Giuseppe Verdi (Giuseppe Verdi) |

Contents

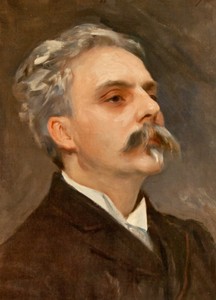

Giuseppe Verdi

Like any great talent. Verdi reflects his nationality and his era. He is the flower of his soil. He is the voice of modern Italy, not lazily dormant or carelessly merry Italy in the comic and pseudo-serious operas of Rossini and Donizetti, not the sentimentally tender and elegiac, weeping Italy of Bellini, but Italy awakened to consciousness, Italy agitated by political storms, Italy , bold and passionate to the fury. A. Serov

No one could feel life better than Verdi. A. Boito

Verdi is a classic of Italian musical culture, one of the most significant composers of the 26th century. His music is characterized by a spark of high civil pathos that does not fade over time, unmistakable accuracy in the embodiment of the most complex processes occurring in the depths of the human soul, nobility, beauty and inexhaustible melody. Peru composer owns XNUMX operas, spiritual and instrumental works, romances. The most significant part of Verdi’s creative heritage is operas, many of which (Rigoletto, La Traviata, Aida, Othello) have been heard from the stages of opera houses around the world for more than a hundred years. Works of other genres, with the exception of the inspired Requiem, are practically unknown, the manuscripts of most of them have been lost.

Verdi, unlike many musicians of the XNUMXth century, did not proclaim his creative principles in program speeches in the press, did not associate his work with the approval of the aesthetics of a particular artistic direction. Nevertheless, his long, difficult, not always impetuous and crowned with victories creative path was directed towards a deeply suffered and conscious goal – the achievement of musical realism in an opera performance. Life in all its variety of conflicts is the overarching theme of the composer’s work. The range of its embodiment was unusually wide – from social conflicts to the confrontation of feelings in the soul of one person. At the same time, Verdi’s art carries a sense of special beauty and harmony. “I like everything in art that is beautiful,” said the composer. His own music also became an example of beautiful, sincere and inspired art.

Clearly aware of his creative tasks, Verdi was tireless in search of the most perfect forms of embodiment of his ideas, extremely demanding of himself, of librettists and performers. He often himself selected the literary basis for the libretto, discussed in detail with the librettists the entire process of its creation. The most fruitful collaboration connected the composer with such librettists as T. Solera, F. Piave, A. Ghislanzoni, A. Boito. Verdi demanded dramatic truth from the singers, he was intolerant of any manifestation of falsehood on stage, senseless virtuosity, not colored by deep feelings, not justified by dramatic action. “…Great talent, soul and stage flair” – these are the qualities that he above all appreciated in performers. “Meaningful, reverent” performance of operas seemed to him necessary; “…when operas cannot be performed in all their integrity – the way they were intended by the composer – it is better not to perform them at all.”

Verdi lived a long life. He was born into the family of a peasant innkeeper. His teachers were the village church organist P. Baistrocchi, then F. Provezi, who led the musical life in Busseto, and the conductor of the Milan theater La Scala V. Lavigna. Already a mature composer, Verdi wrote: “I learned some of the best works of our time, not by studying them, but by hearing them in the theater … I would be lying if I said that in my youth I did not go through a long and rigorous study … my hand is enough strong enough to handle the note as I wish, and confident enough to get the effects I intended most of the time; and if I write anything not according to the rules, it is because the exact rule does not give me what I want, and because I do not consider all the rules adopted to this day unconditionally good.

The first success of the young composer was associated with the production of the opera Oberto at the La Scala theater in Milan in 1839. Three years later, the opera Nebuchadnezzar (Nabucco) was staged in the same theater, which brought the author wide fame (3). The composer’s first operas appeared during the era of revolutionary upsurge in Italy, which was called the era of the Risorgimento (Italian – revival). The struggle for the unification and independence of Italy engulfed the whole people. Verdi could not stand aside. He deeply experienced the victories and defeats of the revolutionary movement, although he did not consider himself a politician. Heroic-patriotic operas of the 1841s. – “Nabucco” (40), “Lombards in the First Crusade” (1841), “Battle of Legnano” (1842) – were a kind of response to revolutionary events. The biblical and historical plots of these operas, far from modern, sang heroism, freedom and independence, and therefore were close to thousands of Italians. “Maestro of the Italian Revolution” – this is how contemporaries called Verdi, whose work became unusually popular.

