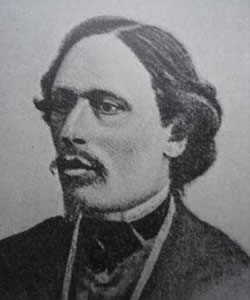

Pierre Gaviniès |

Pierre Gavinies

One of the greatest French violinists of the 1789th century was Pierre Gavignier. Fayol puts him on a par with Corelli, Tartini, Punyani and Viotti, devoting a separate biographical sketch to him. Lionel de la Laurencie devotes a whole chapter to Gavinier in the history of French violin culture. Several biographies were written about him by French researchers of the XNUMXth-XNUMXth centuries. The heightened interest in Gavigne is no accident. He is a very prominent figure in the Enlightenment movement that marked the history of French culture in the second half of the XNUMXth century. Having begun his activity at a time when French absolutism seemed unshakable, Gavignier witnessed its collapse in XNUMX.

A friend of Jean-Jacques Rousseau and a passionate follower of the philosophy of the encyclopedists, whose teachings destroyed the foundations of the nobility’s ideology and contributed to the country’s coming to revolution, Gavignier became a witness and participant in the fierce “fights” in the field of art, which evolved throughout his life from the gallant aristocratic rococo to dramatic operas Gluck and further – to the heroic civil classicism of the revolutionary era. He himself traveled the same path, sensitively responding to everything advanced and progressive. Starting with works of a gallant style, he reached the sentimentalist poetics of the Rousseau type, Gluck’s drama and the heroic elements of classicism. He was also characterized by the rationalism characteristic of the French classicists, which, according to Buquin, “gives a special imprint to music, as an integral part of the general great desire of the era for antiquity.”

Pierre Gavignier was born on May 11, 1728 in Bordeaux. His father, Francois Gavinier, was a talented instrumental maker, and the boy literally grew up among musical instruments. In 1734 the family moved to Paris. Pierre was 6 years old at the time. Who exactly he studied violin with is unknown. The documents only show that in 1741, the 13-year-old Gavignier gave two concerts (the second on September 8) in the Concert Spirituel hall. Lorancey, however, reasonably believes that Gavignier’s musical career began at least a year or two earlier, because an unknown youth would not have been allowed to perform in a famous concert hall. In addition, in the second concert, Gavinier played together with the famous French violinist L. Abbe (son) Leclerc’s Sonata for two violins, which is another evidence of the young musician’s fame. Cartier’s letters contain references to one curious detail: in the first concert, Gavignier made his debut with Locatelli’s caprices and F. Geminiani’s concerto. Cartier claims that the composer, who was in Paris at that time, wished to entrust the performance of this concerto only to Gavignier, despite his youth.

After the 1741 performance, Gavignier’s name disappears from the Concert Spirituel posters until the spring of 1748. Then he gives concerts with great activity up to and including 1753. From 1753 until the spring of 1759, a new break in the concert activity of the violinist follows. A number of his biographers claim that he was forced to leave Paris secretly because of some kind of love story, but, before he had even left for 4 leagues, he was arrested and spent a whole year in prison. Lorancey’s studies do not confirm this story, but they do not refute it either. On the contrary, the mysterious disappearance of a violinist from Paris serves as an indirect confirmation of it. According to Laurency, this could have happened between 1753 and 1759. The first period (1748-1759) brought Gavignier considerable popularity in musical Paris. His partners in performances are such major performers as Pierre Guignon, L. Abbe (son), Jean-Baptiste Dupont, flutist Blavet, singer Mademoiselle Fell, with whom he repeatedly performed Mondonville’s Second Concerto for Violin and Voice with Orchestra. He successfully competes with Gaetano Pugnani, who came to Paris in 1753. At the same time, some critical voices against him were still heard at that time. So, in one of the reviews of 1752, he was advised to “travel” to improve his skills. Gavignier’s new appearance on the concert stage on April 5, 1759 finally confirmed his prominent position among the violinists of France and Europe. From now on, only the most enthusiastic reviews appear about him; he is compared with Leclerc, Punyani, Ferrari; Viotti, after listening to Gavignier’s game, called him “French Tartini”.

