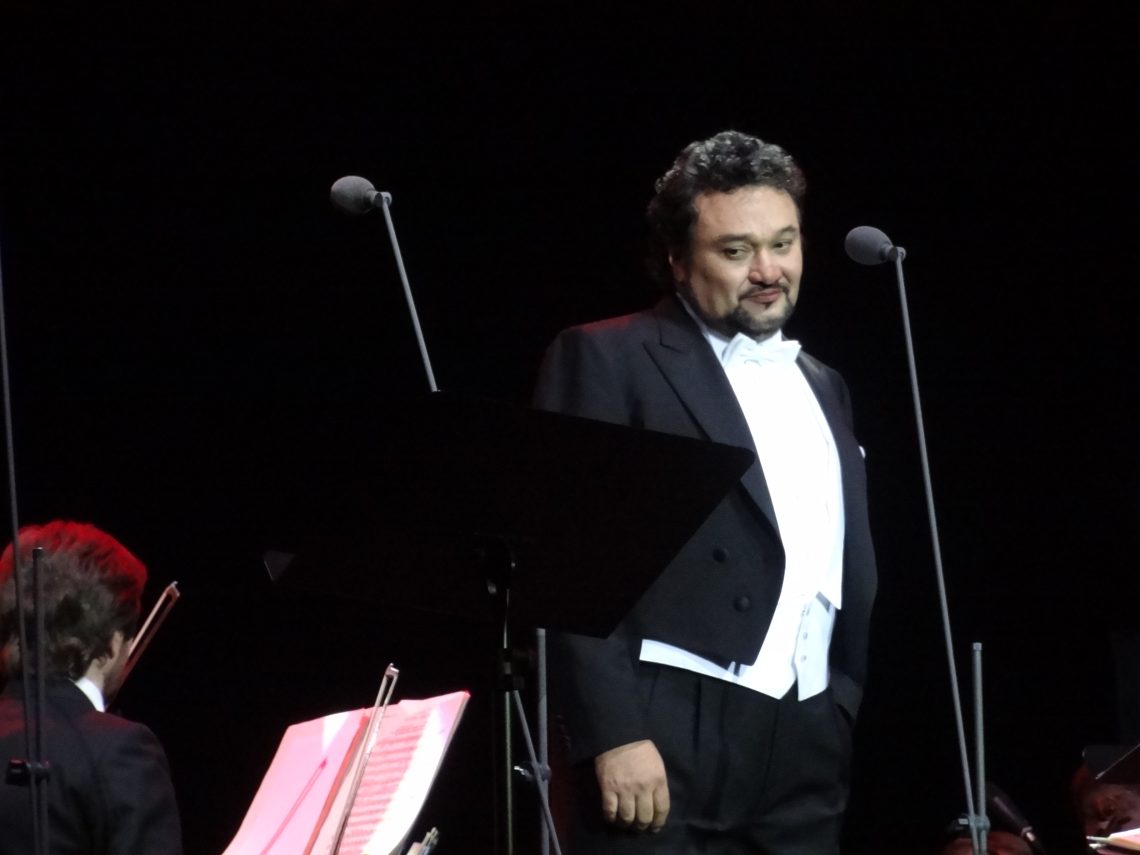

Ramon Vargas |

Ramon Vargas

Ramon Vargas was born in Mexico City and was the seventh in a family of nine children. At the age of nine, he joined the children’s choir of the boys of the Church of the Madonna of Guadalupe. Its musical director was a priest who studied at the Academy of Santa Cecilia. At the age of ten, Vargas made his debut as a soloist at the Theater of Arts. Ramon continued his studies at the Cardinal Miranda Institute of Music, where Antonio Lopez and Ricardo Sanchez were his leaders. In 1982, Ramón makes his Hayden debut at Lo Special, Monterrey, and wins the Carlo Morelli National Vocal Competition. In 1986, the artist won the Enrico Caruso Tenor Competition in Milan. In the same year, Vargas moved to Austria and completed his studies at the vocal school of the Vienna State Opera under the direction of Leo Müller. In 1990, the artist chose the path of a “free artist” and met the famous Rodolfo Celletti in Milan, who is still his vocal teacher to this day. Under his leadership, he performs the main roles in Zurich (“Fra Diavolo”), Marseille (“Lucia di Lammermoor”), Vienna (“Magic Flute”).

