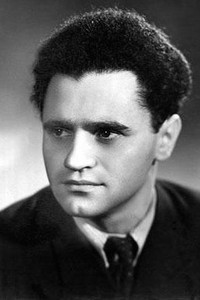

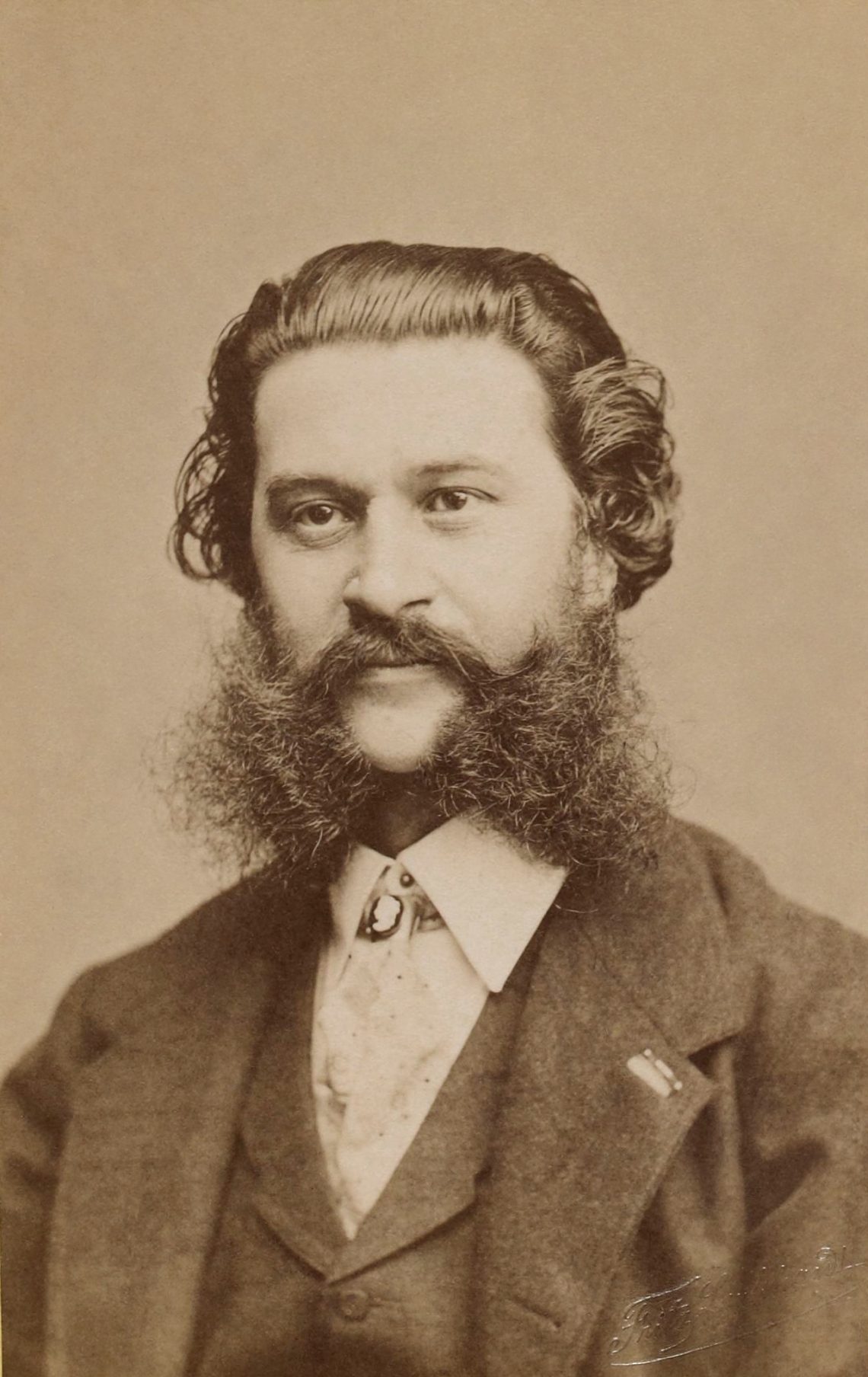

Johann Strauss (son) |

Johann Strauss (son)

The Austrian composer I. Strauss is called the “king of the waltz”. His work is thoroughly imbued with the spirit of Vienna with its long-standing tradition of love for dance. Inexhaustible inspiration combined with the highest skill made Strauss a true classic of dance music. Thanks to him, the Viennese waltz went beyond the XNUMXth century. and became part of today’s musical life.

Strauss was born into a family rich in musical traditions. His father, also Johann Strauss, organized his own orchestra in the year of his son’s birth and won fame throughout Europe with his waltzes, polkas, marches.

