Melody |

other Greek μελῳδία – chant of lyric poetry, from μέλος – chant, and ᾠδή – singing, chant

Unanimously expressed musical thought (according to IV Sposobin). In homophonic music, the function of melody is usually inherent in the upper, leading voice, while the secondary middle voices are harmonic. fill and bass constituting the harmonic. support, do not fully possess typical. melody qualities. M. represents the main. the beginning of the music; “the most essential aspect of music is melody” (S. S. Prokofiev). The task of other components of music—counterpoint, instrumentation, and harmony—is to “complement, complete the melodic thought” (M. I. Glinka). Melody can exist and render art. influence in monophony, in combination with melodies in other voices (polyphony) or with homophonic, harmonic. accompaniment (homophony). Single voice is Nar. music pl. peoples; among a number of peoples, monophony was unity. kind of prof. music in certain historical periods or even throughout their history. In the melody, in addition to the intonational principle, which is most important in music, such muses also appear. elements like mode, rhythm, music. structure (form). It is through the melody, in the melody, that they first of all reveal their own expressions. and organizing opportunities. But even in polyphonic music M. completely dominates, she is the “soul of a musical work” (D. D. Shostakovich).

The article discusses the etymology, meaning and history of the term “M.” (I), the nature of M. (II), its structure (III), history (IV), teachings about M. (V).

I. Greek. the word melos (see Melos), which forms the basis of the term “M.”, originally had a more general meaning and denoted a part of the body, as well as the body as an articulated organic. whole (G. Hyushen). In this sense, the term “M.” y Homer and Hesiod is used to denote the succession of sounds that form such a whole, therefore, the original. the meaning of the term melodia can also be understood as “a way of singing” (G. Huschen, M. Vasmer). From the root mel – in Greek. a large number of words occur in the language: melpo – I sing, I lead round dances; melograpia – songwriting; melopoipa – composition of works (lyrical, musical), composition theory; from melpo – the name of the muse Melpomene (“Singing”). Main the term of the Greeks is “melos” (Plato, Aristotle, Aristoxenus, Aristides Quintilian, etc.). Muses. Medieval and Renaissance writers used lat. terms: M., melos, melum (melum) (“melum is the same as canthus” – J. Tinktoris). Modern terminology (M., melodic, melismatic and similar terms of the same root) was entrenched in the musical-theoretical. treatises and in everyday life in the era of the transition from lat. language to national (16-17 centuries), although differences in the interpretation of the relevant concepts persisted until the 20th century. In Russian language, the primordial term “song” (also “melody”, “voice”) with its wide range of meanings gradually (mainly from the end of the 18th century) gave way to the term “M.”. In the 10s. 20th century BV Asafiev returned to the Greek. the term “melos” to define the element melodic. movement, melodiousness (“transfusion of sound into sound”). Using the term “M.”, for the most part, they emphasize one of its sides and spheres of manifestation outlined above, to a certain extent abstracting from the rest. In this connection, the main term meanings:

1) M. – a sequential series of sounds interconnected into a single whole (M. line), as opposed to harmony (more precisely, a chord) as a combination of sounds in simultaneity (“combinations of musical sounds, … in which sounds follow one after another, … is called a melody” – P. I. Tchaikovsky).

2) M. (in a homophonic letter) – the main voice (for example, in the expressions “M. and accompaniment”, “M. and bass”); at the same time, M. does not mean any horizontal association of sounds (it is also found in the bass and in other voices), but only such, which is the focus of melodiousness, music. connectedness and meaning.

3) M. – semantic and figurative unity, “music. thought”, concentration of music. expressiveness; as an indivisible whole unfolded in time, M.-thought presupposes a procedural flow from the starting point to the final one, which are understood as the temporal coordinates of a single and self-contained image; successively appearing parts of M. are perceived as belonging to the same only gradually looming essence. The integrity and expressiveness of M. also appear to be aesthetic. a value similar to the value of music (“… But love is also a melody” – A. S. Pushkin). Hence the interpretation of melody as a virtue of music (M. – “the succession of sounds that … produce a pleasant or, if I may say so, harmonious impression”, if this is not the case, “we call the succession of sounds non-melodious” – G. Bellerman).

II. Having emerged as a primary form of music, M. retains traces of its original connection with speech, verse, body movement. The similarity with speech is reflected in a number of features of the structure of M. like music. whole and in its social functions. Like speech, M. is an appeal to the listener with the aim of influencing him, a way of communicating people; M. operates with sound material (vocal M. – the same material – voice); expression M. relies on a certain emotional tone. Pitch (tessitura, register), rhythm, loudness, tempo, shades of timbre, a certain dissection, and logic are important both in speech and in speech. the ratio of parts, especially the dynamics of their changes, their interaction. The connection with the word, speech (in particular, oratorical) also appears in the average value of melodic. a phrase corresponding to the duration of a human breath; in similar (or even general) methods of embellishing speech and melody (muz.-rhetoric. figures). The structure of music. thinking (manifested in M.) reveals the identity of its most general laws with the corresponding general logic. principles of thought (cf. rules for constructing speech in rhetoric – Inventio, Dispositio, Elaboratio, Pronuntiatio – with the general principles of music. thinking). A deep comprehension of the commonality of the real-life and conditional-artistic (musical) contents of sound speech allowed B. AT. Asafiev to characterize the sound expression of muses with the term intonation. thought, understood as a phenomenon socially determined by the public muses. consciousness (according to him, “the intonation system becomes one of the functions of social consciousness”, “music reflects reality through intonation”). Melody difference. intonation from speech lies in a different nature of the melodic (as well as musical in general) – in operating with stepped tones of exactly fixed height, muses. intervals of the corresponding tuning system; in modal and special rhythmic. organization, in a certain specific musical structure of M. Similarity to verse is a particular and special case of connection with speech. Standing out from the ancient syncretic. “Sangita”, “trochai” (the unity of music, words and dance), M., music has not lost that common thing that connected it with verse and body movement – metrorhythm. organization of time (in vocal, as well as in marching and dancing). applied music, this synthesis is partly or even completely preserved). “Order in motion” (Plato) is the common thread that naturally holds all these three areas together. The melody is very diverse and can be classified according to dec. signs – historical, stylistic, genre, structural. In the most general sense, one should fundamentally separate M. monophonic music from M. polyphonic. In monotone M. covers all music. the whole, in polyphony, is only one element of the fabric (even if it is the most important). Therefore, with regard to monophony, a complete coverage of the doctrine of M. is an exposition of the whole theory of music. In polyphony, the study of a separate voice, even if it is the main one, is not entirely legitimate (or even illegal). Or it is a projection of the laws of the full (polyphonic) text of the muses. works for the main voice (then this is not a “doctrine of melody” in the proper sense). Or it separates the main voice from others that are organically connected with it. voices and fabric elements of living music. organism (then the “doctrine of melody” is defective in music. relation). The connection of the main voice with other voices of homophonic music. tissue should not, however, be absolutized. Almost any melody of a homophonic warehouse can be framed and indeed is framed in polyphony in different ways. Nevertheless, between the isolated M. and, with dr. side, a separate consideration of harmony (in the “teachings of harmony”), counterpoint, instrumentation, there is no sufficient analogy, because the latter study, albeit one-sidedly, more fully the whole of music. Musical thought (M.) of a polyphonic composition in one M. never fully expressed; this is achieved only in the aggregate of all votes. Therefore, complaints about the underdevelopment of the science of M., about the lack of an appropriate training course (E. Tokh and others) are illegal. The spontaneously established relationship between the main ice disciplines is quite natural, at least in relation to Europe. classical music, polyphonic in nature. Hence specific. problems of the doctrine of M. as a scientific disciplines – questions relating to the actual melodic.

