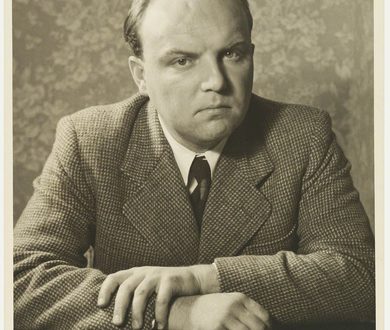

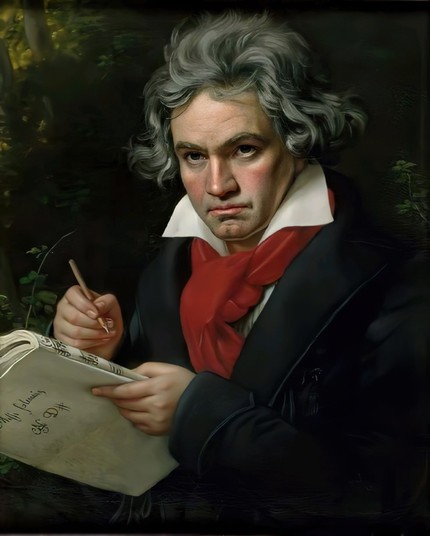

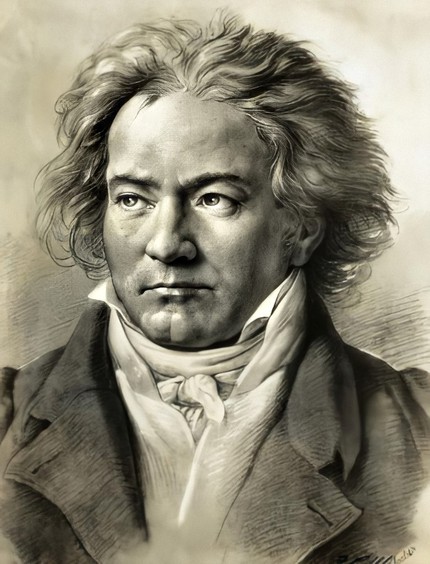

Ludwig van Beethoven |

Ludwig van Beethoven

My willingness to serve poor suffering humanity with my art has never, since my childhood… needed any reward other than inner satisfaction… L. Beethoven

Musical Europe was still full of rumors about the brilliant miracle child – W. A. Mozart, when Ludwig van Beethoven was born in Bonn, in the family of a tenorist of the court chapel. They christened him on December 17, 1770, naming him after his grandfather, a respected bandmaster, a native of Flanders. Beethoven received his first musical knowledge from his father and his colleagues. The father wanted him to become the “second Mozart”, and forced his son to practice even at night. Beethoven did not become a child prodigy, but he discovered his talent as a composer quite early. K. Nefe, who taught him composition and playing the organ, had a great influence on him – a man of advanced aesthetic and political convictions. Due to the poverty of the family, Beethoven was forced to enter the service very early: at the age of 13, he was enrolled in the chapel as an assistant organist; later worked as an accompanist at the Bonn National Theatre. In 1787 he visited Vienna and met his idol, Mozart, who, after listening to the young man’s improvisation, said: “Pay attention to him; he will someday make the world talk about him.” Beethoven failed to become a student of Mozart: a serious illness and the death of his mother forced him to hastily return to Bonn. There, Beethoven found moral support in the enlightened Breining family and became close to the university environment, which shared the most progressive views. The ideas of the French Revolution were enthusiastically received by Beethoven’s Bonn friends and had a strong influence on the formation of his democratic convictions.

In Bonn, Beethoven wrote a number of large and small works: 2 cantatas for soloists, choir and orchestra, 3 piano quartets, several piano sonatas (now called sonatinas). It should be noted that sonatas known to all novice pianists salt и F major to Beethoven, according to researchers, do not belong, but are only attributed, but another, truly Beethoven’s Sonatina in F major, discovered and published in 1909, remains, as it were, in the shadows and is not played by anyone. Most of the Bonn creativity is also made up of variations and songs intended for amateur music-making. Among them are the familiar song “Marmot”, the touching “Elegy on the Death of a Poodle”, the rebellious poster “Free Man”, the dreamy “Sigh of the unloved and happy love”, containing the prototype of the future theme of joy from the Ninth Symphony, “Sacrificial Song”, which Beethoven loved it so much that he returned to it 5 times (last edition – 1824). Despite the freshness and brightness of youthful compositions, Beethoven understood that he needed to study seriously.

