Some features of Beethoven’s piano sonatas

Contents

Beethoven, a great maestro, a master of the sonata form, throughout his life searched for new facets of this genre, fresh ways to embody his ideas in it.

The composer remained faithful to the classical canons until the end of his life, but in his search for a new sound he often went beyond the boundaries of style, finding himself on the verge of discovering a new, yet unknown romanticism. Beethoven’s genius was that he took the classical sonata to the pinnacle of perfection and opened a window into a new world of composition.

Unusual examples of Beethoven’s interpretation of the sonata cycle

Choking within the framework of the sonata form, the composer increasingly tried to move away from the traditional formation and structure of the sonata cycle.

This can be seen already in the Second Sonata, where instead of a minuet he introduces a scherzo, which he will do more than once. He widely uses genres unconventional for sonatas:

- march: in sonatas No. 10, 12 and 28;

- instrumental recitatives: in Sonata No. 17;

- arioso: in Sonata №31.

He interprets the sonata cycle itself very freely. Freely handling the traditions of alternating slow and fast movements, he begins with slow music Sonata No. 13, “Moonlight Sonata” No. 14. In Sonata No. 21, the so-called “Aurora” (some Beethoven sonatas have titles), the final movement is preceded by a kind of introduction or introduction that serves as the second movement. We observe the presence of a kind of slow overture in the first movement of Sonata No. 17.

Beethoven was also not satisfied with the traditional number of parts in a sonata cycle. His sonatas Nos. 19, 20, 22, 24, 27, and 32 are two-movement; more than ten sonatas have a four-movement structure.

Sonatas No. 13 and No. 14 do not have a single sonata allegro as such.

Variations in Beethoven’s piano sonatas

Composer L. Beethoven

An important place in Beethoven’s sonata masterpieces is occupied by parts interpreted in the form of variations. In general, the variation technique, variation as such, was widely used in his work. Over the years, it acquired greater freedom and became different from the classical variations.

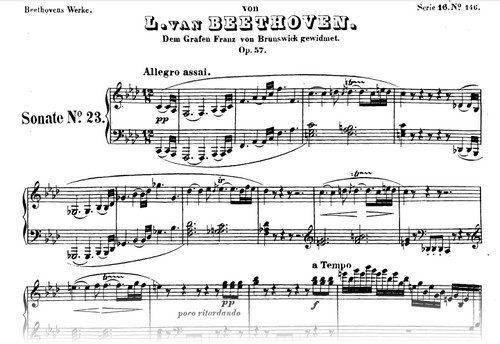

The first movement of Sonata No. 12 is an excellent example of variations in the composition of sonata form. For all its laconicism, this music expresses a wide range of emotions and states. No other form than variations could express the pastoral and contemplative nature of this beautiful piece so gracefully and sincerely.

The author himself called the state of this part “thoughtful reverence.” These thoughts of a dreamy soul caught in the lap of nature are deeply autobiographical. An attempt to escape from painful thoughts and immerse yourself in the contemplation of the beautiful surroundings always ends in the return of even darker thoughts. It is not for nothing that these variations are followed by a funeral march. Variability in this case is brilliantly used as a way of observing internal struggle.

The second part of the “Appassionata” is also full of such “reflections within oneself.” It is no coincidence that some variations sound in the low register, plunging into dark thoughts, and then soar into the upper register, expressing the warmth of hope. The variability of the music conveys the instability of the hero’s mood.

The finales of sonatas No. 30 and No. 32 were also written in the form of variations. The music of these parts is permeated with dreamy memories; it is not effective, but contemplative. Their themes are emphatically soulful and reverent; they are not acutely emotional, but rather restrainedly melodious, like memories through the prism of past years. Each variation transforms the image of a passing dream. In the hero’s heart there is either hope, then the desire to fight, giving way to despair, then again the return of the dream image.

Fugues in Beethoven’s late sonatas

Beethoven enriches his variations with a new principle of a polyphonic approach to composition. Beethoven was so inspired by polyphonic composition that he introduced it more and more. Polyphony serves as an integral part of the development in Sonata No. 28, the finale of Sonatas No. 29 and 31.

In the later years of his creative work, Beethoven outlined the central philosophical idea that runs through all his works: the interconnection and interpenetration of contrasts into each other. The idea of the conflict between good and evil, light and darkness, which was so vividly and violently reflected in the middle years, is transformed by the end of his work into the deep thought that victory in trials comes not in heroic battle, but through rethinking and spiritual strength.

Therefore, in his later sonatas he comes to the fugue as the crown of dramatic development. He finally realized that he could become the result of music that was so dramatic and mournful that even life could not continue. Fugue is the only possible option. This is how G. Neuhaus spoke about the final fugue of Sonata No. 29.

Watch this video on YouTube

After suffering and shock, when the last hope fades away, there are no emotions or feelings, only the ability to think remains. Cold, sober reason embodied in polyphony. On the other hand, there is an appeal to religion and unity with God.

It would be completely inappropriate to end such music with a cheerful rondo or calm variations. This would be a blatant discrepancy with its entire concept.

The fugue of the finale of Sonata No. 30 was a complete nightmare for the performer. It is huge, two-themed and very complex. By creating this fugue, the composer tried to embody the idea of the triumph of reason over emotions. There really are no strong emotions in it, the development of the music is ascetic and thoughtful.

Sonata No. 31 also ends with a polyphonic finale. However, here, after a purely polyphonic fugue episode, the homophonic structure of the texture returns, which suggests that the emotional and rational principles in our life are equal.