III. M. is a multicomponent element of music. The dominant position of music among other elements of music is explained by the fact that music combines a number of the components of music listed above, in connection with which music can and often does represent all of the music. whole. Most specific. component M. – pitch line. Others are themselves. elements of music: modal-harmonic phenomena (see Harmony, Mode, Tonality, Interval); meter, rhythm; structural division of the melody into motifs, phrases; thematic relations in M. (see Musical form, Theme, Motive); genre features, dynamic. nuances, tempo, agogics, performing shades, strokes, timbre coloring and timbre dynamics, features of textural presentation. The sound of a complex of other voices (especially in a homophonic warehouse) has a significant impact on M., giving its expression a special fullness, generating subtle modal, harmonic, and intonation nuances, creating a background that favorably sets off M.. The action of this whole complex of elements closely related to each other is carried out through M. and is perceived as if all this belonged only to M.

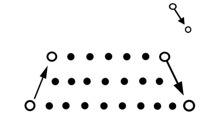

Patterns of melodic. lines are rooted in elementary dynamic. properties of register ups and downs. The prototype of any M. – vocal M. reveals them with the greatest distinctness; instrumental M. is felt on the model of vocal. The transition to a higher frequency of vibrations is a consequence of some effort, manifestation of energy (which is expressed in the degree of voice tension, string tension, etc.), and vice versa. Therefore, any movement of the line upwards is naturally associated with a general (dynamic, emotional) rise, and downwards with a decline (sometimes composers deliberately violate this pattern, combining the rise of the movement with a weakening of the dynamics, and the descent with an increase, and thereby achieve a peculiar expressive effect). The described regularity is manifested in a complex interweaving with the regularities of modal gravity; Thus, a higher sound of a fret is not always more intense, and vice versa. Bends melodic. lines, rises and falls are sensitive to display shades vnutr. emotional state in their elemental form. The unity and certainty of music are determined by the attraction of the sound stream to a firmly fixed reference point—the abutment (“melodic tonic,” according to B. V. Asafiev), around which a gravitational field of adjacent sounds is formed. Based on the acoustically perceived by the ear. kinship, a second support arises (most often a quart or a fifth above the final foundation). Thanks to the fourth-quint coordination, the mobile tones that fill the space between the foundations eventually line up in the diatonic order. gamma. The shift of the sound M. for a second up or down ideally “erases the trace” of the previous one and gives a feeling of the shift, movement that has occurred. Therefore, the passage of seconds (Sekundgang, the term of P. Hindemith) is specific. means of M. (the passage of seconds forms a kind of “melodic trunk”), and the elementary linear fundamental principle of M. is, at the same time, its melodic-modal cell. The natural relationship between the energy of the line and the direction of melodic. movement determines the oldest model of M. – a descending line (“primary line”, according to G. Schenker; “the leading reference line, most often descending in seconds”, according to I. V. Sposobin), which begins with a high sound (“head tone” of the primary line, according to G. Schenker; “top-source”, according to L. A. Mazel) and ends with a fall to the lower abutment:

Russian folk song “There was a birch in the field.”

The principle of the descent of the primary line (the structural framework of M.), which underlies most melodies, reflects the action of linear processes specific to M.: the manifestation of energy in the movements of melodic. line and its category at the end, expressed in the conclusion. recession; the removal (elimination) of tension that occurs at the same time gives a feeling of satisfaction, the extinction of melodic. energy contributes to the cessation of melodic. movement, the end of M. The principle of descent also describes the specific, “linear functions” of M. (L. A. Mazel’s term). “Sounding movement” (G. Grabner) as the essence of melodic. line has as its goal the final tone (final). The initial focus of the melodic. energy forms a “dominance zone” of the dominant tone (the second pillar of the line, in the broad sense – melodic dominant; see the sound e2 in the example above; melodic dominant is not necessarily a fifth higher than the finalis, it can be separated from it by a fourth, a third ). But rectilinear movement is primitive, flat, aesthetically unattractive. Arts. the interest is in its various colorings, complications, detours, moments of contradiction. The tones of the structural core (the main descending line) are overgrown with branching passages, masking the elementary nature of the melodic. trunk (hidden polyphony):

A. Thomas. “Fly to us, quiet evening.”

Initial melody. the dominant as1 is decorated with an auxiliary. sound (indicated by the letter “v”); each structural tone (except the last one) gives life to the melodic sounds that grow out of it. “escape”; the ending of the line and the structural core (sounds es-des) has been moved to another octave. As a result, melodic the line becomes rich, flexible, without losing at the same time the integrity and unity provided by the initial movement of seconds within the consonance as1-des-1 (des2).