The father wanted to make his son a businessman and categorically objected to his musical education. All the more striking is the enormous talent of little Johann and his passionate desire for music. Secretly from his father, he takes violin lessons from F. Amon (accompanist of the Strauss orchestra) and at the age of 6 writes his first waltz. This was followed by a serious study of composition under the guidance of I. Drexler.

In 1844, nineteen-year-old Strauss gathers an orchestra from musicians of the same age and arranges his first dance evening. The young debutant became a dangerous rival to his father (who at that time was the conductor of the court ballroom orchestra). The intensive creative life of Strauss Jr. begins, gradually winning over the sympathies of the Viennese.

The composer appeared before the orchestra with a violin. He conducted and played at the same time (as in the days of I. Haydn and W. A. Mozart), and inspired the audience with his own performance.

Strauss used the form of the Viennese waltz that I. Lanner and his father developed: a “garland” of several, often five, melodic constructions with an introduction and conclusion. But the beauty and freshness of the melodies, their smoothness and lyricism, the Mozartian harmonious, transparent sound of the orchestra with spiritually singing violins, the overflowing joy of life – all this turns Strauss’s waltzes into romantic poems. Within the framework of applied, intended for dance music, masterpieces are created that deliver genuine aesthetic pleasure. The program names of Strauss waltzes reflected a wide variety of impressions and events. During the revolution of 1848, “Songs of Freedom”, “Songs of the Barricades” were created, in 1849 – “Waltz-obituary” on the death of his father. The hostile feeling towards his father (he started another family a long time ago) did not interfere with admiration for his music (later Strauss edited the complete collection of his works).

The fame of the composer is gradually growing and goes beyond the borders of Austria. In 1847 he tours in Serbia and Romania, in 1851 – in Germany, the Czech Republic and Poland, and then, for many years, regularly travels to Russia.

In 1856-65. Strauss participates in the summer seasons in Pavlovsk (near St. Petersburg), where he gives concerts in the station building and, along with his dance music, performs works by Russian composers: M. Glinka, P. Tchaikovsky, A. Serov. The waltz “Farewell to St. Petersburg”, the polka “In the Pavlovsk Forest”, the piano fantasy “In the Russian Village” (performed by A. Rubinshtein) and others are associated with impressions from Russia.

In 1863-70. Strauss is the conductor of court balls in Vienna. During these years, his best waltzes were created: “On the Beautiful Blue Danube”, “The Life of an Artist”, “Tales of the Vienna Woods”, “Enjoy Life”, etc. An unusual melodic gift (the composer said: “Melodies flow from me like water from crane”), as well as a rare ability to work allowed Strauss to write 168 waltzes, 117 polkas, 73 quadrilles, more than 30 mazurkas and gallops, 43 marches, and 15 operettas in his life.

70s – the beginning of a new stage in the creative life of Strauss, who, on the advice of J. Offenbach, turned to the genre of operetta. Together with F. Suppe and K. Millöcker, he became the creator of the Viennese classical operetta.

Strauss is not attracted by the satirical orientation of Offenbach’s theatre; as a rule, he writes cheerful musical comedies, the main (and often the only) charm of which is music.

Waltzes from the operettas Die Fledermaus (1874), Cagliostro in Vienna (1875), The Queen’s Lace Handkerchief (1880), Night in Venice (1883), Viennese Blood (1899) and others

Among Strauss’s operettas, The Gypsy Baron (1885) stands out with the most serious plot, conceived at first as an opera and absorbing some of its features (in particular, the lyric-romantic illumination of real, deep feelings: freedom, love, human dignity).

The music of the operetta makes extensive use of Hungarian-Gypsy motifs and genres, such as Čardas. At the end of his life, the composer writes his only comic opera The Knight Pasman (1892) and works on the ballet Cinderella (not finished). As before, although in smaller numbers, separate waltzes appear, full, as in their younger years, of genuine fun and sparkling cheerfulness: “Spring Voices” (1882). “Imperial Waltz” (1890). Tour trips also do not stop: to the USA (1872), as well as to Russia (1869, 1872, 1886).

Strauss’s music was admired by R. Schumann and G. Berlioz, F. Liszt and R. Wagner. G. Bulow and I. Brahms (former friend of the composer). For more than a century, she has conquered the hearts of people and does not lose her charm.

K. Zenkin

Johann Strauss entered the history of music of the XNUMXth century as a great master of dance and everyday music. He brought into it the features of genuine artistry, deepening and developing the typical features of the Austrian folk dance practice. The best works of Strauss are characterized by juiciness and simplicity of images, inexhaustible melodic richness, sincerity and naturalness of the musical language. All this contributed to their immense popularity among the broad masses of listeners.

