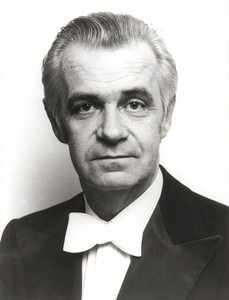

Jascha Heifetz |

Jascha Heifetz

Writing a biographical sketch of Heifetz is infinitely difficult. It seems that he has not yet told anyone in detail about his life. He is named the most secretive person in the world in the article by Nicole Hirsch “Jascha Heifetz – Emperor of the Violin”, which is one of the few containing interesting information about his life, personality and character.

He seemed to fence himself off from the world around him with a proud wall of alienation, allowing only a few, the chosen ones, to look into it. “He hates crowds, noise, dinners after the concert. He even once refused the invitation of the King of Denmark, informing His Majesty with all due respect that he was not going anywhere after he played.

Yasha, or rather Iosif Kheyfets (the diminutive name Yasha was called in childhood, then it turned into a kind of artistic pseudonym) was born in Vilna on February 2, 1901. The present-day handsome Vilnius, the capital of Soviet Lithuania, was a remote city inhabited by the Jewish poor, engaged in all conceivable and inconceivable crafts – the poor, so colorfully described by Sholom Aleichem.

Yasha’s father Reuben Heifetz was a klezmer, a violinist who played at weddings. When it was especially difficult, he, along with his brother Nathan, walked around the yards, squeezing out a penny for food.

Everyone who knew Heifetz’s father claims that he was musically gifted no less than his son, and only hopeless poverty in his youth, the absolute impossibility of getting a musical education, prevented his talent from developing.

Which of the Jews, especially musicians, did not dream of making his son “a violinist for the whole world”? So Yasha’s father, when the child was only 3 years old, already bought him a violin and began to teach him on this instrument himself. However, the boy made such rapid progress that his father hurried to send him to study with the famous Vilna violinist teacher Ilya Malkin. At the age of 6, Yasha gave his first concert in his native city, after which it was decided to take him to St. Petersburg to the famous Auer.

The laws of the Russian Empire forbade Jews to live in St. Petersburg. This required special permission from the police. However, the director of the conservatory A. Glazunov, by the power of his authority, usually sought such permission for his gifted pupils, for which he was even jokingly nicknamed “the king of the Jews.”

In order for Yasha to live with his parents, Glazunov accepted Yasha’s father as a student at the conservatory. That is why the lists of the Auer class from 1911 to 1916 include two Heifetz – Joseph and Reuben.

At first, Yasha studied for some time with Auer’s adjunct, I. Nalbandyan, who, as a rule, did all the preparatory work with the students of the famous professor, adjusting their technical apparatus. Auer then took the boy under his wing, and soon Heifetz became the first star among the bright constellation of students at the conservatory.

Heifetz’s brilliant debut, which immediately brought him almost international fame, was a performance in Berlin on the eve of the First World War. The 13-year-old boy was accompanied by Artur Nikish. Kreisler, who was present at the concert, heard him play and exclaimed: “With what pleasure I would break my violin now!”

Auer liked to spend the summer with his students in the picturesque town of Loschwitz, located on the banks of the Elbe, near Dresden. In his book Among the Musicians, he mentions a Loschwitz concert in which Heifetz and Seidel performed Bach’s Concerto for two violins in D minor. Musicians from Dresden and Berlin came to listen to this concert: “The guests were deeply touched by the purity and unity of style, deep sincerity, not to mention the technical perfection with which both boys in sailor blouses, Jascha Heifetz and Toscha Seidel, played this beautiful work.”

In the same book, Auer describes how the outbreak of war found him with his students in Loschwitz, and the Heifets family in Berlin. Auer was kept under the strictest police supervision until October, and Kheyfetsov until December 1914. In December, Yasha Kheyfets and his father reappeared in Petrograd and were able to start studying.

Auer spent the summer months of 1915-1917 in Norway, in the vicinity of Christiania. In the summer of 1916 he was accompanied by the Heifetz and Seidel families. “Tosha Seidel was returning to a country where he was already known. The name of Yasha Heifetz was completely unfamiliar to the general public. However, his impresario found in the library of one of the largest Christiania newspapers a Berlin article for 1914, which gave an enthusiastic review of Heifetz’s sensational performance at a symphony concert in Berlin conducted by Arthur Nikisch. As a result, tickets for Heifetz’s concerts were sold out. Seidel and Heifetz were invited by the Norwegian king and performed in his palace the Bach Concerto, which in 1914 was admired by Loschwitz’s guests. These were the first steps of Heifetz in the artistic field.

