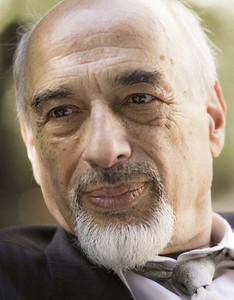

Yakov Vladimirovich Flier |

Yakov Flier

Yakov Vladimirovich Flier was born in Orekhovo-Zuevo. The family of the future pianist was far from music, although, as he later recalled, she was passionately loved in the house. Flier’s father was a modest craftsman, a watchmaker, and his mother was a housewife.

Yasha Flier made his first steps in art virtually self-taught. Without anyone’s help, he learned to pick by ear, independently figured out the intricacies of musical notation. However, later the boy began to give piano lessons to Sergei Nikanorovich Korsakov – a rather outstanding composer, pianist and teacher, a recognized “musical luminary” of Orekhovo-Zuev. According to Flier’s memoirs, Korsakov’s piano teaching method was distinguished by a certain originality – it did not recognize either scales, or instructive technical exercises, or special finger training.

- Piano music in the online store OZON.ru

The musical education and development of students was based solely on artistic and expressive material. Dozens of different uncomplicated plays by Western European and Russian authors were replayed in his class, and their rich poetic content was revealed to young musicians in fascinating conversations with the teacher. This, of course, had its pros and cons.

However, for some of the students, the most gifted by nature, this style of Korsakov’s work brought very effective results. Yasha Flier also progressed rapidly. A year and a half of intensive studies – and he has already approached Mozart’s sonatinas, simple miniatures by Schumann, Grieg, Tchaikovsky.

At the age of eleven, the boy was admitted to the Central Music School at the Moscow Conservatory, where G. P. Prokofiev first became his teacher, and a little later S. A. Kozlovsky. In the conservatory, where Yakov Flier entered in 1928, K. N. Igumnov became his piano teacher.

It is said that during his student years, Flier did not stand out much among his fellow students. True, they spoke of him with respect, paid tribute to his generous natural data and outstanding technical dexterity, but few could have imagined that this agile black-haired young man – one of many in the class of Konstantin Nikolayevich – was destined to become a famous artist in the future.

In the spring of 1933, Flier discussed with Igumnov the program of his graduation speech – in a few months he was to graduate from the conservatory. He spoke about Rachmaninov’s Third Concerto. “Yes, you just got arrogant,” cried Konstantin Nikolaevich. “Do you know that only a great master can do this thing ?!” Flier stood his ground, Igumnov was inexorable: “Do as you know, teach what you want, but please, then finish the conservatory on your own,” he ended the conversation.

I had to work on the Rachmaninov Concerto at my own peril and risk, almost secretly. In the summer, Flier almost did not leave the instrument. He studied with excitement and passion, unfamiliar to him before. And in the fall, after the holidays, when the doors of the conservatory opened again, he managed to persuade Igumnov to listen to Rachmaninov’s concerto. “Okay, but only the first part…” Konstantin Nikolayevich agreed glumly, sitting down to accompany the second piano.

Flier recalls that he was rarely as excited as on that memorable day. Igumnov listened in silence, not interrupting the game with a single remark. The first part has come to an end. “Are you still playing?” Without turning his head, he asked curtly. Of course, during the summer all the parts of Rachmaninov’s triptych were learned. When the chord cascades of the last pages of the final sounded, Igumnov abruptly got up from his chair and, without uttering a word, left the class. He didn’t come back for a long time, an excruciatingly long time for Flier. And soon the stunning news spread around the conservatory: the professor was seen crying in a secluded corner of the corridor. So touched him then Flierovskaya game.

