with that other ingenious “translator” of masterpieces (a translator, by the way, into a very sometimes difficult language), from the very first bars you felt yourself transferred to the world of ideas of highly spiritual origin. It is understandable, therefore, that the superficially perceiving – the most numerous, no doubt – part of the public admired only the absolute perfection of the master’s technique. Where this technique did not manifest itself, the artist reigned in magnificent solitude, shrouded in pure, transparent air, like a distant god, on whom the languor, desires and suffering of people cannot have any effect.

More an artist – in the truest sense of the word – than all the other artists of his time, it was not by chance that he took up the problem of Faust in his own way. Didn’t he himself sometimes give the impression of a certain Faust, transferred with the help of a magic formula from his study to the stage, and, moreover, not aging Faust, but in all the splendor of his manly beauty? For since the time of Liszt – the greatest peak – who else could compete at the piano with this artist? His face, his delightful profile, bore the stamp of the extraordinary. Truly, the combination of Italy and Germany, which has so often been attempted to be carried out with the help of external and violent means, found in it, by the grace of the gods, its living expression.

Alekseev notes the talent of Busoni as an improviser: “Busoni defended the creative freedom of the interpreter, believed that the notation was intended only to “fix improvisation” and that the performer should free himself from the “fossil of signs”, “set them in motion”. In his concert practice, he often changed the text of compositions, played them essentially in his own version.

Busoni was an exceptional virtuoso who continued and developed the traditions of Liszt’s virtuoso coloristic pianism. Possessing equally all kinds of piano technique, he amazed the listeners with the brilliance of performance, chased finish and the energy of sounding finger passages, double notes and octaves at the fastest pace. Particularly attracted attention was the extraordinary brilliance of his sound palette, which seemed to absorb the richest timbres of a symphony orchestra and organ … “

M. N. Barinova, who visited the great pianist at home in Berlin shortly before the First World War, recalls: “Busoni was an extremely versatile educated person. He knew literature very well, was both a musicologist and a linguist, a connoisseur of fine arts, a historian and a philosopher. I remember how some Spanish linguists once came to him to resolve their dispute about the peculiarities of one of the Spanish dialects. His erudition was colossal. One had only to wonder where he took the time to replenish his knowledge.

Ferruccio Busoni died on July 27, 1924.