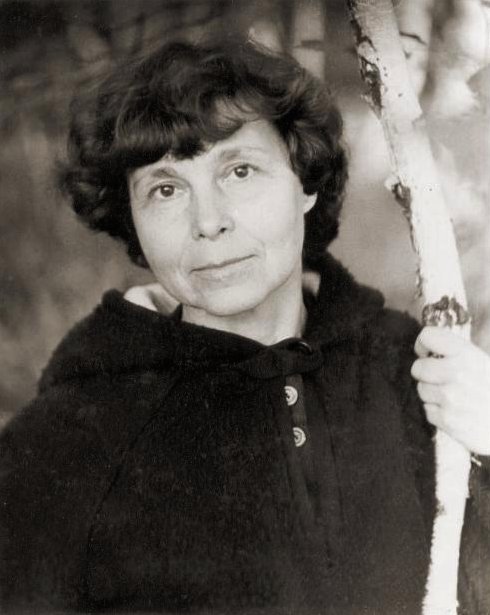

Sofia Asgatovna Gubaidulina (Sofia Gubaidulina) |

Sofia Gubaidulina

At that hour, soul, poems Worlds wherever you want To reign, — a palace of souls, Soul, poems. M. Tsvetaeva

S. Gubaidulina is one of the most significant Soviet composers of the second half of the XNUMXth century. Her music is characterized by great emotional power, a large line of development and, at the same time, the subtlest sense of the expressiveness of sound – the nature of its timbre, performing technique.

One of the important tasks set by S. A. Gubaidulina is to synthesize the features of the culture of the West and the East. This is facilitated by her origin from a Russian-Tatar family, life first in Tataria, then in Moscow. Belonging neither to “avant-gardism”, nor to “minimalism”, nor to the “new folklore wave” or any other modern trend, she has a bright individual style of her own.

Gubaidulina is the author of dozens of works in various genres. Vocal opuses run through all her work: the early “Facelia” based on the poem by M. Prishvin (1956); cantatas “Night in Memphis” (1968) and “Rubaiyat” (1969) on st. oriental poets; the oratorio “Laudatio pacis” (on the station of J. Comenius, in collaboration with M. Kopelent and P. X. Dietrich – 1975); “Perception” for soloists and string ensemble (1983); “Dedication to Marina Tsvetaeva” for choir a cappella (1984) and others.

The most extensive group of chamber compositions: Piano Sonata (1965); Five studies for harp, double bass and percussion (1965); “Concordanza” for ensemble of instruments (1971); 3 string quartets (1971, 1987, 1987); “Music for harpsichord and percussion instruments from the collection of Mark Pekarsky” (1972); “Detto-II” for cello and 13 instruments (1972); Ten Etudes (Preludes) for cello solo (1974); Concerto for bassoon and low strings (1975); “Light and Dark” for organ (1976); “Detto-I” – Sonata for organ and percussion (1978); “De prolundis” for button accordion (1978), “Jubilation” for four percussionists (1979), “In croce” for cello and organ (1979); “In the beginning there was rhythm” for 7 drummers (1984); “Quasi hoketus” for piano, viola and bassoon (1984) and others.

The area of symphonic works by Gubaidulina includes “Steps” for orchestra (1972); “Hour of the Soul” for solo percussion, mezzo-soprano and symphony orchestra at st. Marina Tsvetaeva (1976); Concerto for two orchestras, variety and symphony (1976); concertos for piano (1978) and violin and orchestra (1980); The symphony “Stimmen… Verftummen…” (“I Hear… It Has Been Silent…” – 1986) and others. One composition is purely electronic, “Vivente – non vivante” (1970). The music of Gubaidulina for cinema is significant: “Mowgli”, “Balagan” (cartoons), “Vertical”, “Department”, “Smerch”, “Scarecrow”, etc. Gubaidulina graduated from the Kazan Conservatory in 1954 as a pianist (with G. Kogan ), studied optionally in composition with A. Lehman. As a composer, she graduated from the Moscow Conservatory (1959, with N. Peiko) and graduate school (1963, with V. Shebalin). Wanting to devote herself only to creativity, she chose the path of a free artist for the rest of her life.

Creativity Gubaidulina was relatively little known during the period of “stagnation”, and only perestroika brought him wide recognition. The works of the Soviet master received the highest appraisal abroad. Thus, during the Boston Festival of Soviet Music (1988), one of the articles was titled: “The West Discovers the Genius of Sofia Gubaidulina.”

