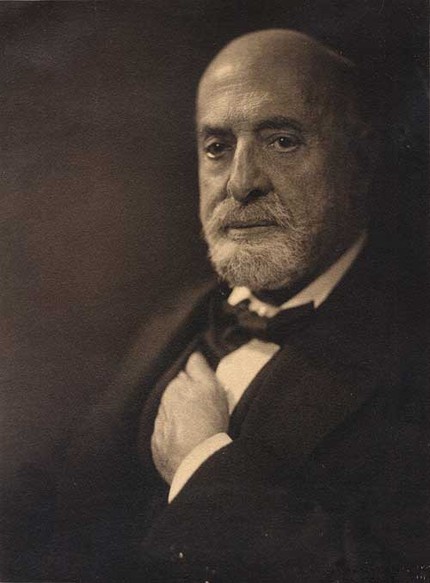

Leopold Auer |

Leopold Auer

Auer tells a lot of interesting things about his life in his book Among Musicians. Written already in his declining years, it does not differ in documentary accuracy, but allows you to look into the creative biography of its author. Auer is a witness, an active participant and a subtle observer of the most interesting era in the development of Russian and world musical culture in the second half of the XNUMXth century; he was the spokesman for many of the progressive ideas of the era and remained faithful to its precepts to the end of his days.

Auer was born on June 7, 1845 in the small Hungarian town of Veszprem, in the family of an artisan painter. The boy’s studies began at the age of 8, at the Budapest Conservatory, in the class of Professor Ridley Cone.

Auer does not write a word about his mother. A few colorful lines are dedicated to her by the writer Rachel Khin-Goldovskaya, a close friend of Auer’s first wife. From her diaries we learn that Auer’s mother was an inconspicuous woman. Later, when her husband died, she maintained a haberdashery shop, on the income from which she subsisted modestly.

Auer’s childhood was not easy, the family often experienced financial difficulties. When Ridley Cone gave his student a debut at a big charity concert at the National Opera (Auer performed Mendelssohn’s Concerto), patrons became interested in the boy; with their support, the young violinist got the opportunity to enter the Vienna Conservatory to the famous professor Yakov Dont, to whom he owed his violin technique. At the conservatory, Auer also attended a quartet class led by Joseph Helmesberger, where he learned the solid foundations of his chamber style.

However, funds for education soon dried up, and after 2 years of studies, in 1858 he regretfully left the conservatory. From now on, he becomes the main breadwinner of the family, so he has to give concerts even in the provincial towns of the country. The father took over the duties of an impresario, they found a pianist, “as needy as ourselves, who was ready to share our miserable table and shelter with us,” and began to lead the life of itinerant musicians.

“We were constantly shivering from rain and snow, and I often let out a sigh of relief at the sight of the bell tower and the roofs of the city, which was supposed to shelter us after a weary journey.”

This went on for 2 years. Perhaps Auer would never have got out of the position of a small provincial violinist, if not for a memorable meeting with Vieuxtan. Once, having stopped in Graz, the main city of the province of Styria, they learned that Viettan had come here and was giving a concert. Auer was impressed by Viet Tang’s playing, and his father made a thousand efforts to make the great violinist listen to his son. At the hotel they were received very kindly by Vietang himself, but very coldly by his wife.

Let us leave the floor to Auer himself: “Ms. Vietang sat down at the piano with an undisguised expression of boredom on her face. Nervous by nature, I began to play “Fantaisie Caprice” (a work by Vieux. – L. R.), all trembling with excitement. I don’t remember how I played, but it seems to me that I put my whole soul into every note, although my underdeveloped technique was not always up to the task. Viettan cheered me up with his friendly smile. Suddenly, at the very moment when I had reached the middle of a cantabile phrase, which, I confess, I played too sentimentally, Madame Vietang jumped up from her seat and began to pace the room quickly. Bending down to the very floor, she looked in all corners, under the furniture, under the table, under the piano, with the preoccupied air of a man who has lost something and cannot find it in any way. Interrupted so unexpectedly by her strange act, I stood with my mouth wide open, wondering what all this could mean. No less surprised himself, Vieuxtan followed his wife’s movements with astonishment and asked her what she was looking for with such anxiety under the furniture. “It’s like cats are hiding somewhere here in the room,” she said, their meows coming from every corner. She hinted at my overly sentimental glissando in a cantabile phrase. From that day on, I hated every glissando and vibrato, and until this very moment I can’t remember without a shudder my visit to Viettan.”

However, this meeting turned out to be significant, forcing the young musician to treat himself more responsibly. From now on, he saves money to continue his education, and sets himself the goal of getting to Paris.