His works are also positively evaluated. Incredible popularity, which lasted throughout the second half of the 1759th century, is acquired by his Romance for Violin, which he performed with exceptional penetration. Romance was first mentioned in a review of XNUMX, but already as a play that won the love of the audience: “Monsieur Gavignier performed a concerto of his own composition. The audience listened to him in complete silence and doubled their applause, asking to repeat the Romance. In Gavignier’s work of the initial period there were still many features of the gallant style, but in Romance there was a turn towards that lyrical style that led to sentimentalism and arose as an antithesis of the mannered sensibility of the Rococo.

From 1760, Gavignier began to publish his works. The first of them is the collection “6 Sonatas for Violin Solo with Bass”, dedicated to Baron Lyatan, an officer of the French Guards. Characteristically, instead of the lofty and obsequious stanzas usually adopted in this kind of initiation, Gavignier confines himself to modest and full of hidden dignity in the words: “Something in this work allows me to think with satisfaction that you will accept it as proof of my true feelings for you” . With regard to Gavignier’s writings, critics note his ability to endlessly vary the chosen topic, showing it all in a new and new form.

It is significant that by the 60s the tastes of concert hall visitors were changing dramatically. The former fascination with the “charming arias” of the gallant and sensitive Rococo style is passing away, and a much greater attraction to the lyrics is revealed. In the Concert Spirituel, the organist Balbair performs concertos and numerous arrangements of lyric pieces, while the harpist Hochbrücker performs his own transcription for harp of the lyric minuet Exode, etc. And in this movement from Rococo to sentimentalism of the classicist type, Gavignier occupied far from the last place.

In 1760, Gavinier tries (only once) to compose for the theater. He wrote the music for Riccoboni’s three-act comedy “Imaginary” (“Le Pretendu”). It was written about his music that although it is not new, it is distinguished by energetic ritornellos, depth of feeling in trios and quartets, and piquant variety in arias.

In the early 60s, the remarkable musicians Kaneran, Joliveau and Dovergne were appointed directors of the Concert Spirituel. With their arrival, the activity of this concert institution becomes much more serious. A new genre is steadily developing, destined for a great future – the symphony. At the head of the orchestra are Gavignier, as bandmaster of the first violins, and his student Capron – of the second. The orchestra acquires such flexibility that, according to the Parisian music magazine Mercury, it is no longer necessary to indicate the beginning of each measure with a bow when playing symphonies.

The quoted phrase for the modern reader requires an explanation. From the time of Lully in France, and not only in the opera, but also in the Concert Spirituel, the orchestra was steadfastly controlled by beating the beat with a special staff, the so-called battuta. It survived until the 70s. The conductor in the French opera was called the “batteur de mesure” in French opera. The monotonous clatter of the trampoline resounded through the hall, and the strident Parisians gave the opera conductor the nickname “woodcutter.” By the way, beating time with a battuta caused the death of Lully, who injured his leg with it, which caused blood poisoning. In the Gavignier era, this old form of orchestral leadership was beginning to fade, especially in symphonic conducting. The functions of the conductor, as a rule, began to be performed by an accompanist – a violinist, who indicated the beginning of the bar with a bow. And now the phrase from “Mercury” becomes clear. Trained by Gavignier and Kapron, the orchestra members did not need not only to conduct a battuta, but also to indicate the beat with a bow: the orchestra turned into a perfect ensemble.

In the 60s, Gavinier as a performer is at the zenith of fame. The reviews note the exceptional qualities of his sound, the ease of technical skill. No less appreciated Gavignier and as a composer. Moreover, during this period, he represented the most advanced direction, together with the young Gossec and Duport, paving the way for the classical style in French music.

Gossec, Capron, Duport, Gavignier, Boccherini, and Manfredi, who lived in Paris in 1768, made up a close circle that often met in the salon of Baron Ernest von Bagge. The figure of Baron Bagge is extremely curious. This was a fairly common type of patron in the XNUMXth century, who organized a music salon at his home, famous throughout Paris. With great influence in society and connections, he helped many aspiring musicians to get on their feet. The baron’s salon was a kind of “trial stage”, passing through which the performers got access to the “Concert Spirituel”. However, the outstanding Parisian musicians were attracted to him to a much greater extent by his encyclopedic education. No wonder that a circle gathered in his salon, shining with the names of outstanding musicians of Paris. Another patron of the arts of the same kind was the Parisian banker La Poupliniere. Gavignier was also on close friendly terms with him. “Pupliner took on his own the best musical concerts that were known at that time; the musicians lived with him and prepared together in the morning, surprisingly amicably, those symphonies that were to be performed in the evening. All skillful musicians who came from Italy, violinists, singers and singers were received, placed in his house, where they were fed, and everyone tried to shine at his concerts.

