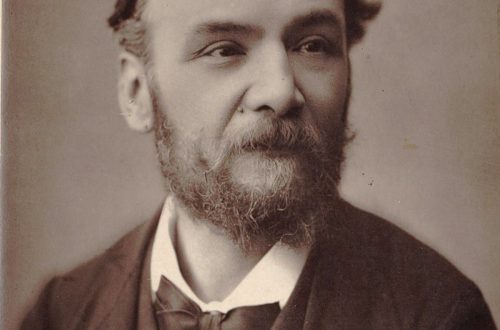

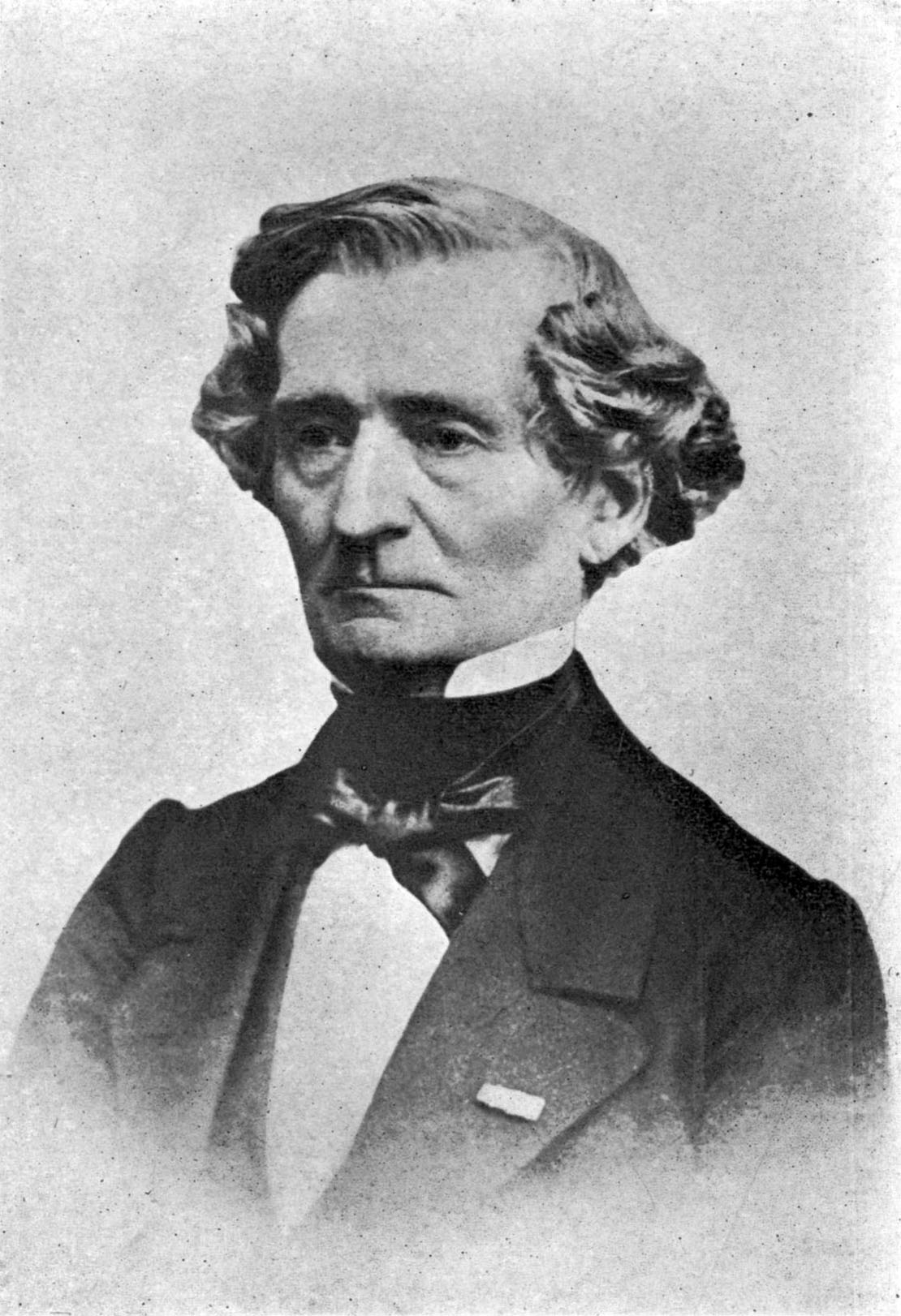

Hector Berlioz |

Hector Berlioz

Let the silver thread of fantasy wind around the chain of rules. R. Schumann

G. Berlioz is one of the greatest composers and the greatest innovators of the 1830th century. He went down in history as the creator of programmatic symphonism, which had a profound and fruitful influence on the entire subsequent development of romantic art. For France, the birth of a national symphonic culture is associated with the name of Berlioz. Berlioz is a musician of a wide profile: composer, conductor, music critic, who defended the advanced, democratic ideals in art, generated by the spiritual atmosphere of the July Revolution of XNUMX. The childhood of the future composer proceeded in a favorable atmosphere. His father, a doctor by profession, instilled in his son a taste for literature, art, and philosophy. Under the influence of his father’s atheistic convictions, his progressive, democratic views, Berlioz’s worldview took shape. But for the musical development of the boy, the conditions of the provincial town were very modest. He learned to play the flute and guitar, and the only musical impression was church singing – Sunday solemn masses, which he loved very much. Berlioz’s passion for music manifested itself in his attempt to compose. These were small plays and romances. The melody of one of the romances was subsequently included as a leitteme in the Fantastic Symphony.

