Quantitative and qualitative value of the interval

Contents

A musical interval is the consonance of two notes and a gap, that is, the distance between them. A detailed acquaintance with intervals, their names and construction principles took place in the last issue. If you need something to refresh your memory, then a link to the previous material will be given below. Today we will continue the study of intervals, and specifically, we will consider two of their very important properties: quantitative and qualitative values.

READ ABOUT INTERVALS HERE

Since interval is the distance between sounds, this distance must be measured somehow. The musical interval has two such dimensions – a quantitative and a qualitative value. What it is? Let’s figure it out.

The quantitative value of the interval

quantitative value says about how many musical steps does an interval cover. Therefore, it is still sometimes called a step value. You are already familiar with this measurement of interval, it is expressed in numbers from 1 to 8, with which intervals are indicated.

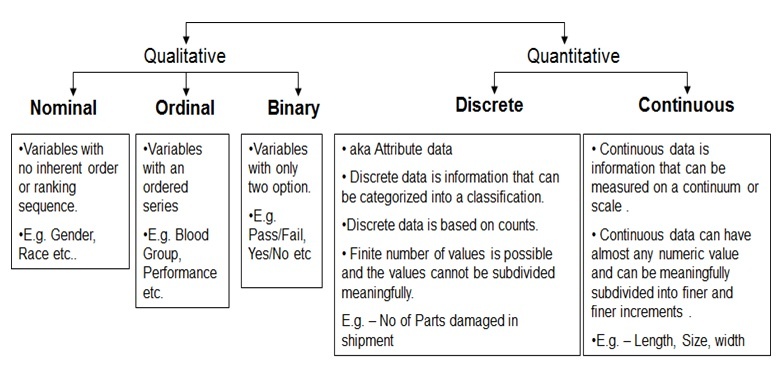

Let’s remember what these mean. number? First, they name the intervals themselves, since the name of the interval is also a number, only in Latin:

Second, these the numbers show how far apart two interval sounds are – lower and upper (base and top). The larger the number, the wider the interval becomes, the farther apart the two sounds that make it up are:

- The number 1 indicates that two sounds are on the same musical level (that is, in fact, prima is the repetition of the same sound twice).

- The number 2 means that the lower sound is on the first step, and the upper sound is on the second (that is, on the next, adjacent sound of the musical ladder). Moreover, the countdown of steps can be started from any sound we need (even from DO, even from PE or from MI, etc.).

- The number 3 means that the base of the interval is on the first step, and the top is on the third of it.

- The number 4 conveys that the distance between notes is 4 steps, and so on.

The principle that we have just described is easier to understand with an example. Let’s build all eight intervals from the PE sound, write them down in notes. You see: with an increase in the number of steps (that is, a quantitative value), the distance, the gap between the base of PE and the second, upper sound of the interval, also increases.

Qualitative value

Qualitative valueand tone value (second name) says how many tones and semitones are in the interval. To understand this, you must first remember what a semitone and a tone are.

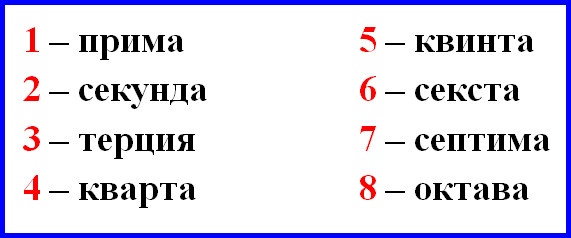

Semitone is the smallest distance between two sounds. It is very convenient to use the piano keyboard for better understanding and greater clarity. The keyboard has black and white keys, and if they are played without gaps, then there will be a semitone distance between two adjacent keys (in sound, of course, and not in location).

For example, from C to C-SHARP, a semitone (a semitone when we went up from a white key to the nearest black one), from C-SHARP to a PE note is also a semitone (when we went down from a black key to the nearest white one). Likewise, from F to F-SHOT and from F-SHOT to G are all examples of semitones.

