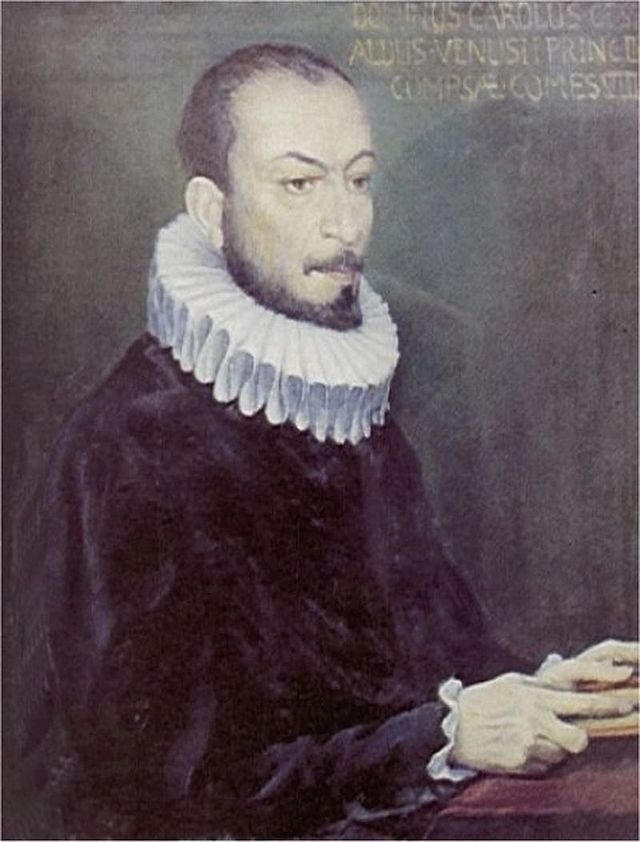

Carlo Gesualdo di Venosa |

Carlo Gesualdo from Venosa

By the end of the XNUMXth century and at the beginning of the XNUMXth century, a new impulse seized the Italian madrigal due to the introduction of chromatism. As a reaction against the obsolete choral art based on the diatonic, a great fermentation begins, from which the opera and oratorio will in turn arise. Cipriano da Pope, Gesualdo di Venosa, Orazio Vecchi, Claudio Monteverdi contribute to such an intensive evolution with their innovative work. K. Nef

The work of C. Gesualdo stands out for its unusualness, it belongs to a complex, critical historical era – the transition from the Renaissance to the XNUMXth century, which influenced the fate of many outstanding artists. Recognized by his contemporaries as “the head of music and musical poets,” Gesualdo was one of the most daring innovators in the field of madrigal, the leading genre of secular music of Renaissance art. It is no coincidence that Carl Nef calls Gesualdo “a romantic and expressionist of the XNUMXth century.”

The old aristocratic family to which the composer belonged was one of the most distinguished and influential in Italy. Family ties connected his family with the highest church circles – his mother was the niece of the Pope, and his father’s brother was a cardinal. The exact date of the composer’s birth is unknown. The boy’s versatile musical talent manifested itself quite early – he learned to play the lute and other musical instruments, sang and composed music. The surrounding atmosphere contributed a lot to the development of natural abilities: the father kept a chapel in his castle near Naples, in which many famous musicians worked (including madrigalists Giovanni Primavera and Pomponio Nenna, who is considered Gesualdo’s mentor in the field of composition). The young man’s interest in the musical culture of the ancient Greeks, who knew, in addition to diatonicism, chromatism and anharmonism (the 3 main modal inclinations or “kinds” of ancient Greek music), led him to persistent experimentation in the field of melodic-harmonic means. Already the early madrigals of Gesualdo are distinguished by their expressiveness, emotionality and sharpness of the musical language. Close acquaintance with the major Italian poets and literary theorists T. Tasso, G. Guarini opened up new horizons for the composer’s work. He is occupied with the problem of the relationship between poetry and music; in his madrigals, he seeks to achieve the complete unity of these two principles.

Gesualdo’s personal life develops dramatically. In 1586 he married his cousin, Dona Maria d’Avalos. This union, sung by Tasso, turned out to be unhappy. In 1590, having learned about his wife’s infidelity, Gesualdo killed her and her lover. The tragedy left a gloomy imprint on the life and work of an outstanding musician. Subjectivism, increased exaltation of feelings, drama and tension distinguish his madrigals of 1594-1611.

The collections of his five-voice and six-voice madrigals, repeatedly reprinted during the composer’s lifetime, captured the evolution of Gesualdo’s style – expressive, subtly refined, marked by special attention to expressive details (accentuation of individual words of a poetic text with the help of an unusually high tessitura of a vocal part, a sharp-sounding harmonic vertical, whimsically rhythmic melodic phrases ). In poetry, the composer chooses texts that strictly correspond to the figurative system of his music, which was expressed by feelings of deep sorrow, despair, anguish, or moods of languid lyrics, sweet flour. Sometimes only one line became a source of poetic inspiration for creating a new madrigal, many works were written by the composer on his own texts.

In 1594, Gesualdo moved to Ferrara and married Leonora d’Este, a representative of one of the most noble aristocratic families in Italy. Just as in his youth, in Naples, the entourage of the Venous prince were poets, singers and musicians, in the new house of Gesualdo, music lovers and professional musicians gather in Ferrara, and the noble philanthropist combines them into an academy “to improve musical taste.” In the last decade of his life, the composer turned to the genres of sacred music. In 1603 and 1611 collections of his spiritual writings are published.

The art of the outstanding master of the late Renaissance is original and brightly individual. With its emotional power, increased expressiveness, it stands out among those created by Gesualdo’s contemporaries and predecessors. At the same time, the composer’s work clearly shows features characteristic of the entire Italian and, more broadly, European culture at the turn of the XNUMXth and XNUMXth centuries. The crisis of the humanistic culture of the High Renaissance, the disappointment in its ideals contributed to the subjectivization of artists’ creativity. The emerging style in the art of a turning point era was called “mannerism”. His aesthetic postulates were not following nature, an objective view of reality, but the subjective “inner idea” of the artistic image, born in the artist’s soul. Reflecting on the ephemeral nature of the world and the precariousness of human destiny, on the dependence of man on the mysterious mystical irrational forces, the artists created works imbued with tragedy and exaltation with accentuated dissonance, disharmony of images. To a large extent, these features are also characteristic of the art of Gesualdo.

N. Yavorskaya