In 1992, Vargas made a dizzying international debut: the New York Metropolitan Opera invited a tenor to replace Luciano Pavarotti in Lucia de Lammermoor, along with June Anderson. In 1993 he made his debut at La Scala as Fenton in a new production of Falstaff directed by Giorgio Strehler and Riccardo Muti. In 1994, Vargas got the honorary right to open the season at the Met with the party of the Duke in Rigoletto. Since that time, he has been an adornment of all the main stages – the Metropolitan, La Scala, Covent Garden, Bastille Opera, Colon, Arena di Verona, Real Madrid and many others.

Over the course of his career, Vargas performed more than 50 roles, of which the most significant are: Riccardo in Un ballo in maschera, Manrico in Il trovatore, the title role in Don Carlos, the Duke in Rigoletto, Alfred in La traviata by J. Verdi, Edgardo in “Lucia di Lammermoor” and Nemorino in “Love Potion” by G. Donizetti, Rudolph in “La Boheme” by G. Puccini, Romeo in “Romeo and Juliet” by C. Gounod, Lensky in “Eugene Onegin” by P. Tchaikovsky . Among the outstanding works of the singer are the role of Rudolf in G. Verdi’s opera “Luise Miller”, which he first performed in a new production in Munich, the title paria in “Idomeneo” by W. Mozart at the Salzburg Festival and in Paris; Chevalier de Grieux in “Manon” by J. Massenet, Gabriele Adorno in the opera “Simon Boccanegra” by G. Verdi, Don Ottavio in “Don Giovanni” at the Metropolitan Opera, Hoffmann in “The Tales of Hoffmann” by J. Offenbach at La Scala.

Ramon Vargas actively gives concerts all over the world. His concert repertoire is striking in its versatility – this is a classic Italian song, and a romantic German Lieder, as well as songs by French, Spanish and Mexican composers of the 19th and 20th centuries.

Mexican tenor Ramón Vargas is one of the great young singers of our time, performing successfully on the best stages of the world. More than a decade ago, he participated in the Enrico Caruso Competition in Milan, which became a springboard for him to a brilliant future. It was then that the legendary tenor Giuseppe Di Stefano said of the young Mexican: “Finally we found someone who sings well. Vargas has a relatively small voice, but a bright temperament and excellent technique.

Vargas believes that fortune found him in the Lombard capital. He sings a lot in Italy, which has become his second home. The past year saw him busy with significant productions of Verdi operas: at La Scala Vargas sang in Requiem and Rigoletto with Riccardo Muti, in the United States he performed the role of Don Carlos in the opera of the same name, not to mention Verdi’s music, which he sang in New York. York, Verona and Tokyo. Ramon Vargas is talking to Luigi Di Fronzo.

How did you approach music?

I was about the same age as my son Fernando is now – five and a half. I sang in the children’s choir of the Church of the Madonna of Guadalupe in Mexico City. Our musical director was a priest who studied at the Accademia Santa Cecilia. This is how my musical base was formed: not only in terms of technique, but also in terms of knowledge of styles. We sang mainly Gregorian music, but also polyphonic works from the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, including masterpieces by Mozart and Vivaldi. Some compositions were performed for the first time, such as the Mass of Pope Marcellus Palestrina. It was an extraordinary and very rewarding experience in my life. I ended up making my debut as a soloist at the Arts Theater when I was ten years old.

This is undoubtedly the merit of some teacher …

Yes, I had an exceptional singing teacher, Antonio Lopez. He was very careful about the vocal nature of his students. The exact opposite of what is happening in the United States, where the percentage of singers who manage to launch a career is ludicrous compared to the number who have a voice and study vocals. This is because the educator must encourage the student to follow his specific nature, while violent methods are usually used. The worst of the teachers force you to imitate a certain style of singing. And that means the end.

