Oleg Moiseevich Kagan (Oleg Kagan) |

Oleg Kagan

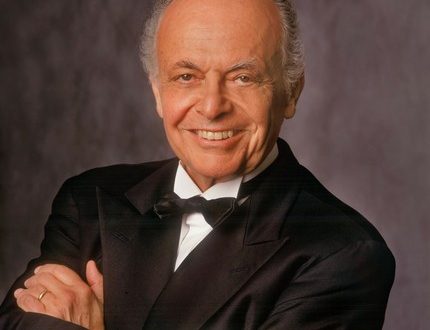

Oleg Moiseevich Kagan (November 22, 1946, Yuzhno-Sakhalinsk – July 15, 1990, Munich) – Soviet violinist, Honored Artist of the RSFSR (1986).

After the family moved to Riga in 1953, he studied violin at the music school at the conservatory under Joachim Braun. At the age of 13, the famous violinist Boris Kuznetsov moved Kagan to Moscow, taking him to his class at the Central Music School, and since 1964 – at the conservatory. In the same 1964, Kagan won fourth place at the Enescu Competition in Bucharest, a year later he won the Sibelius International Violin Competition, a year later he won the second prize at the Tchaikovsky Competition, and finally, in 1968, he won a convincing victory at the Bach Competition in Leipzig.

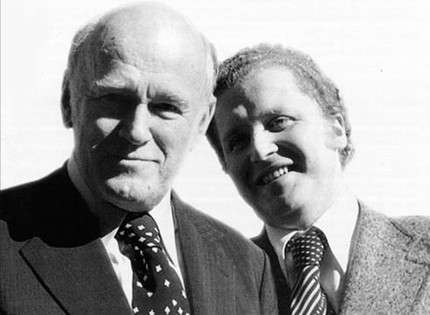

After Kuznetsov’s death, Kagan moved to the class of David Oistrakh, who helped him record a cycle of five Mozart violin concertos. Since 1969, Kagan began a long-term creative collaboration with Svyatoslav Richter. Their duet soon became world-famous, and Kagan became close friends with the greatest musicians of that time – cellist Natalia Gutman (later to become his wife), violist Yuri Bashmet, pianists Vasily Lobanov, Alexei Lyubimov, Eliso Virsaladze. Together with them, Kagan played in chamber ensembles at a festival in the city of Kuhmo (Finland) and at his own summer festival in Zvenigorod. In the late 1980s, Kagan planned to organize a festival in Kreut (Bavarian Alps), but a premature death from cancer prevented him from realizing these plans. Today, the festival in Kreuth is held in memory of the violinist.

Kagan earned a reputation as a brilliant chamber performer, although he also performed major concert works. For example, he and his wife Natalia Gutman performed the Brahms Concerto for violin and cello with the orchestra, for example, became very famous. Alfred Schnittke, Tigran Mansuryan, Anatole Vieru dedicated their compositions to the duet of Kagan and Gutman.

Kagan’s repertoire included works by contemporary authors who were rarely performed at that time in the USSR: Hindemith, Messiaen, composers of the New Vienna School. He became the first performer of works dedicated to him by Alfred Schnittke, Tigran Mansuryan, Sofia Gubaidulina. Kagan was also a brilliant interpreter of the music of Bach and Mozart. Numerous recordings of the musician have been released on CD.

In 1997, director Andrey Khrzhanovsky made the film Oleg Kagan. Life after life.”

He was buried in Moscow at the Vagankovsky cemetery.

The history of the performing arts of the past century knows many outstanding musicians whose careers were cut short at the peak of their artistic powers – Ginette Neve, Miron Polyakin, Jacqueline du Pré, Rosa Tamarkina, Yulian Sitkovetsky, Dino Chiani.

But the epoch passes away, and documents remain from it, among which we find, among other things, the recordings of young musicians who died, and the astringent matter of time firmly connects their play in our minds with the time that gave birth to and absorbed them.