In harmonic. European system. In music, the role of stable tones is played by the sounds of a consonant triad (and not quarts or fifths; the triad base is often found in folk music, especially of later times; in the example of the melody of a Russian folk song given above, the contours of a minor triad are guessed). As a result, melodic sounds are unified. dominants – they become the third and fifth of the triad, built on the final tone (prime). And the relationship between melodic sounds. lines (both the structural core and its branches), imbued with the action of triadic connections, are internally rethought. The art is getting stronger. the meaning of hidden polyphony; M. organically merges with other voices; drawing M. can imitate the movement of other voices. Decoration of the head tone of the primary line can grow to the formation of independent. parts; the downward movement in this case covers only the second half of the M. or even moves further away, towards the end. If an ascent is made to the head tone, then the principle of descent is:

turns into a principle of symmetry:

(although the downward movement of the line at the end retains its value of the discharge of melodic energy):

V.A. Mozart. “Little Night Music”, part I.

F. Chopin. Nocturne op. 15 no 2.

Decoration of the structural core can be achieved not only with the help of scale-like side lines (both descending and ascending), but also with the help of moves along the sounds of chords, all forms of melodic. ornaments (figures such as trills, gruppetto; supporting auxiliary ones, similar to mordents, etc.) and any combination of all of them with each other. Thus, the structure of the melody is revealed as a multi-layered whole, where under the upper pattern there is a melodic. figurations are more simple and strict melodic. moves, which, in turn, turn out to be a figuration of an even more elementary construction formed from the primary structural framework. The lowest layer is the simplest base. fret model. (The idea of multiple levels of melodic structure was developed by G. Schenker; his method of sequentially “removing” the layers of the structure and reducing it to primary models was called the “reduction method”; I. P. Shishov’s “method of highlighting the skeleton” is partly related to it.)

IV. The stages of development of melodics coincide with the main. stages in the history of music as a whole. The true source and inexhaustible treasury of M. – Nar. music creation. Nar. M. are an expression of the depths of the collective bunks. consciousness, a naturally occurring “natural” culture, which nourishes the professional, composer’s music. An important part of the Russian nar. creativity are polished over the centuries by ancient peasant M., embodying pristine purity, epic. clarity and objectivity worldview. The majestic calmness, depth and immediacy of feeling are organically connected in them with the severity, “ardor” of the diatonic. fret system. The primary structural frame of the M. of the Russian folk song “There is more than one path in the field” (see example) is the c2-h1-a1 scale model.

Russian folk song “Not one path in the field.”

The organic structure of M. is embodied in a hierarchical. subordination of all these structural levels and is manifested in the ease and naturalness of the most valuable, the upper layer.

Rus. mountains the melody is guided by the triad harmonic. skeleton (typical, in particular, open moves along the sounds of a chord), squareness, for the most part has a clear motive articulation, rhyming melodic cadences:

Russian folk song “Evening ringing”.

Mugham “Shur”. Record no. A. Karaeva.

The most ancient oriental (and partly European) melody is structurally based on the principle of maqam (the principle of raga, fret-model). The repeatedly repeating structural framework-scale (b. h. descending) becomes a prototype (model) for a set of specific sound sequences with specific. variation-variant development of the main series of sounds.

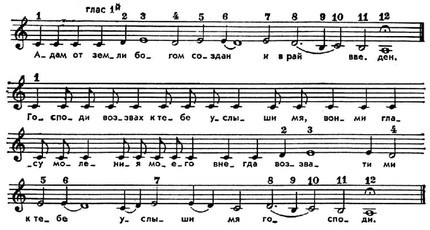

The guiding melody-model is both M. and a certain mode. In India, such a mode-model is called para, in the countries of the Arab-Persian culture and in a number of Central Asian owls. republics – maqam (poppy, mugham, torment), in ancient Greece – nom (“law”), in Java – pathet (patet). A similar role in Old Russian. the music is performed by the voice as a set of chants, on which the M. of this group are sung (the chants are similar to the melody-model).

In ancient Russian In cult singing, the function of the mode model is carried out with the help of the so-called glamors, which are short melodies that have crystallized in the practice of the oral singing tradition and are composed of motifs-chants included in the complex characterizing the corresponding voice.

Poglasica and psalm.

The melodics of antiquity is based on the richest mode-intonational culture, which, by its interval differentiation, surpasses the melodics of later Europe. music. In addition to the two dimensions of the pitch system that still exist today – mode and tonality, in antiquity there was another one, expressed by the concept of gender (genos). Three genders (diatonic, chromatic and enharmonic) with their varieties provided many opportunities for mobile tones (Greek kinoumenoi) to fill the spaces between the stable (estotes) edge tones of the tetrachord (forming a “symphony” of a pure fourth), including (along with diatonic. sounds) and sounds in microintervals – 1/3,3/8, 1/4 tones, etc. Example M. (excerpt) enharmonic. genus (crossed out denotes a decrease of 1/4 tone):

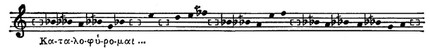

The first stasim from Euripides’ Orestes (fragment).

The M. line has (as in the ancient Eastern M.) a clearly expressed downward direction (according to Aristotle, the beginning of M. in high and ending in low registers contributes to its certainty, perfection). M.’s dependence on the word (Greek music is predominantly vocal), body movements (in dance, procession, gymnastic game) manifested itself in antiquity with the greatest completeness and immediacy. Hence the dominant role of rhythm in music as a factor regulating the order of temporal relations (according to Aristides Quintilian, rhythm is the masculine principle, and melody is feminine). The source is antique. M. is even deeper – this is the area of uXNUMXbuXNUMXb”musculo-motor movements that underlie both music and poetry, i.e. the whole triune chorea ”(R. I. Gruber).

