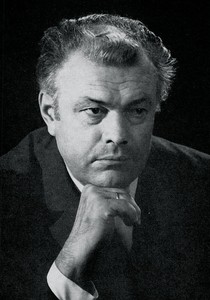

Robert Casadesus |

Robert Casadesus

Over the past century, several generations of musicians bearing the surname Casadesus have multiplied the glory of French culture. Articles and even studies are devoted to many representatives of this family, their names can be found in all encyclopedic publications, in historical works. There is, as a rule, also a mention of the founder of the family tradition – the Catalan guitarist Louis Casadesus, who moved to France in the middle of the last century, married a Frenchwoman and settled in Paris. Here, in 1870, his first son Francois Louis was born, who achieved considerable fame as a composer and conductor, publicist and musical figure; he was the director of one of the Parisian opera houses and the founder of the so-called American Conservatory in Fontainebleau, where talented young people from across the ocean studied. Following him, his younger brothers achieved recognition: Henri, an outstanding violist, promoter of early music (he also played brilliantly on the viola d’amour), Marius the violinist, a virtuoso of playing the rare quinton instrument; at the same time in France they recognized the third brother – cellist Lucien Casadesus and his wife – pianist Rosie Casadesus. But the true pride of the family and of all French culture is, of course, the work of Robert Casadesus, the nephew of the three musicians mentioned. In his person, France and the whole world honored one of the outstanding pianists of our century, who personified the best and most typical aspects of the French school of piano playing.

- Piano music in the Ozon online store →

From what has been said above, it is clear in what atmosphere permeated with music Robert Casadesus grew up and was brought up. Already at the age of 13, he became a student at the Paris Conservatory. Studying piano (with L. Diemaire) and composition (with C. Leroux, N. Gallon), a year after admission, he received a prize for performing the Theme with Variations by G. Fauré, and by the time he graduated from the conservatory (in 1921 ) was the owner of two more higher distinctions. In the same year, the pianist went on his first tour of Europe and very quickly rose to prominence on the world pianistic horizon. At the same time, the friendship of Casadesus with Maurice Ravel was born, which lasted until the end of the life of the great composer, as well as with Albert Roussel. All this contributed to the early formation of his style, gave a clear and clear direction to his development.

Twice in the pre-war years – 1929 and 1936 – the French pianist toured the USSR, and his performing image of those years received a versatile, although not entirely unanimous assessment of critics. Here is what G. Kogan wrote then: “His performance is always imbued with the desire to reveal and convey the poetic content of the work. His great and free virtuosity never turns into an end in itself, always obeys the idea of interpretation. But the individual strength of Casadesus and the secret of his enormous success with us … lies in the fact that artistic principles, which have become a dead tradition among others, retain in him – if not completely, then to a large extent – their immediacy, freshness and effectiveness … Casadesus is distinguished by the absence spontaneity, regularity and somewhat rational clarity of interpretation, which puts strict limits on his significant temperament, a more detailed and sensual perception of music, leading to some slowness of pace (Beethoven) and to a noticeable degradation of the feeling of a large form, often breaking up in an artist into a number of episodes (Liszt’s sonata) … On the whole, a highly talented artist, who, of course, does not introduce anything new into the European traditions of pianistic interpretation, but belongs to the best representatives of these traditions at the present time.

Paying tribute to Casadesus as a subtle lyricist, a master of phrasing and sound coloring, alien to any external effects, the Soviet press also noted the pianist’s certain inclination towards intimacy and intimacy of expression. Indeed, his interpretations of the works of the Romantics – especially in comparison with the best and closest examples to us – lacked scale, drama, and heroic enthusiasm. However, even then he was rightfully recognized both in our country and in other countries as an excellent interpreter in two areas – the music of Mozart and the French Impressionists. (In this regard, as in regard to the basic creative principles, and indeed artistic evolution, Casadesus has much in common with Walter Gieseking.)

What has been said should by no means be taken to mean that Debussy, Ravel and Mozart formed the foundation of Casadesus’ repertoire. On the contrary, this repertoire was truly immense – from Bach and harpsichordists to contemporary authors, and over the years its boundaries have expanded more and more. And at the same time, the nature of the artist’s art changed noticeably and significantly, moreover, many composers – classics and romantics – gradually opened up for him and for his listeners all new facets. This evolution was especially clearly felt in the last 10-15 years of his concert activity, which did not stop until the end of his life. Over the years, not only life wisdom came, but also a sharpening of feelings, which largely changed the nature of his pianism. The artist’s playing has become more compact, stricter, but at the same time fuller-sounding, brighter, sometimes more dramatic – moderate tempos are suddenly replaced by whirlwinds, contrasts are exposed. This manifested itself even in Haydn and Mozart, but especially in the interpretation of Beethoven, Schumann, Brahms, Liszt, Chopin. This evolution is clearly seen in the recordings of four of the most popular sonatas, Beethoven’s First and Fourth Concertos (released only in the early 70s), as well as several Mozart concertos (with D. Sall), Liszt’s concertos, many of Chopin’s works (including Sonatas in B minor), Schumann’s Symphonic Etudes.

