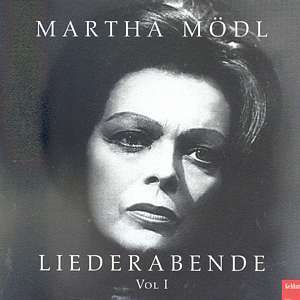

Martha Mödl (Martha Mödl) |

Martha Mödl

“Why do I need another tree on the stage, if I have Mrs. X!”, – such a remark from the director’s lips in relation to the debutante would hardly inspire the latter. But in our story, which took place in 1951, the director was Wieland Wagner, and Mrs X was his lucky find, Martha Mödl. Defending the legitimacy of the style of the new Bayreuth, based on the rethinking and “deromanticization” of the myth, and tired of the endless citations of the “Old Man” * (“Kinder, schafft Neues!”), W. Wagner launched an argument with a “tree”, reflecting his new approach to stage design for opera productions.

The first post-war season was opened by an empty stage of Parsifal, cleared of animal skins, horned helmets and other pseudo-realistic paraphernalia, which, moreover, could evoke unwanted historical associations. It was filled with light and a team of talented young singer-actors (Mödl, Weber, Windgassen, Uhde, London). In March Mödl, Wieland Wagner found a soul mate. The image of Kundry she created, “in the charm of whose humanity (in Nabokov’s way) there was an expressive renewal of her unearthly essence,” became a kind of manifesto for his revolution, and Mödl became the prototype of a new generation of singers.

With all the attention and respect for the accuracy of intonation, she always emphasized the paramount importance for her of revealing the dramatic potential of the operatic role. A born dramatic actress (“Northern Callas”), passionate and intense, she sometimes did not spare her voice, but her breathtaking interpretations made her forget about technology altogether and mesmerized even the most captious critics. It is no coincidence that Furtwängler enthusiastically dubbed her “Zauberkasten”. “Sorceress”, we would say. And if not a sorceress, then how could this amazing woman remain in demand by the opera houses of the world even on the threshold of the third millennium? ..

She was born in Nuremberg in 1912. She studied at the school of English maids of honor, played the piano, was the first student in the ballet class and the owner of a beautiful viola, staged by nature. Pretty soon, however, all this had to be forgotten. Martha’s father – a Bohemian artist, a gifted man and dearly loved by her – one fine day disappeared in an unknown direction, leaving his wife and daughter in need and loneliness. The struggle for survival has begun. After leaving school, Marta began to work – first as a secretary, then as an accountant, collecting forces and funds in order to at least someday get the opportunity to sing. She almost never and nowhere remembers the Nuremberg period of her life. On the streets of the legendary city of Albrecht Dürer and the poet Hans Sachs, in the vicinity of the monastery of St. Catherine, where the famous Meistersinger competitions once took place, in the years of Martha Mödl’s youth, the first bonfires were lit, into which the books of Heine, Tolstoy, Rolland and Feuchtwanger were thrown. The “New Meistersingers” turned Nuremberg into a Nazi “Mecca”, holding their processions, parades, “torch trains” and “Reichspartertags” in it, on which the Nuremberg “racial” and other crazy laws were developed …

Now let’s listen to her Kundry at the beginning of the 2nd act (live recording of 1951) – Ach! — Ah! Tiefe Nacht! — Wahnsinn! -O! -Wut!-Ach!- Jammer! — Schlaf-Schlaf — tiefer Schlaf! – Tod! .. God knows what experiences these terrible intonations were born from … Eyewitnesses of the performance had their hair on end, and other singers, at least for the next decade, refrained from playing this role.

Life seems to start all over again in Remscheid, where Martha, having barely had time to start her long-awaited study at the Nuremberg Conservatory, arrives for an audition in 1942. “They were looking for a mezzo in the theater … I sang half of Eboli’s aria and was accepted! I remember how I later sat in a cafe near the Opera, looked out the huge window at passers-by running past … It seemed to me that Remscheid was the Met, and now I worked there … What a happiness it was!

