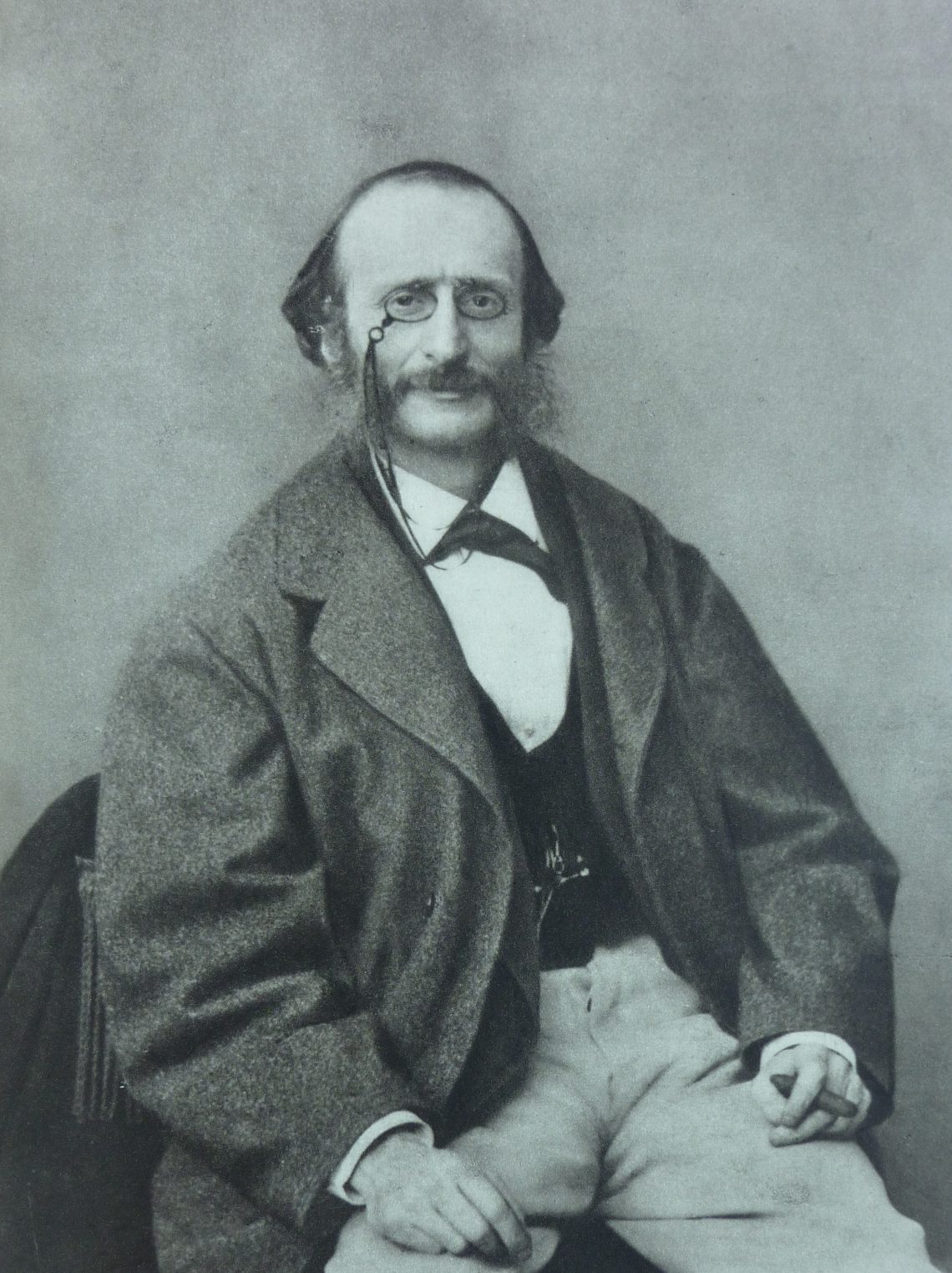

Jacques Offenbach |

Jacques Offenbach

“Offenbach was—no matter how loud it sounds—one of the most gifted composers of the 6th century,” wrote I. Sollertinsky. “Only he worked in a completely different genre than Schumann or Mendelssohn, Wagner or Brahms. He was a brilliant musical feuilletonist, buff satirist, improviser…” He created 100 operas, a number of romances and vocal ensembles, but the main genre of his work is operetta (about XNUMX). Among Offenbach’s operettas, Orpheus in Hell, La Belle Helena, Life in Paris, The Duchess of Gerolstein, Pericola, and others stand out in their significance. into an operetta of social witticism, often turning it into a parody of the life of the contemporary Second Empire, denouncing the cynicism and depravity of society, “feverishly dancing on a volcano”, at the moment of an uncontrollably rapid movement towards the Sedan catastrophe. “… Thanks to the universal satirical scope, the breadth of grotesque and accusatory generalizations,” I. Sollertinsky noted, “Offenbach leaves the ranks of operetta composers — Herve, Lecoq, Johann Strauss, Lehar — and approaches the phalanx of great satirists — Aristophanes, Rabelais, Swift , Voltaire, Daumier, etc. Offenbach’s music, inexhaustible in melodic generosity and rhythmic ingenuity, marked by great individual originality, relies primarily on French urban folklore, the practice of Parisian chansonniers, and dances popular at that time, especially gallop and quadrille. She absorbed wonderful artistic traditions: the wit and brilliance of G. Rossini, the fiery temperament of K. M. Weber, the lyricism of A. Boildieu and F. Herold, the piquant rhythms of F. Aubert. The composer directly developed the achievements of his compatriot and contemporary – one of the creators of the French classical operetta F. Hervé. But most of all, in terms of lightness and grace, Offenbach echoes W. A. Mozart; it was not without reason that he was called the “Mozart of the Champs Elysees”.

J. Offenbach was born into the family of a synagogue cantor. Possessing exceptional musical abilities, by the age of 7 he mastered the violin with the help of his father, by the age of 10 he independently learned to play the cello, and by the age of 12 he began to perform in concerts as a virtuoso cellist and composer. In 1833, having moved to Paris – the city that became his second home, where he lived almost all his life – the young musician entered the conservatory in the class of F. Halevi. In the first years after graduating from the conservatory, he worked as a cellist in the orchestra of the Opera Comique theatre, performed in entertainment establishments and salons, and wrote theater and pop music. Vigorously giving concerts in Paris, he also toured for a long time in London (1844) and Cologne (1840 and 1843), where in one of the concerts F. Liszt accompanied him in recognition of the talent of the young performer. From 1850 to 1855 Offenbach worked as a staff composer and conductor at the Theater Francais, composing music for the tragedies of P. Corneille and J. Racine.

