Arturo Toscanini (Arturo Toscanini) |

Arturo Toscanini

- Arturo Toscanini. Great maestro →

- Feat Toscanini →

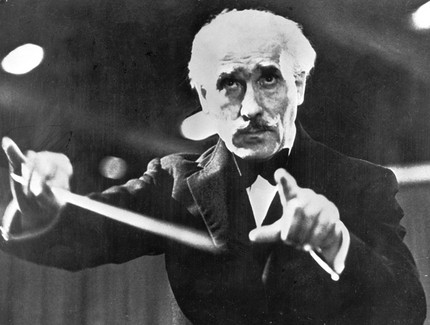

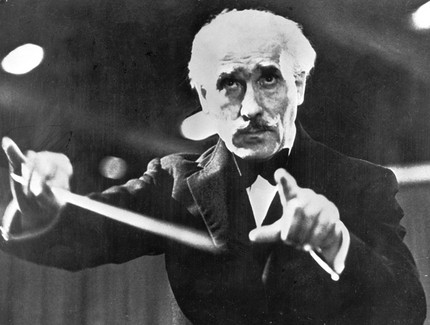

A whole era in the art of conducting is associated with the name of this musician. For almost seventy years he stood at the console, showing the world unsurpassed examples of the interpretation of works of all times and peoples. The figure of Toscanini became a symbol of devotion to art, he was a true knight of music, who did not know compromises in his desire to achieve the ideal.

Many pages have been written about Toscanini by writers, musicians, critics, and journalists. And all of them, defining the main feature in the creative image of the great conductor, speak of his endless striving for perfection. He was never satisfied either with himself or with the orchestra. Concert and theater halls literally shuddered with enthusiastic applause, in the reviews he was awarded the most excellent epithets, but for the maestro, only his musical conscience, which did not know peace, was the exacting judge.

“… In his person,” writes Stefan Zweig, “one of the most truthful people of our time serves the inner truth of a work of art, he serves with such fanatical devotion, with such inexorable rigor and at the same time humility, which we are unlikely to find today in any other field of creativity. Without pride, without arrogance, without self-will, he serves the highest will of the master he loves, serves with all the means of earthly service: the mediating power of the priest, the piety of the believer, the exacting rigor of the teacher and the tireless zeal of the eternal student … In art – such is his moral greatness, such is his human duty He recognizes only the perfect and nothing but the perfect. Everything else – quite acceptable, almost complete and approximate – does not exist for this stubborn artist, and if it does exist, then as something deeply hostile to him.

Toscanini identified his calling as a conductor relatively early. He was born in Parma. His father participated in the national liberation struggle of the Italian people under the banner of Garibaldi. Arturo’s musical abilities led him to the Parma Conservatory, where he studied cello. And a year after graduating from the conservatory, the debut took place. On June 25, 1886, he conducted the opera Aida in Rio de Janeiro. The triumphant success attracted the attention of musicians and musical figures to the name of Toscanini. Returning to his homeland, the young conductor worked for some time in Turin, and at the end of the century he headed the Milan theater La Scala. The productions performed by Toscanini in this opera center in Europe bring him worldwide fame.

In the history of the New York Metropolitan Opera, the period from 1908 to 1915 was truly “golden”. Then Toscanini worked here. Subsequently, the conductor spoke not particularly commendably about this theater. With his usual expansiveness, he told the music critic S. Khotsinov: “This is a pig barn, not an opera. They should burn it. It was a bad theater even forty years ago. I was invited to the Met many times, but I always said no. Caruso, Scotty came to Milan and told me: “No, maestro, the Metropolitan is not a theater for you. He’s good for making money, but he’s not serious.” And he continued, answering the question why he still performed at the Metropolitan: “Ah! I came to this theater because one day I was told that Gustav Mahler agreed to come there, and I thought to myself: if such a good musician as Mahler agrees to go there, the Met can’t be too bad. One of the best works of Toscanini on the stage of the New York theater was the production of Boris Godunov by Mussorgsky.

… Italy again. Again the theater “La Scala”, performances in symphony concerts. But Mussolini’s thugs came to power. The conductor openly showed his dislike for the fascist regime. “Duce” he called a pig and a murderer. In one of the concerts, he refused to perform the Nazi anthem, and later, in protest against racial discrimination, he did not participate in the Bayreuth and Salzburg musical celebrations. And the previous performances of Toscanini in Bayreuth and Salzburg were the decoration of these festivals. Only the fear of world public opinion prevented the Italian dictator from applying repressions against the outstanding musician.

Life in Fascist Italy becomes unbearable for Toscanini. For many years he leaves his native land. Having moved to the United States, the Italian conductor in 1937 becomes the head of the newly created symphony orchestra of the National Broadcasting Corporation – NBC. He travels to Europe and South America only on tour.

It is impossible to say in which area of conducting Toscanini’s talent manifested itself more clearly. His truly magic wand gave birth to masterpieces both on the opera stage and on the concert stage. Operas by Mozart, Rossini, Verdi, Wagner, Mussorgsky, R. Strauss, symphonies by Beethoven, Brahms, Tchaikovsky, Mahler, oratorios by Bach, Handel, Mendelssohn, orchestral pieces by Debussy, Ravel, Duke – each new reading was a discovery. Toscanini’s repertory sympathies knew no limits. Verdi’s operas were especially fond of him. In his programs, along with classical works, he often included modern music. So, in 1942, the orchestra he led became the first performer in the United States of Shostakovich’s Seventh Symphony.

Toscanini’s ability to embrace new works was unique. His memory surprised many musicians. Busoni once remarked: “… Toscanini has a phenomenal memory, an example of which is difficult to find in the entire history of music… He has just read Duke’s most difficult score – “Ariana and the Bluebeard” and the next morning appoints the first rehearsal by heart! .. “

Toscanini considered his main and only task to correctly and deeply embody what was written by the author in the notes. One of the soloists of the orchestra of the National Broadcasting Corporation, S. Antek, recalls: “Once, at a rehearsal of a symphony, I asked Toscanini during a break how he “made” her performance. “Very simple,” replied the maestro. – Performed the way it was written. It is certainly not easy, but there is no other way. Let the ignorant conductors, confident that they are above the Lord God himself, do what they please. You have to have the courage to play the way it’s written.” I remember another remark by Toscanini after the dress rehearsal of Shostakovich’s Seventh (“Leningrad”) Symphony… “It’s written that way,” he said wearily, descending the steps of the stage. “Now let others begin their ‘interpretations’. To perform works “as they are written”, to perform “exactly” – this is his musical credo.

Each rehearsal of Toscanini is an ascetic work. He did not know any pity either for himself or for the musicians. It has always been so: in youth, in adulthood, and in old age. Toscanini is indignant, screams, begs, tears his shirt, breaks his stick, makes the musicians repeat the same phrase again. No concessions – music is sacred! This internal impulse of the conductor was transmitted by invisible ways to each performer – the great artist was able to “tune” the souls of the musicians. And in this unity of people devoted to art, the perfect performance was born, which Toscanini dreamed of all his life.

L. Grigoriev, J. Platek