There are semitones on the piano keyboard, which are formed exclusively by white keys. There are two of them: MI-FA SI and DO, and they need to be remembered.

IMPORTANT! Halftones can be added. And, for example, if you add two semitones (two halves), you get one whole tone (one whole). For example, semitones DO with CSHAR and between CSHAP and PE add up to a whole tone between DO and PE.

To make it easier to add tones, remember the simple rules:

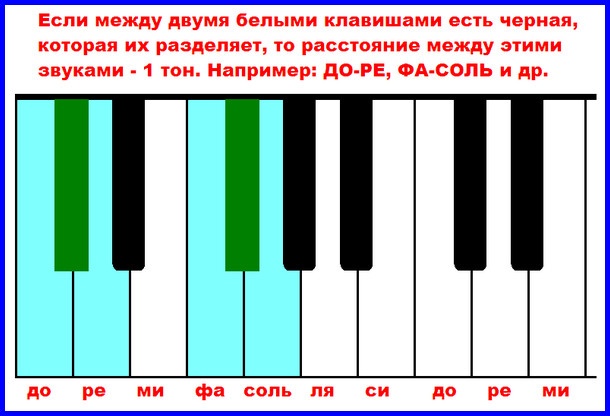

- White color rule. If there is a black key between two adjacent white keys, then the distance between them is 1 whole tone. If there is no black key, then it is a semitone. That is, it turns out: DO-RE, RE-MI, FA-SOL, SOL-LA, LA-SI are whole tones, and MI-FA, SI-DO are semitones.

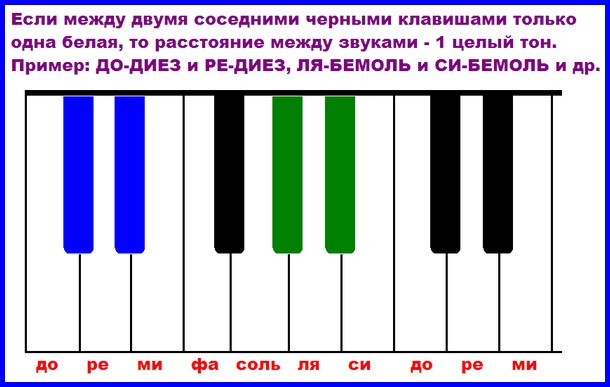

- Black color rule. If two adjacent black keys are separated by only one white key (only one, not two!), then the distance between them is also 1 whole tone. For example: C-SHARP and D-SHARP, F-SHARP and G-SHARP, A-FLAT AND SI-FLAT, etc.

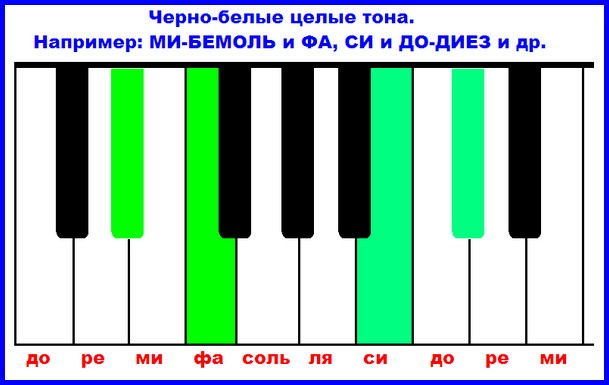

- Black and white rule. In large gaps between black keys, the rule of the cross or the rule of black and white tones applies. So, MI and F-SHARP, as well as MI-FLAT and FA are whole tones. Similarly, whole tones are SI with C-SHARP and SI-Flat with regular C.

For you now, the most important thing is to learn how to add tones, and learn how to determine how many tones or semitones fit from one sound to another. Let’s practice.