In 1855, Offenbach opened his own theater, Bouffes Parisiens, where he worked not only as a composer, but also as an entrepreneur, stage director, conductor, co-author of librettists. Like his contemporaries, the famous French cartoonists O. Daumier and P. Gavarni, the comedian E. Labiche, Offenbach saturates his performances with subtle and caustic wit, and sometimes with sarcasm. The composer attracted congenial writers-librettists A. Melyak and L. Halevi, the true co-authors of his performances. And a small, modest theater on the Champs Elysees is gradually becoming a favorite meeting place for the Parisian public. The first grandiose success was won by the operetta “Orpheus in Hell”, staged in 1858 and withstood 288 performances in a row. This biting parody of academic antiquity, in which the gods descend from Mount Olympus and dance a frenzied cancan, contained a clear allusion to the structure of modern society and modern mores. Further musical and stage works – no matter what subject they are written on (antiquity and images of popular fairy tales, the Middle Ages and Peruvian exoticism, the events of French history of the XNUMXth century and the life of contemporaries) – invariably reflect modern mores in a parodic, comic or lyrical key.

Following “Orpheus” are put “Genevieve of Brabant” (1859), “Fortunio’s Song” (1861), “Beautiful Elena” (1864), “Bluebeard” (1866), “Paris Life” (1866), “Duchess of Gerolstein” (1867), “Perichole” (1868), “Robbers” (1869). Offenbach’s fame spreads outside of France. His operettas are staged abroad, especially often in Vienna and St. Petersburg. In 1861, he removed himself from the leadership of the theater in order to be able to constantly go on tour. The zenith of his fame is the Paris World Exhibition of 1867, where “Parisian Life” is performed, which brought together the kings of Portugal, Sweden, Norway, the Viceroy of Egypt, the Prince of Wales and the Russian Tsar Alexander II in the stalls of the Bouffes Parisiens theater. The Franco-Prussian War interrupted Offenbach’s brilliant career. His operettas leave the stage. In 1875, he was forced to declare himself bankrupt. In 1876, in order to financially support his family, he went on tour to the United States, where he conducted garden concerts. In the year of the Second World Exhibition (1878), Offenbach is almost forgotten. The success of his two later operettas Madame Favard (1878) and The Daughter of Tambour Major (1879) somewhat brightens up the situation, but Offenbach’s glory is finally overshadowed by the operettas of the young French composer Ch. Lecoq. Struck by a heart disease, Offenbach is working on a work that he considers his life’s work – the lyric-comic opera The Tales of Hoffmann. It reflects the romantic theme of the unattainability of the ideal, the illusory nature of earthly existence. But the composer did not live to see its premiere; it was completed and staged by E. Guiraud in 1881.

