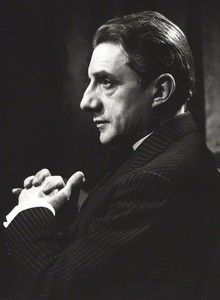

David Fedorovich Oistrakh |

David Oistrakh

The Soviet Union has long been famous for violinists. Back in the 30s, the brilliant victories of our performers at international competitions amazed the world musical community. The Soviet violin school was talked about as the best in the world. Among the constellation of brilliant talents, the palm already belonged to David Oistrakh. He has retained his position to this day.

Many articles have been written about Oistrakh, perhaps in the languages of most peoples of the world; monographs and essays have been written about him, and it seems that there are no words that would not be said about the artist by admirers of his wonderful talent. And yet I want to talk about it again and again. Perhaps, none of the violinists reflected so fully the history of the violin art of our country. Oistrakh developed along with the Soviet musical culture, deeply absorbing its ideals, its aesthetics. He was “created” as an artist by our world, carefully directing the development of the artist’s great talent.

There is art that suppresses, gives rise to anxiety, makes you experience life’s tragedies; but there is art of a different kind, which brings peace, joy, heals spiritual wounds, promotes the establishment of faith in life, in the future. The latter is highly characteristic of Oistrakh. Oistrakh’s art testifies to the amazing harmony of his nature, his spiritual world, to a bright and clear perception of life. Oistrakh is a searching artist, forever dissatisfied with what he has achieved. Each stage of his creative biography is a “new Oistrakh”. In the 30s, he was a master of miniatures, with an emphasis on soft, charming, light lyricism. At that time, his playing captivated with subtle grace, penetrating lyrical nuances, refined completeness of every detail. Years passed, and Oistrakh turned into a master of large, monumental forms, while maintaining his former qualities.

At the first stage, his game was dominated by “watercolor tones” with a bias towards an iridescent, silvery range of colors with imperceptible transitions from one to another. However, in the Khachaturian Concerto, he suddenly showed himself in a new capacity. He seemed to create an intoxicating colorful picture, with deep “velvety” timbres of sound color. And if in the concerts of Mendelssohn, Tchaikovsky, in the miniatures of Kreisler, Scriabin, Debussy, he was perceived as a performer of a purely lyrical talent, then in Khachaturian’s Concerto he appeared as a magnificent genre painter; his interpretation of this Concerto has become a classic.

A new stage, a new culmination of the creative development of an amazing artist – Shostakovich’s Concerto. It is impossible to forget the impression left by the premiere of the Concert performed by Oistrakh. He literally transformed; his game acquired a “symphonic” scale, tragic power, “wisdom of the heart” and pain for a person, which are so inherent in the music of the great Soviet composer.

Describing Oistrakh’s performance, it is impossible not to note his high instrumental skill. It seems that nature has never created such a complete fusion of man and instrument. At the same time, the virtuosity of Oistrakh’s performance is special. It has both brilliance and showiness when music requires it, but they are not the main thing, but plasticity. The amazing lightness and ease with which the artist performs the most puzzling passages is unparalleled. The perfection of his performing apparatus is such that you get true aesthetic pleasure when you watch him play. With incomprehensible dexterity, the left hand moves along the neck. There are no sharp jolts or angular transitions. Any jump is overcome with absolute freedom, any stretching of the fingers – with the utmost elasticity. The bow is “linked” to the strings in such a way that the quivering, caressing timbre of Oistrakh’s violin will not soon be forgotten.

Years add more and more facets to his art. It becomes deeper and… easier. But, evolving, constantly moving forward, Oistrakh remains “himself” – an artist of light and sun, the most lyrical violinist of our time.

Oistrakh was born in Odessa on September 30, 1908. His father, a modest office worker, played the mandolin, violin, and was a great lover of music; mother, a professional singer, sang in the choir of the Odessa Opera House. From the age of four, little David listened with enthusiasm to operas in which his mother sang, and at home he played performances and “conducted” an imaginary orchestra. His musicality was so obvious that he became interested in a well-known teacher who became famous in his work with children, the violinist P. Stolyarsky. From the age of five, Oistrakh began to study with him.

The First World War broke out. Oistrakh’s father went to the front, but Stolyarsky continued to work with the boy free of charge. At that time, he had a private music school, which in Odessa was called a “talent factory”. “He had a big, ardent soul as an artist and an extraordinary love for children,” recalls Oistrakh. Stolyarsky instilled in him a love for chamber music, forced him to play music in school ensembles on the viola or violin.