They approach Paris slowly, giving concerts in the cities of Southern Germany and Holland. Only in 1861 did father and son reach the French capital. But here Auer suddenly changed his mind and, on the advice of his compatriots, instead of entering the Paris Conservatory, he went to Hannover to Joachim. Lessons from the famous violinist lasted from 1863 to 1864 and, despite their short duration, had a decisive impact on Auer’s subsequent life and work.

After graduating from the course, Auer went to Leipzig in 1864, where he was invited by F. David. A successful debut in the famous Gewandhaus hall opens up bright prospects for him. He signs a contract for the post of concertmaster of the orchestra in Düsseldorf and works here until the start of the Austro-Prussian war (1866). For some time, Auer moved to Hamburg, where he performed the functions of orchestra accompanist and quartetist, when he suddenly received an invitation to take the place of first violinist in the world-famous Müller Brothers Quartet. One of them fell ill, and in order not to lose concerts, the brothers were forced to turn to Auer. He played in the Muller quartet until his departure to Russia.

The circumstance that served as the immediate reason for inviting Auer to St. Petersburg was a meeting with A. Rubinstein in May 1868 in London, where they first played in a series of chamber concerts organized by the London society MusicaI Union. Obviously, Rubinstein immediately noticed the young musician, and a few months later, the then director of the St. Petersburg Conservatory N. Zaremba signed a 3-year contract with Auer for the position of professor of violin and soloist of the Russian Musical Society. In September 1868 he left for Petersburg.

Russia unusually attracted Auer with the prospects of performing and teaching activities. She captivated his hot and energetic nature, and Auer, who originally intended to live here for only 3 years, renewed the contract again and again, becoming one of the most active builders of Russian musical culture. At the conservatory, he was a leading professor and a permanent member of the artistic council until 1917; taught solo violin and ensemble classes; from 1868 to 1906 he headed the Quartet of the St. Petersburg branch of the RMS, which was considered one of the best in Europe; annually gave dozens of solo concerts and chamber evenings. But the main thing is that he created a world-famous violin school, shining with such names as J. Heifetz, M. Polyakin, E. Zimbalist, M. Elman, A. Seidel, B. Sibor, L. Zeitlin, M. Bang, K. Parlow , M. and I. Piastro and many, many others.

Auer appeared in Russia during a period of fierce struggle that split the Russian musical community into two opposing camps. One of them was represented by the Mighty Handful headed by M. Balakirev, the other by the conservatives grouped around A. Rubinshtein.

Both directions played a big positive role in the development of Russian musical culture. The controversy between the “Kuchkists” and the “Conservatives” has been described many times and is well known. Naturally, Auer joined the “conservative” camp; he was in great friendship with A. Rubinstein, K. Davydov, P. Tchaikovsky. Auer called Rubinstein a genius and bowed before him; with Davydov, he was united not only by personal sympathies, but also by many years of joint activity in the RMS Quartet.

The Kuchkists at first treated Auer coldly. There are many critical remarks in the articles by Borodin and Cui on Auer’s speeches. Borodin accuses him of coldness, Cui – of impure intonation, ugly trill, colorlessness. But the Kuchkists spoke highly of Auer the Quartetist, considering him an infallible authority in this area.

When Rimsky-Korsakov became a professor at the conservatory, his attitude towards Auer generally changed little, remaining respectful but correctly cold. In turn, Auer had little sympathy for the Kuchkists and at the end of his life called them a “sect”, a “group of nationalists.”

A great friendship connected Auer with Tchaikovsky, and it shook only once, when the violinist could not appreciate the violin concerto dedicated to him by the composer.

It is no coincidence that Auer took such a high place in Russian musical culture. He possessed those qualities that were especially appreciated in the heyday of his performing activity, and therefore he was able to compete with such outstanding performers as Venyavsky and Laub, although he was inferior to them in terms of skill and talent. Auer’s contemporaries appreciated his artistic taste and subtle sense of classical music. In Auer’s playing, strictness and simplicity, the ability to get used to the performed work and convey its content in accordance with the character and style, were constantly noted. Auer was considered a very good interpreter of Bach’s sonatas, violin concerto and Beethoven’s quartets. His repertoire was also affected by the upbringing received from Joachim – from his teacher, he took a love for the music of Spohr, Viotti.

He often played the works of his contemporary, mainly German composers Raff, Molik, Bruch, Goldmark. However, if the performance of the Beethoven Concerto met with the most positive response from the Russian public, then the attraction to Spohr, Goldmark, Bruch, Raff caused a mostly negative reaction.

Virtuoso literature in Auer’s programs occupied a very modest place: from the legacy of Paganini, he played only “Moto perpetuo” in his youth, then some fantasies and Ernst’s Concerto, plays and concerts by Vietana, whom Auer greatly honored both as a performer and as a composer.

As the works of Russian composers appeared, he sought to enrich his repertoire with them; willingly played plays, concertos and ensembles by A. Rubinshtein. P. Tchaikovsky, C. Cui, and later – Glazunov.