I. Nemirovskaya

Just as Meyerbeer assumed the leading position in the musical life of Paris during the period of the bourgeois monarchy of Louis Philippe, so Offenbach achieved the widest recognition during the Second Empire. In the work and in the very individual appearance of both major artists, the essential features of reality were reflected; they became the mouthpieces of their time, both its positive and negative aspects. And if Meyerbeer is rightfully considered the creator of the genre of French “grand” opera, then Offenbach is a classic of French, or rather, Parisian operetta.

What are its characteristic features?

The Parisian operetta is a product of the Second Empire. This is a mirror of her social life, which often gave a frank image of modern ulcers and vices. The operetta grew out of theatrical interludes or revue-type reviews that responded to the topical issues of the day. The practice of artistic gatherings, brilliant and witty improvisations of goguettes, as well as the tradition of chansonniers, these talented masters of urban folklore, poured a life-giving stream into these performances. What the comic opera failed to do, that is, to saturate the performance with modern content and the modern system of musical intonations, was done by the operetta.

It would be wrong, however, to overestimate its socially revealing significance. Careless in character, mocking in tone and frivolous in content – this was the main features of this cheerful theatrical genre. The authors of operetta performances used anecdotal plots, often gleaned from tabloid newspaper chronicles, and strove, first of all, to create amusing dramatic situations, a witty literary text. Music played a subordinate role (this is the essential difference between the Parisian operetta and the Viennese): lively, rhythmically spicy couplets and dance divertissements dominated, which were “layered” with extensive prose dialogues. All this lowered the ideological, artistic and actually musical value of operetta performances.

Nevertheless, in the hands of a major artist (and such, undoubtedly, was Offenbach!) the operetta was saturated with elements of satire, acute topicality, and its music acquired an important dramatic significance, being imbued, unlike a comic or “grand” opera, with generally accessible everyday intonations. It is no coincidence that Bizet and Delibes, that is, the most democratic artists of the next generation, who mastered the warehouse modern musical speech, made their debut in the operetta genre. And if Gounod was the first to discover these new intonations (“Faust” was completed in the year of the production of “Orpheus in Hell”), then Offenbach most fully embodied them in his work.

* * *

Jacques Offenbach (his real name was Ebersht) was born on June 20, 1819 in Cologne (Germany) in the family of a devout rabbi; since childhood, he showed interest in music, specialized as a cellist. In 1833 Offenbach moved to Paris. From now on, as was the case with Meyerbeer, France becomes his second home. After graduating from the conservatory, he entered the theater orchestra as a cellist. Offenbach was twenty years old when he made his debut as a composer, which, however, turned out to be unsuccessful. Then he again turned to the cello – he gave concerts in Paris, in the cities of Germany, in London, without neglecting any composer’s work along the way. However, almost everything that he wrote before the 50s has been lost.

During the years 1850-1855, Offenbach was a conductor at the well-known drama theater “Comedie Frangaise”, he wrote a lot of music for performances and attracted both eminent and novice musicians to cooperate (among the first – Meyerbeer, among the second – Gounod). His repeated attempts to get a commission to write an opera were unsuccessful. Offenbach turns to a different kind of activity.

Since the beginning of the 50s, the composer Florimond Herve, one of the founders of the operetta genre, has gained popularity with his witty one-act miniatures. He attracted Delibes and Offenbach to their creation. The latter soon succeeded in eclipsing the glory of Hervé. (According to the figurative remark of one French writer, Aubert stood in front of the doors of the operetta. Herve opened them a little, and Offenbach entered … Florimond Herve (real name – Ronge, 1825-1892) – the author of about a hundred operettas, the best among them is “Mademoiselle Nitouche” (1883) .)

In 1855, Offenbach opened his own theater, called the “Paris Buffs”: here, in a cramped room, he staged cheerful buffoonades and idyllic pastorals with his music, which were performed by two or three actors. A contemporary of the famous French cartoonists Honore Daumier and Paul Gavarni, comedian Eugene Labiche, Offenbach saturated performances with subtle and caustic wit, mocking jokes. He attracted like-minded writers, and if the playwright Scribe in the full sense of the word was a co-author of Meyerbeer’s operas, then in the person of Henri Meilhac and Ludovic Halévy – in the near future authors of the libretto “Carmen” – Offenbach acquired his devoted literary collaborators.

