Lev Nikolaevich Oborin |

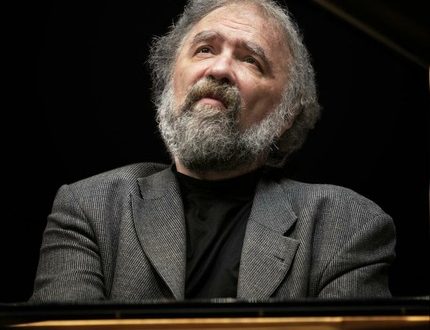

Lev Oborin

Lev Nikolaevich Oborin was the first Soviet artist to win the first victory in the history of Soviet musical performing arts at an international competition (Warsaw, 1927, Chopin Competition). Today, when the ranks of winners of various musical tournaments march one after another, when new names and faces are constantly appearing in them, with whom “there are no numbers”, it is difficult to fully appreciate what Oborin did 85 years ago. It was a triumph, a sensation, a feat. Discoverers are always surrounded with honor – in space exploration, in science, in public affairs; Oborin opened the road, which J. Flier, E. Gilels, J. Zak and many others followed with brilliance. Winning first prize in a serious creative competition is always difficult; in 1927, in the atmosphere of ill will that prevailed in bourgeois Poland in relation to Soviet artists, Oborin was doubly, triply difficult. He did not owe his victory to a fluke or something else – he owed it exclusively to himself, to his great and extremely charming talent.

- Piano music in the Ozon online store →

Oborin was born in Moscow, in the family of a railway engineer. The boy’s mother, Nina Viktorovna, loved to spend time at the piano, and his father, Nikolai Nikolaevich, was a great music lover. From time to time, impromptu concerts were arranged at the Oborins: one of the guests sang or played, Nikolai Nikolayevich in such cases willingly acted as an accompanist.

The first teacher of the future pianist was Elena Fabianovna Gnesina, well known in musical circles. Later, at the conservatory, Oborin studied with Konstantin Nikolaevich Igumnov. “It was a deep, complex, peculiar nature. In some ways, it’s unique. I think that attempts to characterize Igumnov’s artistic individuality with the help of one or two terms or definitions – be it “lyricist” or something else of the same kind – are generally doomed to failure. (And the young people of the Conservatory, who know Igumnov only from single recordings and from individual oral testimonies, are sometimes inclined to such definitions.)

To tell the truth, – continued the story about his teacher Oborin, – Igumnov was not always even, as a pianist. Perhaps best of all he played at home, in the circle of loved ones. Here, in a familiar, comfortable environment, he felt at ease and at ease. He played music at such moments with inspiration, with genuine enthusiasm. In addition, at home, on his instrument, everything always “came out” for him. In the conservatory, in the classroom, where sometimes a lot of people gathered (students, guests …), he “breathed” at the piano no longer so freely. He played here quite a lot, although, to be honest, he did not always and not always succeed in everything equally well. Igumnov used to show the work studied with the student not from beginning to end, but in parts, fragments (those that were currently in work). As for his speeches to the general public, it was never possible to predict in advance what this performance was destined to become.

There were amazing, unforgettable clavirabends, spiritualized from the first to the last note, marked by the subtlest penetration into the soul of music. And along with them there were uneven performances. Everything depended on the minute, on the mood, on whether Konstantin Nikolayevich managed to control his nerves, overcome his excitement.

Contacts with Igumnov meant a lot in the creative life of Oborin. But not only them. The young musician was generally, as they say, “lucky” with teachers. Among his conservatory mentors was Nikolai Yakovlevich Myaskovsky, from whom the young man took composition lessons. Oborin did not have to become a professional composer; later life simply did not leave him such an opportunity. However, creative studies at the time of study gave the famous pianist a lot – he emphasized this more than once. “Life has turned out in such a way,” he said, that in the end I happened to become an artist and teacher, and not a composer. However, now resurrecting my younger years in my memory, I often wonder how beneficial and useful these attempts to compose were then for me. The point is not only that by “experimenting” at the keyboard, I deepened my understanding of the expressive properties of the piano, but by creating and practicing various texture combinations on my own, in general, I progressed as a pianist. By the way, I had to study a lot – not to learn my plays, just as Rachmaninov, for example, did not teach them, I couldn’t …

And yet the main thing is different. When, putting aside my own manuscripts, I took on other people’s music, the works of other authors, the form and structure of these works, their internal structure and the very organization of sound material became somehow much clearer to me. I noticed that then I began to delve into the meaning of complex intonation-harmonic transformations, the logic of the development of melodic ideas, etc. in a much more conscious way. creating music rendered me, the performer, invaluable services.