However, the creative interests of the young composer were not limited to the theme of heroic struggle. In search of new plots, the composer turns to the classics of world literature: V. Hugo (Ernani, 1844), W. Shakespeare (Macbeth, 1847), F. Schiller (Louise Miller, 1849). The expansion of the themes of creativity was accompanied by a search for new musical means, the growth of composer’s skill. The period of creative maturity was marked by a remarkable triad of operas: Rigoletto (1851), Il trovatore (1853), La Traviata (1853). In the work of Verdi, for the first time, a protest against social injustice sounded so openly. The heroes of these operas, endowed with ardent, noble feelings, come into conflict with the generally accepted norms of morality. Turning to such plots was an extremely bold step (Verdi wrote about La Traviata: “The plot is modern. Another would not have taken up this plot, perhaps, because of decency, because of the era, and because of a thousand other stupid prejudices … I I do it with the greatest pleasure).

By the mid 50s. Verdi’s name is widely known throughout the world. The composer concludes contracts not only with Italian theaters. In 1854 he creates the opera “Sicilian Vespers” for the Parisian Grand Opera, a few years later the operas “Simon Boccanegra” (1857) and Un ballo in maschera (1859, for the Italian theaters San Carlo and Appolo) were written. In 1861, by order of the directorate of the St. Petersburg Mariinsky Theater, Verdi created the opera The Force of Destiny. In connection with its production, the composer travels to Russia twice. The opera was not a great success, although Verdi’s music was popular in Russia.

Among the operas of the 60s. The most popular was the opera Don Carlos (1867) based on the drama of the same name by Schiller. The music of “Don Carlos”, saturated with deep psychologism, anticipates the peaks of Verdi’s operatic creativity – “Aida” and “Othello”. Aida was written in 1870 for the opening of a new theater in Cairo. The achievements of all previous operas organically merged in it: the perfection of music, bright coloring, and sharpness of dramaturgy.

Following “Aida” was created “Requiem” (1874), after which there was a long (more than 10 years) silence caused by a crisis in public and musical life. In Italy, there was a widespread passion for the music of R. Wagner, while the national culture was in oblivion. The current situation was not just a struggle of tastes, different aesthetic positions, without which artistic practice is unthinkable, and the development of all art. It was a time of falling priority of national artistic traditions, which was especially deeply experienced by the patriots of Italian art. Verdi reasoned as follows: “Art belongs to all peoples. No one believes in this more firmly than I do. But it develops individually. And if the Germans have a different artistic practice than we do, their art is fundamentally different from ours. We cannot compose like the Germans…”

Thinking about the future fate of Italian music, feeling a huge responsibility for every next step, Verdi set about implementing the concept of the opera Othello (1886), which became a true masterpiece. “Othello” is an unsurpassed interpretation of the Shakespearean story in the operatic genre, a perfect example of a musical and psychological drama, the creation of which the composer went all his life.

The last work of Verdi – the comic opera Falstaff (1892) – surprises with its cheerfulness and impeccable skill; it seems to open a new page in the composer’s work, which, unfortunately, has not been continued. Verdi’s whole life is illuminated by a deep conviction in the correctness of the chosen path: “As far as art is concerned, I have my own thoughts, my own convictions, very clear, very precise, from which I cannot, and should not, refuse.” L. Escudier, one of the composer’s contemporaries, very aptly described him: “Verdi had only three passions. But they reached the greatest strength: love for art, national feeling and friendship. Interest in the passionate and truthful work of Verdi does not weaken. For new generations of music lovers, it invariably remains a classic standard that combines clarity of thought, inspiration of feeling and musical perfection.