1858 – Offenbach is already under forty – marks a decisive turning point in his fate. This is the year of the premiere of Offenbach’s first great operetta, Orpheus in Hell, which ran for two hundred and eighty-eight performances in a row. (In 1878, the 900th performance took place in Paris!). This is followed, if we name the most famous works, “Geneviève of Brabant” (1859), “Beautiful Helena” (1864), “Bluebeard” (1866), “Paris Life” (1866), “The Duchess of Gerolstein” (1867), ” Pericola” (1868), “Robbers” (1869). The last five years of the Second Empire were the years of Offenbach’s undivided glory, and its climax was 1857: in the center of the magnificent celebrations dedicated to the opening of the World Exhibition, there were performances of “Paris Life”.

Offenbach with the greatest creative tension. He is not only the author of the music for his operettas, but also a co-author of a literary text, a stage director, a conductor, and an entrepreneur for the troupe. Keenly feeling the specifics of the theatre, he completes the scores at rehearsals: shortens what seems to be drawn out, expands, rearranges the numbers. This vigorous activity is complicated by frequent trips to foreign countries, where Offenbach is everywhere accompanied by loud fame.

The collapse of the Second Empire abruptly ended Offenbach’s brilliant career. His operettas leave the stage. In 1875, he was forced to declare himself bankrupt. The state is lost, the theatrical entreprise is dissolved, the author’s income is used to cover debts. To feed his family, Offenbach went on tour to the United States, where in 1876 he conducted garden concerts. And although he creates a new, three-act edition of Pericola (1874), Madame Favard (1878), Daughter of Tambour major (1879) – works that are not only not inferior in their artistic qualities to the previous ones, but even surpass them , open up new, lyrical aspects of the composer’s great talent – he achieves only mediocre success. (By this time, Offenbach’s fame was overshadowed by Charles Lecoq (1832-1918), in whose works a lyrical beginning is put forward to the detriment of parody and cheerful fun instead of an unrestrained cancan. His most famous works are Madame Ango’s Daughter (1872) and Girofle-Girofle (1874) Robert Plunkett’s operetta The Bells of Corneville (1877) was also very popular.)

Offenbach is stricken with a serious heart disease. But in anticipation of his imminent death, he is feverishly working on his latest work – the lyric-comedy opera Tales (in a more accurate translation, “stories”) of Hoffmann. He did not have to attend the premiere: without finishing the score, he died on October 4, 1880.

* * *

Offenbach is the author of over a hundred musical and theatrical works. A large place in his legacy is occupied by interludes, farces, miniature performances-reviews. However, the number of two- or three-act operettas is also in the tens.

The plots of his operettas are diverse: here are antiquity (“Orpheus in Hell”, “Beautiful Elena”), and images of popular fairy tales (“Bluebeard”), and the Middle Ages (“Genevieve of Brabant”), and Peruvian exoticism (“Pericola”), and real events from the French history of the XNUMXth century (“Madame Favard”), and the life of contemporaries (“Parisian life”), etc. But all this external diversity is united by the main theme – the image of modern mores.

Whether it’s old, classic plots or new ones, talking either about fictional countries and events, or about real reality, Offenbach’s contemporaries act everywhere and everywhere, struck by a common ailment – depravity of morals, corruption. To portray such general corruption, Offenbach does not spare colors and sometimes achieves scourging sarcasm, revealing the ulcers of the bourgeois system. However, this is not the case in all of Offenbach’s works. A lot of them are devoted to entertaining, frankly erotic, “cancan” moments, and malicious mockery is often replaced by empty wit. Such a mixture of the socially significant with the boulevard-anecdotal, the satirical with the frivolous is the main contradiction of Offenbach’s theatrical performances.

That is why, of the great legacy of Offenbach, only a few works have survived in the theatrical repertoire. In addition, their literary texts, despite their wit and satirical sharpness, have largely faded, since the allusions to topical facts and events contained in them are outdated. (Because of this, in domestic musical theaters, the texts of Offenbach’s operettas undergo significant, sometimes radical processing.). But the music has not aged. Offenbach’s outstanding talent put him in the forefront of masters of the easy and accessible song and dance genre.

Offenbach’s main source of music is French urban folklore. And although many composers of the comic opera of the XNUMXth century turned to this source, no one before him was able to reveal the features of the national everyday song and dance with such completeness and artistic perfection.

This, however, is not limited to his merits. Offenbach not only recreated the features of urban folklore – and above all the practice of Parisian chansonniers – but also enriched them with the experience of professional artistic classics. Mozart’s lightness and grace, Rossini’s wit and brilliance, Weber’s fiery temperament, the lyricism of Boildieu and Herold, the fascinating, piquant rhythms of Aubert – all this and much more is embodied in Offenbach’s music. However, it is marked by great individual originality.

