Homophony |

Greek omoponia – monophony, unison, from omos – one, the same, the same and ponn – sound, voice

A type of polyphony characterized by the division of voices into main and accompanying. This G. fundamentally differs from polyphony, based on the equality of voices. G. and polyphony are contrasted together with monody – monophony without accompaniment (such is the established terminological tradition; however, another use of the terms is also legitimate: G. – as monophony, “one-tone”, monody – as a melody with accompaniment, “singing in one of the voices” ).

The concept of “G.” originated in Dr. Greece, where it meant the unison (“single-tone”) performance of a melody by a voice and an accompanying instrument (as well as its performance by a mixed choir or ensemble in octave doubling). Similar G. is found in Nar. music pl. countries up to the present. time. If unison is periodically broken and restored again, heterophony arises, which is characteristic of ancient cultures, for the practice of nar. performance.

Elements of homophonic writing were inherent in European. music culture is already at an early stage in the development of polyphony. In different epochs they manifest themselves with greater or lesser distinctness (for example, in the practice of faubourdon in the early 14th century). Geography was particularly developed during the period of transition from the Renaissance to the modern era (16th and 17th centuries). The heyday of homophonic writing in the 17th century. was prepared by the development of Europe. music of the 14th-15th and especially the 16th centuries. The most important factors that led to the dominance of G. were: the gradual awareness of the chord as independent. sound complex (and not just the sum of intervals), highlighting the upper voice as the main one (back in the middle of the 16th century there was a rule: “the mode is determined by the tenor”; at the turn of the 16th-17th centuries it was replaced by a new principle: the mode is determined in the upper voice), the distribution of homophonic harmonic. according to the warehouse ital. frottall i villanelle, french. choir. songs.

Music for the lute, a common domestic instrument of the 15th and 16th centuries, played an especially important role in strengthening the guitar. Statement G. also contributed to numerous. lute arrangements of many-headed. polyphonic works. Due to the limitations of polyphonic The possibilities of the lute when transcribing had to simplify the texture by skipping imitations, not to mention more complex polyphonic ones. combinations. In order to preserve the original sound of the work as much as possible, the arranger was forced to leave a maximum of those sounds that were in the polyphonic accompanying the upper voice. lines, but change their function: from the sounds of voices, often equal in rights with the upper voice, they turned into sounds accompanying him.

A similar practice arose towards the end of the 16th century. and the performers – organists and harpsichordists who accompanied the singing. Without a score before their eyes (until the 17th century, musical compositions were distributed only in performing parts), instrumental accompanists were forced to compose original transcriptions of the performed works. in the form of a sequence of lower sounds of music. fabric and simplified recording of other sounds using numbers. Such a record in the form of melodic voices and bass voice with digitization of consonances, which has received special distribution from the beginning. 17th century, naz. general bass and represents the original type of homophonic writing in modern music.

The Protestant Church, which sought to attach to the church. singing of all parishioners, and not just special. trained choristers, also widely used the principle of G. in cult music – the upper, more audible voice became the main one, other voices performed accompaniment close to chordal. This trend also influenced the music. Catholic practice. churches. Finally, the transition from polyphonic. letters to the homophonic, which occurred on the verge of the 16th and 17th centuries, contributed to the ubiquitous household polygon. dance music played at balls and festivities of the 16th century. From Nar. Her song and dance melodies also entered the “high” genres of Europe. music.