They wrote about Auer’s playing that he does not have the strength and energy of Venyavsky, the phenomenal technique of Sarasate, “but he has no less valuable qualities: this is an extraordinary grace and roundness of tone, a sense of proportion and a highly meaningful musical phrasing and finishing the most subtle strokes. ; therefore, its execution meets the most stringent requirements.

“A serious and strict artist… gifted with the ability for brilliance and grace… that’s what Auer is,” they wrote about him back in the early 900s. And if in the 70s and 80s Auer was sometimes reproached for being too strict, bordering on coldness, then later it was noted that “over the years, it seems, he plays more cordially and more poetically, capturing the listener more and more deeply with his charming bow.”

Auer’s love for chamber music runs like a red thread through Auer’s entire life. During the years of his life in Russia, he played many times with A. Rubinstein; in the 80s, a great musical event was the performance of the entire cycle of Beethoven’s violin sonatas with the famous French pianist L. Brassin, who lived for some time in St. Petersburg. In the 90s, he repeated the same cycle with d’Albert. Auer’s sonata evenings with Raul Pugno attracted attention; Auer’s permanent ensemble with A. Esipova has delighted music connoisseurs for many years. About his work in the RMS Quartet, Auer wrote: “I immediately (on arrival in St. Petersburg. – L.R.) struck up a close friendship with Karl Davydov, the famous cellist, who was a few days older than me. On the occasion of our first quartet rehearsal, he took me into his house and introduced me to his charming wife. Over time, these rehearsals have become historic, as each new chamber piece for piano and strings has been invariably performed by our quartet, which performed it for the first time before the public. The second violin was played by Jacques Pickel, the first concertmaster of the Russian Imperial Opera Orchestra, and the viola part was played by Weikman, the first viola of the same orchestra. This ensemble played for the first time from a manuscript of Tchaikovsky’s early quartets. Arensky, Borodin, Cui and new compositions by Anton Rubinstein. Those were good days!”

However, Auer is not entirely accurate, since many of the Russian quartets were first played by other ensemble players, but, indeed, in St. Petersburg, most of the quartet compositions of Russian composers were originally performed by this ensemble.

Describing the activities of Auer, one cannot ignore his conducting. For several seasons he was the chief conductor of the symphony meetings of the RMS (1883, 1887-1892, 1894-1895), the organization of the symphony orchestra at the RMS is associated with his name. Usually the meetings were serviced by an opera orchestra. Unfortunately, the RMS orchestra, which arose only thanks to the energy of A. Rubinstein and Auer, lasted only 2 years (1881-1883) and was disbanded due to lack of funds. Auer as a conductor was well known and highly appreciated in Germany, Holland, France and other countries where he performed.

For 36 years (1872-1908) Auer worked at the Mariinsky Theater as an accompanist – soloist of the orchestra in ballet performances. Under him, the premieres of ballets by Tchaikovsky and Glazunov were held, he was the first interpreter of violin solos in their works.

This is the general picture of Auer’s musical activity in Russia.

There is little information about Auer’s personal life. Some living features in his biography are the memories of the amateur violinist A. V. Unkovskaya. She studied with Auer when she was still a girl. “Once a brunette with a small silky beard appeared in the house; this was the new violin teacher, Professor Auer. Grandma supervised. His dark brown, large, soft and intelligent eyes looked attentively at his grandmother, and, listening to her, he seemed to be analyzing her character; feeling this, my grandmother was apparently embarrassed, her old cheeks turned red, and I noticed that she was trying to speak as gracefully and smartly as possible – they spoke in French.

The inquisitiveness of a real psychologist, which Auer possessed, helped him in pedagogy.

On May 23, 1874, Auer married Nadezhda Evgenievna Pelikan, a relative of the then director of the Azanchevsky Conservatory, who came from a wealthy noble family. Nadezhda Evgenievna married Auer out of passionate love. Her father, Evgeny Ventseslavovich Pelikan, a well-known scientist, life physician, friend of Sechenov, Botkin, Eichwald, was a man of broad liberal views. However, despite his “liberalism”, he was very opposed to the marriage of his daughter with a “plebeian”, and in addition of Jewish origin. “For distraction,” writes R. Khin-Goldovskaya, “he sent his daughter to Moscow, but Moscow did not help, and Nadezhda Evgenievna turned from a well-born noblewoman into m-me Auer. The young couple made their honeymoon trip to Hungary, to some small place where mother “Poldi” … had a haberdashery shop. Mother Auer told everyone that Leopold had married a “Russian princess.” She adored her son so much that if he married the daughter of the emperor, she would not be surprised either. She treated her belle-soeur favorably and left her in the shop instead of herself when she went to rest.