Shortly after Mödl (at 31) made her debut as Hansel in Humperdinck’s opera, the theater building was bombed. They continued to rehearse in a temporarily adapted gym, Cherubino, Azucena and Mignon appeared in her repertoire. Performances were now given not every evening, for fear of raids. During the day, theater artists were forced to work for the front – otherwise the fees were not paid. Mödl recalled: “They came to get a job at the Alexanderwerk, a factory that produced kitchen utensils before the war, and now ammunition. The secretary, who stamped our passports, when she found out that we were opera artists, said contentedly: “Well, thank God, they finally made the lazy ones work!” This factory had to work for 7 months. The raids became more frequent every day, at any moment everything could fly into the air. Russian prisoners of war were also brought here … A Russian woman and her five children worked with me … the youngest was only four years old, he lubricated parts for shells with oil … my mother was forced to beg because they fed them soup from rotten vegetables – the matron took all the food for herself and feasted with German soldiers in the evenings. I will never forget this.”

The war was coming to an end, and Martha went to “conquer” Düsseldorf. In her hands was a contract for the place of the first mezzo, concluded with the intendant of the Düsseldorf Opera after one of the performances of Mignon in the Remscheid gym. But while the young singer reached the city on foot, along the longest bridge in Europe – Müngstener Brücke – the “thousand-year-old Reich” ceased to exist, and in the theater, almost destroyed to the ground, she was met by a new quartermaster – it was the famous communist and anti-fascist Wolfgang Langoff, the author of Moorsoldaten, who had just returned from Swiss exile. Martha handed him a contract drawn up in a previous era and timidly asked if it was valid. “Of course it works!” Langoff replied.

The real work began with the arrival of Gustav Grundens in the theater. A talented director of the drama theater, he wholeheartedly loved opera, then staged The Marriage of Figaro, Butterfly and Carmen – the main role in the latter was entrusted to Mödl. At Grundens, she went through an excellent acting school. “He worked as an actor, and Le Figaro may have had more Beaumarchais than Mozart (my Cherubino was a huge success!), but he loved music like no other modern director – that’s where all their mistakes come from.”

From 1945 to 1947, the singer sang in Düsseldorf the parts of Dorabella, Octavian and the Composer (Ariadne auf Naxos), later more dramatic parts appeared in the repertoire, such as Eboli, Clytemnestra and Maria (Wozzeck). In the 49th-50s. she was invited to Covent Garden, where she performed Carmen in the main cast in English. The singer’s favorite comment about this performance was this – “imagine – a German woman had the endurance to interpret the Andalusian tigress in the language of Shakespeare!”

An important milestone was the collaboration with director Rennert in Hamburg. There, the singer sang Leonora for the first time, and after performing the role of Lady Macbeth as part of the Hamburg Opera, Marthe Mödl was talked about as a dramatic soprano, which by that time had already become a rarity. For Martha herself, this was only a confirmation of what her conservatory teacher, Frau Klink-Schneider, had once noticed. She always said that the voice of this girl was a mystery to her, “it has more colors than a rainbow, every day it sounds different, and I can’t put it in any particular category!” The transition could therefore be carried out gradually. “I felt that my “do” and passages in the upper register were becoming stronger and more confident … Unlike other singers who always took a break, moving from mezzo to soprano, I did not stop …” In 1950, she tried herself in “Consule” Menotti (Magda Sorel), and after that as Kundry – first in Berlin with Keilbert, then in La Scala with Furtwängler. There was only one step left before the historic meeting with Wieland Wagner and Bayreuth.

Wieland Wagner was then urgently looking for a singer for the role of Kundry for the first post-war festival. He met the name of Martha Mödl in the newspapers in connection with her appearances in Carmen and Consul, but he saw it for the first time in Hamburg. In this thin, cat-eyed, surprisingly artistic and terribly cold Venus (Tannhäuser), who swallowed a hot lemon drink in the overture, the director saw exactly the Kundry he was looking for – earthly and humane. Martha agreed to come to Bayreuth for an audition. “I was almost not worried at all – I had already played this role before, I had all the sounds in place, I didn’t think about success in these first years on stage and there was nothing special to worry about. Yes, and I knew practically nothing about Bayreuth, except that it was a famous festival … I remember that it was winter and the building was not heated, it was terribly cold … Someone accompanied me on a detuned piano, but I was so sure of myself that even that didn’t bother me… Wagner was sitting in the auditorium. When I finished, he said only one phrase – “You are accepted.”