In 1763, Gavignier met Leopold Mozart, who arrived here in Paris, the most famous violinist, the author of the famous school, translated into many European languages. Mozart spoke of him as a great virtuoso. The popularity of Gavignier as a composer can be judged by the number of his works performed. They were often included in programs by Bert (March 29, 1765, March 11, April 4 and September 24, 1766), the blind violinist Flitzer, Alexander Dön, and others. For the XNUMXth century, this kind of popularity is not a frequent phenomenon.

Describing the character of Gavinier, Lorancey writes that he was noble, honest, kind and completely devoid of prudence. The latter was clearly manifested in connection with a rather sensational story in Paris at the end of the 60s regarding the philanthropic undertaking of Bachelier. In 1766, Bachelier decided to establish a school of painting in which the young artists of Paris, who did not have the means, could receive an education. Gavignier took a lively part in the creation of the school. He organized 5 concerts to which he attracted outstanding musicians; Legros, Duran, Besozzi, and in addition, a large orchestra. The proceeds from the concerts went to the school fund. As “Mercury” wrote, “fellow artists united for this act of nobility.” You need to know the manners that prevailed among the musicians of the XVIII century in order to understand how difficult it was for Gavinier to conduct such a collection. After all, Gavignier forced his colleagues to overcome the prejudices of musical caste isolation and come to the aid of their brethren in a completely alien kind of art.

In the early 70s, great events took place in the life of Gavignier: the loss of his father, who died on September 27, 1772, and soon – on March 28, 1773 – and his mother. Just at this time the financial affairs of the “Concert Spirituel” fell into decline and Gavignier, together with Le Duc and Gossec, were appointed directors of the institution. Despite personal grief, Gavinier actively set to work. The new directors secured a favorable lease from the municipality of Paris and strengthened the composition of the orchestra. Gavignier led the first violins, Le Duc the second. On March 25, 1773, the first concert organized by the new leadership of the Concert Spirituel took place.

Having inherited the property of his parents, Gavignier again showed his inherent qualities of a silver-bearer and a man of rare spiritual kindness. His father, a toolmaker, had a large clientele in Paris. There was a fair amount of unpaid bills from his debtors in the papers of the deceased. Gavinier threw them into the fire. According to contemporaries, this was a reckless act, since among the debtors were not only really poor people who found it difficult to pay bills, but also rich aristocrats who simply did not want to pay them.

In early 1777, after the death of Le Duc, Gavignier and Gossec left the directorate of the Concert Spirituel. However, a major financial trouble awaited them: through the fault of the singer Legros, the amount of the lease agreement with the city Bureau of Paris was increased to 6000 livres, attributed to the annual entreprise of the Concert. Gavignier, who perceived this decision as an injustice and an insult inflicted on him personally, paid the orchestra members everything they were entitled to until the end of his directorship, refusing in their favor from his fee for the last 5 concerts. As a result, he retired with almost no means of subsistence. He was saved from poverty by an unexpected annuity of 1500 livres, which was bequeathed to him by a certain Madame de la Tour, an ardent admirer of his talent. However, the annuity was assigned in 1789, and whether he received it when the revolution began is not known. Most likely not, because he served in the orchestra of the Theater of the Rue Louvois for a fee of 800 livres a year – an amount more than a meager for that time. However, Gavignier did not perceive his position as humiliating at all and did not lose heart at all.

Among the musicians of Paris, Gavignier enjoyed great respect and love. At the height of the revolution, his students and friends decided to arrange a concert in honor of the elderly maestro and invited opera artists for this purpose. There was not a single person who would refuse to perform: singers, dancers, up to Gardel and Vestris, offered their services. They made up a grandiose program of the concert, after which the performance of the ballet Telemak was supposed to be performed. The announcement indicated that the famous “Romance” by Gavinier, which is still on everyone’s lips, will be played. The surviving program of the concert is very extensive. It includes “Haydn’s new symphony”, a number of vocal and instrumental numbers. The concert symphony for two violins and orchestra was played by the “Kreutzer brothers” – the famous Rodolphe and his brother Jean-Nicolas, also a talented violinist.