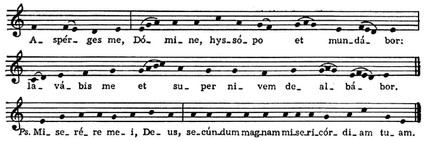

The melody of Gregorian chant (see Gregorian chant) answers to its own Christian liturgical. appointment. The content of the Gregorian M. is completely opposite to the claim of the pagan antique. peace. The bodily-muscular impulse of M. of antiquity is opposed here by the ultimate detachment from the bodily-motor. moments and focusing on the meaning of the word (understood as “divine revelation”), on sublime reflection, immersion in contemplation, self-deepening. Therefore, in the choral music, everything that emphasizes the action is absent – the chased rhythm, the dimensionality of articulation, the activity of motives, the power of tonal gravity. Gregorian chant is a culture of absolute melodrama (“unity of hearts” is incompatible with “dissent”), which is not only alien to any chordal harmony, but does not allow any “polyphony” at all. The modal basis of the Gregorian M. – the so-called. church tones (four pairs of strictly diatonic modes, classified according to the characteristics of the finalis – the final tone, the ambitus and repercussion – the tone of repetition). Each of the modes, moreover, is associated with a certain group of characteristic motifs-chants (concentrated in the so-called psalmodic tones – toni psalmorum). The introduction of the tunes of a given mode into various musical instruments related to it, as well as melodic. variation in certain types of Gregorian chant, akin to the ancient principle of maqam. The poise of the line of choral melodies is expressed in its frequently occurring arcuate construction; the initial part of M. (initium) is an ascent to the tone of repetition (tenor or tuba; also repercussio), and the final part is a descent to the final tone (finalis). The rhythm of the chorale is not exactly fixed and depends on the pronunciation of the word. The relationship between text and music. beginning reveals two DOS. the type of their interaction: recitation, psalmody (lectio, orationes; accentue) and singing (cantus, modulatio; concentus) with their varieties and transitions. An example of a Gregorian M.:

Antiphon “Asperges me”, tone IV.

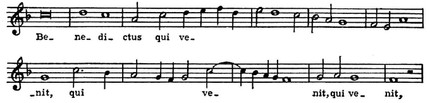

Melodika polyphonic. Renaissance schools partly relies on the Gregorian chant, but differs in a different range of figurative content (in connection with the aesthetics of humanism), a kind of intonation system, designed for polyphony. The pitch system is based on the old eight “church tones” with the addition of Ionian and Aeolian with their plagal varieties (the latter modes probably existed from the beginning of the era of European polyphony, but were recorded in theory only in the middle of the 16th century). The dominant role of diatonic in this era does not contradict the fact of systematic. the use of an introductory tone (musica ficta), sometimes aggravated (for example, in G. de Machaux), sometimes softening (in Palestrina), in some cases thickening to such an extent that it approaches the chromaticity of the 20th century. (Gesualdo, the end of the madrigal “Mercy!”). Despite the connection with polyphonic, chordal harmony, polyphonic. the melody is still conceived linearly (that is, it does not need harmonic support and allows any contrapuntal combinations). The line is built on the principle of a scale, not a triad; the monofunctionality of tones at a distance of a third is not manifested (or is revealed very weakly), the move to the diatonic. second is Ch. line development tool. The general contour of M. is floating and undulating, not showing a tendency to expressive injections; line type is predominantly non-culminating. Rhythmically, the sounds of M. are organized stably, unambiguously (which is already determined by the polyphonic warehouse, polyphony). However, the meter has a time-measuring value without any noticeable differentiation of the metric. close-up functions. Some details of the rhythm of the line and intervals are explained by the calculation for contrapunctuating voices (formulas of prepared retentions, syncopations, cambiates, etc.). With regard to the general melodic structure, as well as counterpoint, there is a significant tendency to prohibit repetitions (sounds, sound groups), deviations from which are allowed only as certain, provided for by musical rhetoric. prescriptions, jewelry M.; the goal of the ban is diversity (rule redicta, y by J. Tinktoris). Continuous renewal in music, especially characteristic of the polyphony of strict writing in the 15th and 16th centuries. (the so-called Prosamelodik; the term of G. Besseler), excludes the possibility of metric. and structural symmetry (periodicity) of the close-up, the formation of squareness, periods of classical. type and related forms.

Palestrina. “Missa brevis”, Benedictus.