In the summer of 1917, he signed a contract for a trip to the United States and through Siberia to Japan, he moved with his family to California. It is unlikely that he imagined then that America would become his second home and he would have to come to Russia only once, already a mature person, as a guest performer.

They say that the first concert in New York’s Carnegie Hall attracted a large group of musicians – pianists, violinists. The concert was a phenomenal success and immediately made the name of Heifetz famous in the musical circles of America. “He played like a god the entire virtuoso violin repertoire, and Paganini’s touches never seemed so diabolical. Misha Elman was in the hall with pianist Godovsky. He leaned towards him, “Don’t you find it’s very hot in here?” And in response: “Not at all for a pianist.”

In America, and throughout the Western world, Jascha Heifetz took first place among violinists. His fame is enchanting, legendary. “According to Heifetz” they evaluate the rest, even very large performers, neglecting stylistic and individual differences. “The greatest violinists of the world recognize him as their master, as their model. Although the music at the moment is by no means poor with very large violinists, but as soon as you see Jascha Heifets appearing on the stage, you immediately understand that he really rises above everyone else. In addition, you always feel it somewhat in the distance; he does not smile in the hall; he barely looks there. He holds his violin – a 1742 Guarneri once owned by Sarasata – with tenderness. He is known to leave it in the case until the very last moment and never act out before going on stage. He holds himself like a prince and reigns on the stage. The hall freezes, holding its breath, admiring this man.

Indeed, those who attended Heifetz’s concerts will never forget his royally proud appearances, imperious posture, unconstrained freedom while playing with a minimum of movements, and even more so will remember the captivating power of the impact of his remarkable art.

In 1925, Heifetz received American citizenship. In the 30s he was the idol of the American musical community. His game is recorded by the largest gramophone companies; he acts in films as an artist, a film is made about him.

In 1934, he visited the Soviet Union for the only time. He was invited to our tour by the People’s Commissar for Foreign Affairs M. M. Litvinov. On the way to the USSR, Kheifets passed through Berlin. Germany quickly slipped into fascism, but the capital still wanted to listen to the famous violinist. Heifets was greeted with flowers, Goebbels expressed a desire that the famous artist honor Berlin with his presence and give several concerts. However, the violinist flatly refused.

His concerts in Moscow and Leningrad gather an enthusiastic audience. Yes, and no wonder – the art of Heifetz by the mid-30s had reached full maturity. Responding to his concerts, I. Yampolsky writes about “full-blooded musicality”, “classical precision of expression.” “Art is of great scope and great potential. It combines monumental austerity and virtuoso brilliance, plastic expressiveness and chasing form. Whether he’s playing a small trinket or a Brahms Concerto, he equally delivers them close-up. He is equally alien to affectation and triviality, sentimentality and mannerisms. In his Andante from Mendelssohn’s Concerto there is no “Mendelssohnism”, and in Canzonetta from Tchaikovsky’s Concerto there is no elegiac anguish of “chanson triste”, common in the interpretation of violinists … ”Noting the restraint in Heifetz’s playing, he rightly points out that this restraint in no way means coldness .

In Moscow and Leningrad, Kheifets met with his old comrades in Auer’s class – Miron Polyakin, Lev Tseytlin, and others; he also met with Nalbandyan, the first teacher who had once prepared him for the Auer class at the St. Petersburg Conservatory. Remembering the past, he walked along the corridors of the conservatory that raised him, stood for a long time in the classroom, where he once came to his stern and demanding professor.

There is no way to trace the life of Heifetz in chronological order, it is too hidden from prying eyes. But according to the mean columns of newspaper and magazine articles, according to the testimonies of people who personally met him, one can get some idea of uXNUMXbuXNUMXbhis way of life, personality and character.

“At first glance,” writes K. Flesh, “Kheifetz gives the impression of a phlegmatic person. The features of his face seem motionless, harsh; but this is just a mask behind which he hides his true feelings .. He has a subtle sense of humor, which you do not suspect when you first meet him. Heifetz hilariously imitates the game of mediocre students.