In November 1792, he finally left Bonn and moved to Vienna, the largest musical center in Europe. Here he studied counterpoint and composition with J. Haydn, I. Schenck, I. Albrechtsberger and A. Salieri. Although the student was distinguished by obstinacy, he studied zealously and subsequently spoke with gratitude about all his teachers. At the same time, Beethoven began to perform as a pianist and soon gained fame as an unsurpassed improviser and the brightest virtuoso. In his first and last long tour (1796), he conquered the audience of Prague, Berlin, Dresden, Bratislava. The young virtuoso was patronized by many distinguished music lovers – K. Likhnovsky, F. Lobkowitz, F. Kinsky, the Russian ambassador A. Razumovsky and others, Beethoven’s sonatas, trios, quartets, and later even symphonies sounded for the first time in their salons. Their names can be found in the dedications of many of the composer’s works. However, Beethoven’s manner of dealing with his patrons was almost unheard of at the time. Proud and independent, he did not forgive anyone for attempts to humiliate his dignity. The legendary words thrown by the composer to the philanthropist who offended him are known: “There have been and will be thousands of princes, Beethoven is only one.” Of the numerous aristocratic students of Beethoven, Ertman, the sisters T. and J. Bruns, and M. Erdedy became his constant friends and promoters of his music. Not fond of teaching, Beethoven was nevertheless the teacher of K. Czerny and F. Ries in piano (both of them later won European fame) and the Archduke Rudolf of Austria in composition.

In the first Viennese decade, Beethoven wrote mainly piano and chamber music. In 1792-1802. 3 piano concertos and 2 dozen sonatas were created. Of these, only Sonata No. 8 (“Pathetic”) has an author’s title. Sonata No. 14, subtitled sonata-fantasy, was called “Lunar” by the romantic poet L. Relshtab. Stable names also strengthened behind sonatas No. 12 (“With a Funeral March”), No. 17 (“With Recitatives”) and later: No. 21 (“Aurora”) and No. 23 (“Appassionata”). In addition to piano, 9 (out of 10) violin sonatas belong to the first Viennese period (including No. 5 – “Spring”, No. 9 – “Kreutzer”; both names are also non-author’s); 2 cello sonatas, 6 string quartets, a number of ensembles for various instruments (including the cheerfully gallant Septet).

With the beginning of the XIX century. Beethoven also began as a symphonist: in 1800 he completed his First Symphony, and in 1802 his Second. At the same time, his only oratorio “Christ on the Mount of Olives” was written. The first signs of an incurable disease that appeared in 1797 – progressive deafness and the realization of the hopelessness of all attempts to treat the disease led Beethoven to a spiritual crisis in 1802, which was reflected in the famous document – the Heiligenstadt Testament. Creativity was the way out of the crisis: “… It was not enough for me to commit suicide,” the composer wrote. – “Only it, art, it kept me.”

1802-12 – the time of the brilliant flowering of the genius of Beethoven. The ideas of overcoming suffering by the strength of the spirit and the victory of light over darkness, deeply suffered by him, after a fierce struggle, turned out to be consonant with the main ideas of the French Revolution and the liberation movements of the early 23th century. These ideas were embodied in the Third (“Heroic”) and Fifth Symphonies, in the tyrannical opera “Fidelio”, in the music for the tragedy “Egmont” by J. W. Goethe, in the Sonata No. 21 (“Appassionata”). The composer was also inspired by the philosophical and ethical ideas of the Enlightenment, which he adopted in his youth. The world of nature appears full of dynamic harmony in the Sixth (“Pastoral”) Symphony, in the Violin Concerto, in the Piano (No. 10) and Violin (No. 7) Sonatas. Folk or close to folk melodies are heard in the Seventh Symphony and in quartets Nos. 9-8 (the so-called “Russian” – they are dedicated to A. Razumovsky; Quartet No. 2 contains XNUMX melodies of Russian folk songs: used much later also by N. Rimsky-Korsakov “Glory” and “Ah, is my talent, talent”). The Fourth Symphony is full of powerful optimism, the Eighth is permeated with humor and slightly ironic nostalgia for the times of Haydn and Mozart. The virtuoso genre is treated epicly and monumentally in the Fourth and Fifth Piano Concertos, as well as in the Triple Concerto for Violin, Cello and Piano and Orchestra. In all these works, the style of Viennese classicism found its most complete and final embodiment with its life-affirming faith in reason, goodness and justice, expressed at the conceptual level as a movement “through suffering to joy” (from Beethoven’s letter to M. Erdedy), and at the compositional level – as a balance between unity and diversity and the observance of strict proportions at the largest scale of the composition.