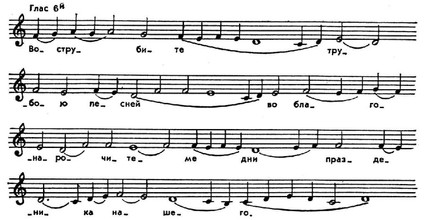

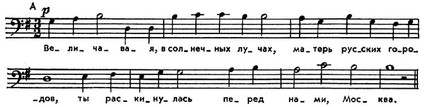

Old Russian melody. singer. art-va typologically represents a parallel to the Western Gregorian chant, but differs sharply from it in intonational content. Since originally borrowed from Byzantium M. were not firmly fixed, then already when they were transferred to Russian. soil, and even more so in the process of the seven-century existence of Ch. arr. in oral transmission (since the hook record before the 17th century. did not indicate the exact height of sounds) under the continuous influence of Nar. songwriting, they underwent a radical rethinking and, in the form that has come down to us (in the recording of the 17th century), undoubtedly turned into a purely Russian. phenomenon. The melodies of the old masters are a valuable cultural asset of the Russian. people. (“From the point of view of its musical content, ancient Russian cult melos is no less valuable than the monuments of ancient Russian painting,” noted B. AT. Asafiev.) The general basis of the modal system of Znamenny singing, at least from the 17th century. (cm. Znamenny chant), – the so-called. everyday scale (or everyday mode) GAH cde fga bc’d’ (out of four “accordions” of the same structure; the scale as a system is not an octave, but a fourth, it can be interpreted as four Ionian tetrachords, articulated in a fused way). Most M. classified according to belonging to one of the 8 voices. A voice is a collection of certain chants (there are several dozen of them in each voice), grouped around their melodies. tonic (2-3, sometimes more for most voices). Out-of-octave thinking is also reflected in the modal structure. М. may consist of a number of narrow-volume micro-scale formations within a single common scale. Line M. characterized by smoothness, the predominance of gamma, second movement, the avoidance of jumps within the construction (occasionally there are thirds and fourths). With the general soft nature of the expression (it should be “sung in a meek and quiet voice”) melodic. the line is strong and strong. Old Russian. cult music is always vocal and predominantly monophonic. Express. pronunciation of the text determines the rhythm of M. (highlighting stressed syllables in a word, moments important in meaning; at the end of M. ordinary rhythmic. cadence, ch. arr. with long durations). Measured rhythm is avoided, the close-up rhythm is regulated by the length and articulation of lines of text. The tunes vary. М. with the means available to her, she sometimes depicts those states or events that are mentioned in the text. All M. in general (and it can be very long) is built on the principle of variant development of tunes. The variance consists in a new singing with free repetition, withdrawal, addition of otd. sounds and whole sound groups (cf. example hymns and psalms). The skill of the chanter (composer) was manifested in the ability to create a long and varied M. from limited the number of underlying motives. The principle of originality was relatively strictly observed by Old Russian. masters of singing, the new line had to have a new tune (meloprose). Hence the great importance of variation in the broad sense of the word as a method of development. An example of ancient M.

Stichera for the Feast of the Vladimir Icon of the Mother of God, travel chant. Text and music (like) by Ivan the Terrible.

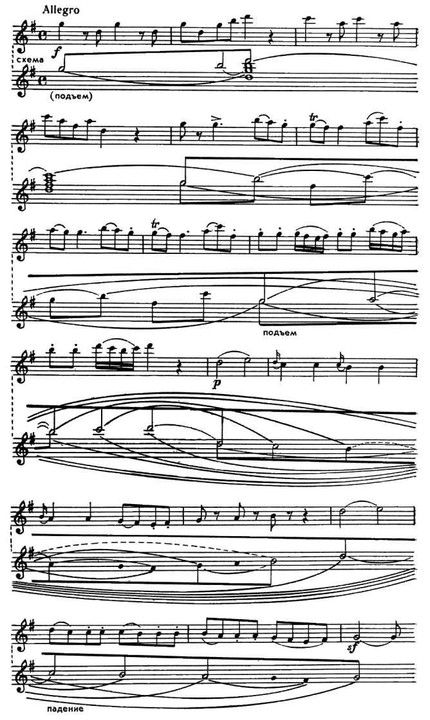

European melodic 17th-19th centuries is based on the major-minor tonal system and is organically connected with polyphonic fabric (not only in homophony, but also in polyphonic warehouse). “Melody can never appear in thought otherwise than together with harmony” (P. I. Tchaikovsky). M. continues to be the focus of thought, however, composing M., the composer (perhaps unconsciously) creates it together with the main. counterpoint (bass; according to P. Hindemith – “basic two-voice”), according to the harmony outlined in M.. The high development of music. thought is embodied in the phenomenon of melodic. structures due to the coexistence of genetics in it. layers, in a compressed form containing the previous forms of melodics:

1) primary linear-energy. element (in the form of the dynamics of ups and downs, the constructive backbone of the second line);

2) the metrorhythm factor that divides this element (in the form of a finely differentiated system of temporal relationships at all levels);

3) the modal organization of the rhythmic line (in the form of a richly developed system of tonal-functional connections; also at all levels of the musical whole).

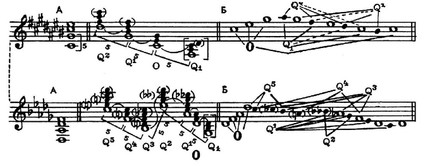

To all these layers of the structure, the last one is added – chord harmony, projected onto a one-voice line by using new, not only monophonic, but also polyphonic models for the construction of musical instruments. Compressed into a line, harmony tends to acquire its natural polyphonic form; therefore, the M. of the “harmonic” era is almost always born along with its own regenerated harmony – with a contrapuntal bass and filling middle voices. In the following example, based on the theme of the Cis-dur fugue from the 1st volume of the Well-Tempered Clavier by J.S. Bach and the theme from the fantasy overture Romeo and Juliet by P.I. Tchaikovsky, it is shown how chord harmony (A) becomes melodic a mode model (B), which, embodied in M., reproduces the harmony hidden in it (V; Q 1, Q2, Q3, etc. – chord functions of the first, second, third, etc. upper fifths; Q1 – respectively fifths down; 0 – “zero fifths”, tonic); analysis (by the method of reduction) ultimately reveals its central element (G):

Therefore, in the famous dispute between Rameau (who claimed that harmony shows the way to each of the voices, gives rise to a melody) and Rousseau (who believed that “melody in music is the same as drawing in painting; harmony is only the action of colors”) Rameau was right ; Rousseau’s formulation testifies to a misunderstanding of harmonics. the foundations of classical music and the confusion of concepts: “harmony” – “chord” (Rousseau would be right if “harmony” could be understood as accompanying voices).