“Kundry opened all the doors for me,” Martha Mödl later recalled. For almost twenty subsequent years, her life was inextricably linked with Bayreuth, which became her summer home. In 1952 she performed as Isolde with Karajan and a year later as Brunnhilde. Martha Mödl also showed highly innovative and ideal interpretations of Wagnerian heroines far beyond Bayreuth – in Italy and England, Austria and America, finally freeing them from the stamp of the “Third Reich”. She was called the “world ambassador” of Richard Wagner (to a certain extent, Wieland Wagner’s original tactics also contributed to this – all new productions were “tried on” by him for singers during tour performances – for example, the San Carlo Theater in Naples became Brünnhilde’s “fitting room”.)

In addition to Wagner, one of the most important roles of the singer’s soprano period was Leonora in Fidelio. Debuting with Rennert in Hamburg, she later sang it with Karajan at La Scala and in 1953 with Furtwängler in Vienna, but her most memorable and moving performance was at the historic opening of the restored Vienna State Opera on November 5, 1955.

Almost 20 years given to big Wagnerian roles could not but affect Martha’s voice. In the mid-60s, tension in the upper register became more and more noticeable, and with the performance of the role of the Nurse at the Munich gala premiere of “Women Without a Shadow” (1963), she began a gradual return to the repertoire of mezzo and contralto. This was a return by no means under the sign of “surrendering positions.” With triumphant success she sang Clytemnestra with Karajan at the Salzburg Festival in 1964-65. In her interpretation, Clytemnestra appears unexpectedly not as a villain, but as a weak, desperate and deeply suffering woman. The Nurse and Clytemnestra are firmly in her repertoire, and in the 70s she performed them at Covent Garden with the Bavarian Opera.

In 1966-67, Martha Mödl says goodbye to Bayreuth, performing Waltrauta and Frikka (it is unlikely that there will be a singer in the history of the Ring who performed 3 Brunhilde, Sieglinde, Waltrauta and Frikka!). Leaving the theater altogether seemed to her, however, unthinkable. She said goodbye forever to Wagner and Strauss, but there was so much other interesting work ahead that suited her like no one else in terms of age, experience, and temperament. In the “mature period” of creativity, the talent of Martha Mödl, a singing actress, is revealed with renewed vigor in dramatic and character parts. “Ceremonial” roles are Grandmother Buryya in Janacek’s Enufa (critics noted the purest intonation, despite the strong vibrato!), Leokadiya Begbik in Weil’s The Rise and Fall of the City of Mahagonny, Gertrud in Marschner’s Hans Heiling.

Thanks to the talent and enthusiasm of this artist, many operas by contemporary composers have become popular and repertoire – “Elizabeth Tudor” by V. Fortner (1972, Berlin, premiere), “Deceit and Love” by G. Einem (1976, Vienna, premiere), “Baal” F. Cherhi (1981, Salzburg, premiere), A. Reimann’s “Ghost Sonata” (1984, Berlin, premiere) and a number of others. Even the small parts assigned to Mödl became central thanks to her magical stage presence. So, for example, in 2000, the performances of “Sonata of Ghosts”, where she played the role of the Mummy, ended not just with a standing ovation – the audience rushed to the stage, hugged and kissed this living legend. In 1992, in the role of the Countess (“Queen of Spades”) Mödl, solemnly said goodbye to the Vienna Opera. In 1997, having heard that E. Söderström, at the age of 70, decided to interrupt her well-deserved rest and perform the Countess at the Met, Mödl jokingly remarked: “Söderström? She is too young for this role! ”, And in May 1999, unexpectedly rejuvenated as a result of a successful operation that made it possible to forget about chronic myopia, Countess-Mödl, at the age of 87, again takes the stage in Mannheim! At that time, her active repertoire also included two “nannies” – in “Boris Godunov” (“Komishe Oper”) and in “Three Sisters” by Eötvös (Düsseldorf premiere), as well as a role in the musical “Anatevka”.

In one of the later interviews, the singer said: “Once the father of Wolfgang Windgassen, the famous tenor himself, told me:“ Martha, if 50 percent of the public loves you, consider that you have taken place. And he was absolutely right. Everything that I have achieved over the years, I owe only to the love of my audience. Please write it. And be sure to write that this love is mutual! ”…

Marina Demina

Note: * “The Old Man” – Richard Wagner.