1812-15 – turning points in the political and spiritual life of Europe. The period of the Napoleonic wars and the rise of the liberation movement was followed by the Congress of Vienna (1814-15), after which reactionary-monarchist tendencies intensified in the domestic and foreign policy of European countries. The style of heroic classicism, expressing the spirit of the revolutionary renewal of the late 1813th century. and patriotic moods of the early 17th century, had to inevitably either turn into pompous semi-official art, or give way to romanticism, which became the leading trend in literature and managed to make itself known in music (F. Schubert). Beethoven also had to solve these complex spiritual problems. He paid tribute to the victorious jubilation, creating a spectacular symphonic fantasy “The Battle of Vittoria” and the cantata “Happy Moment”, the premieres of which were timed to coincide with the Congress of Vienna and brought Beethoven an unheard of success. However, in other writings of 4-5. reflected persistent and sometimes painful search for new ways. At this time, cello (Nos. 27, 28) and piano (Nos. 1815, XNUMX) sonatas were written, several dozen arrangements of songs of different nations for voice with an ensemble, the first vocal cycle in the history of the genre “To a Distant Beloved” (XNUMX). The style of these works is, as it were, experimental, with many brilliant discoveries, but not always as solid as in the period of “revolutionary classicism.”

The last decade of Beethoven’s life was overshadowed both by the general oppressive political and spiritual atmosphere in Metternich’s Austria, and by personal hardships and upheavals. The composer’s deafness became complete; since 1818, he was forced to use “conversational notebooks” in which interlocutors wrote questions addressed to him. Having lost hope for personal happiness (the name of the “immortal beloved”, to whom Beethoven’s farewell letter of July 6-7, 1812 is addressed, remains unknown; some researchers consider her J. Brunswick-Deym, others – A. Brentano), Beethoven took on taking care of raising his nephew Karl, the son of his younger brother who died in 1815. This led to a long-term (1815-20) legal battle with the boy’s mother over the rights to sole custody. A capable but frivolous nephew gave Beethoven a lot of grief. The contrast between sad and sometimes tragic life circumstances and the ideal beauty of the created works is a manifestation of the spiritual feat that made Beethoven one of the heroes of the European culture of modern times.

Creativity 1817-26 marked a new rise of Beethoven’s genius and at the same time became the epilogue of the era of musical classicism. Until the last days, remaining faithful to classical ideals, the composer found new forms and means of their embodiment, bordering on the romantic, but not passing into them. Beethoven’s late style is a unique aesthetic phenomenon. Beethoven’s central idea of the dialectical relationship of contrasts, the struggle between light and darkness, acquires an emphatically philosophical sound in his later work. Victory over suffering is no longer given through heroic action, but through the movement of the spirit and thought. The great master of the sonata form, in which dramatic conflicts developed before, Beethoven in his later compositions often refers to the fugue form, which is most suitable for embodying the gradual formation of a generalized philosophical idea. The last 5 piano sonatas (Nos. 28-32) and the last 5 quartets (Nos. 12-16) are distinguished by a particularly complex and refined musical language that requires the greatest skill from the performers, and penetrating perception from the listeners. 33 variations on a waltz by Diabelli and Bagatelli, op. 126 are also true masterpieces, despite the difference in scale. Beethoven’s late work was controversial for a long time. Of his contemporaries, only a few were able to understand and appreciate his last writings. One of these people was N. Golitsyn, on whose order quartets Nos. 12, 13 and 15 were written and dedicated to. The overture The Consecration of the House (1822) is also dedicated to him.