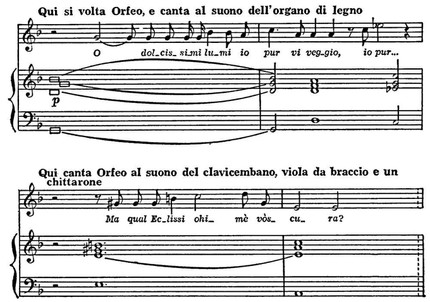

The transition to homophonic writing responded to new aesthetics. requirements arising under the influence of humanistic. European ideas. music Renaissance. The new aesthetics proclaimed the incarnation of the human as its motto. feelings and passions. All muses. means, as well as means of other arts (poetry, theater, dance) were called upon to serve as a true transmission of the spiritual world of a person. Melody began to be regarded as an element of music capable of most naturally and flexibly expressing all the richness of the psychic. human states. This is the most personalized. the melody is perceived especially effectively when the rest of the voices are limited to elementary accompanying figures. Related to this is the development of the Italian bel canto. In opera – new music. In the genre that arose at the turn of the 16th and 17th centuries, homophonic writing was widely used. This was also facilitated by a new attitude towards the expressiveness of the word, which also manifested itself in other genres. Opera scores of the 17th century. usually represent a record of the main. melodic voices from digital. bass denoting accompanying chords. The principle of G. was clearly manifested in operatic recitative:

C. Monteverdi. “Orpheus”.

The most important role in the statement G. also belongs to music for strings. bowed instruments, primarily for the violin.

G.’s wide distribution in Europe. music marked the beginning of the rapid development of harmony in modern. the meaning of this term, the formation of new muses. forms. The dominance of G. cannot be understood literally – as the complete displacement of polyphonic. letters and polyphonic forms. On the 1st floor. 18th century accounts for the work of the greatest polyphonist in the entire world history – J. S. Bach. But G. is still a defining stylistic feature of the whole historical. era in Europe. prof. music (1600-1900).

G.’s development in the 17th-19th centuries conditionally divided into two periods. The first of these (1600-1750) is often defined as the “epoch of the bass general”. This is the period of the formation of G., gradually pushing aside polyphony in almost all fundamentals. genres of vocal and instrument. music. Developing first in parallel with polyphonic. genres and forms, G. gradually gains dominance. position. Early samples of G. late 16th – early. 17th century (songs accompanied by a lute, the first Italian operas – G. Peri, G. Caccini, etc.), with all the value of new stylistic. the devil is still inferior in their arts. values of the highest achievements of the counterpointists of the 15th-16th centuries. But as the methods of homophonic writing were improved and enriched, as new homophonic forms matured, the gypsy gradually reworked and absorbed those arts. wealth, to-rye were accumulated by the old polyphonic. schools. All this prepared one of the climaxes. upsurge of world music. art – the formation of the Viennese classic. style, the heyday of which falls on the end of the 18th – beginning. 19th centuries Having retained all the best in homophonic writing, the Viennese classics enriched its forms.

Developed and polyphonized “accompanying” voices in the symphonies and quartets of Mozart and Beethoven in their mobility and thematic. significance is often not inferior to contra-punctual. lines of old polyphonists. At the same time, the works of the Viennese classics are superior to those of the polyphonic. era with the richness of harmony, flexibility, scale and integrity of the muses. forms, dynamics of development. In Mozart and Beethoven there are also high examples of the synthesis of homophonic and polyphonic. letters, homophonic and polyphonic. forms.

In the beginning. 20th century G.’s dominance was undermined. The development of harmony, which was a solid foundation for homophonic forms, reached its limit, beyond which, as S. I. Taneev pointed out, the binding force of harmonics. relations lost their constructive significance. Therefore, along with the continued development of polyphony (S. S. Prokofiev, M. Ravel), interest in the possibilities of polyphony sharply increases (P. Hindemith, D. D. Shostakovich, A. Schoenberg, A. Webern, I. F. Stravinsky).

The music of the composers of the Viennese classical school concentrated to the greatest extent the valuable features of gypsum. occurred simultaneously with the rise of social thought (the Age of Enlightenment) and to a large extent is its expression. Initial aesthetic. The idea of classicism, which determined the direction of the development of geology, is a new conception of man as a free, active individual, guided by reason (a concept directed against the suppression of the individual, characteristic of the feudal era), and the world as a cognizable whole, rationally organized on the basis of a single principle.

Paphos classic. aesthetics – the victory of reason over elemental forces, the affirmation of the ideal of a free, harmoniously developed person. Hence the joy of affirming correct, reasonable correlations with a clear hierarchy and multi-level gradation of the main and secondary, higher and lower, central and subordinate; emphasizing the typical as an expression of the general validity of the content.

