Note durations in music: how are they written and how are they counted?

Contents

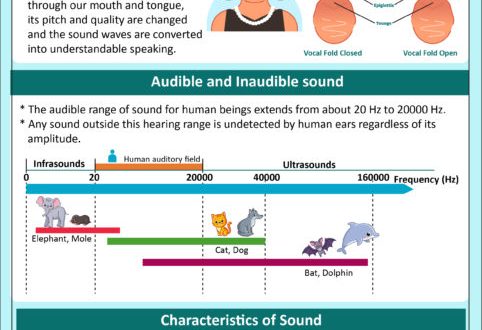

Any musical sound can be not only high or low, but also long or short. And this property of sound is called duration. The duration of the notes is the topic of our conversation today.

You probably noticed that the notes are not only written on different rulers of the stave, but also look different? For some reason, some are painted over and with tails, others are without tails, and others are completely empty inside. These are different durations.

Basic note values

First, we will suggest that you simply consider all the durations that are often found in music and memorize their names, and a little later we will deal with their meaning in musical rhythm and how to feel them.

There are not so many main durations. It:

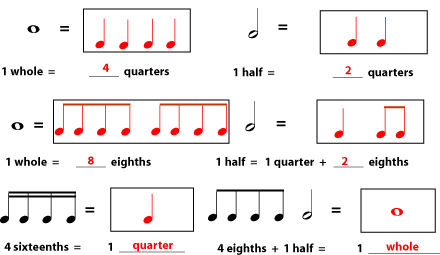

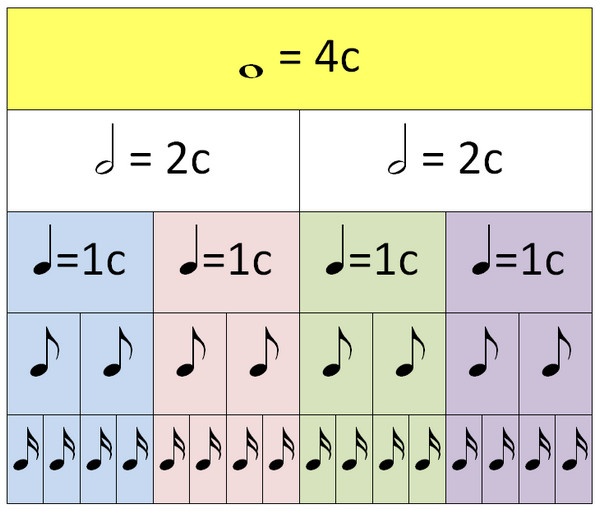

WHOLE – is considered the longest duration, it is an ordinary circle or, if you like, an oval, an ellipse, empty inside – not filled in. In musical circles, they like to call whole notes “potatoes”.

HALF is a duration that is exactly two times shorter than an integer. For example, if you hold a whole note for 4 seconds, then a half note is only 2 seconds (all these seconds are now purely conventional units, so that you just understand the principle). A half duration looks almost the same as a whole one, only the head (potato) is not so fat, and it also has a stick (correctly speaking – calm).

FOURTH is a duration that is half the length of a half note. And if you compare it with a whole note, then it will be four times shorter (after all, a quarter is 1/4 of the whole). So, if a whole sounds 4 seconds, a half – 2 seconds, then a quarter will be played for only 1 second. A quarter note is necessarily painted over and it also has a calm, like a half note.

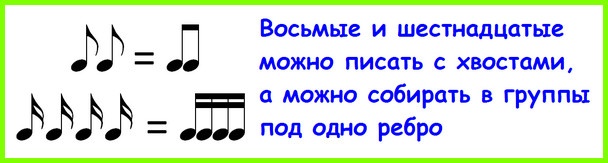

EIGHT – as you probably guessed, an eighth note is twice as short as a quarter note, four times as short as a half note, and it takes eight pieces of eighth notes to fill the time of one whole note (because an eighth note is 1/ 8 part of the whole). And it will last, respectively, only half a second (0,5 s). The eighth note, or as musicians like to say, the eighth note, is the tailed note. It differs from the quarter in the presence of a tail (mane). In general, scientifically, this tail is called a flag. Eighths often like to gather in groups of two or four, then all the tails are connected and form one common “roof” (correctly speaking – an edge).