The development of the European melodic “harmonic” era is a series of historical and stylistic. stages (according to B. Sabolchi, baroque, rococo, Viennese classics, romanticism), each of which is characterized by a specific complex. signs. Individual melodic styles of J. S. Bach, W. A. Mozart, L. Beethoven, F. Schubert, F. Chopin, R. Wagner, M. I. Glinka, P. I. Tchaikovsky, M. P. Mussorgsky. But one can also note certain general patterns of the melody of the “harmonic” era, due to the peculiarities of the dominant aesthetic. installations aimed at the most complete disclosure of internal. the world of the individual, human. personalities: the general, “earthly” character of expression (as opposed to a certain abstraction of the melody of the previous era); direct contact with the intonational sphere of everyday, folk music; permeation with rhythm and meter of dance, march, body movement; complex, branched metric organization with multilevel differentiation of light and heavy lobes; a strong shaping impulse from rhythm, motif, meter; metrorhythm. and motivic repetition as an expression of the activity of a sense of life; gravitation towards squareness, which becomes a structural reference point; triad and manifestation of harmonics. functions in M., hidden polyphony in the line, harmony implied and thought to M.; distinct monofunctionality of sounds perceived as parts of a single chord; on this basis, the internal reorganization of the line (for example, c – d – shift, c – d – e – externally, “quantitatively” further movement, but internally – a return to the previous consonance); a special technique for overcoming such delays in the development of the line by means of rhythm, motive development, harmony (see the example above, section B); the structure of a line, motif, phrase, theme is determined by the meter; metric dismemberment and periodicity are combined with dismemberment and periodicity of harmonics. structures in music (regular melodic cadences are especially characteristic); in connection with real (the theme from Tchaikovsky in the same example) or implied (the theme from Bach) harmony, the entire line of M. is distinctly (in the style of the Viennese classics even emphatically definitely) divided into chord and non-chord sounds, for example, in the theme from Bach gis1 at the beginning the first step – detention. The symmetry of form relations generated by the meter (that is, the mutual correspondence of parts) extends to large (sometimes very large) extensions, contributing to the creation of long-term developing and surprisingly integral meters (Chopin, Tchaikovsky).

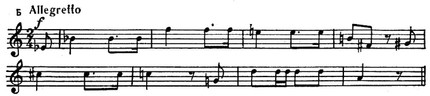

Melodika 20th century reveals a picture of great diversity – from the archaic of the most ancient layers of bunks. music (I. F. Stravinsky, B. Bartok), originality of non-European. music cultures (Negro, East Asian, Indian), mass, pop, jazz songs to modern tonal (S. S. Prokofiev, D. D. Shostakovich, N. Ya. Myaskovsky, A. I. Khachaturyan, R. S. Ledenev, R K. Shchedrin, B. I. Tishchenko, T. N. Khrennikov, A. N. Alexandrov, A. Ya. Stravinsky and others), new-modal (O. Messiaen, A. N. Cherepnin), twelve-tone, serial, serial music (A. Schoenberg, A. Webern, A. Berg, late Stravinsky, P. Boulez, L. Nono, D Ligeti, E. V. Denisov, A. G. Schnittke, R. K. Shchedrin, S. M. Slonimsky, K. A. Karaev and others), electronic, aleatoric (K. Stockhausen, V. Lutoslavsky and others .), stochastic (J. Xenakis), music with the technique of collage (L. Berio, C. E. Ives, A. G. Schnittke, A. A. Pyart, B. A. Tchaikovsky), and other even more extreme currents and directions. There can be no question of any general style and of any general principles of melody here; in relation to many phenomena, the very concept of melody is either not applicable at all, or should have a different meaning (for example, “timbre melody”, Klangfarbenmelodie – in the Schoenbergian or other sense). Samples of M. 20th century: purely diatonic (A), twelve-tone (B):

S. S. Prokofiev. “War and Peace”, Kutuzov’s aria.

D. D. Shostakovich. 14th symphony, movement V.

V. The beginnings of the doctrine of M. are contained in the works on music by Dr. Greece and Dr. East. Since the music of the ancient peoples is predominantly monophonic, the entire applied theory of music was essentially the science of music (“Music is the science of perfect melos” – Anonymous II Bellerman; “perfect”, or “full”, melos is the unity of the word, tune and rhythm). The same in means. least concerns the musicology of the European era. of the Middle Ages, in many respects, with the exception of most of the doctrine of counterpoint, also of the Renaissance: “Music is the science of melody” (Musica est peritia modulationis – Isidore of Seville). The doctrine of M. in the proper sense of the word dates back to the time when the muses. theory began to distinguish between harmonics, rhythms and melody as such. The founder of the doctrine of M. is considered to be Aristoxenus.

The ancient doctrine of music considers it as a syncretic phenomenon: “Melos has three parts: words, harmony, and rhythm” (Plato). The sound of the voice is common to music and speech. Unlike speech, melos is an interval-step movement of sounds (Aristoxenus); the movement of the voice is twofold: “one is called continuous and colloquial, the other interval (diastnmatikn) and melodic” (Anonymous (Cleonides), as well as Aristoxenus). Interval movement “permits delays (of sound at the same pitch) and intervals between them” alternating with each other. Transitions from one height to another are interpreted as due to muscular-dynamic. factors (“delays we call tensions, and the intervals between them – transitions from one tension to another. What produces a difference in tensions is tension and release” – Anonymous). The same Anonymous (Cleonides) classifies the types of melodic. movements: “there are four melodic turns with which the melody is performed: agogy, plok, petteia, tone. Agogue is the movement of the melody over the sounds following in order immediately one after the other (stepwise movement); ploke – the arrangement of sounds in intervals through a known number of steps (jumping movement); petteiya – repeated repetition of the same sound; tone – delaying sound for a longer time without interruption. Aristides Quintilian and Bacchius the Elder associate the movement of M. from higher to lower sounds with weakening, and in the opposite direction with amplification. According to Quintilian, M. are distinguished by ascending, descending, and rounded (wavy) patterns. In the era of antiquity, a regularity was noticed, according to which an upward jump (prolnpiz or prokroysiz) entails a return move down in seconds (analysis), and vice versa. M. are endowed with an expressive character (“ethos”). “As for melodies, they themselves contain the reproduction of characters” (Aristotle).

In the period of the Middle Ages and the Renaissance, the new in the doctrine of music was expressed primarily in the establishment of other relationships with the word, speech as the only legitimate ones. He sings so that not the voice of the one who sings, but the words please God ”(Jerome). “Modulatio”, understood not only as the actual M., melody, but also as pleasant, “consonant” singing and good construction of muses. the whole, produced by Augustine from the root modus (measure), is interpreted as “the science of moving well, that is, moving in compliance with the measure”, which means “observance of time and intervals”; the mode and consistency of the elements of rhythm and mode are also included in the concept of “modulation”. And since M. (“modulation”) comes from “measure”, then, in the spirit of neo-Pythagoreanism, Augustine considers the number to be the basis of beauty in M..