The general structural idea of the rationalist aesthetics of classicism is centralization, dictating the need to highlight the main, optimal, ideal and strict subordination of all other elements of the structure to it. This aesthetics, as an expression of a tendency towards strict structural orderliness, radically transforms the forms of music, objectively directing their development towards the forms of Mozart-Beethoven as the highest type of classical music. structures. The principles of the aesthetics of classicism determine the specific paths of the formation and development of gypsy in the epoch of the 17th and 18th centuries. This is, first of all, the strict fixation of the optimal musical text, the selection of ch. voices as a carrier of the main. content as opposed to the equality of polyphonic. votes, establishing the optimal classic. orc. composition as opposed to the ancient diversity and unsystematic composition; unification and minimization of types of muses. forms as opposed to the freedom of structural types in the music of the previous era; the principle of the unity of the tonic, not obligatory for old music. These principles also include the establishment of the category of the topic (Ch. Theme) as a concentrator. expression of thought in the form of an initial thesis, opposed to its subsequent development (old music did not know this type of theme); highlighting the triad as the main type at the same time. combinations of sounds in polyphony, opposed to modifications and random combinations (old music dealt mainly with combinations of intervals); strengthening the role of the cadence as the place of the highest concentration of the properties of the mode; highlighting the main chord; highlighting the main sound of the chord (main tone); raising squareness with its simplest construction symmetry to the rank of a fundamental structure; the selection of a heavy measure as the top of the metric. hierarchies; in the field of performance – bel canto and the creation of perfect stringed instruments as a reflection of the main. G.’s principle (melody based on a system of optimal resonators).

Developed G. has a specific. features in the structure of its elements and the whole. The division of voices into main and accompanying ones is connected with the contrast between them, primarily rhythmic and linear. Contrasted Ch. in the voice, the bass is, as it were, a “second melody” (Schoenberg’s expression), albeit elementary and undeveloped. The combination of melody and bass always contains polyphony. possibilities (“basic two-voice”, according to Hindemith). The attraction to polyphony is manifested at any rhythmic. and linear animation of homophonic voices, and even more so when counterpoints appear, filling caesuras of imitations, etc. Polyphonization of the accompaniment can lead to quasi-polyphonic. the filling of homophonic forms. The interpenetration of polyphony and grammar can enrich both types of writing; hence nature. the desire to combine the energy of freely developing individualized melodic. lines with richness of homophonic chords and certainty of func. change

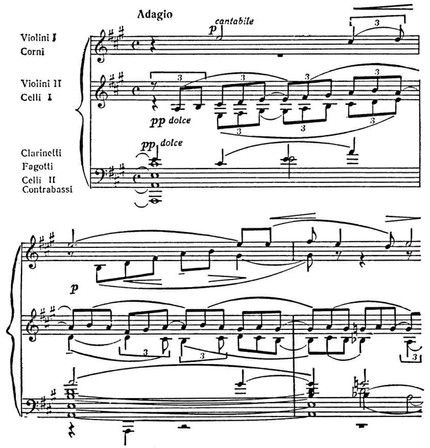

S. V. Rakhmaninov. 2nd symphony, movement III.

The boundary separating G. and polyphony should be considered the attitude to the form: if the music. thought is concentrated in one voice – this is G. (even with polyphonic accompaniment, as in Adagio of Rachmaninov’s 2nd symphony).

If the music thought is distributed among several voices – this is polyphony (even with homophonic accompaniment, as occurs, for example, in Bach; see musical example).

Usually rhythmic. underdevelopment of the voices of homophonic accompaniment (including chord figuration), opposed to rhythmic. richness and diversity melodic voices, contributes to the unification of accompaniment sounds into chord complexes.