In the third year of the revolution, the Convention allocated a large sum of money for the maintenance of outstanding scientists and artists of the republic. Gavignier, along with Monsigny, Puto, Martini, was among the pensioners of the first rank, who were paid 3000 livres a year.

On 18 Brumaire of the 8nd year of the republic (November 1793, 1784), the National Institute of Music (future conservatory) was inaugurated in Paris. The Institute, as it were, inherited the Royal School of Singing, which existed since 1794. Early in XNUMX Gavignier was offered the position of professor of violin playing. He remained in this position until his death. Gavinier devoted himself to teaching zealously and, despite his advanced age, found the strength to conduct and be among the jury for the distribution of prizes at conservatory competitions.

As a violinist, Gavignier retained the mobility of technique until the last days. A year before his death, he composed “24 matine” – the famous etudes, which are still being studied in conservatories today. Gavignier performed them daily, and yet they are extremely difficult and accessible only to violinists with a very developed technique.

Gavignier died on September 8, 1800. Musical Paris mourned this loss. The funeral cortege was attended by Gossek, Megul, Cherubini, Martini, who came to pay their last tribute to their deceased friend. Gossek gave the eulogy. Thus ended the life of one of the greatest violinists of the XVIII century.

Gavignier was dying surrounded by friends, admirers and students in his more than modest home on the Rue Saint-Thomas, near the Louvre. He lived on the second floor in a two-room apartment. The furnishings in the hallway consisted of an old travel suitcase (empty), a music stand, several straw chairs, a small closet; in the bedroom there was a chimney-dressing table, copper candlesticks, a small fir-wood table, a secretary, a sofa, four armchairs and chairs upholstered in Utrecht velvet, and a literally beggarly bed: an old couch with two backs, covered with a cloth. All property was not worth 75 francs.

On the side of the fireplace, there was also a closet with various objects piled up in a heap – collars, stockings, two medallions with images of Rousseau and Voltaire, Montaigne’s “Experiments”, etc. one, gold, with the image of Henry IV, the other with a portrait of Jean-Jacques Rousseau. In the closet are used items valued at 49 francs. The greatest treasure in all of Gavignier’s legacy is a violin by Amati, 4 violins and a viola by his father.

The biographies of Gavinier indicate that he had a special art of captivating women. It seemed that he “lived by them and lived for them.” And besides, he always remained a true Frenchman in his chivalrous attitude towards women. In the cynical and depraved environment, so characteristic of the French society of the pre-revolutionary decades, in an environment of open courtesy, Gavignier was an exception. He was distinguished by a proud and independent character. High education and a bright mind brought him closer to the enlightened people of the era. He was often seen in the house of Pupliner, Baron Bagge, with Jean-Jacques Rousseau, with whom he was on close friendly terms. Fayol tells a funny fact about this.

Rousseau greatly appreciated the conversations with the musician. One day he said: “Gavinier, I know that you love cutlets; I invite you to taste them.” Arriving at Rousseau, Gavinier found him frying cutlets for the guest with his own hands. Laurency emphasizes that everyone was well aware of how difficult it was for the usually little sociable Rousseau to get along with people.

Gavinier’s extreme vehemence sometimes made him unfair, irritable, caustic, but all this was covered with extraordinary kindness, nobility, and responsiveness. He tried to come to the aid of every person in need and did it disinterestedly. His responsiveness was legendary, and his kindness was felt by everyone around him. He helped some with advice, others with money, and others with the conclusion of lucrative contracts. His disposition – cheerful, open, sociable – remained so until his old age. The old man’s grumbling was not characteristic of him. It gave him real satisfaction to pay tribute to young artists, he had an exceptional breadth of views, the finest sense of time and the new that it brought to his beloved art.

He is every morning. devoted to pedagogy; worked with students with amazing patience, perseverance, zeal. The students adored him and did not miss a single lesson. He supported them in every possible way, instilled faith in himself, in success, in the artistic future. When he saw a capable musician, he took him as a student, no matter how difficult it was for him. Having once heard the young Alexander Bush, he said to his father: “This child is a real miracle, and he will become one of the first artists of his time. Give it to me. I want to direct his studies to help develop his early genius, and my duty will be truly easy, because the sacred fire burns in him.