In 1821, Berlioz went to Paris at the insistence of his father to enter the Medical School. But medicine does not attract a young man. Fascinated by music, he dreams of a professional musical education. In the end, Berlioz makes an independent decision to leave science for the sake of art, and this incurs the wrath of his parents, who did not consider music a worthy profession. They deprive their son of any material support, and from now on, the future composer can only rely on himself. However, believing in his destiny, he turns all his strength, energy and enthusiasm to mastering the profession on his own. He lives like Balzac’s heroes from hand to mouth, in attics, but he does not miss a single performance in the opera and spends all his free time in the library, studying the scores.

From 1823, Berlioz began to take private lessons from J. Lesueur, the most prominent composer of the era of the Great French Revolution. It was he who instilled in his student a taste for monumental art forms designed for a mass audience. In 1825, Berlioz, having shown an outstanding organizational talent, arranges a public performance of his first major work, the Great Mass. The following year, he composes the heroic scene “Greek Revolution”, this work opened up a whole direction in his work, associated with revolutionary themes. Feeling the need to acquire deeper professional knowledge, in 1826 Berlioz entered the Paris Conservatory in Lesueur’s composition class and A. Reicha’s counterpoint class. Of great importance for the formation of the aesthetics of a young artist is communication with outstanding representatives of literature and art, including O. Balzac, V. Hugo, G. Heine, T. Gauthier, A. Dumas, George Sand, F. Chopin, F. Liszt, N. Paganini. With Liszt, he is connected by personal friendship, a commonality of creative searches and interests. Subsequently, Liszt would become an ardent promoter of Berlioz’s music.

In 1830, Berlioz created the “Fantastic Symphony” with the subtitle: “An Episode from the Life of an Artist.” It opens a new era of programmatic romantic symphonism, becoming a masterpiece of world musical culture. The program was written by Berlioz and is based on the fact of the composer’s own biography – the romantic story of his love for the English dramatic actress Henrietta Smithson. However, autobiographical motifs in musical generalization acquire the significance of the general romantic theme of the artist’s loneliness in the modern world and, more broadly, the theme of “lost illusions”.

1830 was a turbulent year for Berlioz. Participating for the fourth time in the competition for the Rome Prize, he finally won, submitting the cantata “The Last Night of Sardanapalus” to the jury. The composer finishes his work to the sounds of the uprising that began in Paris and, straight from the competition, goes to the barricades to join the rebels. In the following days, having orchestrated and transcribed the Marseillaise for a double choir, he rehearses it with the people in the squares and streets of Paris.

Berlioz spends 2 years as a Roman scholarship holder at the Villa Medici. Returning from Italy, he develops an active work as a conductor, composer, music critic, but he encounters a complete rejection of his innovative work from the official circles of France. And this predetermined his entire future life, full of hardships and material difficulties. Berlioz’s main source of income is musical critical work. Articles, reviews, musical short stories, feuilletons were subsequently published in several collections: “Music and Musicians”, “Musical Grotesques”, “Evenings in the Orchestra”. The central place in the literary heritage of Berlioz was occupied by Memoirs – the composer’s autobiography, written in a brilliant literary style and giving a broad panorama of the artistic and musical life of Paris in those years. A huge contribution to musicology was the theoretical work of Berlioz “Treatise on Instrumentation” (with the appendix – “Orchestra Conductor”).

In 1834, the second program symphony “Harold in Italy” appeared (based on the poem by J. Byron). The developed part of the solo viola gives this symphony the features of a concerto. 1837 was marked by the birth of one of Berlioz’s greatest creations, the Requiem, created in memory of the victims of the July Revolution. In the history of this genre, Berlioz’s Requiem is a unique work that combines monumental fresco and refined psychological style; marches, songs in the spirit of the music of the French Revolution side by side now with heartfelt romantic lyrics, now with the strict, ascetic style of medieval Gregorian chant. The Requiem was written for a grandiose cast of 200 choristers and an extended orchestra with four additional brass groups. In 1839, Berlioz completed work on the third program symphony Romeo and Juliet (based on the tragedy by W. Shakespeare). This masterpiece of symphonic music, the most original creation of Berlioz, is a synthesis of symphony, opera, oratorio and allows not only concert, but also stage performance.

In 1840, the “Funeral and Triumphal Symphony” appeared, intended for outdoor performance. It is dedicated to the solemn ceremony of transferring the ashes of the heroes of the uprising of 1830 and vividly resurrects the traditions of theatrical performances of the Great French Revolution.

Romeo and Juliet is joined by the dramatic legend The Damnation of Faust (1846), also based on a synthesis of the principles of program symphonism and theatrical stage music. “Faust” by Berlioz is the first musical reading of the philosophical drama of J. W. Goethe, which laid the foundation for numerous subsequent interpretations of it: in the opera (Ch. Gounod), in the symphony (Liszt, G. Mahler), in the symphonic poem (R. Wagner), in vocal and instrumental music (R. Schumann). Peru Berlioz also owns the oratorio trilogy “The Childhood of Christ” (1854), several program overtures (“King Lear” – 1831, “Roman Carnival” – 1844, etc.), 3 operas (“Benvenuto Cellini” – 1838, the dilogy “Trojans” – 1856-63, “Beatrice and Benedict” – 1862) and a number of vocal and instrumental compositions in different genres.

Berlioz lived a tragic life, never achieving recognition in his homeland. The last years of his life were dark and lonely. The only bright memories of the composer were associated with trips to Russia, which he visited twice (1847, 1867-68). Only there did he achieve brilliant success with the public, real recognition among composers and critics. The last letter of the dying Berlioz was addressed to his friend, the famous Russian critic V. Stasov.

L. Kokoreva