Returning from abroad, the young Auers rented an excellent apartment and began to organize musical evenings, which on Tuesdays brought together local musical forces, St. Petersburg public figures and visiting celebrities.

Auer had four daughters from his marriage to Nadezhda Evgenievna: Zoya, Nadezhda, Natalya and Maria. Auer bought a magnificent villa in Dubbeln, where the family lived during the summer months. His house was distinguished by hospitality and hospitality, during the summer many guests came here. Khin-Goldovskaya spent one summer (1894) there, dedicating the following lines to Auer: “He himself is a magnificent musician, an amazing violinist, a person who has been very “polished” on European stages and in all circles of society … But … behind the external “polishedness” in all his manners one always feels a “plebeian” – a man from the people – smart, dexterous, cunning, rude and kind. If you take away the violin from him, then he can be an excellent stockbroker, commission agent, businessman, lawyer, doctor, whatever. He has beautiful black huge eyes, as if poured with oil. This “drag” disappears only when he plays great things … Beethoven, Bach. Then sparks of severe fire sparkle in them … At home, Khin-Goldovskaya continues, Auer is a sweet, affectionate, attentive husband, a kind, albeit strict father, who watches that the girls know “order.” He is very hospitable, pleasant, witty interlocutor; very intelligent, interested in politics, literature, art… Extraordinarily simple, not the slightest pose. Any student of the conservatory is more important than he, a European celebrity.

Auer had physically ungrateful hands and was forced to study for several hours a day, even in summer, during rest. He was exceptionally industrious. Work in the field of art was the basis of his life. “Study, work,” is his constant command to his students, the leitmotif of his letters to his daughters. He wrote about himself: “I am like a running machine, and nothing can stop me, except illness or death …”

Until 1883, Auer lived in Russia as an Austrian subject, then transferred to Russian citizenship. In 1896 he was granted the title of a hereditary nobleman, in 1903 – a state councilor, and in 1906 – a real state councilor.

Like most musicians of his time, he was far from politics and was rather calm about the negative aspects of Russian reality. He neither understood nor accepted the revolution of 1905, nor the February 1917 revolution, nor even the Great October Revolution. During the student unrest of 1905, which also seized the conservatory, he was on the side of the reactionary professors, but by the way, not out of political convictions, but because the unrest … was reflected in the classes. His conservatism was not fundamental. The violin provided him with a solid, solid position in society, he was busy with art all his life and went into it all, not thinking about the imperfection of the social system. Most of all, he was devoted to his students, they were his “works of art.” Taking care of his students became the need of his soul, and, of course, he left Russia, leaving his daughters, his family, the conservatory here, only because he ended up in America with his students.

In 1915-1917, Auer went on summer holidays to Norway, where he rested and worked at the same time, surrounded by his students. In 1917 he had to stay in Norway for the winter as well. Here he found the February revolution. At first, having received news of the revolutionary events, he simply wanted to wait them out in order to return to Russia, but he no longer had to do this. On February 7, 1918, he boarded a ship in Christiania with his students, and 10 days later the 73-year-old violinist arrived in New York. The presence in America of a large number of his St. Petersburg pupils provided Auer with a rapid influx of new students. He plunged into the work, which, as always, swallowed him whole.

The American period of Auer’s life did not bring brilliant pedagogical results to the remarkable violinist, but he was fruitful in that it was at this time that Auer, summing up his activities, wrote a number of books: Among Musicians, My School of Violin Playing, Violin Masterpieces and their interpretation”, “Progressive school of violin playing”, “Course of playing in an ensemble” in 4 notebooks. One can only be amazed at how much this man did at the turn of the seventh and eighth tens of his life!

Of the facts of a personal nature relating to the last period of his life, it is necessary to note his marriage to the pianist Wanda Bogutka Stein. Their romance began in Russia. Wanda left with Auer for the United States and, in accordance with American laws that do not recognize civil marriage, their union was formalized in 1924.

Until the end of his days, Auer retained remarkable vivacity, efficiency, and energy. His death came as a surprise to everyone. Every summer he traveled to Loschwitz, near Dresden. One evening, going out on the balcony in a light suit, he caught a cold and died of pneumonia a few days later. This happened on July 15, 1930.

Auer’s remains in a galvanized coffin were transported to the United States. The last funeral rite took place in the Orthodox Cathedral in New York. After the memorial service, Jascha Heifetz performed Schubert’s Ave, Maria, and I. Hoffmann performed part of Beethoven’s Moonlight Sonata. The coffin with the body of Auer was accompanied by a crowd of thousands of people, among whom were a lot of musicians.

The memory of Auer lives in the hearts of his students, who keep the great traditions of Russian realistic art of the XNUMXth century, which found deep expression in the performing and pedagogical work of their remarkable teacher.

L. Raaben