A. Zolotykh

- The creative path of Giuseppe Verdi →

- Italian musical culture in the second half of the XNUMXth century →

Opera was at the center of Verdi’s artistic interests. At the earliest stage of his work, in Busseto, he wrote many instrumental works (their manuscripts have been lost), but he never returned to this genre. The exception is the string quartet of 1873, which was not intended by the composer for public performance. In the same youthful years, by the nature of his activity as an organist, Verdi composed sacred music. Towards the end of his career – after the Requiem – he created several more works of this kind (Stabat mater, Te Deum and others). A few romances also belong to the early creative period. He devoted all his energies to opera for more than half a century, from Oberto (1839) to Falstaff (1893).

Verdi wrote twenty-six operas, six of them he gave in a new, significantly modified version. (By decades, these works are placed as follows: late 30s – 40s – 14 operas (+1 in the new edition), 50s – 7 operas (+1 in the new edition), 60s – 2 operas (+2 in the new edition), 70s – 1 opera, 80s – 1 opera (+2 in the new edition), 90s – 1 opera.) Throughout his long life, he remained true to his aesthetic ideals. “I may not be strong enough to achieve what I want, but I know what I am striving for,” Verdi wrote in 1868. These words can describe all his creative activity. But over the years, the artistic ideals of the composer became more distinct, and his skill became more perfect, honed.

Verdi sought to embody the drama “strong, simple, significant.” In 1853, writing La Traviata, he wrote: “I dream of new big, beautiful, varied, bold plots, and extremely bold ones at that.” In another letter (of the same year) we read: “Give me a beautiful, original plot, interesting, with magnificent situations, passions – above all passions! ..”

Truthful and embossed dramatic situations, sharply defined characters – that, according to Verdi, is the main thing in an opera plot. And if in the works of the early, romantic period, the development of situations did not always contribute to the consistent disclosure of characters, then by the 50s the composer clearly realized that the deepening of this connection serves as the basis for creating a vitally truthful musical drama. That is why, having firmly taken the path of realism, Verdi condemned modern Italian opera for monotonous, monotonous plots, routine forms. For the insufficient breadth of showing life’s contradictions, he also condemned his previously written works: “They have scenes of great interest, but there is no diversity. They affect only one side – sublime, if you like – but always the same.

In Verdi’s understanding, opera is unthinkable without the ultimate sharpening of conflict contradictions. Dramatic situations, the composer said, should expose human passions in their characteristic, individual form. Therefore, Verdi strongly opposed any routine in the libretto. In 1851, starting work on Il trovatore, Verdi wrote: “The freer Cammarano (the librettist of the opera.— M. D.) will interpret the form, the better for me, the more satisfied I will be. A year before, having conceived an opera based on the plot of Shakespeare’s King Lear, Verdi pointed out: “Lear should not be made into a drama in the generally accepted form. It would be necessary to find a new form, a larger one, free from prejudice.”

The plot for Verdi is a means of effectively revealing the idea of a work. The composer’s life is permeated with the search for such plots. Starting with Ernani, he persistently seeks literary sources for his operatic ideas. An excellent connoisseur of Italian (and Latin) literature, Verdi was well versed in German, French, and English dramaturgy. His favorite authors are Dante, Shakespeare, Byron, Schiller, Hugo. (About Shakespeare, Verdi wrote in 1865: “He is my favorite writer, whom I know from early childhood and constantly reread.” He wrote three operas on Shakespeare’s plots, dreamed of Hamlet and The Tempest, and returned to work on four times King Lear ”(in 1847, 1849, 1856 and 1869); two operas based on the plots of Byron (the unfinished plan of Cain), Schiller – four, Hugo – two (the plan of Ruy Blas”).)

Verdi’s creative initiative was not limited to the choice of plot. He actively supervised the work of the librettist. “I never wrote operas to ready-made librettos made by someone on the side,” the composer said, “I just can’t understand how a screenwriter can be born who can guess exactly what I can embody in an opera.” Verdi’s extensive correspondence is filled with creative instructions and advice to his literary collaborators. These instructions relate primarily to the scenario plan of the opera. The composer demanded the maximum concentration of the plot development of the literary source, and for this – the reduction of side lines of intrigue, the compression of the text of the drama.