Similar features are also noted by Nicole Hirsch. She also writes that Heifetz’s coldness and arrogance are purely external: in fact, he is modest, even shy, and kind at heart. In Paris, for example, he willingly gave concerts for the benefit of elderly musicians. Hirsch also mentions that he is very fond of humor, jokes and is not averse to throwing out some funny number with his loved ones. On this occasion, she cites a funny story with the impresario Maurice Dandelo. Once, before the start of the concert, Kheifets called Dandelo, who was in control, to his artistic room and asked him to immediately pay him a fee even before the performance.

“But an artist is never paid before a concert.

– I insist.

— Ah! Leave me alone!

With these words, Dandelo throws an envelope with money on the table and goes to the control. After some time, he returns to warn Heifetz about entering the stage and … finds the room empty. No footman, no violin case, no Japanese maid, no one. Just an envelope on the table. Dandelo sits down at the table and reads: “Maurice, never pay an artist before a concert. We all went to the cinema.”

One can imagine the state of the impresario. In fact, the whole company hid in the room and watched Dandelo with pleasure. They could not stand this comedy for a long time and burst into loud laughter. However, Hirsch adds, Dandelo will probably never forget the trickle of cold sweat that ran down his neck that evening until the end of his days.

In general, her article contains many interesting details about the personality of Heifetz, his tastes and family environment. Hirsch writes that if he refuses invitations to dinners after concerts, it is only because he likes, inviting two or three friends to his hotel, to personally cut the chicken he cooked himself. “He opens a bottle of champagne, changes stage clothes to home. The artist feels then a happy person.

While in Paris, he looks into all the antique shops, and also arranges good dinners for himself. “He knows the addresses of all the bistros and the recipe for American-style lobsters, which he eats mostly with his fingers, with a napkin around his neck, forgetting about fame and music…” Getting into a particular country, he certainly visits its attractions, museums; He is fluent in several European languages - French (up to local dialects and common jargon), English, German. Brilliantly knows literature, poetry; madly in love, for example, with Pushkin, whose poems he quotes by heart. However, there are oddities in his literary tastes. According to his sister, S. Heifetz, he treats the work of Romain Rolland very coolly, disliking him for “Jean Christophe”.

In music, Heifetz prefers the classical; the works of modern composers, especially those of the “left,” rarely satisfy him. At the same time, he is fond of jazz, though certain types of it, since rock and roll types of jazz music terrify him. “One evening I went to the local club to listen to a famous comic artist. Suddenly, the sound of rock and roll was heard. I felt like I was losing consciousness. Rather, he pulled out a handkerchief, tore it into pieces and plugged his ears … “.

Heifetz’s first wife was the famous American film actress Florence Vidor. Before him, she was married to a brilliant film director. From Florence, Heifetz left two children – a son and a daughter. He taught both of them to play the violin. The daughter mastered this instrument more thoroughly than the son. She often accompanies her father on his tours. As for the son, the violin interests him to a very small extent, and he prefers to engage not in music, but in collecting postage stamps, competing in this with his father. Currently, Jascha Heifetz has one of the richest vintage collections in the world.

Heifetz lives almost constantly in California, where he has his own villa in the picturesque Los Angeles suburb of Beverly Hill, near Hollywood.

The villa has excellent grounds for all kinds of games – a tennis court, ping-pong tables, whose invincible champion is the owner of the house. Heifetz is an excellent athlete – he swims, drives a car, plays tennis superbly. Therefore, probably, he still, although he is already over 60 years old, amazes with vivacity and strength of the body. A few years ago, an unpleasant incident happened to him – he broke his hip and was out of order for 6 months. However, his iron body helped to safely get out of this story.

Heifetz is a hard worker. He still plays the violin a lot, although he works carefully. In general, both in life and in work, he is very organized. Organization, thoughtfulness are also reflected in his performance, which always strikes with the sculptural chasing of the form.

He loves chamber music and often plays music at home with cellist Grigory Pyatigorsky or violist William Primrose, as well as Arthur Rubinstein. “Sometimes they give ‘luxe sessions’ to select audiences of 200-300 people.”

