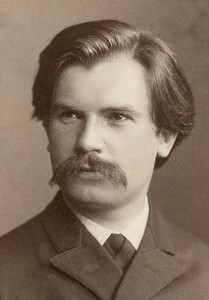

Gioachino Rossini |

Gioachino Rossini

But the blue evening is getting dark, It’s time for us to the opera soon; There is the delightful Rossini, Europe’s darling – Orpheus. Ignoring harsh criticism He is eternally the same; forever new. He pours sounds – they boil. They flow, they burn. Like young kisses Everything is in bliss, in the flame of love, Like a hissed ai A stream and splashes of gold … A. Pushkin

Among the Italian composers of the XIX century. Rossini occupies a special place. The beginning of his creative path falls at a time when the operatic art of Italy, which not so long ago dominated Europe, began to lose ground. Opera-buffa was drowning in mindless entertainment, and opera-seria degenerated into a stilted and meaningless performance. Rossini not only revived and reformed Italian opera, but also had a huge impact on the development of the entire European operatic art of the last century. “Divine Maestro” – so called the great Italian composer G. Heine, who saw in Rossini “the sun of Italy, squandering its sonorous rays around the world.”

Rossini was born into the family of a poor orchestral musician and a provincial opera singer. With a traveling troupe, the parents wandered around various cities of the country, and the future composer from childhood was already familiar with the life and customs that dominated the Italian opera houses. An ardent temperament, a mocking mind, a sharp tongue coexisted in the nature of little Gioacchino with subtle musicality, excellent hearing and an extraordinary memory.

In 1806, after several years of unsystematic studies in music and singing, Rossini entered the Bologna Music Lyceum. There, the future composer studied cello, violin and piano. Classes with the famous church composer S. Mattei in theory and composition, intensive self-education, enthusiastic study of the music of J. Haydn and W. A. Mozart – all this allowed Rossini to leave the lyceum as a cultured musician who mastered the skill of composing well.

Already at the very beginning of his career, Rossini showed a particularly pronounced penchant for musical theater. He wrote his first opera Demetrio and Polibio at the age of 14. Since 1810, the composer has been composing several operas of various genres every year, gradually gaining fame in wide opera circles and conquering the stages of the largest Italian theaters: Fenice in Venice, San Carlo in Naples, La Scala in Milan.

The year 1813 was a turning point in the composer’s operatic work, 2 compositions staged that year – “Italian in Algiers” (onepa-buffa) and “Tancred” (heroic opera) – determined the main paths of his further work. The success of the works was caused not only by excellent music, but also by the content of the libretto, imbued with patriotic sentiments, so consonant with the national liberation movement for the reunification of Italy, which unfolded at that time. The public outcry caused by Rossini’s operas, the creation of the “Hymn of Independence” at the request of the patriots of Bologna, as well as participation in the demonstrations of the freedom fighters in Italy – all this led to a long-term secret police supervision, which was established for the composer. He did not at all consider himself a politically minded person and wrote in one of his letters: “I never interfered in politics. I was a musician, and it never occurred to me to become anyone else, even if I experienced the liveliest participation in what was happening in the world, and especially in the fate of my homeland.

After “Italian in Algiers” and “Tancred” Rossini’s work quickly goes uphill and after 3 years reaches one of the peaks. At the beginning of 1816, the premiere of The Barber of Seville took place in Rome. Written in just 20 days, this opera was not only the highest achievement of Rossini’s comedic-satirical genius, but also the culminating point in almost a century of development of the opera-buifa genre.

With The Barber of Seville, the composer’s fame went beyond Italy. Brilliant Rossini style refreshed the art of Europe with ebullient cheerfulness, sparkling wit, foaming passion. “My The Barber is becoming more and more successful every day,” wrote Rossini, “and even to the most inveterate opponents of the new school he managed to suck up so that they, against their will, begin to love this clever guy more and more.” The fanatically enthusiastic and superficial attitude towards Rossini’s music of the aristocratic public and the bourgeois nobility contributed to the emergence of many opponents for the composer. However, among the European artistic intelligentsia there were also serious connoisseurs of his work. E. Delacroix, O. Balzac, A. Musset, F. Hegel, L. Beethoven, F. Schubert, M. Glinka were under the spell of Rossin’s music. And even K. M. Weber and G. Berlioz, who occupied a critical position in relation to Rossini, did not doubt his genius. “After the death of Napoleon, there was another person who is constantly being talked about everywhere: in Moscow and Naples, in London and Vienna, in Paris and Calcutta,” Stendhal wrote about Rossini.