Verdi prescribed to his employees the verbal turns he needed, the rhythm of the verses and the number of words needed for music. He paid special attention to the “key” phrases in the text of the libretto, designed to clearly reveal the content of a particular dramatic situation or character. “It doesn’t matter whether this or that word is, a phrase is needed that will excite, be scenic,” he wrote in 1870 to the librettist of Aida. Improving the libretto of “Othello”, he removed unnecessary, in his opinion, phrases and words, demanded rhythmic diversity in the text, broke the “smoothness” of the verse, which fettered musical development, achieved the utmost expressiveness and conciseness.

Verdi’s bold ideas did not always receive a worthy expression from his literary collaborators. Thus, highly appreciating the libretto of “Rigoletto”, the composer noted weak verses in it. Much did not satisfy him in the dramaturgy of Il trovatore, Sicilian Vespers, Don Carlos. Not having achieved a completely convincing scenario and literary embodiment of his innovative idea in the libretto of King Lear, he was forced to abandon the completion of the opera.

In hard work with the librettists, Verdi finally matured the idea of the composition. He usually started music only after developing a complete literary text of the entire opera.

Verdi said that the most difficult thing for him was “to write fast enough to express a musical idea in the integrity with which it was born in the mind.” He recalled: “When I was young, I often worked non-stop from four in the morning until seven in the evening.” Even at an advanced age, when creating the score of Falstaff, he immediately instrumented the completed large passages, as he was “afraid to forget some orchestral combinations and timbre combinations.”

When creating music, Verdi had in mind the possibilities of its stage embodiment. Connected until the mid-50s with various theaters, he often solved certain issues of musical dramaturgy, depending on the performing forces that the given group had at its disposal. Moreover, Verdi was interested not only in the vocal qualities of the singers. In 1857, before the premiere of “Simon Boccanegra”, he pointed out: “The role of Paolo is very important, it is absolutely necessary to find a baritone who would be a good actor.” Back in 1848, in connection with the planned production of Macbeth in Naples, Verdi rejected the singer Tadolini offered to him, since her vocal and stage abilities did not fit the intended role: “Tadolini has a magnificent, clear, transparent, powerful voice, and I I would like a voice for a lady, deaf, harsh, gloomy. Tadolini has something angelic in her voice, and I would like something diabolical in the lady’s voice.

In learning his operas, right up to Falstaff, Verdi took an active part, intervening in the work of the conductor, paying especially much attention to the singers, carefully going through the parts with them. Thus, the singer Barbieri-Nini, who performed the role of Lady Macbeth at the premiere of 1847, testified that the composer rehearsed a duet with her up to 150 times, achieving the means of vocal expressiveness he needed. He worked just as demandingly at the age of 74 with the famous tenor Francesco Tamagno, who played the role of Othello.

Verdi paid special attention to the stage interpretation of the opera. His correspondence contains many valuable statements on these issues. “All the forces of the stage provide dramatic expressiveness,” wrote Verdi, “and not just the musical transmission of cavatinas, duets, finals, etc.” In connection with the production of The Force of Destiny in 1869, he complained about the critic, who wrote only about the vocal side of the performer: they say…”. Noting the musicality of the performers, the composer emphasized: “Opera—understand me correctly—that is, stage musical drama, was given very mediocrely. It is against this taking the music off the stage and Verdi protested: participating in the learning and staging of his works, he demanded the truth of feelings and actions both in singing and in stage movement. Verdi argued that only under the condition of the dramatic unity of all means of musical stage expression can an opera performance be complete.

Thus, starting from the choice of plot in hard work with the librettist, when creating music, during its stage embodiment – at all stages of working on an opera, from the conception to staging, the master’s imperious will manifested itself, which confidently led Italian art native to him to heights. realism.

* * *

Verdi’s operatic ideals were formed as a result of many years of creative work, great practical work, and persistent quest. He knew well the state of contemporary musical theater in Europe. Spending a lot of time abroad, Verdi got acquainted with the best troupes in Europe – from St. Petersburg to Paris, Vienna, London, Madrid. He was familiar with the operas of the greatest contemporary composers. (Probably Verdi heard Glinka’s operas in St. Petersburg. In the personal library of the Italian composer there was a clavier of “The Stone Guest” by Dargomyzhsky.). Verdi evaluated them with the same degree of criticality with which he approached his own work. And often he did not so much assimilate the artistic achievements of other national cultures, but processed them in his own way, overcoming their influence.

