Jean-Marie Leclair |

Jean Marie Leclair

One can still find sonatas by the outstanding French violinist of the first half of the XNUMXth century, Jean-Marie Leclerc, in the programs of concert violinists. Especially known is the C-minor one, which bears the subtitle “Remembrance”.

However, in order to understand its historical role, it is necessary to know the environment in which the violin art of France developed. Longer than in other countries, the violin was evaluated here as a plebeian instrument and the attitude towards it was dismissive. The viola reigned in the noble-aristocratic musical life. Its soft, muffled sound fully met the needs of the nobles playing music. The violin served national holidays, later – balls and masquerades in aristocratic houses, playing it was considered humiliating. Until the end of the 24th century, solo concert violin performance did not exist in France. True, in the XNUMXth century, several violinists who came out of the people and possessed remarkable skill gained fame. These are Jacques Cordier, nicknamed Bokan and Louis Constantin, but they did not perform as soloists. Bokan gave dance lessons at court, Constantin worked in the court ballroom ensemble, called “XNUMX Violins of the King.”

Violinists often acted as dance masters. In 1664, the violinist Dumanoir’s book The Marriage of Music and Dance appeared; the author of one of the violin schools of the first half of the 1718th century (published in XNUMX) Dupont calls himself a “teacher of music and dance.”

The fact that initially (since the end of the 1582th century) it was used in court music in the so-called “Stable Ensemble” testifies to the disdain for the violin. The ensemble (“chorus”) of the stable was called the chapel of wind instruments, which served the royal hunts, trips, picnics. In 24, the violin instruments were separated from the “Stable Ensemble” and the “Large Ensemble of Violinists” or otherwise “XNUMX Violins of the King” was formed from them to play at ballets, balls, masquerades and serve royal meals.

Ballet was of great importance in the development of French violin art. Lush and colorful court life, this kind of theatrical performances was especially close. It is characteristic that later danceability became almost a national stylistic feature of French violin music. Elegance, grace, plastic strokes, grace and elasticity of rhythms are the qualities inherent in French violin music. In court ballets, especially J.-B. Lully, the violin began to win the position of the solo instrument.

Not everyone knows that the greatest French composer of the 16th century, J.-B. Lully played the violin superbly. With his work, he contributed to the recognition of this instrument in France. He achieved the creation at the court of the “Small Ensemble” of violinists (out of 21, then 1866 musicians). By combining both ensembles, he received an impressive orchestra that accompanied the ceremonial ballets. But most importantly, the violin was entrusted with solo numbers in these ballets; in The Ballet of the Muses (XNUMX), Orpheus went on stage playing the violin. There is evidence that Lully personally played this role.

The level of skill of French violinists in the era of Lully can be judged by the fact that in his orchestra the performers owned the instrument only within the first position. An anecdote has been preserved that when a note was encountered in violin parts to on the fifth, which could be “reached” by stretching out the fourth finger without leaving the first position, it swept through the orchestra: “carefully – to!”

Even at the beginning of the 1712th century (in 1715), one of the French musicians, the theoretician and violinist Brossard, argued that in high positions the sound of the violin is forced and unpleasant; “in a word. it’s not a violin anymore.” In XNUMX, when Corelli’s trio sonatas reached France, none of the violinists could play them, since they did not own three positions. “The regent, the Duke of Orleans, a great lover of music, wanting to hear them, was forced to let three singers sing them … and only a few years later there were three violinists who could perform them.”

At the beginning of the 20th century, the violin art of France began to develop rapidly, and by the XNUMXs schools of violinists had already formed, forming two currents: the “French”, which inherited national traditions dating back to Lully, and the “Italian”, which was under the strong influence of Corelli. A fierce struggle flared up between them, a match for the future war of the buffoons, or the clashes of the “glukists” and “picchinists”. The French have always been expansive in their musical experiences; in addition, in this era the ideology of the encyclopedists began to mature, and passionate disputes were waged on every social, artistic, literary phenomenon.

F. Rebel (1666–1747) and J. Duval (1663–1728) belonged to the Lullist violinists, M. Maschiti (1664–1760) and J.-B. Senaye (1687-1730). The “French” trend developed special principles. It was characterized by dancing, gracefulness, short marked strokes. In contrast, violinists, influenced by Italian violin art, strove for melodiousness, a wide, rich cantilena.

How strong the differences between the two currents were can be judged by the fact that in 1725 the famous French harpsichordist Francois Couperin released a work called “The Apotheosis of Lully.” It “describes” (each number is provided with explanatory text) how Apollo offered Lully his place on Parnassus, how he meets Corelli there and Apollo convinces both that the perfection of music can only be achieved by combining French and Italian muses.