One curious incident from my life often comes to mind to me,” Oborin concluded the conversation about the benefits of composing for performers. “Somehow in the early thirties I was invited to visit Alexei Maksimovich Gorky. I must say that Gorky was very fond of music and felt it subtly. Naturally, at the request of the owner, I had to sit down at the instrument. I then played a lot and, it seems, with great enthusiasm. Aleksey Maksimovich listened attentively, resting his chin on the palm of his hand and never taking his intelligent and kind eyes from me. Unexpectedly, he asked: “Tell me, Lev Nikolaevich, why don’t you compose music yourself?” No, I answer, I used to be fond of it, but now I just have no time – traveling, concerts, students … “It’s a pity, it’s a pity,” says Gorky, “if the gift of a composer is already inherent in you by nature, it must be protected – it’s a huge value. Yes, and in performance, probably, it would help you a lot … ”I remember that I, a young musician, were deeply struck by these words. Do not say anything – wisely! He, a man so far from music, so quickly and correctly grasped the very essence of the problem – performer-composer».

The meeting with Gorky was only one in a series of many interesting meetings and acquaintances that befell Oborin in the XNUMXs and XNUMXs. At that time he was in close contact with Shostakovich, Prokofiev, Shebalin, Khachaturian, Sofronitsky, Kozlovsky. He was close to the world of the theater – to Meyerhold, to the “MKhAT”, and especially to Moskvin; with some of those named above, he had a strong friendship. Subsequently, when Oborin becomes a renowned master, criticism will write with admiration about internal culture, invariably inherent in his game, that in him you can feel the charm of intelligence in life and on stage. Oborin owed this to his happily formed youth: family, teachers, fellow students; once in a conversation, he said that he had an excellent “nutrient environment” in his younger years.

In 1926, Oborin brilliantly graduated from the Moscow Conservatory. His name was engraved in gold on the famous marble Board of Honor that adorns the foyer of the Small Hall of the Conservatory. This happened in the spring, and in December of the same year, a prospectus for the First International Chopin Piano Competition in Warsaw was received in Moscow. Musicians from the USSR were invited. The problem was that there was virtually no time left to prepare for the competition. “Three weeks before the start of the competition, Igumnov showed me the competition program,” Oborin later recalled. “My repertoire included about a third of the mandatory competition program. Training under such conditions seemed pointless.” Nevertheless, he began to prepare: Igumnov insisted and one of the most authoritative musicians of that time, B. L. Yavorsky, whose opinion Oborin considered to the highest degree. “If you really want to, then you can speak,” Yavorsky told Oborin. And he believed.

In Warsaw, Oborin showed himself extremely well. He was unanimously awarded the first prize. The foreign press, not hiding its surprise (it was already said above: it was 1927), spoke enthusiastically about the performance of the Soviet musician. The well-known Polish composer Karol Szymanowski, giving an assessment of Oborin’s performance, uttered the words that newspapers of many countries of the world bypassed at one time: “A phenomenon! It is not a sin to worship him, for he creates Beauty.

Returning from Warsaw, Oborin begins an active concert activity. It is on the rise: the geography of his tours is expanding, the number of performances is increasing (the composition has to be abandoned – there is not enough time or energy). Oborin’s concert work developed especially widely in the post-war years: in addition to the Soviet Union, he plays in the USA, France, Belgium, Great Britain, Japan, and in many other countries. Only illness interrupts this non-stop and rapid flow of tours.

… Those who remember the pianist at the time of the thirties unanimously speak of the rare charm of his playing – artless, full of youthful freshness and immediacy of feelings. I. S. Kozlovsky, talking about the young Oborin, writes that he struck with “lyricism, charm, human warmth, some kind of radiance.” The word “radiance” attracts attention here: expressive, picturesque and figurative, it helps to understand a lot in the appearance of a musician.

And one more bribed in it – simplicity. Perhaps the Igumnov school had an effect, perhaps the features of Oborin’s nature, the make-up of his character (most likely both), – only there was in him, as an artist, amazing clarity, lightness, integrity, inner harmony. This made an almost irresistible impression on the general public, and on the pianist’s colleagues as well. In Oborin, the pianist, they felt something that went back to the distant and glorious traditions of Russian art – they really determined a lot in his concert performance style.

A large place in its programs was occupied by the works of Russian authors. He wonderfully played The Four Seasons, Dumka and Tchaikovsky’s First Piano Concerto. One could often hear Mussorgsky’s Pictures at an Exhibition, as well as Rachmaninov’s works – the Second and Third Piano Concertos, preludes, etudes-pictures, Musical Moments. It is impossible not to recall, touching on this part of Oborin’s repertoire, and his enchanting performance of Borodin’s “Little Suite”, Lyadov’s Variations on a Theme by Glinka, Concerto for Piano and Orchestra, Op. 70 A. Rubinstein. He was an artist of a truly Russian fold – in his character, appearance, attitude, artistic tastes and affections. It was simply impossible not to feel all this in his art.