In 1823, Beethoven completed the Solemn Mass, which he himself considered his greatest work. This mass, designed more for a concert than for a cult performance, became one of the milestone phenomena in the German oratorio tradition (G. Schütz, J. S. Bach, G. F. Handel, W. A. Mozart, J. Haydn). The first mass (1807) was not inferior to the masses of Haydn and Mozart, but did not become a new word in the history of the genre, like the “Solemn”, in which all the skill of Beethoven as a symphonist and playwright was realized. Turning to the canonical Latin text, Beethoven singled out in it the idea of self-sacrifice in the name of the happiness of people and introduced into the final plea for peace the passionate pathos of denying war as the greatest evil. With the assistance of Golitsyn, the Solemn Mass was first performed on April 7, 1824 in St. Petersburg. A month later, Beethoven’s last benefit concert took place in Vienna, in which, in addition to parts from the Mass, his final, Ninth Symphony was performed with the final chorus to the words of F. Schiller’s “Ode to Joy”. The idea of overcoming suffering and the triumph of light is consistently carried through the entire symphony and is expressed with utmost clarity at the end thanks to the introduction of a poetic text that Beethoven dreamed of setting to music in Bonn. The Ninth Symphony with its final call – “Hug, millions!” – became Beethoven’s ideological testament to mankind and had a strong influence on the symphony of the XNUMXth and XNUMXth centuries.

G. Berlioz, F. Liszt, I. Brahms, A. Bruckner, G. Mahler, S. Prokofiev, D. Shostakovich accepted and continued Beethoven’s traditions in one way or another. As their teacher, Beethoven was also honored by the composers of the Novovensk school – the “father of dodecaphony” A. Schoenberg, the passionate humanist A. Berg, the innovator and lyricist A. Webern. In December 1911, Webern wrote to Berg: “There are few things so wonderful as the feast of Christmas. … Shouldn’t Beethoven’s birthday be celebrated this way too?”. Many musicians and music lovers would agree with this proposal, because for thousands (perhaps millions) of people, Beethoven remains not only one of the greatest geniuses of all times and peoples, but also the personification of an unfading ethical ideal, the inspirer of the oppressed, the comforter of the suffering, the faithful friend in sorrow and joy.

L. Kirillina

- Life and creative path →

- Symphonic creativity →

- Concert →

- Piano creativity →

- Piano sonatas →

- Violin sonatas →

- Variations →

- Chamber-instrumental creativity →

- Vocal creativity →

- Beethoven-pianist →

- Beethoven Music Academies →

- Overtures →

- List of works →

- Beethoven’s influence on the music of the future →

Beethoven is one of the greatest phenomena of world culture. His work takes a place on a par with the art of such titans of artistic thought as Tolstoy, Rembrandt, Shakespeare. In terms of philosophical depth, democratic orientation, courage of innovation, Beethoven has no equal in the musical art of Europe of the past centuries.

The work of Beethoven captured the great awakening of the peoples, the heroism and drama of the revolutionary era. Addressing all advanced humanity, his music was a bold challenge to the aesthetics of the feudal aristocracy.

Beethoven’s worldview was formed under the influence of the revolutionary movement that spread in the advanced circles of society at the turn of the XNUMXth and XNUMXth centuries. As its original reflection on German soil, the bourgeois-democratic Enlightenment took shape in Germany. The protest against social oppression and despotism determined the leading directions of German philosophy, literature, poetry, theater and music.

Lessing raised the banner of struggle for the ideals of humanism, reason and freedom. The works of Schiller and the young Goethe were imbued with civic feeling. The playwrights of the Sturm und Drang movement rebelled against the petty morality of feudal-bourgeois society. The reactionary nobility is challenged in Lessing’s Nathan the Wise, Goethe’s Goetz von Berlichingen, Schiller’s The Robbers and Insidiousness and Love. The ideas of the struggle for civil liberties permeate Schiller’s Don Carlos and William Tell. The tension of social contradictions was also reflected in the image of Goethe’s Werther, “the rebellious martyr”, in the words of Pushkin. The spirit of challenge marked every outstanding work of art of that era, created on German soil. Beethoven’s work was the most general and artistically perfect expression in the art of the popular movements in Germany at the turn of the XNUMXth and XNUMXth centuries.

The great social upheaval in France had a direct and powerful effect on Beethoven. This brilliant musician, a contemporary of the revolution, was born in an era that perfectly matched the warehouse of his talent, his titanic nature. With rare creative power and emotional acuity, Beethoven sang the majesty and intensity of his time, its stormy drama, the joys and sorrows of the gigantic masses of the people. To this day, Beethoven’s art remains unsurpassed as an artistic expression of feelings of civic heroism.