Some, like Di Stefano, argue that teachers matter little compared to instinct. Do you agree with this?

Basically agree. Because when there is no temperament or a beautiful voice, even a papal blessing cannot make you sing. There are, however, exceptions. The history of the performing arts knows great “made” voices, like Alfredo Kraus, for example (although it must be said that I am a Kraus fan). And, on the other hand, there are artists who are endowed with a pronounced natural talent, like José Carreras, who is the exact opposite of Kraus.

Is it true that in the early years of your success you regularly came to Milan to study with Rodolfo Celletti?

The truth is, a few years ago I took lessons from him and today we sometimes meet. Celletti is a personality and teacher of a huge culture. Smart and great taste.

What lesson did the great singers teach the artists of your generation?

Their sense of drama and naturalness must be revived at all costs. I often think about the lyrical style that distinguished such legendary performers as Caruso and Di Stefano, but also about the sense of theatricality that is now being lost. I ask you to understand me correctly: purity and philological accuracy in relation to the original are very important, but one should not forget about expressive simplicity, which, in the end, gives the most vivid emotions. Unreasonable exaggerations must also be avoided.

You often mention Aureliano Pertile. Why?

Because, although Pertile’s voice was not one of the most beautiful in the world, it was characterized by a purity of sound production and expressiveness, one of a kind. From this point of view, Pertile taught an unforgettable lesson in a style that is not fully understood today. His consistency as an interpreter, a singing devoid of screams and spasms, should be re-evaluated. Pertile followed a tradition that came from the past. He felt closer to Gigli than to Caruso. I am also an ardent admirer of Gigli.

Why are there conductors “suitable” for opera and others less sensitive to the genre?

I do not know, but for the singer this difference plays a big role. Note that a certain type of behavior is also noticeable among some of the audience: when the conductor walks forward, not paying attention to the singer on stage. Or when some of the great conductor’s baton “cover” the voices on stage, demanding from the orchestra too strong and bright sound. There are, however, conductors with whom it is great to work. Names? Muti, Levine and Viotti. Musicians who enjoy if the singer sings well. Enjoying the beautiful top note as if they were playing it with the singer.

What did the Verdi celebrations that took place everywhere in 2001 become for the world of opera?

This is an important moment of collective growth, because Verdi is the backbone of the opera house. Although I adore Puccini, Verdi, from my point of view, is the author who embodies the spirit of melodrama more than anyone else. Not only because of the music, but because of the subtle psychological play between the characters.

How does the perception of the world change when a singer achieves success?

There is a risk of becoming a materialist. To have more and more powerful cars, more and more elegant clothes, real estate in all corners of the world. This risk must be avoided because it is very important not to let money influence you. I’m trying to do charity work. Although I am not a believer, I think that I should return to society what nature has given me with music. In any case, the danger exists. It is important, as the proverb says, not to confuse success with merit.

Could unexpected success compromise a singer’s career?

In a sense, yes, although that is not the real problem. Today, the boundaries of the opera have expanded. Not only because, fortunately, there are no wars or epidemics that force theaters to close and make individual cities and countries inaccessible, but because opera has become an international phenomenon. The trouble is that all the singers want to travel the world without turning down invitations on four continents. Think of the huge difference between what the picture was a hundred years ago and what it is today. But this way of life is hard and difficult. In addition, there were times when cuts were made in operas: two or three arias, a famous duet, an ensemble, and that’s enough. Now they perform everything that is written, if not more.

Do you also like light music…

This is my old passion. Michael Jackson, the Beatles, jazz artists, but especially the music that is created by the people, the lower strata of society. Through it, the people who suffer express themselves.

Interview with Ramon Vargas published in Amadeus magazine in 2002. Publication and translation from Italian by Irina Sorokina.