And one more author must be named when speaking about Oborin’s repertoire – Chopin. He played his music from the first steps on the stage until the end of his days; he once wrote in one of his articles: “The feeling of joy that pianists have Chopin never leaves me.” It is difficult to remember everything that Oborin played in his Chopin programs – etudes, preludes, waltzes, nocturnes, mazurkas, sonatas, concertos and much more. It’s hard to enumerate that he played, it’s even harder to give a performance today, as he did it. “His Chopin – crystal clear and bright – undividedly captured any audience,” J. Flier admired. It is no coincidence, of course, that Oborin experienced his first and greatest creative triumph in his life at a competition dedicated to the memory of the great Polish composer.

… In 1953, the first performance of the duet Oborin – Oistrakh took place. A few years later, a trio was born: Oborin – Oistrakh – Knushevitsky. Since then, Oborin has become known to the musical world not only as a soloist, but also as a first-class ensemble player. From a young age he loved chamber music (even before meeting his future partners, he played in a duet with D. Tsyganov, performed together with the Beethoven Quartet). Indeed, some features of Oborin’s artistic nature – performing flexibility, sensitivity, the ability to quickly establish creative contacts, stylistic versatility – made him an indispensable member of duets and trios. On the account of Oborin, Oistrakh and Knushevitsky, there was a huge amount of music replayed by them – works by classics, romantics, modern authors. If we talk about their pinnacle achievements, then one cannot fail to name the Rachmaninoff cello sonata interpreted by Oborin and Knushevitsky, as well as all ten Beethoven sonatas for violin and piano, performed at one time by Oborin and Oistrakh. These sonatas were performed, in particular, in 1962 in Paris, where Soviet artists were invited by a well-known French record company. Within a month and a half, they captured their performance on records, and also – in a series of concerts – introduced him to the French public. It was a difficult time for the illustrious duo. “We really worked hard and hard,” D. F. Oistrakh later said, “we didn’t go anywhere, we refrained from tempting walks around the city, refusing numerous hospitable invitations. Returning to Beethoven’s music, I wanted to rethink the general plan of the sonatas once again (which counts!) and relive every detail. But it is unlikely that the audience, having visited our concerts, got more pleasure than we did. We enjoyed every evening when we played sonatas from the stage, we were infinitely happy, listening to the music in the silence of the studio, where all the conditions were created for this.”

Along with everything else, Oborin also taught. From 1931 until the last days of his life, he headed a crowded class at the Moscow Conservatory – he raised more than a dozen students, among whom many famous pianists can be named. As a rule, Oborin actively toured: traveled to various cities of the country, spent a long time abroad. It so happened that his meetings with students were not too frequent, not always systematic and regular. This, of course, could not but leave a certain imprint on the classes in his class. Here one did not have to count on everyday, caring pedagogical care; to many things, the “Oborints” had to find out on their own. There were, apparently, in such an educational situation both their pluses and minuses. It’s about something else now. Infrequent meetings with the teacher somehow especially highly valued his pets – that’s what I would like to emphasize. They were valued, perhaps, more than in the classes of other professors (even if they were no less eminent and deserved, but more “domestic”). These meeting-lessons with Oborin were an event; prepared for them with special care, waited for them, it happened, almost like a holiday. It is difficult to say whether there was a fundamental difference for a student of Lev Nikolayevich in performing, say, in the Small Hall of the Conservatory at any of the student evenings or playing a new piece for his teacher, learned in his absence. This heightened feeling Liability before the show in the classroom was a kind of stimulant – potent and very specific – in the classes with Oborin. He determined a lot in the psychology and educational work of his wards, in his relationship with the professor.

There is no doubt that one of the main parameters by which one can and should judge the success of teaching is related to authority teacher, a measure of his professional prestige in the eyes of students, the degree of emotional and volitional influence on his pupils. Oborin’s authority in the class was indisputably high, and his influence on young pianists was exceptionally strong; this alone was enough to speak of him as a major pedagogical figure. People who closely communicated with him recall that a few words dropped by Lev Nikolaevich turned out to be sometimes more weighty and significant than other most magnificent and flowery speeches.