After the revolution and the civil war, the Music and Drama Institute was opened in Odessa. In 1923, Oistrakh entered here, and, of course, in the class of Stolyarsky. In 1924 he gave his first solo concert and quickly mastered the central works of the violin repertoire (concerts by Bach, Tchaikovsky, Glazunov). In 1925 he made his first concert trip to Elizavetgrad, Nikolaev, Kherson. In the spring of 1926, Oistrakh graduated from the institute with brilliance, having performed Prokofiev’s First Concerto, Tartini’s Sonata “Devil’s Trills”, A. Rubinstein’s Sonata for Viola and Piano.

Let us note that Prokofiev’s Concerto was chosen as the main examination work. At that time, not everyone could take such a bold step. Prokofiev’s music was perceived by a few, it was with difficulty that it won recognition from musicians brought up on the classics of the XNUMXth-XNUMXth centuries. The desire for novelty, quick and deep comprehension of the new remained characteristic of Oistrakh, whose performance evolution can be used to write the history of Soviet violin music. It can be said without exaggeration that most of the violin concertos, sonatas, works of large and small forms created by Soviet composers were first performed by Oistrakh. Yes, and from the foreign violin literature of the XNUMXth century, it was Oistrakh who introduced Soviet listeners to many major phenomena; for example, with concertos by Szymanowski, Chausson, Bartók’s First Concerto, etc.

Of course, at the time of his youth, Oistrakh could not understand the music of the Prokofiev concerto deeply enough, as the artist himself recalls. Shortly after Oistrakh graduated from the institute, Prokofiev came to Odessa with author’s concerts. At an evening organized in his honor, the 18-year-old Oistrakh performed the scherzo from the First Concerto. The composer was sitting near the stage. “During my performance,” recalls Oistrakh, “his face became more and more gloomy. When the applause broke out, he did not take part in them. Approaching the stage, ignoring the noise and excitement of the audience, he asked the pianist to give way to him and, turning to me with the words: “Young man, you don’t play at all the way you should,” he began to show and explain to me the nature of his music. . Many years later, Oistrakh reminded Prokofiev of this incident, and he was visibly embarrassed when he found out who the “unfortunate young man” who had suffered so much from him was.

In the 20s, F. Kreisler had a great influence on Oistrakh. Oistrakh became acquainted with his performance through recordings and was captivated by the originality of his style. Kreisler’s enormous impact on the generation of violinists of the 20s and 30s is usually seen as both positive and negative. Apparently, Kreisler was “guilty” of Oistrakh’s fascination with a small form – miniatures and transcriptions, in which Kreisler’s arrangements and original plays occupied a significant place.

Passion for Kreisler was universal and few remained indifferent to his style and creativity. From Kreisler, Oistrakh adopted some playing techniques – characteristic glissando, vibrato, portamento. Perhaps Oistrakh is indebted to the “Kreisler school” for the elegance, ease, softness, richness of “chamber” shades that captivate us in his game. However, everything that he borrowed was unusually organically processed by him even at that time. The individuality of the young artist turned out to be so bright that it transformed any “acquisition”. In his mature period, Oistrakh left Kreisler, putting the expressive techniques that he had once adopted from him into the service of completely different goals. The desire for psychologism, the reproduction of a complex world of deep emotions led him to the methods of declamatory intonation, the nature of which is directly opposite to the elegant, stylized lyrics of Kreisler.

In the summer of 1927, on the initiative of the Kyiv pianist K. Mikhailov, Oistrakh was introduced to A. K. Glazunov, who had come to Kyiv to conduct several concerts. In the hotel where Oistrakh was brought, Glazunov accompanied the young violinist in his Concerto on the piano. Under the baton of Glazunov, Oistrakh twice performed the Concerto in public with the orchestra. In Odessa, where Oistrakh returned with Glazunov, he met Polyakin, who was touring there, and after a while, with the conductor N. Malko, who invited him on his first trip to Leningrad. On October 10, 1928, Oistrakh made a successful debut in Leningrad; the young artist gained popularity.

In 1928 Oistrakh moved to Moscow. For some time he leads the life of a guest performer, traveling around Ukraine with concerts. Of great importance in his artistic activity was the victory at the All-Ukrainian Violin Competition in 1930. He won first prize.