In recent years, Kheifets has given concerts very rarely. So, in 1962, he gave only 6 concerts – 4 in the USA, 1 in London and 1 in Paris. He is very rich and the material side does not interest him. Nickel Hirsch reports that only on the money received from 160 discs of records made by him during his artistic life, he will be able to live until the end of his days. The biographer adds that in past years, Kheifetz rarely performed – no more than twice a week.

Heifetz’s musical interests are very wide: he is not only a violinist, but also an excellent conductor, and besides, a gifted composer. He has many first-class concert transcriptions and a number of his own original works for violin.

In 1959, Heifetz was invited to take a professorship in violin at the University of California. He accepted 5 students and 8 as listeners. One of his students, Beverly Somah, says that Heifetz comes to class with a violin and demonstrates performance techniques along the way: “These demonstrations represent the most amazing violin playing that I have ever heard.”

The note reports that Heifetz insists that students should work daily on scales, play Bach’s sonatas, Kreutzer’s etudes (which he always plays himself, calling them “my bible”) and Carl Flesch’s Basic Etudes for Violin Without a Bow. If something is not going well with the student, Heifetz recommends working slowly on this part. In parting words to his students, he says: “Be your own critics. Never rest on your laurels, never give yourself discounts. If something doesn’t work out for you, don’t blame the violin, strings, etc. Tell yourself it’s my fault, and try to find the cause of your shortcomings yourself … ”

The words that complete his thought seem ordinary. But if you think about it, then from them you can draw a conclusion about some features of the pedagogical method of the great artist. Scales… how often violin learners do not attach importance to them, and how much use one can derive from them in mastering controlled finger technique! How faithful Heifetz also remained to the classical school of Auer, relying so far on Kreutzer’s etudes! And, finally, what importance he attaches to the student’s independent work, his ability for introspection, critical attitude towards himself, what a harsh principle behind all this!

According to Hirsch, Kheifets accepted not 5, but 6 students into his class, and he settled them at home. “Every day they meet with the master and use his advice. One of his students, Eric Friedman, made his successful debut in London. In 1962 he gave concerts in Paris”; in 1966 he received the title of laureate of the International Tchaikovsky Competition in Moscow.

Finally, information about Heifetz’s pedagogy, somewhat different from the above, is found in an article by an American journalist from “Saturday Evening”, reprinted by the magazine “Musical Life”: “It’s nice to sit with Heifetz in his new studio overlooking Beverly Hills. The musician’s hair has turned gray, he has become a little stout, traces of the past years are visible on his face, but his bright eyes still shine. He loves to talk, and speaks enthusiastically and sincerely. On the stage, Kheifets seems cold and reserved, but at home he is a different person. His laughter sounds warm and cordial, and he gestures expressively when he speaks.”

With his class, Kheifetz works out 2 times a week, not every day. And again, and in this article, it is about the scales that he requires to play on acceptance tests. “Heifetz considers them the foundation of excellence.” “He is very demanding and, having accepted five students in 1960, he refused two before the summer holidays.

“Now I only have two students,” he remarked, laughing. “I’m afraid that in the end I will come someday to an empty auditorium, sit alone for a while and go home. – And he added already seriously: This is not a factory, mass production cannot be established here. Most of my students didn’t have the necessary training.”

“We are in dire need of performing teachers,” Kheyfets continues. “No one plays by himself, everyone is limited to oral explanations … ”According to Heifets, it is necessary that the teacher plays well and can show the student this or that work. “And no amount of theoretical reasoning can replace that.” He ends his presentation of his thoughts on pedagogy with the words: “There are no magic words that can reveal the secrets of violin art. There is no button, which would be enough to press to play correctly. You have to work hard, then only your violin will sound.

How all this resonates with Auer’s pedagogical attitudes!