A few words, it must be said, were generally preferable to Oborin than lengthy pedagogical monologues. Rather a little closed than overly sociable, he was always rather laconic, stingy with statements. All kinds of literary digressions, analogies and parallels, colorful comparisons and poetic metaphors – all this was the exception in his lessons rather than the rule. Speaking about the music itself – its character, images, ideological and artistic content – he was extremely concise, precise and strict in expressions. There was never anything superfluous, optional, leading away in his statements. There is a special kind of eloquence: to say only what is relevant, and nothing more; in this sense, Oborin was really eloquent.

Lev Nikolaevich was especially brief at rehearsals, a day or two before the performance, the upcoming pupil of his class. “I’m afraid to disorient the student,” he once said, “at least in some way to shake his faith in the established concept, I’m afraid to“ frighten off ”the lively performing feeling. In my opinion, it is best for a teacher in the pre-concert period not to teach, not to instruct a young musician again and again, but simply to support, cheer him up … “

Another characteristic moment. Oborin’s pedagogical instructions and remarks, always specific and purposeful, were usually addressed to what was connected with practical side in pianism. With performance as such. How, for example, to play this or that difficult place, simplifying it as much as possible, making it technically easier; what fingering might be most suitable here; what position of the fingers, hands and body would be the most convenient and appropriate; what tactile sensations would lead to the desired sound, etc. – these and similar questions most often came to the forefront of Oborin’s lesson, determining its special constructiveness, rich “technological” content.

It was exceptionally important for the students that everything that Oborin spoke about was “provided” – as a kind of gold reserve – by his vast professional performing experience, based on knowledge of the most intimate secrets of the pianistic “craft”.

How, say, to perform a piece with the expectation of its future sound in the concert hall? How to correct sound production, nuance, pedalization, etc. in this regard? Advice and recommendations of this kind came from the master, many times and, most importantly, personally who tested it all in practice. There was a case when, at one of the lessons that took place at Oborin’s house, one of his students played Chopin’s First Ballade. “Well, well, not bad,” summed up Lev Nikolayevich, having listened to the work from beginning to end, as usual. “But this music sounds too chamber, I would even say “room-like”. And you are going to perform in the Small Hall… Did you forget about that? Please start again and take this into account … “

This episode brings to mind, by the way, one of Oborin’s instructions, which was repeatedly repeated to his students: a pianist playing from the stage must have a clear, intelligible, very articulate “reprimand” – “well-placed performing diction,” as Lev Nikolayevich put it on one of the classes. And therefore: “More embossed, larger, more definite,” he often demanded at rehearsals. “A speaker speaking from the podium will speak differently than face to face with his interlocutor. The same is true for a concert pianist playing in public. The whole hall should hear it, and not just the first rows of the stalls.

Perhaps the most potent tool in the arsenal of Oborin the teacher has long been show (illustration) on the instrument; only in recent years, due to illness, Lev Nikolaevich began to approach the piano less often. In terms of its “working” priority, in terms of its effectiveness, the method of display, one might say, excelled in comparison with the verbal explanatory one. And it’s not even that a specific demonstration on the keyboard of one or another performing technique helped the “Oborints” in their work on sound, technique, pedalization, etc. Shows-illustrations of the teacher, a live and close example of his performance – all this carried with is something more substantial. Playing Lev Nikolaevich on the second instrument inspired musical youth, opened up new, previously unknown horizons and perspectives in pianism, allowed them to breathe in the exciting aroma of a large concert stage. This game sometimes woke up something similar to “white envy”: after all, it turns out that as и that can be done on the piano… It used to be that showing one or another work on the Oborinsky piano brought clarity to the most difficult situations for the student to perform, cut the most intricate “Gordian knots”. In the memoirs of Leopold Auer about his teacher, the wonderful Hungarian violinist J. Joachim, there are lines: so!” accompanied by a reassuring smile.” (Auer L. My school of playing the violin. – M., 1965. S. 38-39.). Similar scenes often took place in the Oborinsky class. Some pianistically complex episode was played, a “standard” was shown – and then a summary of two or three words was added: “In my opinion, so …”

… So, what did Oborin ultimately teach? What was his pedagogical “credo”? What was the focus of his creative activity?

Oborin introduced his students to a truthful, realistic, psychologically convincing transmission of the figurative and poetic content of music; this was the alpha and omega of his teaching. Lev Nikolayevich could talk about different things in his lessons, but all this eventually led to one thing: to help the student to understand the innermost essence of the composer’s intention, to realize it with his mind and heart, to enter into “co-authorship” with the music creator, to embody his ideas with maximum conviction and persuasiveness. “The fuller and deeper the performer understands the author, the greater the chance that in the future they will believe the performer himself,” he repeatedly expressed his point of view, sometimes varying the wording of this thought, but not its essence.