The revolutionary theme by no means exhausts Beethoven’s legacy. Undoubtedly, the most outstanding works of Beethoven belong to the art of the heroic-dramatic plan. The main features of his aesthetics are most vividly embodied in works that reflect the theme of struggle and victory, glorifying the universal democratic beginning of life, the desire for freedom. The Heroic, Fifth and Ninth symphonies, the overtures Coriolanus, Egmont, Leonora, Pathetique Sonata and Appassionata – it was this circle of works that almost immediately won Beethoven the widest worldwide recognition. And in fact, Beethoven’s music differs from the structure of thought and manner of expression of its predecessors primarily in its effectiveness, tragic power, and grandiose scale. There is nothing surprising in the fact that his innovation in the heroic-tragic sphere, earlier than in others, attracted general attention; mainly on the basis of Beethoven’s dramatic works, both his contemporaries and the generations immediately following them made a judgment about his work as a whole.

However, the world of Beethoven’s music is stunningly diverse. There are other fundamentally important aspects in his art, outside of which his perception will inevitably be one-sided, narrow, and therefore distorted. And above all, this is the depth and complexity of the intellectual principle inherent in it.

The psychology of the new man, liberated from feudal fetters, is revealed by Beethoven not only in a conflict-tragedy plan, but also through the sphere of high inspirational thought. His hero, possessing indomitable courage and passion, is endowed at the same time with a rich, finely developed intellect. He is not only a fighter, but also a thinker; along with action, he has a tendency to concentrated reflection. Not a single secular composer before Beethoven achieved such philosophical depth and scale of thought. In Beethoven, the glorification of real life in its multifaceted aspects was intertwined with the idea of the cosmic greatness of the universe. Moments of inspired contemplation in his music coexist with heroic-tragic images, illuminating them in a peculiar way. Through the prism of a sublime and deep intellect, life in all its diversity is refracted in Beethoven’s music – stormy passions and detached dreaminess, theatrical dramatic pathos and lyrical confession, pictures of nature and scenes of everyday life …

Finally, against the background of the work of its predecessors, Beethoven’s music stands out for that individualization of the image, which is associated with the psychological principle in art.

Not as a representative of the estate, but as a person with his own rich inner world, a man of a new, post-revolutionary society realized himself. It was in this spirit that Beethoven interpreted his hero. He is always significant and unique, each page of his life is an independent spiritual value. Even motifs that are related to each other in type acquire in Beethoven’s music such a richness of shades in conveying mood that each of them is perceived as unique. With an unconditional commonality of ideas that permeate all of his work, with a deep imprint of a powerful creative individuality that lies on all Beethoven’s works, each of his opuses is an artistic surprise.

Perhaps it is this unquenchable desire to reveal the unique essence of each image that makes the problem of Beethoven’s style so difficult.

Beethoven is usually spoken of as a composer who, on the one hand, completes the classicist (In domestic theater studies and foreign musicological literature, the term “classicist” has been established in relation to the art of classicism. Thus, finally, the confusion that inevitably arises when the single word “classical” is used to characterize the pinnacle, “eternal” phenomena of any art, and to define one stylistic category, but we continue to use the term “classical” by inertia in relation to both the musical style of the XNUMXth century and classical examples in music of other styles (for example, romanticism, baroque, impressionism, etc.).) era in music, on the other hand, opens the way for the “romantic age”. In broad historical terms, such a formulation does not raise objections. However, it does little to understand the essence of Beethoven’s style itself. For, touching on some sides at certain stages of evolution with the work of the classicists of the XNUMXth century and the romantics of the next generation, Beethoven’s music actually does not coincide in some important, decisive features with the requirements of either style. Moreover, it is generally difficult to characterize it with the help of stylistic concepts that have developed on the basis of studying the work of other artists. Beethoven is inimitably individual. At the same time, it is so many-sided and multifaceted that no familiar stylistic categories cover all the diversity of its appearance.