Strauss wrote four hundred and seventy-seven waltzes, polkas, quadrilles, marches and other works of a concert and household plan (including transcriptions of excerpts from operettas). The reliance on rhythms and other means of expressiveness of folk dances gives these works a deeply national imprint. Contemporaries called Strauss waltzes patriotic songs without words. In musical images, he reflected the most sincere and attractive features of the character of the Austrian people, the beauty of his native landscape. At the same time, Strauss’s work absorbed the features of other national cultures, primarily Hungarian and Slavic music. This applies in many respects to the works created by Strauss for musical theater, including fifteen operettas, one comic opera and one ballet.

Major composers and performers – Strauss’s contemporaries highly appreciated his great talent and first-class skill as a composer and conductor. “Wonderful magician! His works (he himself conducted them) gave me a musical pleasure that I had not experienced for a long time,” Hans Bülow wrote about Strauss. And then he added: “This is a genius of conducting art in the conditions of its small genre. There is something to be learned from Strauss for the performance of the Ninth Symphony or Beethoven’s Pathétique Sonata.” Schumann’s words are also noteworthy: “Two things on earth are very difficult,” he said, “firstly, to achieve fame, and secondly, to keep it. Only true masters succeed: from Beethoven to Strauss – each in his own way. Berlioz, Liszt, Wagner, Brahms spoke enthusiastically about Strauss. With a feeling of deep sympathy Serov, Rimsky-Korsakov and Tchaikovsky spoke of him as a performer of Russian symphonic music. And in 1884, when Vienna solemnly celebrated the 40th anniversary of Strauss, A. Rubinstein, on behalf of the St. Petersburg artists, warmly welcomed the hero of the day.

Such a unanimous recognition of Strauss’s artistic merits by the most diverse representatives of the art of the XNUMXth century confirms the outstanding fame of this outstanding musician, whose best works still deliver high aesthetic pleasure.

* * *

Strauss is inextricably linked with the Viennese musical life, with the rise and development of the democratic traditions of Austrian music of the XNUMXth century, which clearly manifested themselves in the field of everyday dance.

Since the beginning of the century, small instrumental ensembles, the so-called “chapels”, have been popular in the Viennese suburbs, performing peasant landlers, Tyrolean or Styrian dances in taverns. The leaders of the chapels considered it a duty of honor to create new music of their own invention. When this music of the Viennese suburbs penetrated the great halls of the city, the names of its creators became known.

So the founders of the “waltz dynasty” came to glory Joseph Lanner (1801 — 1843) and Johann Strauss Senior (1804-1849). The first of them was the son of a glove-maker, the second was the son of an innkeeper; both from their youthful years played in instrumental choirs, and since 1825 they already had their own small string orchestra. Soon, however, Liner and Strauss diverge – friends become rivals. Everyone excels in creating a new repertoire for his orchestra.

Every year, the number of competitors increases more and more. And yet everyone is overshadowed by Strauss, who makes tours of Germany, France, and England with his orchestra. They are running with great success. But, finally, he also has an opponent, even more talented and strong. This is his son, Johann Strauss Jr., born October 25, 1825.

In 1844, nineteen-year-old I. Strauss, having recruited fifteen musicians, arranged his first dance evening. From now on, the struggle for superiority in Vienna begins between father and son, Strauss Jr. gradually conquered all those areas in which his father’s orchestra had previously ruled. The “duel” lasted intermittently for about five years and was cut short by the death of the forty-five-year-old Strauss Sr. (Despite the tense personal relationship, Strauss Jr. was proud of his father’s talent. In 1889, he published his dances in seven volumes (two hundred and fifty waltzes, gallops and quadrilles), where in the preface, among other things, he wrote: “Although to me, as a son , it is not proper to advertise a father, but I must say that it was thanks to him that Viennese dance music spread throughout the world.”)

By this time, that is, by the beginning of the 50s, the European popularity of his son had been consolidated.

Significant in this respect is Strauss’s invitation for the summer seasons to Pavlovsk, located in a picturesque area near St. Petersburg. For twelve seasons, from 1855 to 1865, and again in 1869 and 1872, he toured Russia with his brother Joseph, a talented composer and conductor. (Joseph Strauss (1827-1870) often wrote together with Johann; thus, the authorship of the famous Polka Pizzicato belongs to both of them. There was also a third brother – Edward, who also worked as a dance composer and conductor. In 1900, he dissolved the chapel, which, constantly renewing its composition, existed under the leadership of the Strauss for over seventy years.)