Flier’s final examination took place in January 1934. By tradition, the Small Hall of the Conservatory was full of people. The crown number of the diploma program of the young pianist was, as expected, Rachmaninov’s concerto. Flier’s success was enormous, for most of those present – downright sensational. Eyewitnesses recall that when the young man, having put an end to the final chord, got up from the instrument, for several moments a complete stupor reigned among the audience. Then the silence was broken by such a flurry of applause, which was not remembered here. Then, “when the Rachmaninoff concert that shook the hall died down, when everything quieted down, calmed down and the listeners started talking among themselves, they suddenly noticed that they were speaking in a whisper. Something very big and serious happened, to which the whole hall was a witness. Experienced listeners sat here – students of the conservatory and professors. They spoke now in muffled voices, afraid to frighten off their own excitement. (Tess T. Yakov Flier // Izvestia. 1938. June 1.).

The graduation concert was a huge victory for Flier. Others followed; not one, not two, but a brilliant series of victories over the course of some few years. 1935 – championship at the Second All-Union Competition of Performing Musicians in Leningrad. A year later – success at the International Competition in Vienna (first prize). Then Brussels (1938), the most important test for any musician; Flier has an honorable third prize here. The rise was truly dizzying – from success in the Conservative exam to world fame.

Flier now has its own audience, vast and dedicated. “Flierists”, as the artist’s fans were called in the thirties, crowded the halls during the days of his performances, enthusiastically responded to his art. What inspired the young musician?

Genuine, rare ardor of experience – first of all. Flier’s playing was a passionate impulse, a loud pathos, an excited drama of musical experience. Like no one else, he was able to captivate the audience with “nervous impulsiveness, sharpness of sound, instantly soaring, as if foaming sound waves” (Alshwang A. Soviet Schools of Pianoism // Sov. Music. 1938. No. 10-11. P. 101.).

Of course, he also had to be different, to adapt to the various requirements of the performed works. And yet his fiery artistic nature was most in tune with what was marked in the notes with remarks Furioso, Concitato, Eroico, con brio, con tutta Forza; his native element was where fortissimo and heavy emotional pressure reigned in music. At such moments, he literally captivated the audience with the power of his temperament, with indomitable and imperious determination he subordinated the listener to his performing will. And therefore “it is difficult to resist the artist, even if his interpretation does not coincide with the prevailing ideas” (Adzhemov K. Romantic Gift // Sov. Music. 1963. No. 3. P. 66.), says one critic. Another says: “His (Fliera.— Mr. C.) romantically elevated speech acquires a special power of influence at moments that require the greatest tension from the performer. Imbued with oratorical pathos, it most powerfully manifests itself in the extreme registers of expressiveness. (Shlifshtein S. Soviet Laureates // Sov. Music. 1938. No. 6. P. 18.).

Enthusiasm sometimes led Flier to performing exaltation. In frenzied accelerando, it used to be that a sense of proportion was lost; the incredible pace that the pianist loved did not allow him to fully “pronounce” the musical text, forced him “to go for some “reduction” in the number of expressive details” (Rabinovich D. Three laureates // Sov. art. 1938. 26 April). It happened that darkened the musical fabric and excessively abundant pedalization. Igumnov, who never got tired of repeating to his students: “The limit of a fast pace is the ability to really hear every sound” (Milstein Ya. Performing and pedagogical principles of K. N. Igumnov // Masters of the Soviet pianistic school. – M., 1954. P. 62.), – more than once advised Flier “to moderate somewhat his sometimes overflowing temperament, leading to unnecessarily fast tempos and sometimes to sound overload” (Igumnov K. Yakov Flier // Sov. Music. 1937. No. 10-11. P. 105.).

The peculiarities of Flier’s artistic nature as a performer largely predetermined his repertoire. In the pre-war years, his attention was focused on the romantics (primarily Liszt and Chopin); he also showed great interest in Rachmaninov. It was here that he found his true performing “role”; according to the critics of the thirties, Flier’s interpretations of the works of these composers had on the public “a direct, enormous artistic impression” (Rabinovich D. Gilels, Flier, Oborin // Music. 1937. Oct.). Moreover, he especially loved the demonic, infernal Leaf; heroic, courageous Chopin; dramatically agitated Rachmaninov.