With a greater or lesser degree of certainty, we can only speak of a certain sequence of stages in the composer’s quest. Throughout his career, Beethoven continuously expanded the expressive boundaries of his art, constantly leaving behind not only his predecessors and contemporaries, but also his own achievements of an earlier period. Nowadays, it is customary to marvel at the multi-style of Stravinsky or Picasso, seeing this as a sign of the special intensity of the evolution of artistic thought, characteristic of the 59th century. But Beethoven in this sense is in no way inferior to the above-named luminaries. It is enough to compare almost any arbitrarily chosen works of Beethoven to be convinced of the incredible versatility of his style. Is it easy to believe that the elegant septet in the style of the Viennese divertissement, the monumental dramatic “Heroic Symphony” and the deeply philosophical quartets op. XNUMX belong to the same pen? Moreover, they were all created within the same six-year period.

None of Beethoven’s sonatas can be distinguished as the most characteristic of the composer’s style in the field of piano music. Not a single work typifies his searches in the symphonic sphere. Sometimes, in the same year, Beethoven publishes works so contrasting with each other that at first glance it is difficult to recognize commonalities between them. Let us recall at least the well-known Fifth and Sixth symphonies. Every detail of thematism, every method of shaping in them is as sharply opposed to each other as the general artistic concepts of these symphonies are incompatible – the sharply tragic Fifth and the idyllic pastoral Sixth. If we compare the works created at different, relatively distant from each other stages of the creative path – for example, the First Symphony and the Solemn Mass, the quartets op. 18 and the last quartets, the Sixth and Twenty-ninth Piano Sonatas, etc., etc., then we will see creations so strikingly different from each other that at first impression they are unconditionally perceived as the product of not only different intellects, but also from different artistic eras. Moreover, each of the mentioned opuses is highly characteristic of Beethoven, each is a miracle of stylistic completeness.

One can speak about a single artistic principle that characterizes Beethoven’s works only in the most general terms: throughout the entire creative path, the composer’s style developed as a result of the search for a true embodiment of life. The powerful coverage of reality, richness and dynamics in the transmission of thoughts and feelings, finally a new understanding of beauty compared to its predecessors, led to such many-sided original and artistically unfading forms of expression that can only be generalized by the concept of a unique “Beethoven style”.

By Serov’s definition, Beethoven understood beauty as an expression of high ideological content. The hedonistic, gracefully divertissement side of musical expressiveness was consciously overcome in the mature work of Beethoven.

Just as Lessing stood for precise and parsimonious speech against the artificial, embellishing style of salon poetry, saturated with elegant allegories and mythological attributes, so Beethoven rejected everything decorative and conventionally idyllic.

In his music, not only the exquisite ornamentation, inseparable from the style of expression of the XNUMXth century, disappeared. The balance and symmetry of the musical language, the smoothness of rhythm, the chamber transparency of sound – these stylistic features, characteristic of all Beethoven’s Viennese predecessors without exception, were also gradually ousted from his musical speech. Beethoven’s idea of the beautiful demanded an underlined nakedness of feelings. He was looking for other intonations – dynamic and restless, sharp and stubborn. The sound of his music became saturated, dense, dramatically contrasting; his themes acquired hitherto unprecedented conciseness, severe simplicity. To people brought up on the musical classicism of the XNUMXth century, Beethoven’s manner of expression seemed so unusual, “unsmoothed”, sometimes even ugly, that the composer was repeatedly reproached for his desire to be original, they saw in his new expressive techniques the search for strange, deliberately dissonant sounds that cut the ear.

And, however, with all originality, courage and novelty, Beethoven’s music is inextricably linked with the previous culture and with the classicist system of thought.

The advanced schools of the XNUMXth century, covering several artistic generations, prepared Beethoven’s work. Some of them received a generalization and final form in it; the influences of others are revealed in a new original refraction.

Beethoven’s work is most closely associated with the art of Germany and Austria.

First of all, there is a perceptible continuity with the Viennese classicism of the XNUMXth century. It is no coincidence that Beethoven entered the history of Culture as the last representative of this school. He began on the path laid down by his immediate predecessors Haydn and Mozart. Beethoven also deeply perceived the structure of the heroic-tragic images of Gluck’s musical drama, partly through the works of Mozart, which in their own way refracted this figurative beginning, partly directly from Gluck’s lyrical tragedies. Beethoven is equally clearly perceived as the spiritual heir of Handel. The triumphant, light-heroic images of Handel’s oratorios began a new life on an instrumental basis in Beethoven’s sonatas and symphonies. Finally, clear successive threads connect Beethoven with that philosophical and contemplative line in the art of music, which has long been developed in the choral and organ schools of Germany, becoming its typical national beginning and reaching its pinnacle expression in the art of Bach. The influence of Bach’s philosophical lyrics on the entire structure of Beethoven’s music is deep and undeniable and can be traced from the First Piano Sonata to the Ninth Symphony and the last quartets created shortly before his death.