His complete indifference to money also affected his students: “He never agreed to take a fee from those who dedicate themselves to music. Moreover, he always gave preference to poor students over rich ones, whom he sometimes made to wait for hours until he himself finished classes with some young artist deprived of funds.

He constantly thought about the student and his future, and if he saw that someone was incapable of playing the violin, he tried to transfer him to another instrument. Many were literally kept at their own expense and regularly, every month, supplied with money. No wonder that such a teacher became the founder of an entire school of violinists. We will name only the most brilliant, whose names were widely known in the XVIII century. These are Capron, Lemierre, Mauriat, Bertom, Pasible, Le Duc (senior), Abbé Robineau, Guerin, Baudron, Imbo.

Gavinier the artist was admired by the outstanding musicians of France. When he was only 24 years old, L. Daken did not write dithyrambic lines about him: “What sounds do you hear! What a bow! What strength, grace! This is Baptiste himself. He captured my whole being, I’m delighted! He speaks to the heart; everything sparkles under his fingers. He performs Italian and French music with equal perfection and confidence. What brilliant cadences! And his fantasy, touching and tender? How long have laurel wreaths, besides the most beautiful ones, been intertwined to adorn such a young brow? Nothing is impossible for him, he can imitate everything (i.e. comprehend all styles – L.R.). He can only surpass himself. All Paris comes running to listen to him and cannot hear enough, he is so delightful. About him, one can only say that talent does not wait for the shadows of the years … “

And here is another review, no less dithyrambic: “Gavinier from birth has all the qualities that a violinist could wish for: impeccable taste, left hand and bow technique; he reads excellently from a sheet, with incredible ease comprehends all genres, and, moreover, it costs him nothing to master the most difficult techniques, the development of which others have to spend a long time studying. His playing embraces all styles, touches with the beauty of tone, strikes with performance.

About the extraordinary ability of Gavinier to impromptu perform the most difficult works are mentioned in all biographies. One day, an Italian, having arrived in Paris, decided to compromise the violinist. In his undertaking, he involved his own uncle, the Marquis N. In front of a large company that gathered at the evening at the Parisian financier Pupliner, who maintained a magnificent orchestra, the Marquis suggested that Gavignier play a concert specially commissioned for this purpose by some composer, incredibly difficult, and besides, on purpose badly rewritten. Looking at the notes, Gavignier asked to reschedule the performance for the next day. Then the marquis ironically remarked that he assessed the violinist’s request “as a retreat of those who claim to be able to perform at a glance any music they offer.” Hurt Gavignier, without saying a word, took the violin and played the concerto without hesitation, without missing a single note. The Marquis had to admit that the performance was excellent. However, Gavignier did not calm down and, turning to the musicians who accompanied him, said: “Gentlemen, Monsieur Marquis showered me with thanks for the way I performed the concerto for him, but I am extremely interested in the opinion of Monsieur Marquis when I play this work for myself. Start over!” And he played the concerto in such a way that this, on the whole, mediocre work appeared in a completely new, transfigured light. There was a thunder of applause, which meant the complete triumph of the artist.

The performance qualities of Gavinier emphasize the beauty, expressiveness and power of sound. One critic wrote that the four violinists of Paris, who had the strongest tone, playing in unison, could not surpass Gavignier in sounding power and that he freely dominated an orchestra of 50 musicians. But he conquered his contemporaries even more with the penetrating, expressiveness of the game, forcing “as if to speak and sigh his violin.” Gavignier was especially famous for his performance of adagios, slow and melancholic pieces, belonging, as they said then, to the sphere of “music of the heart”.

But, half a salute, the most unusual feature of Gavignier’s performing appearance must be recognized as his subtlest sense of different styles. He was ahead of his time in this regard and seemed to look into the middle of the XNUMXth century, when the “art of artistic impersonation” became the main advantage of the performers.

Gavignier, however, remained a true son of the eighteenth century; his striving to perform compositions from different times and peoples undoubtedly has an educational basis. Faithful to the ideas of Rousseau, sharing the philosophy of the Encyclopedists, Gavignier tried to transfer its principles into his own performance, and natural talent contributed to the brilliant realization of these aspirations.

Such was Gavignier – a true Frenchman, charming, elegant, intelligent and witty, possessing a fair amount of crafty skepticism, irony, and at the same time cordial, kind, modest, simple. Such was the great Gavignier, whom musical Paris admired and was proud of for half a century.

L. Raaben