The pianist was close not only to the poetics and figurative world of these authors. He was also impressed by their magnificently decorative piano style – that dazzling multicolor of textured outfits, the luxury of pianistic decoration, which are inherent in their creations. Technical obstacles did not bother him too much, most of them he overcame without visible effort, easily and naturally. “Flier’s large and small technique are equally remarkable… The young pianist has reached that stage of virtuosity when technical perfection in itself becomes a source of artistic freedom” (Kramskoy A. Art that delights // Soviet art. 1939. Jan. 25).

A characteristic moment: it is least of all possible to define Flier’s technique at that time as “inconspicuous”, to say that she was assigned only a service role in his art.

On the contrary, it was a daring and courageous virtuosity, openly proud of its power over the material, shining brightly in bravura, imposing pianistic canvases.

Old-timers of concert halls recall that, turning to the classics in his youth, the artist, willy-nilly, “romanticized” them. Sometimes he was even reproached: “Flier does not fully switch himself into a new emotional “system” when performed by different composers” (Kramskoy A. Art that delights // Soviet art. 1939. Jan. 25). Take, for example, his interpretation of Beethoven’s Appasionata. With all the fascinating that the pianist brought to the sonata, his interpretation, according to contemporaries, by no means served as a standard of strict classical style. This happened not only with Beethoven. And Flier knew it. It is no coincidence that a very modest place in his repertoire was occupied by such composers as Scarlatti, Haydn, Mozart. Bach was represented in this repertoire, but mainly by arrangements and transcriptions. The pianist did not turn too often to Schubert, Brahms either. In a word, in that literature where spectacular and catchy technique, wide pop scope, fiery temperament, excessive generosity of emotions turned out to be enough for the success of the performance, he was a wonderful interpreter; where an exact constructive calculation was required, an intellectual-philosophical analysis sometimes turned out to be not at such a significant height. And strict criticism, paying tribute to his achievements, did not consider it necessary to circumvent this fact. “Flier’s failures speak only of the well-known narrowness of his creative aspirations. Instead of constantly expanding his repertoire, enriching his art with a deep penetration into the most diverse styles, and Flier has more than anyone else to do this, he limits himself to a very bright and strong, but somewhat monotonous manner of performance. (In the theater they say in such cases that the artist does not play a role, but himself) ” (Grigoriev A. Ya. Flier // Soviet Art. 1937. 29 Sept.). “So far, in the performance of Flier, we often feel the huge scale of his pianistic talent, rather than the scale of a deep, full of philosophical generalization of thought” (Kramskoy A. Art that delights // Soviet art. 1939. Jan. 25).

Perhaps the criticism was right and wrong. Rights, advocating for the expansion of Flier’s repertoire, for the development of new stylistic worlds by the pianist, for the further expansion of his artistic and poetic horizons. At the same time, he is not entirely right in blaming the young man for the insufficient “scale of a deep, complete philosophical generalization of thought.” Reviewers took into account a lot – and the features of technology, and artistic inclinations, and the composition of the repertoire. Forgotten sometimes only about age, life experience and the nature of individuality. Not everyone is destined to be born a philosopher; individuality is always plus something and minus something.

The characterization of Flier’s performance would be incomplete without mentioning one more thing. The pianist was able in his interpretations to concentrate entirely on the central image of the composition, without being distracted by secondary, secondary elements; he was able to reveal and shade in relief the through development of this image. As a rule, his interpretations of piano pieces resembled sound pictures, which seemed to be viewed by listeners from a distant distance; this made it possible to clearly see the “foreground”, to unmistakably understand the main thing. Igumnov always liked it: “Flier,” he wrote, “aspires, first of all, to the integrity, organicity of the performed work. He is most interested in the general line, he tries to subordinate all the details to the living manifestation of what seems to him the very essence of the work. Therefore, he is not inclined to give equivalence to each detail or to stick out some of them to the detriment of the whole.