Protestant chorale and traditional everyday German song, democratic singspiel and Viennese street serenades – these and many other types of national art are also uniquely embodied in Beethoven’s work. It recognizes both the historically established forms of peasant songwriting and the intonations of modern urban folklore. In essence, everything organically national in the culture of Germany and Austria was reflected in Beethoven’s sonata-symphony work.

The art of other countries, especially France, also contributed to the formation of his multifaceted genius. Beethoven’s music echoes the Rousseauist motifs that were embodied in French comic opera in the XNUMXth century, starting with Rousseau’s The Village Sorcerer and ending with Gretry’s classical works in this genre. The poster, sternly solemn nature of the mass revolutionary genres of France left an indelible mark on it, marking a break with the chamber art of the XNUMXth century. Cherubini’s operas brought sharp pathos, spontaneity and dynamics of passions, close to the emotional structure of Beethoven’s style.

Just as the work of Bach absorbed and generalized at the highest artistic level all the significant schools of the previous era, so the horizons of the brilliant symphonist of the XNUMXth century embraced all the viable musical currents of the previous century. But Beethoven’s new understanding of musical beauty reworked these sources into such an original form that in the context of his works they are by no means always easily recognizable.

In exactly the same way, the classicist structure of thought is refracted in Beethoven’s work in a new form, far from the style of expression of Gluck, Haydn, Mozart. This is a special, purely Beethovenian variety of classicism, which has no prototypes in any artist. Composers of the XNUMXth century did not even think about the very possibility of such grandiose constructions that became typical for Beethoven, like freedom of development within the framework of sonata formation, about such diverse types of musical thematics, and the complexity and richness of the very texture of Beethoven’s music should have been perceived by them as unconditional a step back to the rejected manner of the Bach generation. Nevertheless, Beethoven’s belonging to the classicist structure of thought clearly emerges against the background of those new aesthetic principles that began to unconditionally dominate the music of the post-Beethoven era.

From the first to the last works, Beethoven’s music is invariably characterized by clarity and rationality of thinking, monumentality and harmony of form, excellent balance between the parts of the whole, which are characteristic features of classicism in art in general, in music in particular. In this sense, Beethoven can be called a direct successor not only to Gluck, Haydn and Mozart, but also to the very founder of the classicist style in music, the Frenchman Lully, who worked a hundred years before Beethoven was born. Beethoven showed himself most fully within the framework of those sonata-symphonic genres that were developed by the composers of the Enlightenment and reached the classical level in the work of Haydn and Mozart. He is the last composer of the XNUMXth century, for whom the classicist sonata was the most natural, organic form of thinking, the last one for whom the internal logic of musical thought dominates the external, sensually colorful beginning. Perceived as a direct emotional outpouring, Beethoven’s music actually rests on a virtuoso erected, tightly welded logical foundation.

There is, finally, another fundamentally important point connecting Beethoven with the classicist system of thought. This is the harmonious worldview reflected in his art.

Of course, the structure of feelings in Beethoven’s music is different from that of the composers of the Enlightenment. Moments of peace of mind, peace, peace far from dominate it. The enormous charge of energy characteristic of Beethoven’s art, the high intensity of feelings, intense dynamism push idyllic “pastoral” moments into the background. And yet, like the classical composers of the XNUMXth century, a sense of harmony with the world is the most important feature of Beethoven’s aesthetics. But it is born almost invariably as a result of a titanic struggle, the utmost exertion of spiritual forces overcoming gigantic obstacles. As a heroic affirmation of life, as a triumph of a won victory, Beethoven has a feeling of harmony with humanity and the universe. His art is imbued with that faith, strength, intoxication with the joy of life, which came to an end in music with the advent of the “romantic age”.

Concluding the era of musical classicism, Beethoven at the same time opened the way for the coming century. His music rises above everything that was created by his contemporaries and the next generation, sometimes echoing the quests of a much later time. Beethoven’s insights into the future are amazing. Until now, the ideas and musical images of the brilliant Beethoven’s art have not been exhausted.

V. Konen

- Life and creative path →

- Beethoven’s influence on the music of the future →