The concerts, which were given from May to September, were attended by many thousands of listeners and were accompanied by invariable success. Johann Strauss paid great attention to the works of Russian composers, he performed some of them for the first time (excerpts from Serov’s Judith in 1862, from Tchaikovsky’s Voyevoda in 1865); beginning in 1856, he often conducted Glinka’s compositions, and in 1864 he dedicated a special program to him. And in his work, Strauss reflected the Russian theme: folk tunes were used in the waltz “Farewell to Petersburg” (op. 210), “Russian Fantasy March” (op. 353), piano fantasy “In the Russian Village” (op. 355, her often performed by A. Rubinstein) and others. Johann Strauss always recalled with pleasure the years of his stay in Russia (The last time Strauss visited Russia was in 1886 and gave ten concerts in Petersburg.).

The next milestone of the triumphant tour and at the same time a turning point in his biography was a trip to America in 1872; Strauss gave fourteen concerts in Boston in a specially built building designed for a hundred thousand listeners. The performance was attended by twenty thousand musicians – singers and orchestra players and one hundred conductors – assistants to Strauss. Such “monster” concertos, born of unprincipled bourgeois entrepreneurship, did not provide the composer with artistic satisfaction. In the future, he refused such tours, although they could bring considerable income.

In general, since that time, Strauss’ concert trips have been sharply reduced. The number of dance and march pieces he created is also falling. (In the years 1844-1870, three hundred and forty-two dances and marches were written; in the years 1870-1899, one hundred and twenty plays of this kind, not counting adaptations, fantasies, and medleys on the themes of his operettas.)

The second period of creativity begins, mainly associated with the operetta genre. Strauss wrote his first musical and theatrical work in 1870. With tireless energy, but with varying success, he continued to work in this genre until his last days. Strauss died on June 3, 1899 at the age of seventy-four.

* * *

Johann Strauss devoted fifty-five years to creativity. He had a rare industriousness, composing incessantly, in any conditions. “Melodies flow from me like water from a tap,” he said jokingly. In the quantitatively huge legacy of Strauss, however, not everything is equal. Some of his writings bear traces of hasty, careless work. Sometimes the composer was led by the backward artistic tastes of his audience. But in general, he managed to solve one of the most difficult problems of our time.

In the years when low-grade salon musical literature, widely distributed by clever bourgeois businessmen, had a detrimental effect on the aesthetic education of the people, Strauss created truly artistic works, accessible and understandable to the masses. With the criterion of mastery inherent in “serious” art, he approached “light” music and therefore managed to erase the line that separated the “high” genre (concert, theatrical) from the supposedly “low” (domestic, entertaining). Other major composers of the past did the same, for example, Mozart, for whom there were no fundamental differences between “high” and “low” in art. But now there were other times – the onslaught of bourgeois vulgarity and philistinism needed to be countered with an artistically updated, light, entertaining genre.

This is what Strauss did.

M. Druskin

Short list of works:

Works of a concert-domestic plan waltzes, polkas, quadrilles, marches and others (total 477 pieces) The most famous are: “Perpetuum mobile” (“Perpetual motion”) op. 257 (1867) “Morning Leaf”, waltz op. 279 (1864) Lawyers’ Ball, polka op. 280 (1864) “Persian March” op. 289 (1864) “Blue Danube”, waltz op. 314 (1867) “The Life of an Artist”, waltz op. 316 (1867) “Tales of the Vienna Woods”, waltz op. 325 (1868) “Rejoice in life”, waltz op. 340 (1870) “1001 Nights”, waltz (from the operetta “Indigo and the 40 Thieves”) op. 346 (1871) “Viennese Blood”, waltz op. 354 (1872) “Tick-tock”, polka (from the operetta “Die Fledermaus”) op. 365 (1874) “You and You”, waltz (from the operetta “The Bat”) op. 367 (1874) “Beautiful May”, waltz (from the operetta “Methuselah”) op. 375 (1877) “Roses from the South”, waltz (from the operetta “The Queen’s Lace Handkerchief”) op. 388 (1880) “The Kissing Waltz” (from the operetta “Merry War”) op. 400 (1881) “Spring Voices”, waltz op. 410 (1882) “Favorite Waltz” (based on “The Gypsy Baron”) op. 418 (1885) “Imperial Waltz” op. 437 “Pizzicato Polka” (together with Josef Strauss) Operettas (total 15) The most famous are: The Bat, libretto by Meilhac and Halévy (1874) Night in Venice, libretto by Zell and Genet (1883) The Gypsy Baron, libretto by Schnitzer (1885) comic opera “Knight Pasman”, libretto by Dochi (1892) Ballet Cinderella (posthumously published)