J. S. Bach. Mass h-moll, Kyrie (Fugue)

The low mobility of the accompanying voices fixes attention on their interaction as elements of a single sound – a chord. Hence a new (in relation to polyphony) factor of movement and development in the composition – the change of chord complexes. The simplest, and therefore the most natural. the way to implement such sound changes is a uniform alternation, which at the same time allows regular accelerations (accelerations) and slowdowns in accordance with the needs of the muses. development. As a result, prerequisites are created for a special kind of rhythmic. contrast – between the whimsical rhythm in the melody and the measured harmony. accompaniment shifts (the latter may rhythmically coincide with the moves of the homophonic bass or be coordinated with them). Aesthetic the value of “resonant” overtone harmony is most fully revealed in rhythmic conditions. regularity accompanied. Allowing the sounds of accompaniment to naturally combine into regularly changing chords, G. thereby easily allows for the rapid growth of specificity. (actually harmonic) regularities. The desire for renewal when changing sounds as an expression of the effectiveness of harmonics. development and at the same time to the preservation of common sounds for the sake of maintaining its coherence creates objective prerequisites for the use of fourth-fifth relations between chords that best satisfy both requirements. Especially valuable esthetic. the action is possessed by the lower screw move (authentic binomial D – T). Originating initially (still in the depths of the polyphonic forms of the previous era of the 15th-16th centuries) as a characteristic cadence formula, the turnover D – T extends to the rest of the construction, thereby turning the system of old modes into a classical one. two-scale system of major and minor.

Important transformations are also taking place in the melody. In G., the melody rises above the accompanying voices and concentrates in itself the most essential, individualized, ch. part of the subject matter. The change in the role of a monophonic melody in relation to the whole is associated with internal. rearrangement of its constituent elements. Single voice polyphonic the theme is, although a thesis, but a completely finished expression of thought. To reveal this thought, the participation of other voices is not required, no accompaniment is needed. Everything you need for self-sufficiency. the existence of polyphonic themes, located in itself – metrorhythm., tonal harmonic. and syntax. structures, line drawing, melodic. cadence On the other hand, polyphonic. the melody is also intended to be used as one of the polyphonic voices. two, three and four voices. One or more thematically free counterpoints can be attached to it. lines, another polyphonic. a theme or the same melody that enters earlier or later than the given one or with some changes. At the same time, polyphonic melodies connect with each other as integral, fully developed and closed structures.

In contrast, a homophonic melody forms an organic unity with accompaniment. The juiciness and a special kind of sound fullness of a homophonic melody is given by the stream of homophonic bass overtones ascending to it from below; the melody seems to flourish under the influence of overtone “radiation”. harmonic accompaniment chord functions affect the semantic meaning of the melody tones, and express. the effect attributed to a homophonic melody, in def. degree depends on the accompaniment. The latter is not only a special kind of counterpoint to the melody, but also organic. an integral part of the homophonic theme. However, the influence of chordal harmony is also manifested in other ways. The feeling in the mind of the composer of a new homophonic-harmonic. the mode with its chordal extensions precedes the creation of a specific motive. Therefore, the melody is created simultaneously with the unconsciously (or consciously) presented harmonization. This applies not only to homophonic melodics proper (Papageno’s first aria from Mozart’s The Magic Flute), but even to polyphonic ones. the melodics of Bach, who worked in the era of the rise of homophonic writing; harmony clarity. functions fundamentally distinguishes polyphonic. Bach melody from polyphonic. melodics, for example, Palestrina. Therefore, the harmonization of a homophonic melody is, as it were, embedded in itself, the harmony of the accompaniment reveals and complements those functionally harmonic. elements that are inherent in the melody. In this sense, harmony is “a complex system of melos resonators”; “Homophony is nothing but a melody with its acoustically complementary reflection and foundation, a melody with a supporting bass and revealed overtones” (Asafiev).