P. Kogan, director of the concert bureau of state orchestras and ensembles of Ukraine, became interested in the young musician. An excellent organizer, he was a remarkable figure of the “Soviet impresario-educator”, as he can be called according to the direction and nature of his activity. He was a real propagandist of classical art among the masses, and many Soviet musicians keep a good memory of him. Kogan did a lot to popularize Oistrakh, but still the violinist’s main area of concerts was outside Moscow and Leningrad. Only by 1933 did Oistrakh begin to make his way in Moscow as well. His performance with a program composed of concertos by Mozart, Mendelssohn and Tchaikovsky, performed in one evening, was an event about which musical Moscow spoke. Reviews are written about Oistrakh, in which it is noted that his playing carries the best qualities of the young generation of Soviet performers, that this art is healthy, intelligible, cheerful, strong-willed. Critics aptly notice the main features of his performing style, which were characteristic of him in those years – exceptional skill in the performance of works of small form.

At the same time, in one of the articles we find the following lines: “However, it is premature to consider that the miniature is his genre. No, Oistrakh’s sphere is music of plastic, graceful forms, full-blooded, optimistic music.

In 1934, on the initiative of A. Goldenweiser, Oistrakh was invited to the conservatory. This is where his teaching career began, which continues to the present.

The 30s were the time of Oistrakh’s brilliant triumphs on the all-Union and world stage. 1935 – first prize at the II All-Union Competition of Performing Musicians in Leningrad; in the same year, a few months later – the second prize at the Henryk Wieniawski International Violin Competition in Warsaw (the first prize went to Ginette Neve, Thibaut’s student); 1937 – first prize at the Eugene Ysaye International Violin Competition in Brussels.

The last competition, in which six of the seven first prizes were won by Soviet violinists D. Oistrakh, B. Goldstein, E. Gilels, M. Kozolupova and M. Fikhtengolts, was assessed by the world press as a triumph of the Soviet violin school. Competition jury member Jacques Thibault wrote: “These are wonderful talents. The USSR is the only country that has taken care of its young artists and provided full opportunities for their development. From today, Oistrakh is gaining worldwide fame. They want to listen to him in all countries.”

After the competition, its participants performed in Paris. The competition opened the way for Oistrakh to broad international activities. At home, Oistrakh becomes the most popular violinist, successfully competing in this respect with Miron Polyakin. But the main thing is that his charming art attracts the attention of composers, stimulating their creativity. In 1939, the Myaskovsky Concerto was created, in 1940 – Khachaturian. Both concerts are dedicated to Oistrakh. The performance of concertos by Myaskovsky and Khachaturian was perceived as a major event in the musical life of the country, was the result and culmination of the pre-war period of the remarkable artist’s activity.

During the war, Oistrakh continuously gave concerts, playing in hospitals, in the rear and at the front. Like most Soviet artists, he is full of patriotic enthusiasm, in 1942 he performs in besieged Leningrad. Soldiers and workers, sailors and residents of the city listen to him. “The Oki came here after a hard day’s work to listen to Oistrakh, an artist from the Mainland, from Moscow. The concert was not yet over when the air raid alert was announced. Nobody left the room. After the end of the concert, the artist was warmly welcomed. The ovation especially intensified when the decree on awarding the State Prize to D. Oistrakh was announced … ”.

The war is over. In 1945, Yehudi Menuhin arrived in Moscow. Oistrakh plays a double Bach Concerto with him. In the 1946/47 season he performed in Moscow a grandiose cycle dedicated to the history of the violin concerto. This act is reminiscent of the famous historical concerts of A. Rubinstein. The cycle included works such as concertos by Elgar, Sibelius and Walton. He defined something new in Oistrakh’s creative image, which has since become his inalienable quality – universalism, the desire for a wide coverage of violin literature of all times and peoples, including modernity.

After the war, Oistrakh opened up prospects for extensive international activity. His first trip took place in Vienna in 1945. The review of his performance is noteworthy: “… Only the spiritual maturity of his always stylish playing makes him a herald of high humanity, a truly significant musician, whose place is in the first rank of violinists of the world.”