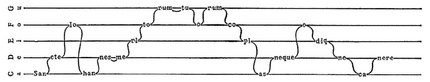

The rules of “convenient composition of melodies” (modulatione) in “Microlog” by Guido d’Arezzo b.ch. concern not so much melody in the narrow sense of the word (as opposed to rhythm, mode), but composition in general. “The expression of the melody should correspond to the subject itself, so that in sad circumstances the music should be serious, in calm circumstances it should be pleasant, in happy circumstances it should be cheerful, etc.” The structure of M. is likened to the structure of a verbal text: “just as in poetic meters there are letters and syllables, parts and stops, verses, so also in music (in harmonia) there are phthongs, that is, sounds that … are combined into syllables, and themselves (syllables ), simple and doubled, form a nevma, that is, part of the melody (cantilenae), ”, the parts are added to the department. Singing should be “as if measured in metrical footsteps.” M.’s departments, as in poetry, should be equal, and some should repeat each other. Guido points to possible ways of connecting the departments: “similarity in an ascending or descending melodic movement”, various kinds of symmetrical relationships: a repeating part of the M. can go “in a reverse movement and even in the same steps as it went when it first appeared”; the figure of M., emanating from the upper sound, is contrasted with the same figure emanating from the lower sound (“it is like how we, looking into the well, see the reflection of our face”). “The conclusions of phrases and sections should coincide with the same conclusions of the text, … the sounds at the end of the section should be, like a running horse, more and more slow, as if they were tired, with difficulty catching their breath.” Further, Guido – a medieval musician – offers a curious method of composing music, the so-called. the method of equivocalism, in which the pitch of M. is indicated by the vowel contained in the given syllable. In the following M., the vowel “a” always falls on the sound C (c), “e” – on the sound D (d), “i” – on E (e), “o” – on F (f) and “and » on G(g). (“The method is more pedagogical than composing,” notes K. Dahlhaus):

A prominent representative of the aesthetics of the Renaissance Tsarlino in the treatise “Establishments of Harmony”, referring to the ancient (Platonic) definition of M., instructs the composer to “reproduce the meaning (soggetto) contained in speech.” In the spirit of the ancient tradition, Zarlino distinguishes four principles in music, which together determine its amazing effect on a person, these are: harmony, meter, speech (oratione) and artistic idea (soggetto – “plot”); the first three of them are actually M. Comparing expresses. the possibilities of M. (in the narrow sense of the term) and rhythm, he prefers M. as having “greater power to change passions and morals from within.” Artusi (in “The Art of Counterpoint”) on the model of the ancient classification of melodic types. movement sets certain melodic. drawings. The interpretation of music as a representation of affect (in close connection with the text) comes into contact with its understanding on the basis of musical rhetoric, the more detailed theoretical development of which falls on the 17th and 18th centuries. Teachings about music of the new time already explore homophonic melody (the articulation of which is at the same time the articulation of the entire musical whole). However, only in Ser. 18th century you can meet the corresponding to its nature scientific and methodological. background. The dependence of homophonic music on harmony, emphasized by Rameau (“What we call a melody, that is, the melody of one voice, is formed by the diatonic order of sounds in conjunction with the fundamental succession and with all possible orders of harmonic sounds extracted from the “fundamental” ones) put before the theory music, the problem of the correlation of music and harmony, which for a long time determined the development of the theory of music. The study of music in the 17th-19th centuries. conducted b.h. not in works specially dedicated to her, but in works on composition, harmony, counterpoint. The theory of the Baroque era illuminates the structure of M. partly from the point of view of musical rhetoric. figures (particularly expressive turns of M. are explained as decorations of musical speech – some line drawings, various kinds of repetitions, exclamation motifs, etc.). From Ser. 18th century the doctrine of M. becomes what is now meant by this term. The first concept of the new doctrine of M. was formed in the books of I. Mattheson (1, 1737), J. Ripel (1739), K. Nickelman (1755). The problem of M. (in addition to the traditional musical-rhetorical premises, for example, in Mattheson), these German. theorists decide on the basis of the doctrine of meter and rhythm (“Taktordnung” by Ripel). In the spirit of enlightenment rationalism, Mattheson sees the essence of M. in the aggregate, first of all, its 1755 specific qualities: lightness, clarity, smoothness (fliessendes Wesen) and beauty (attractiveness – Lieblichkeit). To achieve each of these qualities, he recommends equally specific techniques. regulations. For example, to achieve smoothness, there are eight rules:

1) carefully monitor the uniformity of sound stops (Tonfüsse) and rhythm;

2) do not violate the geometric. ratios (Verhalt) of certain similar parts (Sdtze), namely numerum musicum (musical numbers), i.e. accurately observe melodic. numerical proportions (Zahlmaasse);

3) the less internal conclusions (förmliche Schlüsse) in M., the smoother it is, etc. The merit of Rousseau is that he sharply emphasized the meaning of melodic. intonation (“Melody … imitates the intonations of the language and those turns that in each dialect correspond to certain mental movements”).

Closely adjacent to the teachings of the 18th century. A. Reich in his “Treatise on Melody” and A. B. Marx in “The Doctrine of Musical Composition”. They worked out in detail the problems of structural division. Reich defines music from two sides—aesthetic (“Melody is the language of feeling”) and technical (“Melody is the succession of sounds, as harmony is the succession of chords”) and analyzes in detail the period, sentence (membre), phrase (dessin mélodique), “ theme or motif” and even feet (pieds mélodiques)—trocheus, iambic, amphibrach, etc. Marx wittily formulates the semantic meaning of the motif: “Melody must be motivated.”