THE SIXTEENTH – twice as short as an eight, four times as short as a quarter, and to fill a whole note, you need 16 pieces of such notes. And for one second, according to our conditional scheme, there are as many as four sixteenth notes. In its writing, in appearance, this duration is very similar to an eighth, only it has two tails (two pigtails). The sixteenths like to gather in companies of four (sometimes two, of course), and they are connected by as many as two ribs (two “roofs”, two crossbars).

Of course, there are also durations smaller than sixteenths – for example, 32nd or 64th, but for now it’s not worth bothering with them. Now the most important thing is to understand the basic principles, then the rest will come by itself. By the way, there are durations that are longer than a whole (for example, a brevis), but this is also a topic for a separate discussion.

The ratio of durations to each other

The following picture will show a table of splitting durations. Each new, smaller duration arises when a larger one is divided into two parts. This principle is called the “even division principle”. A whole note is divided by the number two in different degrees, that is, into 2, 4, 8, 16, 32 or another, greater number of parts. From here, by the way, come the names “quarter”, “eighth”, “sixteenth” and others. Look at this table and try to understand it.

Perhaps the most important thing in studying durations is understanding their relationship to each other. The fact is that musical time is conditional, it is not measured by precisely adjusted seconds. And therefore, we cannot say exactly how long a whole or half note will last in seconds. The examples that we gave are conditional – just one of the possible options. What then to do? How then exactly to keep the rhythm?

What is musical time?

It turns out that music has its own unit of time. It’s a pulse beat. Yes, in music, like in any living organism, there is a pulse. The pulse beats are uniform, but they can be different in speed. The pulse can beat quickly, speedily, or maybe slowly, calmly. Thus, it turns out that the pulse beat as a unit of time is not constant, changeable. It depends on the tempo of the piece. But at the same time this dimension is very important. Why?

Let us assume that the pulse in the piece beats in quarters (that is, quarter notes). Then, knowing the ratio of durations among themselves, you can calculate and feel how other notes will sound. For example, half will take two beats of the pulse in duration, a whole will take four beats of the pulse, and for one beat of the pulse it is necessary to have time to pronounce two eighths or four sixteenth notes.

Rhythmic exercises for different durations

Now let’s try to learn all the same, only in practice.

EXERCISE #1. Let’s say that our pulse beats in even quarters on the note SALT. Everything that we describe here will be presented on a musical example, under which an audio recording is also placed. Hear how it sounds. Catch that even rhythm. Clap your hands, snap your fingers or beat the pen on the table, and after the melody ends, try to continue the same rhythm or repeat yourself without audio.

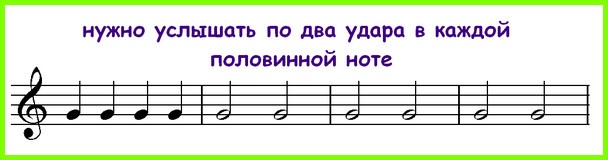

EXERCISE #2. Now try to catch the sound of other durations. For example, half. The half sounds, of course, are twice as slow as the quarters with which our pulse beats in this case. At the beginning of the next example, you will hear beats of the pulse in quarters – we will remind you of this temperature in this way. Quarter notes will sound four times, and then half durations will go. In each half, try to catch, feel the continuation of the same blows. That is, the second blow in a half note you need to imagine, as it were, to feel inside yourself.

Happened? If yes, then good. If not, then try another version of the exercise. Now on the musical example you will see two voices. The lower voice will play softly in even fourths on the note G in the bass clef, and the upper voice will switch to half notes after the first four beats, which will play louder on the SI note. Thus, in each half you will be able to hear the real echo of the second beat of the pulse, which will play along with the second voice. After this variation of the exercise, you can return to the first variation.