This is how he treated the musical and stage traditions of the French theater: they were well known to him, if only because three of his works (“Sicilian Vespers”, “Don Carlos”, the second edition of “Macbeth”) were written for the Parisian stage. The same was his attitude towards Wagner, whose operas, mostly of the middle period, he knew, and some of them highly appreciated (Lohengrin, Valkyrie), but Verdi creatively argued with both Meyerbeer and Wagner. He did not belittle their importance for the development of French or German musical culture, but rejected the possibility of slavish imitation of them. Verdi wrote: “If the Germans, proceeding from Bach, reach Wagner, then they act like genuine Germans. But we, the descendants of Palestrina, imitating Wagner, are committing a musical crime, creating unnecessary and even harmful art. “We feel differently,” he added.

The question of Wagner’s influence has been especially acute in Italy since the 60s; many young composers succumbed to him (The most zealous admirers of Wagner in Italy were Liszt’s student, the composer J. Sgambatti, the conductor G. Martucci, A. Boito (at the beginning of his creative career, before meeting Verdi) and others.). Verdi noted bitterly: “All of us — composers, critics, the public — have done everything possible to abandon our musical nationality. Here we are at a quiet harbor … one more step, and we will be Germanized in this, as in everything else. It was hard and painful for him to hear from the lips of young people and some critics the words that his former operas were outdated, did not meet modern requirements, and the current ones, starting with Aida, follow in the footsteps of Wagner. “What an honor, after a forty-year creative career, to end up as a wannabe!” Verdi exclaimed angrily.

But he did not reject the value of Wagner’s artistic conquests. The German composer made him think about many things, and above all about the role of the orchestra in opera, which was underestimated by Italian composers of the first half of the XNUMXth century (including Verdi himself at an early stage of his work), about increasing the importance of harmony (and this important means of musical expression neglected by the authors of the Italian opera) and, finally, about the development of principles of end-to-end development to overcome the dismemberment of the forms of the number structure.

However, for all these questions, the most important for the musical dramaturgy of the opera of the second half of the century, Verdi found their solutions other than Wagner’s. In addition, he outlined them even before he got acquainted with the works of the brilliant German composer. For example, the use of “timbre dramaturgy” in the scene of the apparition of spirits in “Macbeth” or in the depiction of an ominous thunderstorm in “Rigoletto”, the use of divisi strings in a high register in the introduction to the last act of “La Traviata” or trombones in the Miserere of “Il Trovatore” – these are bold, individual methods of instrumentation are found regardless of Wagner. And if we talk about anyone’s influence on the Verdi orchestra, then we should rather have in mind Berlioz, whom he greatly appreciated and with whom he was on friendly terms from the beginning of the 60s.

Verdi was just as independent in his search for a fusion of the principles of song-ariose (bel canto) and declamatory (parlante). He developed his own special “mixed manner” (stilo misto), which served as the basis for him to create free forms of monologue or dialogic scenes. Rigoletto’s aria “Courtesans, fiend of vice” or the spiritual duel between Germont and Violetta were also written before acquaintance with Wagner’s operas. Of course, familiarization with them helped Verdi to boldly develop new principles of dramaturgy, which in particular affected his harmonic language, which became more complex and flexible. But there are cardinal differences between the creative principles of Wagner and Verdi. They are clearly visible in their attitude to the role of the vocal element in the opera.

With all the attention that Verdi paid to the orchestra in his last compositions, he recognized the vocal and melodic factor as leading. So, regarding the early operas by Puccini, Verdi wrote in 1892: “It seems to me that the symphonic principle prevails here. This in itself is not bad, but one must be careful: an opera is an opera, and a symphony is a symphony.

“Voice and melody,” Verdi said, “for me will always be the most important thing.” He ardently defended this position, believing that typical national features of Italian music find expression in it. In his project for the reform of public education, presented to the government in 1861, Verdi advocated the organization of free evening singing schools, for every possible stimulation of vocal music at home. Ten years later, he appealed to young composers to study classical Italian vocal literature, including the works of Palestrina. In the assimilation of the peculiarities of the singing culture of the people, Verdi saw the key to the successful development of national traditions of musical art. However, the content that he invested in the concepts of “melody” and “melodiousness” changed.