… The brightest thing, – Konstantin Nikolayevich concluded, – Flier’s talent is manifested when he takes on large canvases … He succeeds in improvisational-lyrical and technical pieces, but he plays Chopin’s mazurkas and waltzes weaker than he could! Here you need that filigree, that jewelry finish, which is not close to Flier’s nature and which he still needs to develop. (Igumnov K. Yakov Flier // Sov. Music. 1937. No. 10-11. P. 104.).

Indeed, monumental piano works formed the foundation of Flier’s repertoire. We can name at least the A-major concerto and both Liszt’s sonatas, Schumann’s Fantasy and Chopin’s B-flat minor sonata, Mussorgsky’s Beethoven’s “Appassionata” and “Pictures at an Exhibition”, the large cyclic forms of Ravel, Khachaturian, Tchaikovsky, Prokofiev, Rachmaninov and others authors. Such a repertoire, of course, was not accidental. The specific requirements imposed by the music of large forms corresponded to many features of the natural gift and the artistic constitution of Flier. It was in the broad sound constructions that the strengths of this gift were most clearly revealed (hurricane temperament, freedom of rhythmic breathing, variety scope), and … less strong ones were hidden (Igumnov mentioned them in connection with Chopin’s miniatures).

Summarizing, we emphasize: the successes of the young master were strong because they were won from the mass, popular audiences that filled the concert halls in the twenties and thirties. The general public was clearly impressed by Flier’s performing credo, the ardor and courage of his game, his brilliant variety artistry, were at heart. “This is a pianist,” G. G. Neuhaus wrote at that time, “speaking to the masses in an imperious, ardent, convincing musical language, intelligible even to a person with little experience in music” (Neigauz G. G. The triumph of Soviet musicians // Koms. Pravda 1938. June 1.).

…And then suddenly trouble came. From the end of 1945, Flier began to feel that something was wrong with his right hand. Noticeably weakened, lost activity and dexterity of one of the fingers. Doctors were at a loss, and in the meantime, the hand was getting worse and worse. At first, the pianist tried to cheat with the fingering. Then he began to abandon unbearable piano pieces. His repertoire was quickly reduced, the number of performances was catastrophically reduced. By 1948, Flier only occasionally takes part in open concerts, and even then mainly in modest chamber-ensemble evenings. He seems to be fading into the shadows, lost sight of music lovers…

But the Flier-teacher declares himself louder and louder in these years. Forced to retire from the stage of the concert stage, he devoted himself entirely to teaching. And quickly made progress; among his students were B. Davidovich, L. Vlasenko, S. Alumyan, V. Postnikova, V. Kamyshov, M. Pletnev… Flier was a prominent figure in Soviet piano pedagogy. Acquaintance, even if brief, with his views on the education of young musicians, no doubt, is interesting and instructive.

“… The main thing,” said Yakov Vladimirovich, “is to help the student to comprehend as accurately and deeply as possible what is called the main poetic intention (idea) of the composition. For only from many comprehensions of many poetic ideas the very process of formation of the future musician is formed. Moreover, it was not enough for Flier that the student understood the author in some single and specific case. He demanded more – understanding style in all its fundamental patterns. “It is permissible to take on masterpieces of piano literature only after having mastered well the creative manner of the composer who created this masterpiece” (The statements of Ya. V. Flier are quoted from the notes of conversations with him by the author of the article.).

Issues related to different performing styles occupied a large place in Flier’s work with students. Much has been said about them, and they have been comprehensively analyzed. In the class, for example, one could hear such remarks: “Well, in general, it’s not bad, but perhaps you are too “chopinizing” this author.” (A rebuke to a young pianist who used excessively bright expressive means in interpreting one of Mozart’s sonatas.) Or: “Don’t flaunt your virtuosity too much. Still, this is not Liszt” (in connection with Brahms’ “Variations on a Theme of Paganini”). When listening to a play for the first time, Flier usually did not interrupt the performer, but let him speak to the end. For the professor, stylistic coloring was important; evaluating the sound picture as a whole, he determined the degree of its stylistic authenticity, artistic truth.