EXERCISE #3. Now you will need to catch the rhythm of the eighth notes. Eighth notes are played faster than quarter notes, and therefore there will be two eighth notes for each beat of the pulse. In the example below, four quarter beats will go first, as always, and then eighth beats will go. At the same time, you knock your pulse to yourself in even quarters. Feel like there are two eighth notes per beat.

And the second version of this exercise. With two voices, in the second voice, from the beginning to the end, the pulsation is preserved in even quarters on the note SALT. In the upper voice there is a switch to eighth notes.

EXERCISE #4. This task will introduce you to the rhythm of sixteenth notes. There are four of them for one beat of the pulse. We will be accelerating gradually. First there will be 4 beats with quarters, then 8 beats with eights, and only then will sixteenths go. The sixteenths here, for convenience, are collected in groups of four pieces under one “roof” (under one rib). The beginning of each group coincides with the beat of the main pulse.

And the second version of the same exercise: one voice – in the treble clef, the other – in the bass. You should be able to do everything.

How to count note durations?

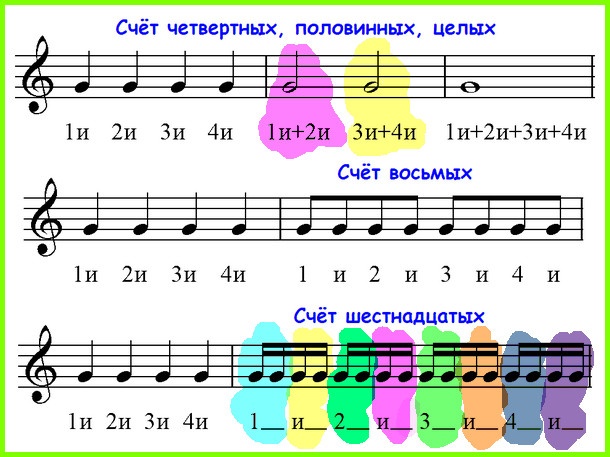

When beginning musicians learn pieces for their instrument, they often have to count out loud. Pulse beats are counted. The account can be kept up to two, up to three or up to four. Moreover, in order to make it easier to divide the beat of the pulse in half when playing with eighth durations, a separating syllable “and” is inserted after each count. So it turns out that the musical account looks like this: ONE-I, TWO-I, THREE-I, FOUR-I or ONE-I, TWO-I, THREE-I, and sometimes just ONE-I, TWO-I.

How to figure it out. Everything is pretty simple here. A whole note is counted up to four, since four beats of the pulse are placed in it (ONE-AND, TWO-AND, THREE-AND, FOUR-AND). Half is two beats, so it counts up to two (ONE-AND, TWO-AND or THREE-AND, FOUR-AND, if the half falls on the third and fourth beats of the pulse). Quarters are counted one piece for each count: one quarter for ONE-I, the second quarter for TWO-I, the third for THREE-I, and the fourth for FOUR-I.

This additive “I” exists for convenient counting of eights. Single octuplets are rare, more often they come across in pairs or four pieces. And then one eighth is counted on the count number itself (on ONE, TWO, THREE or FOUR), and the second eight is always on “I”.

Calm spelling

We remind you that STIHL is a stick at the note. These sticks are attached to the head and directed both up and down. The direction of the stems depends on the position of the note on the stave. The rule is very simple: up to the third line, the sticks look up, and starting from the third and above, down.

That’s all for today, but the theme of rhythm is fraught with many more interesting discoveries. We will definitely draw your attention to them in future releases. Now review the material again, think about what questions you want to ask. Anything you think of, write in the comments.

And finally – a portion of good music for you. Let it be the famous Prelude in G minor by Sergei Rachmaninoff performed by pianist Valentina Lisitsa.