Considering the performing style of Heifetz, Carl Flesh sees some extreme poles in his playing. In his opinion, Kheifets sometimes plays “with one hand”, without the participation of creative emotions. “However, when inspiration comes to him, the greatest artist-artist awakens. Such examples include his interpretation of the Sibelius Concerto, unusual in its artistic colors; She’s on tape. In those cases when Heifetz plays without inner enthusiasm, his game, mercilessly cold, can be likened to an amazingly beautiful marble statue. As a violinist, he is invariably ready for anything, but, as an artist, he is not always inwardly .. “

Flesh is right in pointing out the poles of Heifetz’s performance, but, in our opinion, he is absolutely wrong in explaining their essence. And can a musician of such richness even play “with one hand”? It’s just impossible! The point, of course, is something else – in the very individuality of Heifets, in his understanding of various phenomena of music, in his approach to them. In Heifetz, as an artist, it is as if two principles are opposed, closely interacting and synthesizing with each other, but in such a way that in some cases one dominates, in others the other. These beginnings are sublimely “classic” and expressive and dramatic. It is no coincidence that Flash compares the “mercilessly cold” sphere of Heifetz’s game with an amazingly beautiful marble statue. In such a comparison, there is a recognition of high perfection, and it would be unattainable if Kheifets played “with one hand” and, as an artist, would not be “ready” for performance.

In one of his articles, the author of this work defined Heifetz’s performing style as the style of modern “high classicism”. It seems to us that this is much more in line with the truth. In fact, the classical style is usually understood as sublime and at the same time strict art, pathetic and at the same time severe, and most importantly – controlled by the intellect. Classicism is an intellectualized style. But after all, everything that has been said is highly applicable to Heifets, in any case, to one of the “poles” of his performing art. Let us recall again about organization as a distinctive feature of Heifetz’s nature, which also manifests itself in his performance. Such a normative nature of musical thinking is a feature characteristic of a classicist, and not of a romantic.

We called the other “pole” of his art “expressive-dramatic”, and Flesh pointed to a really brilliant example of it – the recording of the Sibelius Concerto. Here everything boils, boils in a passionate outpouring of emotions; there is not a single “indifferent”, “empty” note. However, the fire of passions has a severe connotation – this is the fire of Prometheus.

Another example of Heifetz’s dramatic style is his performance of the Brahms Concerto, extremely dynamized, saturated with truly volcanic energy. It is characteristic that in it Heifets emphasizes not the romantic, but the classical beginning.

It is often said of Heifetz that he retains the principles of the Auerian school. However, what exactly and which ones are usually not indicated. Some elements of his repertoire remind of them. Heifetz continues to perform works that were once studied in the class of Auer and have almost already left the repertoire of major concert players of our era – the Bruch concertos, the Fourth Vietana, Ernst’s Hungarian Melodies, etc.

But, of course, not only this connects the student with the teacher. The Auer school developed on the basis of the high traditions of instrumental art of the XNUMXth century, which was characterized by melodious “vocal” instrumentalism. A full-blooded, rich cantilena, a kind of proud bel canto, also distinguishes Heifetz’s playing, especially when he sings Schubert’s “Ave, Marie”. However, the “vocalization” of Heifetz’s instrumental speech consists not only in its “belcanto”, but much more in a hot, declamatory intonation, reminiscent of the singer’s passionate monologues. And in this respect, he is, perhaps, no longer the heir of Auer, but rather of Chaliapin. When you listen to the Sibelius Concerto performed by Heifets, often his manner of intonation of phrases, as if uttered by a “squeezed” throat from experience and on characteristic “breathing”, “entrances”, resembles Chaliapin’s recitation.

Relying on the traditions of Auer-Chaliapin, Kheifets, at the same time, modernizes them extremely. The art of the 1934th century was not familiar with the dynamism inherent in the game of Heifetz. Let us point again to the Brahms Concerto played by Heifets in an “iron”, truly ostinato rhythm. Let us also recall the revealing lines of Yampolsky’s review (XNUMX), where he writes about the absence of “Mendelssohnism” in Mendelssohn’s Concerto and elegiac anguish in the Canzonette from Tchaikovsky’s Concerto. From the game of Heifetz, therefore, what was very typical of the performance of the XNUMXth century disappears – sentimentalism, sensitive affectation, romantic elegiacism. And this despite the fact that Heifetz often uses glissando, a tart portamento. But they, combined with a sharp accent, acquire a courageously dramatic sound, very different from the sensitive gliding of the violinists of the XNUMXth and early XNUMXth centuries.

One artist, no matter how wide and multifaceted, will never be able to reflect all the aesthetic trends of the era in which he lives. And yet, when you think about Heifetz, you involuntarily have the idea that it was in him, in all his appearance, in all his unique art, that very important, very significant and very revealing features of our modernity were embodied.

L. Raaben, 1967