It should be emphasized that such changes took place within the framework of Casadesus’s strong and well-formed personality. They enriched his art, but did not make it fundamentally new. As before – and until the end of days – the hallmarks of Casadesus’s pianism remained the amazing fluency of finger technique, elegance, grace, the ability to perform the most difficult passages and ornaments with absolute accuracy, but at the same time elastic and resilient, without turning rhythmic evenness into monotonous motority. And most of all – his famous “jeu de perle” (literally – “bead game”), which has become a kind of synonym for French piano aesthetics. Like few others, he was able to give life and variety to seemingly completely identical figurations and phrases, for example, in Mozart and Beethoven. And yet – a high culture of sound, constant attention to its individual “color” depending on the nature of the music being performed. It is noteworthy that at one time he gave concerts in Paris, in which he played the works of different authors on different instruments – Beethoven on the Steinway, Schumann on the Bechstein, Ravel on the Erar, Mozart on the Pleyel – thus trying to find for each the most adequate “sound equivalent”.

All of the above makes it possible to understand why the game of Casadesus was alien to any forcedness, rudeness, monotony, any vagueness of constructions, so seductive in the music of the Impressionists and so dangerous in romantic music. Even in the finest sound painting of Debussy and Ravel, his interpretation clearly outlined the construction of the whole, was full-blooded and logically harmonious. To be convinced of this, it is enough to listen to his performance of Ravel’s Concerto for the left hand or Debussy’s preludes, which has been preserved in the recording.

Mozart and Haydn in Casadesus’ later years sounded strong and simple, with virtuoso scope; fast tempos did not interfere with the distinctness of phrasing and melodiousness. Such classics were already not only elegant, but also humane, courageous, inspired, “forgetting about the conventions of court etiquette.” His interpretation of Beethoven’s music attracted with harmony, completeness, and in Schumann and Chopin the pianist was sometimes distinguished by a truly romantic impetuosity. As for the sense of form and logic of development, this is convincingly evidenced by his performance of the Brahms concertos, which also became the cornerstones of the artist’s repertoire. “Someone, perhaps, will argue,” the critic wrote, “that Casadesus is too strict of heart and allows logic to frighten feelings here. But the classical poise of his interpretation, the steadiness of dramatic development, free from any emotional or stylistic extravagances, more than compensates for those moments when poetry is pushed into the background by precise calculation. And this is said about the Second Concerto of Brahms, where, as is well known, any poetry and the loudest pathos are not able to replace the sense of form and dramatic concept, without which the performance of this work inevitably turns into a dreary test for the audience and a complete fiasco for the artist!

But for all that, the music of Mozart and French composers (not only Debussy and Ravel, but also Fauré, Saint-Saens, Chabrier) most often became the pinnacle of his artistic achievements. With amazing brilliance and intuition, he recreated its colorful richness and variety of moods, its very spirit. No wonder Casadesus was the first to have the honor of recording all the piano works of Debussy and Ravel on records. “French music has had no better ambassador than him,” wrote the musicologist Serge Berthomier.

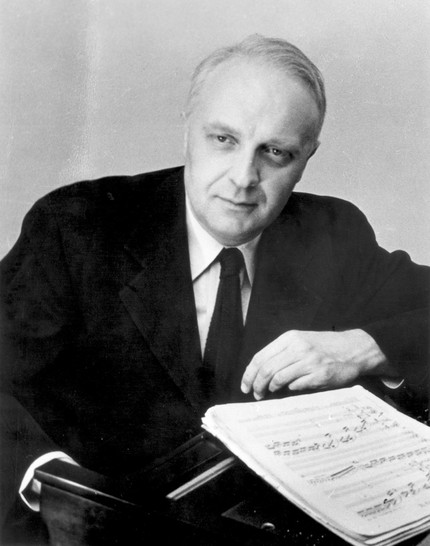

The activity of Robert Casadesus until the end of his days was extremely intense. He was not only an outstanding pianist and teacher, but also a prolific and, according to experts, still underestimated composer. He wrote many piano compositions, often performed by the author, as well as six symphonies, a number of instrumental concertos (for violin, cello, one, two and three pianos with orchestra), chamber ensembles, romances. Since 1935 – since his debut in the USA – Casadesus worked in parallel in Europe and America. In 1940-1946 he lived in the United States, where he established especially close creative contacts with George Sall and the Cleveland Orchestra he led; Later Casadesus’s best recordings were made with this band. During the war years, the artist founded the French Piano School in Cleveland, where many talented pianists studied. In memory of Casadesus’ merits in the development of piano art in the United States, the R. Casadesus Society was established in Cleveland during his lifetime, and since 1975 an international piano competition named after him has been held.

In the post-war years, living now in Paris, now in the USA, he continued to teach the piano class at the American Conservatory of Fontainebleau, founded by his grandfather, and for several years was also its director. Often Casadesus performed in concerts and as an ensemble player; his regular partners were the violinist Zino Francescatti and his wife, the gifted pianist Gaby Casadesus, with whom he performed many piano duets, as well as his own concerto for two pianos. Sometimes they were joined by their son and student Jean, a wonderful pianist, in whom they rightly saw a worthy successor to the musical family of Casadesus. Jean Casadesus (1927-1972) was already famous as a brilliant virtuoso, who was called “the future Gilels”. He led a large independent concert activity and directed his piano class at the same conservatory as his father, when a tragic death in a car accident cut short his career and prevented him from living up to these hopes. Thus the musical dynasty of the Kazadezyus was interrupted.

Grigoriev L., Platek Ya.