In the years of creative maturity, he sharply opposed those who interpreted these concepts one-sidedly. In 1871, Verdi wrote: “One cannot be only a melodist in music! There is something more than melody, than harmony – in fact – music itself! .. “. Or in a letter from 1882: “Melody, harmony, recitation, passionate singing, orchestral effects and colors are nothing but means. Make good music with these tools!..” In the heat of the controversy, Verdi even expressed judgments that sounded paradoxical in his mouth: “Melodies are not made from scales, trills or groupetto … There are, for example, melodies in the bard choir (from Bellini’s Norma.— M. D.), the prayer of Moses (from the opera of the same name by Rossini.— M. D.), etc., but they are not in the cavatinas of The Barber of Seville, The Thieving Magpie, Semiramis, etc. — What is it? “Whatever you want, just not melodies” (from a letter of 1875.)

What caused such a sharp attack against Rossini’s operatic melodies by such a consistent supporter and staunch propagandist of the national musical traditions of Italy, which was Verdi? Other tasks that were put forward by the new content of his operas. In singing, he wanted to hear “a combination of the old with a new recitation”, and in the opera – a deep and multifaceted identification of the individual features of specific images and dramatic situations. This is what he was striving for, updating the intonational structure of Italian music.

But in the approach of Wagner and Verdi to the problems of operatic dramaturgy, in addition to national differences, other style artistic direction. Starting as a romantic, Verdi emerged as the greatest master of realistic opera, while Wagner was and remained a romantic, although in his works of different creative periods the features of realism appeared to a greater or lesser extent. This ultimately determines the difference in the ideas that excited them, the themes, images, which forced Verdi to oppose Wagner’s “musical drama» your understanding «musical stage drama».

* * *

Not all contemporaries understood the greatness of Verdi’s creative deeds. However, it would be wrong to believe that the majority of Italian musicians in the second half of the 1834th century were under the influence of Wagner. Verdi had his supporters and allies in the struggle for national operatic ideals. His older contemporary Saverio Mercadante also continued to work, as a follower of Verdi, Amilcare Ponchielli (1886-1874, the best opera Gioconda – 1851; he was Puccini’s teacher) achieved significant success. A brilliant galaxy of singers improved by performing the works of Verdi: Francesco Tamagno (1905-1856), Mattia Battistini (1928-1873), Enrico Caruso (1921-1867) and others. The outstanding conductor Arturo Toscanini (1957-90) was brought up on these works. Finally, in the 1863s, a number of young Italian composers came to the fore, using Verdi’s traditions in their own way. These are Pietro Mascagni (1945-1890, the opera Rural Honor – 1858), Ruggero Leoncavallo (1919-1892, the opera Pagliacci – 1858) and the most talented of them – Giacomo Puccini (1924-1893; the first significant success is the opera “Manon”, 1896; the best works: “La Boheme” – 1900, “Tosca” – 1904, “Cio-Cio-San” – XNUMX). (They are joined by Umberto Giordano, Alfredo Catalani, Francesco Cilea and others.)

The work of these composers is characterized by an appeal to a modern theme, which distinguishes them from Verdi, who after La Traviata did not give a direct embodiment of modern subjects.

The basis for the artistic searches of young musicians was the literary movement of the 80s, headed by the writer Giovanni Varga and called “verismo” (verismo means “truth”, “truthfulness”, “reliability” in Italian). In their works, verists mainly depicted life the ruined peasantry (especially the south of Italy) and the urban poor, that is, the destitute social lower classes, crushed by the progressive course of the development of capitalism. In the merciless denunciation of the negative aspects of bourgeois society, the progressive significance of the work of verists was revealed. But the addiction to “bloody” plots, the transfer of emphatically sensual moments, the exposure of the physiological, bestial qualities of a person led to naturalism, to a depleted depiction of reality.

