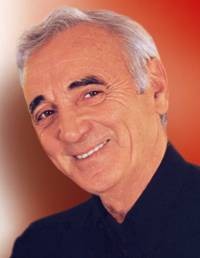

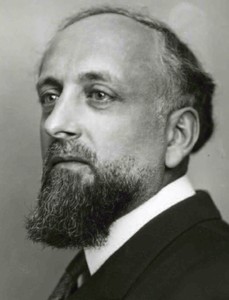

Ernest Ansermet |

Ernest Ansermet

The peculiar and majestic figure of the Swiss conductor marks a whole era in the development of modern music. In 1928, the German magazine Di Muzik wrote in an article devoted to Anserme: “Like few conductors, he belongs entirely to our time. Only on the basis of the multifaceted, contradictory picture of our life, one can comprehend his personality. To comprehend, but not to reduce to a single formula.

To tell about Anserme’s unusual creative path also means in many ways to tell the story of the musical life of his country, and above all the wonderful Orchestra of Romanesque Switzerland, founded by him in 1918.

By the time the orchestra was founded, Ernest Ansermet was 35 years old. From his youth, he was fond of music, spent long hours at the piano. But he did not receive a systematic musical, and even more so a conductor’s education. He studied at the gymnasium, in the cadet corps, at Lausanne College, where he studied mathematics. Later, Ansermet traveled to Paris, attended the conductor’s class at the conservatory, spent one winter in Berlin, listening to concerts of outstanding musicians. For a long time he was unable to fulfill his dream: the need to earn a living forced the young man to study mathematics. But all this time, Ansermet did not leave thoughts of becoming a musician. And when, it seemed, the prospects of a scientific career opened up before him, he gave up everything to take the modest place of bandmaster of a small resort orchestra in Montreux, which happened to be randomly turned up. Here in those years a fashionable audience gathered – representatives of high society, the rich, as well as artists. Among the listeners of the young conductor was somehow Igor Stravinsky. This meeting was decisive in the life of Ansermet. Soon, on the advice of Stravinsky, Diaghilev invited him to his place – to the Russian ballet troupe. Working here not only helped Anserme gain experience – during this time he got acquainted with Russian music, which he became a passionate admirer for life.

During the difficult war years, the artist’s career was interrupted for some time – instead of a conductor’s baton, he was again forced to pick up a teacher’s pointer. But already in 1918, having brought together the best Swiss musicians, Ansermet organized, in fact, the first professional orchestra in his country. Here, at the crossroads of Europe, at the crossroads of various influences and cultural currents, he began his independent activity.

The orchestra consisted of only eighty musicians. Now, half a century later, it is one of the best bands in Europe, numbering more than a hundred people and known everywhere thanks to its tours and recordings.

From the very beginning, Ansermet’s creative sympathies were clearly defined, reflected in the repertoire and artistic appearance of his team. First of all, of course, French music (especially Ravel and Debussy), in the transfer of the colorful palette of which Ansermet has few equals. Then the Russian classics, “Kuchkists”. Ansermet was the first to introduce his compatriots, and many listeners from other countries, to their work. And finally, contemporary music: Honegger and Milhaud, Hindemith and Prokofiev, Bartok and Berg, and above all, Stravinsky, one of the conductor’s favorite authors. Ansermet’s ability to ignite musicians and listeners, captivate them with the whimsical colors of Stravinsky’s music, reveal in all its brilliance the element of his early compositions – The Rite of Spring. “Petrushka”, “Firebird” – and still remains unsurpassed. As one of the critics noted, “the orchestra under the direction of Ansermet shines with dazzling colors, the whole lives, breathes deeply and captures the audience with its breath.” In this repertoire, the astonishing temperament of the conductor, the plasticity of his interpretation, manifested itself in all its brilliance. Ansermet shunned all sorts of cliches and standards – each of his interpretations was original, not like any sample. Perhaps, here, in a positive sense, Ansermet’s lack of a real school, his freedom from conductor’s traditions, had an effect. True, the interpretation of classical and romantic music, especially by German composers, as well as Tchaikovsky, was not Ansermet’s strong point: here his concepts turned out to be less convincing, often superficial, devoid of depth and scope.

A passionate propagandist of modern music, who gave a start to the life of many works, Ansermet, however, strongly opposed the destructive tendencies inherent in modern avant-garde movements.

Ansermet toured the USSR twice, in 1928 and 1937. The conductor’s skill in performing French music and Stravinsky’s works was duly appreciated by our listeners.

L. Grigoriev, J. Platek