A group of the most talented violinists took the path of such an association, among which the brothers Francoeur Louis (1692-1745) and Francois (1693-1737) and Jean-Marie Leclerc (1697-1764) especially stood out.

The last of them can with good reason be considered the founder of the French classical violin school. In creativity and performance, he organically synthesized the most diverse currents of that time, paying the deepest tribute to the French national traditions, enriching them with those means of expression that were conquered by the Italian violin schools. Corelli – Vivaldi – Tartini. Leclerc’s biographer, the French scholar Lionel de la Laurencie, regards the years 1725-1750 as the time of the first flowering of the French violin culture, which by that time already had many brilliant violinists. Among them, he assigns the central place to Leclerc.

Leclerc was born in Lyon, in the family of a master craftsman (by profession a galloon). His father married the maiden Benoist-Ferrier on January 8, 1695, and had eight children from her – five boys and three girls. The eldest of this offspring was Jean-Marie. He was born on May 10, 1697.

According to ancient sources, the young Jean-Marie made his artistic debut at the age of 11 as a dancer in Rouen. In general, this was not surprising, since many violinists in France were engaged in dancing. However, without denying his activities in this area, Laurency expresses doubts whether Leclerc really went to Rouen. Most likely, he studied both arts in his native city, and even then, apparently, gradually, since he mainly expected to take up his father’s profession. Laurency proves that there was another dancer from Rouen who bore the name of Jean Leclerc.

In Lyon, on November 9, 1716, he married Marie-Rose Castagna, the daughter of a liquor seller. He was then a little over nineteen years old. Already at that time, he, obviously, was engaged not only in the craft of a galloon, but also mastered the profession of a musician, since from 1716 he was on the lists of those invited to the Lyon Opera. He probably received his initial violin education from his father, who introduced not only him, but all his sons to music. Jean-Marie’s brothers played in Lyon orchestras, and his father was listed as a cellist and dance teacher.

Jean-Marie’s wife had relatives in Italy, and perhaps through them Leclerc was invited in 1722 to Turin as the first dancer of the city ballet. But his stay in the Piedmontese capital was short-lived. A year later, he moved to Paris, where he published the first collection of sonatas for violin with digitized bass, dedicating it to Mr. Bonnier, the state treasurer of the province of Languedoc. Bonnier bought himself the title of Baron de Mosson for money, had his own hotel in Paris, two country residences – “Pas d’etrois” in Montpellier and the castle of Mosson. When the theater was closed in Turin, in connection with the death of the Princess of Piedmont. Leclerc lived for two months with this patron.

In 1726 he moved again to Turin. The Royal Orchestra in the city was led by the famous pupil of Corelli and the first-class violin teacher Somis. Leclerc began to take lessons from him, making amazing progress. As a result, already in 1728 he was able to perform in Paris with brilliant success.

During this period, the son of the recently deceased Bonnier begins to patronize him. He puts Leclerc in his hotel on St. Dominica. Leclerc dedicates to him the second collection of sonatas for solo violin with bass and 6 sonatas for 2 violins without bass (Op. 3), published in 1730. Leclerc often plays in the Spiritual Concerto, strengthening his fame as a soloist.

In 1733 he joined the court musicians, but not for long (until about 1737). The reason for his departure was a funny story that happened between him and his rival, the outstanding violinist Pierre Guignon. Each was so jealous of the glory of the other that he did not agree to play the second voice. Finally, they agreed to switch places every month. Guignon gave Leclair the beginning, but when the month was up and he had to change to second violin, he chose to leave the service.

In 1737, Leclerc traveled to Holland, where he met the greatest violinist of the first half of the XNUMXth century, a student of Corelli, Pietro Locatelli. This original and powerful composer had a great influence on Leclerc.

From Holland, Leclerc returned to Paris, where he remained until his death.

Numerous editions of works and frequent performances in concerts strengthened the well-being of the violinist. In 1758, he bought a two-story house with a garden on the Rue Carem-Prenant in the suburbs of Paris. The house was in a quiet corner of Paris. Leclerc lived in it alone, without servants and his wife, who most often visited friends in the city center. Leclerc’s stay in such a remote place worried his admirers. The Duke de Grammont repeatedly offered to live with him, while Leclerc preferred solitude. On October 23, 1764, early in the morning, a gardener, by the name of Bourgeois, passing near the house, noticed an ajar door. Almost simultaneously, Leclerc’s gardener, Jacques Peizan, approached and both noticed the musician’s hat and wig lying on the ground. Frightened, they called the neighbors and entered the house. Leclerc’s body lay in the vestibule. He was stabbed in the back. The killer and the motives of the crime remained unsolved.