In 1945-1947, Oistrakh met with Enescu in Bucharest, and with Menuhin in Prague; in 1951 he was appointed a member of the jury of the Belgian Queen Elisabeth International Competition in Brussels. In the 50s, the entire foreign press rated him as one of the world’s greatest violinists. While in Brussels, he performs with Thibault, who conducts the orchestra in his concerto, playing concertos by Bach, Mozart and Beethoven. Thiebaud is full of deep admiration for Oistrakh’s talent. Reviews of his performance in Düsseldorf in 1954 emphasize the penetrating humanity and spirituality of his performance. “This man loves people, this artist loves the beautiful, the noble; to help people experience this is his profession.”

In these reviews, Oistrakh appears as a performer reaching the depths of the humanistic principle in music. The emotionality and lyricism of his art are psychological, and this is what affects the listeners. “How to summarize the impressions of the game of David Oistrakh? – wrote E. Jourdan-Morrange. – Common definitions, however dithyrambic they may be, are unworthy of his pure art. Oistrakh is the most perfect violinist I have ever heard, not only in terms of his technique, which is equal to that of Heifetz, but especially because this technique is completely turned to the service of music. What honesty, what nobility in execution!

In 1955 Oistrakh went to Japan and the United States. In Japan, they wrote: “The audience in this country knows how to appreciate art, but is prone to restraint in the manifestation of feelings. Here, she literally went crazy. Stunning applause merged with shouts of “bravo!” and seemed to be able to stun. Oistrakh’s success in the USA bordered on triumph: “David Oistrakh is a great violinist, one of the truly great violinists of our time. Oistrakh is great not only because he is a virtuoso, but a genuine spiritual musician.” F. Kreisler, C. Francescatti, M. Elman, I. Stern, N. Milstein, T. Spivakovsky, P. Robson, E. Schwarzkopf, P. Monte listened to Oistrakh at the concert at Carnegie Hall.

“I was especially moved by the presence of Kreisler in the hall. When I saw the great violinist, listening intently to my playing, and then applauding me standing, everything that happened seemed like some kind of wonderful dream. Oistrakh met Kreisler during his second visit to the United States in 1962-1963. Kreisler was at that time already a very old man. Among the meetings with great musicians, one should also mention the meeting with P. Casals in 1961, which left a deep mark in the heart of Oistrakh.

The brightest line in Oistrakh’s performance is chamber-ensemble music. Oistrakh took part in chamber evenings in Odessa; later he played in a trio with Igumnov and Knushevitsky, replacing the violinist Kalinovsky in this ensemble. In 1935 he formed a sonata ensemble with L. Oborin. According to Oistrakh, it happened like this: they went to Turkey in the early 30s, and there they had to play a sonata evening. Their “sense of music” turned out to be so related that the idea came to continue this random association.

Numerous performances at joint evenings brought one of the greatest Soviet cellists, Svyatoslav Knushevitsky, closer to Oistrakh and Oborin. The decision to create a permanent trio came in 1940. The first performance of this remarkable ensemble took place in 1941, but a systematic concert activity began in 1943. The trio L. Oborin, D. Oistrakh, S. Knushevitsky for many years (until 1962, when Knushevitsky died) was the pride of Soviet chamber music. Numerous concerts of this ensemble invariably gathered full halls of an enthusiastic audience. His performances were held in Moscow, Leningrad. In 1952, the trio traveled to the Beethoven celebrations in Leipzig. Oborin and Oistrakh performed the entire cycle of Beethoven’s sonatas.

The game of the trio was distinguished by a rare coherence. The remarkable dense cantilena of Knushevitsky, with its sound, velvety timbre, perfectly combined with the silvery sound of Oistrakh. Their sound was complemented by singing on the piano Oborin. In music, the artists revealed and emphasized its lyrical side, their playing was distinguished by sincerity, softness coming from the heart. In general, the performing style of the ensemble can be called lyrical, but with classical poise and rigor.

The Oborin-Oistrakh Ensemble still exists today. Their sonata evenings leave an impression of stylistic integrity and completeness. The poetry inherent in Oborin’s play is combined with the characteristic logic of musical thinking; Oistrakh is an excellent partner in this regard. This is an ensemble of exquisite taste, rare musical intelligence.

Oistrakh is known all over the world. He is marked by many titles; in 1959 the Royal Academy of Music in London elected him an honorary member, in 1960 he became an honorary academician of the St. Cecilia in Rome; in 1961 – a corresponding member of the German Academy of Arts in Berlin, as well as a member of the American Academy of Sciences and Arts in Boston. Oistrakh was awarded the Orders of Lenin and the Badge of Honor; he was awarded the title of People’s Artist of the USSR. In 1961 he was awarded the Lenin Prize, the first among Soviet performing musicians.