Flier was absolutely intolerant of arbitrariness and anarchy in performance, even if all this was “flavored” by the most direct and intense experience. Students were brought up by him on the unconditional recognition of the priority of the composer’s will. “The author should be trusted more than any of us,” he never tired of inspiring the youth. “Why don’t you trust the author, on what basis?” – he reproached, for example, a student who thoughtlessly altered the performing plan prescribed by the creator of the work himself. With newcomers in his class, Flier sometimes undertook a thorough, downright scrupulous analysis of the text: as if through a magnifying glass, the smallest patterns of the sound fabric of the work were examined, all the author’s remarks and designations were comprehended. “Get used to taking the maximum from the instructions and wishes of the composer, from all the strokes and nuances fixed by him in the notes,” he taught. “Young people, unfortunately, do not always look closely at the text. You often listen to a young pianist and see that he has not identified all the elements of the piece’s texture, and has not thought through many of the author’s recommendations. Sometimes, of course, such a pianist simply lacks skill, but often this is the result of insufficiently inquisitive study of the work.

“Of course,” continued Yakov Vladimirovich, “an interpretative scheme, even sanctioned by the author himself, is not something unchanging, not subject to one or another adjustment on the part of the artist. On the contrary, the opportunity (moreover, the necessity!) to express one’s innermost poetic “I” through the attitude to the work is one of the enchanting mysteries of performance. Remarque – the expression of the composer’s will – is extremely important for the interpreter, but it is not a dogma either. However, the Flier teacher nevertheless proceeded from the following: “First, do, as perfectly as possible, what the author wants, and then … Then we will see.”

Having set any performance task for the student, Flier did not at all consider that his functions as a teacher had been exhausted. On the contrary, he immediately outlined ways to solve this problem. As a rule, right there, on the spot, he experimented with fingering, delved into the essence of the necessary motor processes and finger sensations, tried various options with pedaling, etc. Then he summarized his thoughts in the form of specific instructions and advice. “I think that in pedagogy one cannot limit oneself to explaining to the student that it is required of him to formulate a goal, so to speak. Как gotta do how to achieve the desired – the teacher must also show this. Especially if he is an experienced pianist … “

Of undoubted interest are Flier’s ideas about how and in what sequence new musical material should be mastered. “The inexperience of young pianists often pushes them onto the wrong path,” he remarked. , superficial acquaintance with the text. Meanwhile, the most useful thing for the development of musical intellect is to carefully follow the logic of the development of the author’s thought, to understand the structure of the work. Especially if this work is “made” not just…”

So, at first it is important to cover the play as a whole. Let it be a game close to reading from a sheet, even if a lot of technically does not come out. All the same, it is necessary to look at the musical canvas with a single glance, to try, as Flier said, to “fall in love” with it. And then start learning “in pieces”, detailed work on which is already the second stage.

Putting his “diagnosis” in connection with certain defects in student performance, Yakov Vladimirovich was always extremely clear in his wording; his remarks were distinguished by concreteness and certainty, they were directed precisely to the target. In the classroom, especially when dealing with undergraduates, Flier was usually very laconic: “When studying with a student whom you have known for a long time and well, many words are not needed. Over the years comes a complete understanding. Sometimes two or three phrases, or even just a hint, are enough … ”At the same time, revealing his thought, Flier knew how and loved to find colorful forms of expression. His speech was sprinkled with unexpected and figurative epithets, witty comparisons, spectacular metaphors. “Here you need to move like a somnambulist …” (about music filled with a sense of detachment and numbness). “Play, please, in this place with absolutely empty fingers” (about the episode that should be performed leggierissimo). “Here I would like a little more oil in the melody” (instruction to a student whose cantilena sounds dry and faded). “The sensation is approximately the same as if something is shaken out of the sleeve” (regarding the chord technique in one of the fragments of Liszt’s “Mephisto-Waltz”). Or, finally, meaningful: “It is not necessary that all emotions splash out – leave something inside …”