To a certain extent, this contradiction is also characteristic of verist composers. Verdi could not sympathize with the manifestations of naturalism in their operas. Back in 1876, he wrote: “It’s not bad to imitate reality, but it’s even better to create reality … By copying it, you can only make a photograph, not a picture.” But Verdi could not help but welcome the desire of young authors to remain faithful to the precepts of the Italian opera school. The new content they turned to demanded other means of expression and principles of dramaturgy – more dynamic, highly dramatic, nervously excited, impetuous.

However, in the best works of the verists, the continuity with the music of Verdi is clearly felt. This is especially noticeable in the work of Puccini.

Thus, at a new stage, in the conditions of a different theme and other plots, the highly humanistic, democratic ideals of the great Italian genius illuminated the paths for the further development of Russian opera art.

M. Druskin

Compositions:

operas – Oberto, Count of San Bonifacio (1833-37, staged in 1839, La Scala Theatre, Milan), King for an Hour (Un giorno di regno, later called Imaginary Stanislaus, 1840, there those), Nebuchadnezzar (Nabucco, 1841, staged in 1842, ibid), Lombards in the First Crusade (1842, staged in 1843, ibid; 2nd edition, under the title Jerusalem, 1847, Grand Opera Theater, Paris), Ernani (1844, theater La Fenice, Venice), Two Foscari (1844, theater Argentina, Rome), Jeanne d’Arc (1845, theater La Scala, Milan), Alzira (1845, theater San Carlo, Naples) , Attila (1846, La Fenice Theatre, Venice), Macbeth (1847, Pergola Theatre, Florence; 2nd edition, 1865, Lyric Theatre, Paris), Robbers (1847, Haymarket Theatre, London ), The Corsair (1848, Teatro Grande, Trieste), Battle of Legnano (1849, Teatro Argentina, Rome; with revised libretto, titled The Siege of Harlem, 1861), Louise Miller (1849, Teatro San Carlo, Naples), Stiffelio (1850, Grande Theatre, Trieste; 2nd edition, under the title Garol d, 1857, Teatro Nuovo, Rimini), Rigoletto (1851, Teatro La Fenice, Venice), Troubadour (1853, Teatro Apollo, Rome), Traviata (1853, Teatro La Fenice, Venice), Sicilian Vespers (French libretto by E. Scribe and Ch. Duveyrier, 1854, staged in 1855, Grand Opera, Paris; 2nd edition titled “Giovanna Guzman”, Italian libretto by E. Caimi, 1856, Milan), Simone Boccanegra (libretto by F. M. Piave, 1857, Teatro La Fenice, Venice; 2nd edition, libretto revised by A Boito, 1881, La Scala Theatre, Milan), Un ballo in maschera (1859, Apollo Theatre, Rome), The Force of Destiny (libretto by Piave, 1862, Mariinsky Theatre, Petersburg, Italian troupe; 2nd edition, libretto revised by A. Ghislanzoni, 1869, Teatro alla Scala, Milan), Don Carlos (French libretto by J. Mery and C. du Locle, 1867, Grand Opera, Paris; 2nd edition, Italian libretto, revised A. Ghislanzoni, 1884, La Scala Theatre, Milan), Aida (1870, staged in 1871, Opera Theatre, Cairo), Otello (1886, staged in 1887, La Scala Theatre, Milan), Falstaff ( 1892, staged in 1893, ibid.), for choir and piano – Sound, trumpet (words by G. Mameli, 1848), Anthem of the Nations (cantata, words by A. Boito, performed in 1862, the Covent Garden Theater, London), spiritual works – Requiem (for 4 soloists, choir and orchestra, performed in 1874, Milan), Pater Noster (text by Dante, for 5-voice choir, performed in 1880, Milan), Ave Maria (text by Dante, for soprano and string orchestra, performed in 1880, Milan), Four Sacred Pieces (Ave Maria, for 4-voice choir; Stabat Mater, for 4-voice choir and orchestra; Le laudi alla Vergine Maria, for 4-voice female choir; Te Deum, for choir and orchestra ; 1889-97, performed in 1898, Paris); for voice and piano – 6 romances (1838), Exile (ballad for bass, 1839), Seduction (ballad for bass, 1839), Album – six romances (1845), Stornell (1869), and others; instrumental ensembles – string quartet (e-moll, performed in 1873, Naples), etc.