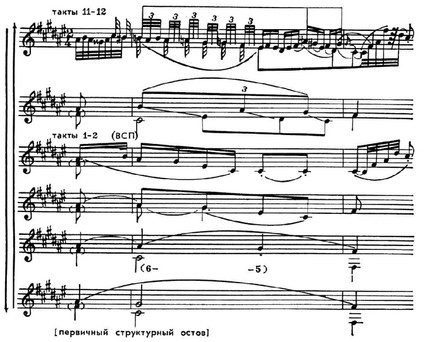

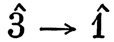

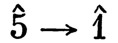

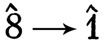

X. Riemann understands M. as the totality and interaction of all fundamentals. means of music – harmony, rhythm, beat (meter) and tempo. In constructing the scale, Riemann proceeds from the scale, explaining each of its sounds through chord successions, and proceeds to the tonal connection, which is determined by the relation to the center. chord, then successively adds a rhythm, melodic. decorations, articulation through cadenzas and, finally, comes from motives to sentences and further to large forms (according to the “Teaching about Melody” from volume l of the “Great Teaching about Composition”). E. Kurt emphasized with particular force the characteristic tendencies of the 20th-century teaching about music, opposing the understanding of chord harmony and time-measured rhythm as the foundations of music. In contrast, he put forward the idea of the energy of linear movement, which is most directly expressed in music, but hidden (in the form of “potential energy”) existing in a chord, harmony. G. Schenker saw in M., first of all, a movement striving towards a specific goal, regulated by the relations of harmony (mainly 3 types – “primary lines”

,

и

; all three point downward). On the basis of these “primary lines”, branch lines “bloom”, from which, in turn, shoot lines “sprout”, etc. P. Hindemith’s theory of melody is similar to Schenker’s (and not without its influence) (M.’s wealth is in intersecting various second moves, provided that the steps are tonal-connected). A number of manuals outline the theory of dodecaphone melody (a special case of this technique).

In Russian theoretical in literature, the first special work “On Melody” was written by I. Gunke (1859, as the 1st section of the “Complete Guide to Composing Music”). In terms of his general attitudes, Gunke is close to the Reich. The metrorhythm is taken as the basis of music (the opening words of the Guide: “Music is invented and composed according to measures”). M.’s content within one cycle called. a clock motif, the figures inside the motifs are models or drawings. The study of M. to a large extent accounts for the works that explore folklore, ancient and eastern. music (D. V. Razumovsky, A. N. Serov, P. P. Sokalsky, A. S. Famintsyn, V. I. Petr, V. M. Metallov; in Soviet times – M. V. Brazhnikov, V. M. Belyaev, N. D. Uspensky and others).

I. P. Shishov (in the 2nd half of the 1920s he taught a course in melody at the Moscow Conservatory) takes other Greek. the principle of temporal division of M. (which was also developed by Yu. N. Melgunov): the smallest unit is mora, mora are combined into stops, those into pendants, pendants into periods, periods into stanzas. Form M. obeys b.ch. symmetry law (explicit or hidden). The method of analysis of speech involves taking into account all the intervals formed by the movement of the voice and the correspondence relations of parts that arise in music. L. A. Mazel in the book “On Melody” considers M. in the interaction of the main. will express. means of music – melodic. lines, mode, rhythm, structural articulation, gives essays on the historical. development of music (from J. S. Bach, L. Beethoven, F. Chopin, P. I. Tchaikovsky, S. V. Rachmaninov, and some Soviet composers). M. G. Aranovsky and M. P. Papush in their works raise the question of the nature of M. and the essence of the concept of M.

References: Gunke I., The doctrine of melody, in the book: A complete guide to composing music, St. Petersburg, 1863; Serov A., Russian folk song as a subject of science, “Music. season”, 1870-71, No 6 (section 2 – Technical warehouse of the Russian song); the same, in his book: Selected. articles, vol. 1, M.-L., 1950; Petr V.I., On the melodic warehouse of the Aryan song. Historical and Comparative Experience, SPV, 1899; Metallov V., Osmosis of the Znamenny Chant, M., 1899; Küffer M., Rhythm, melody and harmony, “RMG”, 1900; Shishov IP, On the question of the analysis of melodic structure, “Musical education”, 1927, No 1-3; Belyaeva-Kakzemplyarskaya S., Yavorsky V., Structure of a melody, M., 1929; Asafiev B. V., Musical form as a process, book. 1-2, M.-L., 1930-47, L., 1971; his own, Speech intonation, M.-L., 1965; Kulakovsky L., On the methodology of melody analysis, “SM”, 1933, No 1; Gruber R. I., History of musical culture, vol. 1, part 1, M.-L., 1941; Sposobin I. V., Musical form, M.-L., 1947, 1967; Mazel L. A., O melody, M., 1952; Ancient musical aesthetics, entry. Art. and coll. texts by A. F. Losev, Moscow, 1960; Belyaev V. M., Essays on the history of music of the peoples of the USSR, vol. 1-2, M., 1962-63; Uspensky N. D., Old Russian singing art, M., 1965, 1971; Shestakov V.P. (comp.), Musical aesthetics of the Western European Middle Ages and Renaissance, M., 1966; his, Musical aesthetics of Western Europe of the XVII-XVIII centuries, M., 1971; Aranovsky M. G., Melodika S. Prokofiev, L., 1969; Korchmar L., The doctrine of melody in the XVIII century, in collection: Questions of the theory of music, vol. 2, M., 1970; Papush MP, On the analysis of the concept of melody, in: Musical Art and Science, vol. 2, M., 1973; Zemtsovsky I., Melodika of calendar songs, L., 1975; Plato, State, Works, trans. from ancient Greek A. Egunova, vol. 3, part 1, M., 1971, p. 181, § 398d; Aristotle, Politics, trans. from ancient Greek S. Zhebeleva, M., 1911, p. 373, §1341b; Anonymous (Cleonides?), Introduction to the harmonica, trans. from ancient Greek G. Ivanova, “Philological Review”, 1894, v. 7, book. one.

Yu. N. Kholopov