Characteristically: after Flier’s fine-tuning, any piece that was sufficiently solidly and soundly worked out by a student acquired a special pianistic impressiveness and elegance that was not characteristic of it before. He was an unsurpassed master of bringing brilliance to the game of students. “A student’s work is boring in the classroom – it will look even more boring on stage,” Yakov Vladimirovich stated. Therefore, the performance in the lesson, he believed, should be as close as possible to the concert, become a kind of stage double. That is, even in advance, in laboratory conditions, it is necessary to encourage such an important quality as artistry in a young pianist. Otherwise, the teacher, when planning a public performance of his pet, will be able to rely only on random luck.

One more thing. It is no secret that any audience is always impressed by the courage of the performer on the stage. On this occasion, Flier noted the following: “Being at the keyboard, one should not be afraid to take risks – especially in young years. It is important to develop stage courage in yourself. Moreover, a purely psychological moment is still hidden here: when a person is overly cautious, cautiously approaches one or another difficult place, a “treacherous” leap, etc., this difficult place, as a rule, does not come out, breaks down … ”This is – in theory. In fact, nothing inspired Flier’s pupils to stage fearlessness so much as the playful manner of their teacher, well known to them.

… In the autumn of 1959, unexpectedly for many, posters announced the return of Flier to the big concert stage. Behind was a difficult operation, long months of restoration of pianistic technique, getting into shape. Again, after a break of more than ten years, Flier leads the life of a guest performer: he plays in various cities of the USSR, travels abroad. He is applauded, greeted with warmth and cordiality. As an artist, he generally remains true to himself. For all that, another master, another Flier, came into the concert life of the sixties…

“Over the years, you begin to perceive art somehow differently, this is inevitable,” he said in his declining years. “Views of music change, their own aesthetic concepts change. Much is presented almost in the opposite light than in youth … Naturally, the game becomes different. This, of course, does not mean that everything now necessarily turns out to be more interesting than before. Maybe something sounded more interesting just in the early years. But the fact is the fact – the game becomes different … “

Indeed, listeners immediately noticed how much Flier’s art had changed. In his very appearance on the stage, a great depth, inner concentration appeared. He became calmer and more balanced behind the instrument; accordingly, more restrained in the manifestation of feelings. Both temperament and poetic impulsivity began to be taken under clear control by him.

Perhaps his performance was somewhat diminished by the spontaneity with which he charmed pre-war audiences. But the obvious emotional exaggerations have also decreased. Both the sonic surges and the volcanic explosions of climaxes were not as spontaneous with him as before; one got the impression that they were now carefully thought out, prepared, polished.

This was especially felt in Flier’s interpretation of Ravel’s “Choreographic Waltz” (by the way, he made an arrangement of this work for the piano). It was also noticed in Bach-Liszt’s Fantasia and Fugue in G minor, Mozart’s C minor sonata, Beethoven’s Seventeenth Sonata, Schumann’s Symphonic Etudes, Chopin’s scherzos, mazurkas and nocturnes, Brahms’ B minor rhapsody and other works that were part of the pianist’s repertoire of recent years.

Everywhere, with particular force, his heightened sense of proportion, the artistic proportion of the work, began to manifest itself. There was strictness, sometimes even some restraint in the use of colorful and visual techniques and means.

The aesthetic result of all this evolution was a special enlargement of poetic images in Flier. The time has come for inner harmony of feelings and forms of their stage expression.

No, Flier did not degenerate into an “academician”, he did not change his artistic nature. Until his last days, he performed under the dear and close to him flag of romanticism. His romanticism only became different: mature, in-depth, enriched by a long life and creative experience …

G. Tsypin