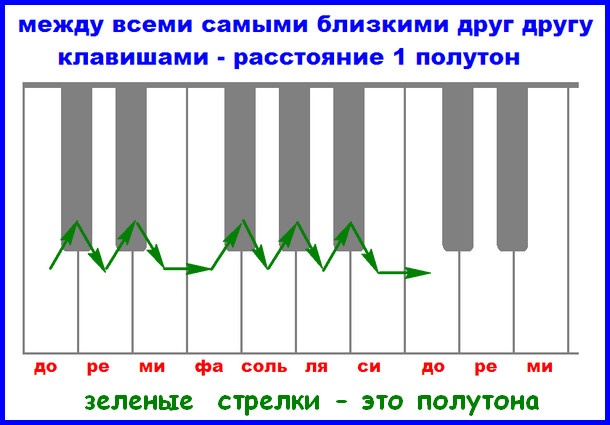

For example, we need to determine how many tones are between the sounds of the sixth D-LA. Both sounds – both do and la, are included in the score. We consider: do-re is 1 tone, then re-mi is another 1 tone, it’s already 2. Further: mi-fa is a semitone, half, add it to the existing 2 tones, we already get 2 and a half tones. The next sounds are fa and salt: another tone, in total already 3 and a half. And the last – salt and la, also a tone. So we got to the note la, and in total we got that from DO to LA there are only 4 and a half tones.

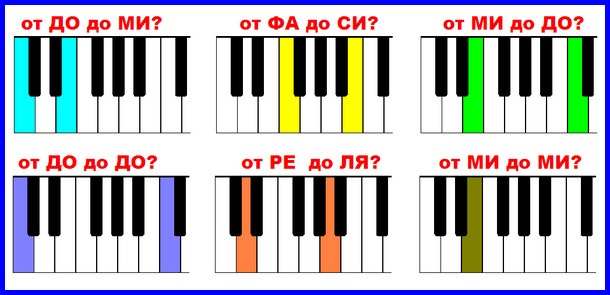

Now let’s do it ourselves! Here are some exercises for you to practice. Count how many tones:

- in thirds DO-MI

- in the FA-SI quarter

- in sexte MI-DO

- in octave DO-DO

- in fifth D-LA

- in the example WE-WE

Well, how? Did you manage? The correct answers are: DO-MI – 2 tones, FA-SI – 3 tones, MI-DO – 4 tones, DO-DO – 6 tones, RE-LA – 3 and a half tones, MI-MI – zero tones. Prima is such an interval in which we do not leave the initial sound, therefore there is no actual distance in it and, accordingly, zero tones.

What is a quality value?

Qualitative value gives new varieties of intervals. Depending on it, the following types of intervals are distinguished:

- Net, there are four of them prima, quarta, fifth and octave. Pure intervals are denoted by a small letter “h”, which is placed in front of the interval number. That is, a pure prima can be abbreviated as ch1, a pure quart – ch4, a fifth – ch5, a pure octave – ch8.

- Small, there are also four of them – this is seconds, thirds, sixths and sevenths. Small intervals are indicated by a small letter “m” (for example: m2, m3, m6, m7).

- Big – they can be the same as small ones, that is second, third, sixth and seventh. Large intervals are denoted by a small letter “b” (b2, b3, b6, b7).

- reduced – they can be any intervals except prima. There is no reduced prima, since there are 0 tones in a pure prima and there is simply nowhere to reduce it (the qualitative value has no negative values). Reduced intervals are abbreviated as “mind” (min2, min3, min4, etc.).

- Increased – you can increase all intervals without exception. The designation is “uv” (uv1, uv2, uv3, etc.).