Melody and rhythm are the defining factors of Offenbach’s music. His melodic generosity is inexhaustible, and his rhythmic inventiveness is exceptionally varied. The lively even sizes of peppy couplet songs are replaced by graceful dance motifs on 6/8, the marching dotted line – by the measured swaying of barcarolles, the temperamental Spanish boleros and fandangos – by the smooth, easy movement of the waltz, etc. The role of dances popular at that time – quadrilles and gallop (see examples 173 a B C D E ). On their basis, Offenbach builds refrains of verses – choral refrains, the dynamics of the development of which is of a vortex nature. These incendiary final ensembles show how fruitfully Offenbach used the experience of comic opera.

Lightness, wit, grace and impetuous impulse – these qualities of Offenbach’s music are reflected in his instrumentation. He combines the simplicity and transparency of the orchestra’s sound with a bright characteristic and subtle color touches that complement the vocal image.

* * *

Despite the noted similarities, there are some differences in Offenbach’s operettas. Three varieties of them can be outlined (we leave aside all other types of little character): these are operetta-parodies, comedies of manners and lyric-comedy operettas. Examples of these types can respectively serve as: “Beautiful Helena”, “Parisian Life” and “Perichole”.

Referring to the plots of antiquity, Offenbach sarcastically parodied them: for example, the mythological singer Orpheus appeared as a loving music teacher, the chaste Eurydice as a frivolous lady of the demimonde, while the omnipotent gods of Olympus turned into helpless and voluptuous elders. With the same ease, Offenbach “reshaped” fairy-tale plots and popular motifs of romantic novels and dramas in a modern way. So he revealed old stories relevant content, but at the same time parodied the usual theatrical techniques and style of opera productions, mocking their ossified conventionality.

The comedies of manners used original plots, in which modern bourgeois relations were more directly and sharply exposed, depicted either in a grotesque refraction (“The Duchess: Gerolsteinskaya”), or in the spirit of a revue review (“Paris Life”).

Finally, in a number of Offenbach’s works, starting with Fortunio’s Song (1861), the lyrical stream was more pronounced – they erased the line that separated the operetta from the comic opera. And the usual mockery left the composer: in the depiction of the love and grief of Pericola or Justine Favard, he conveyed genuine sincerity of feelings, sincerity. This stream grew stronger and stronger in the last years of Offenbach’s life and was completed in The Tales of Hoffmann. The romantic theme about the unattainability of the ideal, about the illusiveness of earthly existence is expressed here in a free-rhapsody form – each act of the opera has its own plot, creates a certain “mood picture” according to the outline of the outlined action.

For many years, Offenbach was worried about this idea. Back in 1851, a five-act performance of The Tales of Hoffmann was shown in a Parisian drama theater. On the basis of a number of short stories by the German romantic writer, the authors of the play, Jules Barbier and Michel Carré, made Hoffmann himself the hero of three love adventures; their participants are the soulless doll Olympia, the mortally ill singer Antonia, the insidious courtesan Juliet. Each adventure ends with a dramatic catastrophe: on the path to happiness, the mysterious adviser Lindorf invariably gets up, changing his appearance. And the image of the beloved eluding the poet is just as changeable… (The basis of the events is the short story by E. T. A. Hoffmann “Don Juan”, in which the writer tells about his meeting with a famous singer. The rest of the images are borrowed from a number of other short stories (“Golden Pot”, “Sandman”, “Advisor “, etc.).)

Offenbach, who had been trying to write a comic opera all his life, was fascinated by the plot of the play, where everyday drama and fantasy were so peculiarly intertwined. But only thirty years later, when the lyrical stream in his work got stronger, he was able to realize his dream, and even then not completely: death prevented him from finishing the work – the clavier Ernest Guiraud instrumented. Since then – the premiere took place in 1881 – The Tales of Hoffmann have firmly entered the world theater repertoire, and the best musical numbers (including the famous barcarolle – see example 173 в) became widely known. (In subsequent years, this only comic opera by Offenbach underwent various revisions: the prose text was shortened, which was replaced by recitatives, individual numbers were rearranged, even acts (their number was reduced from five to three). The most common edition was M. Gregor (1905).)

The artistic merits of Offenbach’s music ensured her long-term, steady popularity – she sounds both in the theater and in concert performance.

A remarkable master of the comedy genre, but at the same time a subtle lyricist, Offenbach is one of the prominent French composers of the second half of the XNUMXth century.

M. Druskin

- List of major operettas by Offenbach →