Objectively speaking, the era of Kagan left with him. He died two days after his last concert as part of the festival he had just organized in Bavarian Kreuth, at the very top of the summer of 1990, in the cancer ward of the Munich hospital – and in the meantime, a rapidly progressing tumor was corroding the culture and the very country in which he was born , crossed in his youth from end to end (born in Yuzhno-Sakhalinsk, began to study in Riga …), and which survived him for a very short time.

It would seem that everything is clear and natural, but the case of Oleg Kagan is quite special. He was one of those artists who seemed to stand above their time, above their era, at the same time belonging to them and looking, at the same time, into the past and into the future. Kagan managed to combine in his art something, at first glance, incompatible: the perfectionism of the old school, coming from his teacher, David Oistrakh, the rigor and objectivity of interpretation, which was required by the trends of his time, and at the same time – a passionate impulse of the soul, eager for freedom from the gorges of musical text (bringing him closer to Richter).

And his constant appeal to the music of his contemporaries – Gubaidulina, Schnittke, Mansuryan, Vier, the classics of the twentieth century – Berg, Webern, Schoenberg, betrayed in him not just an inquisitive researcher of new sound matter, but a clear realization that without updating expressive means, music – and along with it, the art of the performer will turn into an expensive toy simply into a museum value (what would he think if he looked at today’s philharmonic posters, which narrowed the style almost to the level of the most deaf Soviet era! ..)

Now, after many years, we can say that Kagan seemed to have passed the crisis that Soviet performance experienced at the end of the existence of the USSR – when the sheer boredom of interpretations was passed off as seriousness and sublimity, when in search of overcoming this boredom the instruments were torn to pieces, wishing to show the depth of the psychological concept, and even seeing in it an element of political opposition.

Kagan did not need all these “supports” – he was such an independent, deeply thinking musician, his performing possibilities were so boundless. He argued, so to speak, with outstanding authorities – Oistrakh, Richter – at their own level, convincing them that he was right, as a result of which outstanding performing masterpieces were born. Of course, one can say that Oistrakh instilled in him an exceptional inner discipline that allowed him to move in his art along an ascending even line, the fundamental approach to the musical text – and in this he, of course, is the continuer of his tradition. However, in Kagan’s interpretation of the same compositions – sonatas and concertos by Mozart, Beethoven, for example – one finds that very transcendent height of flight of thought and feeling, the semantic loading of each sound, which Oistrakh could not afford, being a musician of another time with others inherent in him values.

It is interesting that Oistrakh suddenly discovers this careful refinement in himself, becoming Kagan’s accompanist on the published recordings of Mozart’s concertos. With the change of role, he, as it were, continues his own line in the ensemble with his brilliant student.

It is possible that it was from Svyatoslav Richter, who early noticed the brilliant young violinist, that Kagan adopted this supreme enjoyment of the value of each articulated tone, transmitted to the public. But, unlike Richter, Kagan was extremely strict in his interpretations, did not let his emotions overwhelm him, and in the famous recordings of Beethoven’s and Mozart’s sonatas it seems sometimes – especially in slow movements – how Richter yields to the strict will of the young musician, evenly and confidently making his way from one peak of the spirit to another. Needless to say, what an influence he had on his peers who worked with him – Natalia Gutman, Yuri Bashmet – and on his students, alas, not numerous due to the time allotted to him by fate!

Maybe Kagan was destined to become just one of those musicians who are not shaped by the era, but who create it themselves. Unfortunately, this is only a hypothesis, which will never be confirmed. The more valuable for us is every piece of tape or videotape that captures the art of an amazing musician.

But this value is not of a nostalgic order. Rather – while it is still possible, while the 70s – 80s. of the last century did not finally become history – these documents can be considered as a guideline leading to the revival of the high spirit of Russian performance, the brightest spokesman of which was Oleg Moiseevich Kagan.

Company “Melody”