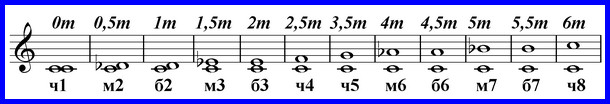

First of all, you need to deal with clean, small and large intervals – they are the main ones. And enlarged and reduced ones will connect to you later. To build a large or small interval, you need to know exactly how many tones are in it. You just need to remember these values (at first, you can write it out on a cheat sheet and constantly look there, but it’s better to learn it right away). So:

Pure prima = 0 tones Minor second = 0,5 tones (half a tone) Major second = 1 tone Minor third = 1,5 tones (one and a half tones) Major third = 2 tones Pure quart = 2,5 tones (two and a half) Pure fifth = 3,5 tones (three and a half) Small sixth u4d XNUMX tones Big sixth u4d 5 tones (four and a half) Small seventh = 5 tones Major seventh = 5,5 tones (five and a half) Pure octave = 6 tones

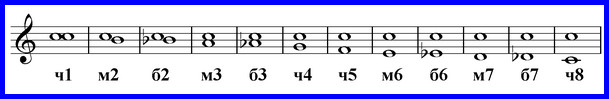

To understand the difference between small and large intervals, watch and play (sing along) the intervals built from the sound to:

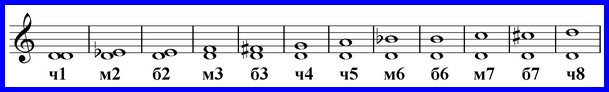

Let’s now put the new knowledge into practice. For example, let’s build all the listed intervals from the sound PE.

- Pure prima from RE is RE-RE. With prima we never have to worry at all, it’s always just the repetition of a sound.

- Seconds are big and small. A second from RE, these are generally the sounds of RE-MI (2 steps). In a small second there should be only half a tone, and in a large second – 1 whole tone. We look at the keyboard, check how many tones from RE to MI: 1 tone, which means that the built second is large. To get a small one, we need to reduce the distance by half a tone. How to do it? We just lower the upper sound by half a tone with the help of a flat. We get: RE and MI-FLAT.

- Terts are also of two types. In general, the third from RE is the sounds of RE-FA. From RE to FA – one and a half tones. What does it say? That this third is small. To get a big one, we need now, on the contrary, to add half a tone. We add this: we increase the upper sound with the help of a sharp. We get: RE and F-SHARP – this is a big third.

- Net quart (ch4). We count four steps from PE, we get PE-SOL. Check how many tones. Should be two and a half. And there is! This means that everything is fine in this quart, there is no need to change anything, no need to add any sharps and flats.

- Perfect fifth. We recall the designation – h5. So, you need to count from PE five steps. These will be the sounds RE and LA. There are three and a half tones between them. Exactly as much as it should be in a normal pure fifth. So, here, too, everything is fine, and no extra signs are required.

- Sexts are small (m6) and large (b6). The six steps from RE are RE-SI. Did you count the tones? From RE to SI – 4 and a half tones, therefore, RE-SI is a sixth big. We make a small one – we lower the upper sound with the help of a flat, thus removing an extra semitone. Now the sixth has become small – RE and SI-FLAT.

- Septims – sevens, there are also two types. The seventh from RE is the sounds of RE-DO. There are five tones between them, that is, we received a small seventh. And to be big – you need to add more. Remember how? With the help of a sharp, we increase the upper sound, add another half tone to make it five and a half. Sounds of the major seventh – RE and C-SHARP.

- A pure octave is another interval with which there are no problems. We repeated the PE at the top, so we got an octave. You can check – it is clean, it has 6 tones.

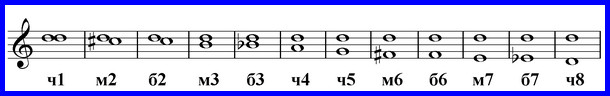

Let’s write out everything that we got on one musical staff:

Here, for example, you also have intervals built from the sound of MI, and only from the rest of the notes – please, try to build it yourself. Do you need to practice? Not all ready-made answers on solfeggio to write off?

And by the way, intervals can be built not only up, but also down. Just in this case, we will need to manipulate the lower sound all the time – if necessary, raise or lower it. How do you know when to raise and when to lower? Look at the keyboard and analyze what is happening: is the distance increasing or decreasing? Is the range widening or narrowing? Well, in accordance with your observations, make the right decision.