Well, to understand the author – and here Lev Nikolayevich spoke in full agreement with the school that raised him, with Igumnov – meant in the Oborinsky class to decipher the text of the work as carefully as possible, to “exhaust” it completely and to the bottom, to reveal not only the main thing in musical notation, but also the most subtle nuances of composer’s thought, fixed in it. “Music, depicted by signs on music paper, is a sleeping beauty, it still needs to be disenchanted,” he once said in a circle of students. As far as textual accuracy was concerned, Lev Nikolayevich’s requirements for his pupils were the most strict, not to say pedantic: nothing approximate in the game, done hastily, “in general”, without proper thoroughness and accuracy, was forgiven. “The best player is the one who conveys the text more clearly and logically,” these words (they are attributed to L. Godovsky) could serve as an excellent epigraph to many of Oborin’s lessons. Any sins against the author – not only against the spirit, but also against the letters of the interpreted works – were regarded here as something shocking, as a performer’s bad manners. With all his appearance, Lev Nikolaevich expressed extreme displeasure in such situations …

Not a single seemingly insignificant textured detail, not a single hidden echo, slurred note, etc., escaped his professionally keen eye. Highlight with auditory attention all и all in an interpreted work, Oborin taught, the essence is to “recognize”, to comprehend a given work. “For a musician hear – means understand“, – he dropped in one of the lessons.

There is no doubt that he appreciated the manifestations of individuality and creative independence in young pianists, but only to the extent that these qualities contributed to the identification objective regularities musical compositions.

Accordingly, the requirements of Lev Nikolaevich for the game of students were determined. A musician of strict, one might say, purist taste, somewhat academic at the time of the fifties and sixties, he resolutely opposed subjectivist arbitrariness in performance. Everything that was excessively catchy in the interpretations of his young colleagues, claiming to be unusual, shocking with outward originality, was not without prejudice and wariness. So, once talking about the problems of artistic creativity, Oborin recalled A. Kramskoy, agreeing with him that “originality in art from the first steps is always somewhat suspicious and rather indicates narrowness and limitation than wide and versatile talent. A deep and sensitive nature at the beginning cannot but be carried away by everything that has been done good before; such natures imitate … “

In other words, what Oborin sought from his students, wanting to hear in their game, could be characterized in terms of: simple, modest, natural, sincere, poetic. Spiritual exaltation, somewhat exaggerated expression in the process of making music – all this usually jarred Lev Nikolayevich. He himself, as was said, both in life and on stage, at the instrument, was restrained, balanced in feelings; approximately the same emotional “degree” appealed to him in the performance of other pianists. (Somehow, having listened to the too temperamental play of one debuting artist, he remembered the words of Anton Rubinstein that there should not be a lot of feelings, a feeling can only be in moderation; if there is a lot of it, then it is false …) Consistency and correctness in emotional manifestations , inner harmony in poetics, perfection of technical execution, stylistic accuracy, rigor and purity – these and similar performance qualities evoked Oborin’s invariably approving reaction.

What he cultivated in his class could be defined as an elegant and subtle musical professional education, instilling impeccable performing manners in his students. At the same time, Oborin proceeded from the conviction that “a teacher, no matter how knowledgeable and experienced he may be, cannot make a student more talented than he is by nature. It will not work, no matter what is done here, no matter what pedagogical tricks are used. The young musician has a real talent – sooner or later it will make itself known, it will break out; no, there is nothing to help here. It is another matter that it is always necessary to lay a solid foundation of professionalism under young talent, no matter how large it is measured; introduce him to the norms of good behavior in music (and maybe not only in music). There is already a direct duty and duty of the teacher.

In such a view of things, there was great wisdom, a calm and sober awareness of what a teacher can do and what is beyond his control …

Oborin served for many years as an inspiring example, a high artistic model for his younger colleagues. They learned from his art, imitated him. Let us repeat, his victory in Warsaw stirred up many of those who later followed him. It is unlikely that Oborin would have played this leading, fundamentally important role in Soviet pianism, if not for his personal charm, his purely human qualities.

This is always given considerable importance in professional circles; hence, in many respects, the attitude towards the artist, and the public resonance of his activities. “There was no contradiction between Oborin the artist and Oborin the man,” wrote Ya. I. Zak, who knew him closely. “He was very harmonious. Honest in art, he was impeccably honest in life… He was always friendly, benevolent, truthful and sincere. He was a rare unity of aesthetic and ethical principles, an alloy of high artistry and the deepest decency. (Zak Ya. Bright talent / / L. N. Oborin: Articles. Memoirs. – M., 1977. P. 121.).

G. Tsypin