In Yampolsky’s book about Oistrakh, his character traits are concisely and briefly captured: indomitable energy, hard work, a sharp critical mind, able to notice everything that is characteristic. This is evident from Oistrakh’s judgments about the playing of outstanding musicians. He always knows how to point out the most essential, sketch an accurate portrait, give a subtle analysis of style, notice the typical in the appearance of a musician. His judgments can be trusted, as they are for the most part impartial.

Yampolsky also notes a sense of humor: “He appreciates and loves a well-aimed, sharp word, is able to laugh contagiously when telling a funny story or listening to a comic story. Like Heifetz, he can hilariously copy the playing of beginning violinists.” With the colossal energy that he spends every day, he is always smart, restrained. In everyday life he loves sports – in his younger years he played tennis; an excellent motorist, passionately fond of chess. In the 30s, his chess partner was S. Prokofiev. Before the war, Oistrakh had been chairman of the sports section of the Central House of Artists for a number of years and a first-class chess master.

On the stage, Oistrakh is free; he does not have the excitement that so overshadows the variety activity of a huge number of performing musicians. Let us remember how painfully worried Joachim, Auer, Thiebaud, Huberman, Polyakin, how much nervous energy they spent on each performance. Oistrakh loves the stage and, as he admits, only significant breaks in performances cause him excitement.

Oistrakh’s work goes beyond the scope of direct performing activities. He contributed a lot to violin literature as an editor; for example, his version (together with K. Mostras) of Tchaikovsky’s violin concerto is excellent, enriching and largely correcting Auer’s version. Let us also point to Oistrakh’s work on both Prokofiev’s violin sonatas. The violinists owe him the fact that the Second Sonata, originally written for flute and violin, was remade by Prokofiev for violin.

Oistrakh is constantly working on new works, being their first interpreter. The list of new works by Soviet composers, “released” by Oistrakh, is huge. To name just a few: sonatas by Prokofiev, concertos by Myaskovsky, Rakov, Khachaturian, Shostakovich. Oistrakh sometimes writes articles about the pieces he has played, and some musicologist may envy his analysis.

Magnificent, for example, are the analyzes of the Violin Concerto by Myaskovsky, and especially by Shostakovich.

Oistrakh is an outstanding teacher. Among his students are laureates of international competitions V. Klimov; his son, currently a prominent concert soloist I. Oistrakh, as well as O. Parkhomenko, V. Pikaizen, S. Snitkovetsky, J. Ter-Merkeryan, R. Fine, N. Beilina, O. Krysa. Many foreign violinists strive to get into Oistrakh’s class. The French M. Bussino and D. Arthur, the Turkish E. Erduran, the Australian violinist M. Beryl-Kimber, D. Bravnichar from Yugoslavia, the Bulgarian B. Lechev, the Romanians I. Voicu, S. Georgiou studied under him. Oistrakh loves pedagogy and works in the classroom with passion. His method is based mainly on his own performing experience. “The comments he makes about this or that method of performance are always concise and extremely valuable; in every word-advice, he shows a deep understanding of the nature of the instrument and the techniques of violin performance.

He attaches great importance to the direct demonstration on the instrument by the teacher of the piece that the student is studying. But only showing, in his opinion, is useful mainly during the period when the student analyzes the work, because further it can hamper the development of the student’s creative individuality.

Oistrakh skillfully develops the technical apparatus of his students. In most cases, his pets are distinguished by the freedom of possession of the instrument. At the same time, special attention to technology is by no means characteristic of Oistrakh the teacher. He is much more interested in the problems of musical and artistic education of his students.

In recent years, Oistrakh has taken an interest in conducting. His first performance as a conductor took place on February 17, 1962 in Moscow – he accompanied his son Igor, who performed the concertos of Bach, Beethoven and Brahms. “Oistrakh’s conducting style is simple and natural, just like his manner of playing the violin. He is calm, stingy with unnecessary movements. He does not suppress the orchestra with his conductor’s “power”, but provides the performing team with maximum creative freedom, relying on the artistic intuition of its members. The charm and authority of a great artist have an irresistible effect on the musicians.”

In 1966, Oistrakh turned 58 years old. However, he is full of active creative energy. His skill is still distinguished by freedom, absolute perfection. It was only enriched by the artistic experience of a long lived life, completely devoted to his beloved art.

L. Raaben, 1967