If we build the intervals down, then the increase in the lower sound leads to a narrowing of the interval, a decrease in the number of tones-semitones. And the decrease – on the contrary, the interval expands, the quality value increases.

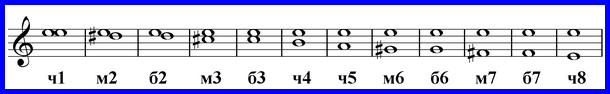

Look, we’ve built the intervals down here from the notes to D and D for you to see. Try to understand:

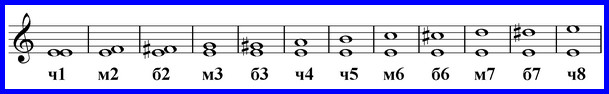

And from MI down, let’s build together, with explanations.

- Pure prima from MI – MI-MI without comment. You can’t build a pure prima either down or up, because it treads on the spot: neither here nor there, it’s the same all the time.

- Seconds: from MI – MI-RE, if you build down. The distance is 1 tone, which means that a second is big. How to make small It is necessary to narrow the interval, remove one semitone, and for this you need to lower the sound (the upper one cannot be changed) to pull it up a little, that is, to raise it with a sharp. We get: MI and D-SHARP – a small second down.

- Thirds. We put aside three steps down (MI-DO), got a big third (2 tones). They pulled the lower sound up half a tone (C-SHARP), got one and a half tones – a small third.

- A perfect fourth and a perfect fifth here are, frankly, normal: MI-SI, MI-LA. If you want – check, count the tones.

- Sextes from MI: MI-SOL is big, isn’t it? Because there are 4 and a half tones in it. To become small, you need to take sol-sharp (something just sharps and sharps, not a single flat – somehow even uninteresting).

- Septima MI-FA is large, and small is MI and FA-SHARP (ugh, sharp again!). And the last, most difficult thing is a pure octave: MI-MI (you will never build it).

Let’s see what happened. Some sharps are continuous, not a single flat. Well at least that’s not always the case. If you build from other notes, then flats can also be found there.

By the way, if you forgot what sharp, flat and bekar are. Well, sometimes it happens… That can be repeated on THIS PAGE.

In order to build and find intervals, to count tones, we often need a piano keyboard in front of our eyes. For convenience, you can print the drawn keyboard, cut it out and put it in your workbook. And you can download the blank for printing from us.

PIANO KEYBOARD PREPARATION – DOWNLOAD

Table of intervals and their values

All the material of this large article can be reduced to one small plate, which we will now show you. You can also redraw this solfeggio cheat sheet in your notebook, somewhere in a conspicuous place, so that you always have it before your eyes.

There will be four columns in the table: the full name of the interval, its short designation, the quantitative value (that is, how many steps are in it) and the qualitative value (how many tones). Don’t get confused? For convenience, you can make yourself an abbreviated version (only the second and last columns).

| Name interval | designation interval | How many steps | How many tones |

| pure prima | ч1 | 1 Art. | 0 item |

| minor second | m2 | 2 Art. | 0,5 item |

| major second | b2 | 2 Art. | 1 item |

| minor third | m3 | 3 Art. | 1,5 item |

| major third | b3 | 3 Art. | 2 item |

| clean quart | ч4 | 4 Art. | 2,5 item |

| perfect fifth | ч5 | 5 Art. | 3,5 item |

| minor sixth | m6 | 6 Art. | 4 item |

| major sixth | b6 | 6 Art. | 4,5 item |

| minor septima | m7 | 7 Art. | 5 item |

| major seventh | b7 | 7 Art. | 5,5 item |

| pure octave | ч8 | 8 Art. | 6 item |

That’s all for now. In the next issues, you will continue the topic “Intervals”, you will learn how to make their conversions, how to get increased and decreased intervals, as well as what newts are and why they live in a music book, and not in the ocean. See you soon!