G development. in Europe music led to the formation and flourishing of a new world of muses. forms, representing one of the highest muses. achievements of our civilization. Inspired by high aesthetics. ideas of classicism, homophonic music. forms unite in themselves will amaze. harmony, scale and completeness of the whole with a richness and variety of details, the highest unity with the dialectics and dynamics of development, the utmost simplicity and clarity of the general principle from the extraordinary. flexibility of its implementation, fundamental uniformity with a huge breadth of application in the most diverse. genres, the universality of the typical with the humanity of the individual. The dialectic of development, which implies a transition from the presentation of the initial thesis (theme) through its negation or antithesis (development) to the approval of Ch. thoughts on new qualities. level, permeates many homophonic forms, revealing itself especially fully in the most developed of them – the sonata form. A characteristic feature of a homophonic theme is the complexity and multi-composition of its structure (a homophonic theme can be written not only as a period, but also in an expanded simple two- or three-part form). This is also manifested in the fact that within the homophonic theme there is such a part (motive, motivic group) that plays the same role in relation to the theme as the theme itself performs in relation to the form as a whole. Between polyphonic. and homophonic themes there is no direct analogy, but there is one between the motive or the main. motive group (it can be the first sentence of a period or part of a sentence) in a homophonic theme and polyphonic. topic. The similarity lies in the fact that both the homophonic motive group and the usually short polyphonic. topic represent the very first statement of the axis. motive material before its repetition (polyphonic counterposition; like the homophonic accompaniment, it is a minor step. motivation material). The fundamental differences between polyphony and G. define two ways of further motivated development of the material: 1) repetition of the main thematic. the nucleus is systematically transferred to other voices, and in this one a minor step appears. thematic. material (polyphonic principle); 2) repetition of the main. thematic. nuclei are carried out in the same voice (as a result of which it becomes the main one), and in others. voices sound secondary. thematic. material (homophonic principle). “Imitation” (as “imitation”, repetition) is also present here, but it seems to occur in one voice and takes on a different form: it is not typical for homophony to preserve melodic inviolability. lines of the motif as a whole. Instead of a “tonal” or linear “real” response, a “harmonic” appears. answer», i.e. repetition of a motive (or motive group) on other harmony, depending on the harmonic. development of the homophonic form. The factor that ensures the recognizability of a motive during repetition is often not the repetition of melodic songs. lines (it can be deformed), and the general outlines are melodic. drawing and metrorhythm. repetition. In a highly developed homophonic form, motivic development can use any (including the most complex) forms of repetition of a motive (reversal, increase, rhythmic variation). Accompanying voices can also take part in this, as developing their own.

By richness, tension and concentration thematically. development of such a G. can far exceed complex polyphonic. forms. However, it does not turn into polyphony, because retains the main features of G.

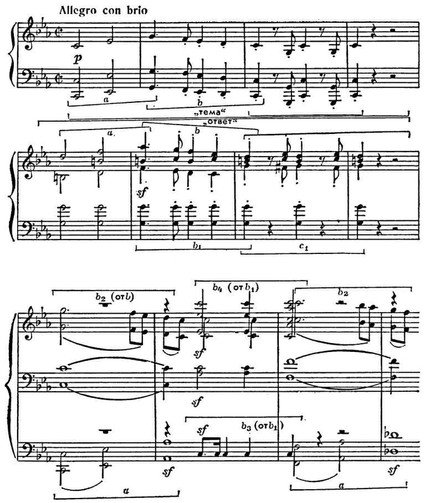

L. Beethoven. 3rd concerto for piano and orchestra, movement I.

First of all, it is the concentration of thought in ch. voice, a type of motivic development (repetitions are correct from the point of view of the chord, but not from the point of view of line drawing), a form common in homophonic music (the 16-bar theme is a period of non-repeated construction).

References: Asafiev B., Musical form as a process, parts 1-2, M., 1930-47, L., 1963; Mazel L., The basic principle of the melodic structure of a homophonic theme, M., 1940 (dissertation, head of the library of the Moscow Conservatory); Helmholtz H. von, Die Lehre von der Tonempfindungen…, Braunschweig, 1863, Rus. trans., St. Petersburg, 1875; Riemann H., Grosse Kompositionslehre, Bd 1, B.-Stuttg., 1902; Kurth E., Grundlagen des linearen Kontrapunkts, Bern, 1917, Rus. per., M., 1931.

Yu. N. Kholopov