Police records give a detailed description of the things left from Leclerc. Among them are an antique-style table trimmed with gold, several garden chairs, two dressing tables, an inlaid chest of drawers, another small chest of drawers, a favorite snuffbox, a spinet, two violins, etc. The most important value was the library. Leclerc was an educated and well-read man. His library consisted of 250 volumes and contained Ovid’s Metamorphoses, Milton’s Paradise Lost, works by Telemachus, Molière, Virgil.

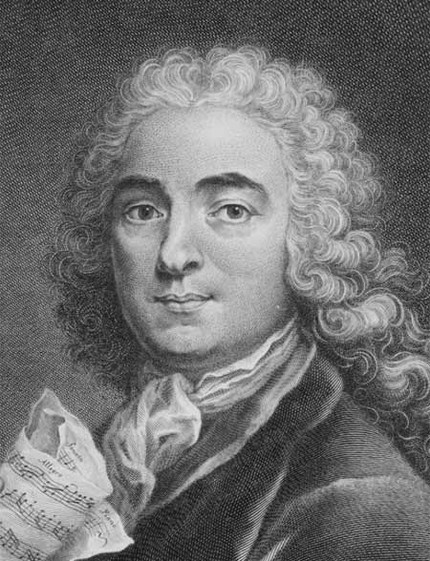

The only surviving portrait of Leclerc is by the painter Alexis Loire. It is kept in the print room of the National Library of Paris. Leclerc is depicted half-faced, holding a page of scribbled music paper in his hand. He has a full face, plump mouth and lively eyes. Contemporaries claim that he had a simple character, but was a proud and reflective person. Quoting one of the obituaries, Lorancey quotes the following words: “He was distinguished by the proud simplicity and bright character of a genius. He was serious and thoughtful and did not like the big world. Melancholic and lonely, he shunned his wife and preferred to live away from her and his children.

His fame was exceptional. About his works, poems were composed, enthusiastic reviews were written. Leclerc was considered a recognized master of the sonata genre, the creator of the French violin concerto.

His sonatas and concertos are extremely interesting in terms of style, a truly voracious fixation of the intonations characteristic of French, German and Italian violin music. In Leclerc, some parts of the concertos sound quite “Bachian”, although on the whole he is far from a polyphonic style; a lot of intonation turns are found, borrowed from Corelli, Vivaldi, and in the pathetic “arias” and in the sparkling final rondos he is a true Frenchman; No wonder contemporaries so appreciated his work precisely for its national character. From national traditions comes the “portrait”, the depiction of individual parts of the sonatas, in which they resemble Couperin’s harpsichord miniatures. Synthesizing these very different elements of melos, he fuses them in such a way that he achieves an exceptional monolithic style.

Leclerc wrote only violin works (with the exception of the opera Scylla and Glaucus, 1746) – sonatas for violin with bass (48), trio sonatas, concertos (12), sonatas for two violins without bass, etc.

As a violinist, Leclerc was a perfect master of the then technique of playing and was especially famous for the performance of chords, double notes, and the absolute purity of intonation. One of Leclerc’s friends and a fine connoisseur of music, Rosois, calls him “a profound genius who turns the very mechanics of the game into art.” Very often, the word “scientist” is used in relation to Leclerc, which testifies to the well-known intellectualism of his performance and creativity and makes one think that much in his art brought him closer to the encyclopedists and outlined the path to classicism. “His game was wise, but there was no hesitation in this wisdom; it was the result of exceptional taste, and not from lack of courage or freedom.

Here is the review of another contemporary: “Leclerc was the first to connect the pleasant with the useful in his works; he is a very learned composer and plays double notes with a perfection that is hard to beat. He has a happy connection of the bow with the fingers (left hand. – L. R.) and plays with exceptional purity: and if, perhaps, he is sometimes reproached for having a certain coldness in his manner of transmission, then this comes from a lack of temperament, who is usually the absolute master of almost all people.” Citing these reviews, Lorancey highlights the following qualities of Leclerc’s playing: “Deliberate courage, incomparable virtuosity, combined with perfect correction; maybe some dryness with a certain clarity and clarity. In addition – majesty, firmness and restrained tenderness.

Leclerc was an excellent teacher. Among his students are the most famous violinists of France – L’Abbe-son, Dovergne and Burton.

Leclerc, along with Gavinier and Viotti, made the glory of the French violin art of the XNUMXth century.

L. Raaben