Among the performers of music by Gubaidulina are the most famous musicians: conductor G. Rozhdestvensky, violinist G. Kremer, cellists V. Tonkha and I. Monighetti, bassoonist V. Popov, bayan player F. Lips, percussionist M. Pekarsky and others.

Gubaidulina’s individual composing style took shape in the mid-60s, starting with Five Etudes for harp, double bass and percussion, filled with the spiritual sound of an unconventional ensemble of instruments. This was followed by 2 cantatas, thematically addressed to the East – “Night in Memphis” (on texts from ancient Egyptian lyrics translated by A. Akhmatova and V. Potapova) and “Rubaiyat” (on verses by Khaqani, Hafiz, Khayyam). Both cantatas reveal the eternal human themes of love, sorrow, loneliness, consolation. In music, elements of oriental melismatic melody are synthesized with western effective dramaturgy, with dodecaphonic composing technique.

In the 70s, not carried away by either the “new simplicity” style that was widely spread in Europe, or the method of polystylistics, which was actively used by the leading composers of her generation (A. Schnittke, R. Shchedrin, etc.), Gubaidulina continued to search for areas of sound expressiveness (for example, in Ten Etudes for Cello) and musical dramaturgy. The concerto for bassoon and low strings is a sharp “theatrical” dialogue between the “hero” (a solo bassoon) and the “crowd” (a group of cellos and double basses). At the same time, their conflict is shown, which goes through various stages of mutual misunderstanding: the “crowd” imposing its position on the “hero” – the internal struggle of the “hero” – his “concessions to the crowd” and the moral fiasco of the main “character”.

“Hour of the Soul” for solo percussion, mezzo-soprano and orchestra contains the opposition of the human, lyrical and aggressive, inhuman principles; the result is an inspired lyrical vocal finale to the sublime, “Atlantean” verses of M. Tsvetaeva. In the works of Gubaidulina, a symbolic interpretation of the original contrasting pairs appeared: “Light and Dark” for the organ, “Vivente – non vivente”. (“Living – inanimate”) for electronic synthesizer, “In croce” (“Crosswise”) for cello and organ (2 instruments exchange their themes in the course of development). In the 80s. Gubaidulina again creates works of a large, large-scale plan, and continues her favorite “oriental” theme, and increases her attention to vocal music.

The Garden of Joy and Sorrow for flute, viola and harp is endowed with a refined oriental flavor. In this composition, the subtle melismatics of the melody is whimsical, the interweaving of high register instruments is exquisite.

The concerto for violin and orchestra, called by the author “Offertorium”, embodies the idea of sacrifice and rebirth to a new life by musical means. The theme from J. S. Bach’s “Musical Offering” in the orchestral arrangement by A. Webern acts as a musical symbol. The third string quartet (single-part) deviates from the tradition of the classical quartet, it is based on the contrast of the “man-made” pizzicato playing and the “not-made” bow playing, which is also given a symbolic meaning.

Gubaidulina considers “Perception” (“Perception”) for soprano, baritone and 7 string instruments in 13 parts to be one of his best works. It arose as a result of correspondence with F. Tanzer, when the poet sent the texts of his poems, and the composer gave both verbal and musical answers to them. This is how the symbolic dialogue between Man and Woman arose on the topics: Creator, Creation, Creativity, Creature. Gubaidulina achieved here an increased, penetrating expressiveness of the vocal part and used a whole scale of voice techniques instead of ordinary singing: pure singing, aspirated singing, Sprechstimme, pure speech, aspirated speech, intoned speech, whisper. In some numbers, a magnetic tape with a recording of the participants in the performance was added. The lyrical-philosophical dialogue of a Man and a Woman, having gone through the stages of its embodiment in a number of numbers (No. 1 “Look”, No. 2 “We”, No. 9 “I”, No. 10 “I and You”), comes to its culmination in No. 12 “The Death of Monty” This most dramatic part is a ballad about the black horse Monty, who once took prizes at the races, and is now betrayed, sold, beaten, dead. No. 13 “Voices” serves as a dispelling afterword. The opening and closing words of the finale – “Stimmen… Verstummen…” (“Voices… Silenced…”) served as a subtitle for Gubaidulina’s large twelve-movement First Symphony, which continued the artistic ideas of “Perception”.

The path of Gubaidulina in art can be indicated by the words from her cantata “Night in Memphis”: “Do your deeds on earth at the behest of your heart.”

V. Kholopova