Gradually the composer loses interest in onepe-buffa. Written soon in this genre, “Cinderella” does not show the listeners new creative revelations of the composer. The opera The Thieving Magpie, composed in 1817, goes beyond the limits of the comedy genre altogether, becoming a model of everyday musical realistic drama. Since that time, Rossini began to pay more attention to heroic-dramatic operas. Following Othello, legendary historical works appear: Moses, The Lady of the Lake, Mohammed II.

After the first Italian revolution (1820-21) and its brutal suppression by the Austrian troops, Rossini went on tour to Vienna with a Neapolitan opera troupe. The Viennese triumphs further strengthened the composer’s European fame. Returning for a short time to Italy for the production of Semiramide (1823), Rossini went to London and then to Paris. He lives there until 1836. In Paris, the composer heads the Italian Opera House, attracting his young compatriots to work in it; reworks for the Grand Opera the operas Moses and Mohammed II (the latter was staged in Paris under the title The Siege of Corinth); writes, commissioned by the Opera Comique, the elegant opera Le Comte Ory; and finally, in August 1829, he puts on the stage of the Grand Opera his last masterpiece – the opera “William Tell”, which had a huge impact on the subsequent development of the genre of Italian heroic opera in the work of V. Bellini, G. Donizetti and G. Verdi.

“William Tell” completed the musical stage work of Rossini. The operatic silence of the brilliant maestro that followed him, who had about 40 operas behind him, was called by contemporaries the mystery of the century, surrounding this circumstance with all sorts of conjectures. The composer himself later wrote: “How early, as a barely mature young man, I began to compose, just as early, earlier than anyone could have foreseen it, I stopped writing. It always happens in life: whoever starts early must, according to the laws of nature, finish early.

However, even after ceasing to write operas, Rossini continued to remain in the center of attention of the European musical community. All of Paris listened to the composer’s aptly critical word, his personality attracted musicians, poets, and artists like a magnet. R. Wagner met with him, C. Saint-Saens was proud of his communication with Rossini, Liszt showed his works to the Italian maestro, V. Stasov spoke enthusiastically about meeting with him.

In the years following William Tell, Rossini created the magnificent spiritual work Stabat mater, the Little Solemn Mass and the Song of the Titans, an original collection of vocal works called Evenings Musical, and a cycle of piano pieces bearing the playful title Sins of Old Age. . From 1836 to 1856 Rossini, surrounded by glory and honors, lived in Italy. There he directed the Bologna Musical Lyceum and was engaged in teaching activities. Returning then to Paris, he remained there until the end of his days.

12 years after the death of the composer, his ashes were transferred to his homeland and buried in the pantheon of the Church of Santa Croce in Florence, next to the remains of Michelangelo and Galileo.

Rossini bequeathed his entire fortune to the benefit of the culture and art of his native city of Pesaro. Nowadays, Rossini opera festivals are regularly held here, among the participants of which one can meet the names of the largest contemporary musicians.

I. Vetlitsyna

- Rossini’s creative path →

- Artistic searches of Rossini in the field of “serious opera” →

Born into a family of musicians: his father was a trumpeter, his mother was a singer. Learns to play various musical instruments, singing. He studies composition at the Bologna School of Music under the direction of Padre Mattei; did not complete the course. From 1812 to 1815 he worked for the theaters of Venice and Milan: the “Italian in Algiers” had a special success. By order of the impresario Barbaia (Rossini marries his girlfriend, the soprano Isabella Colbran), he creates sixteen operas until 1823. He moved to Paris, where he became director of the Théâtre d’Italien, the first composer of the king and general inspector of singing in France. Says goodbye to the activities of the opera composer in 1829 after the production of “William Tell”. After parting with Colbrand, he marries Olympia Pelissier, reorganizes the Bologna Music Lyceum, staying in Italy until 1848, when political storms again bring him to Paris: his villa in Passy becomes one of the centers of artistic life.

The one who was called the “last classic” and to whom the public applauded as the king of the comic genre, in the very first operas demonstrated the grace and brilliance of melodic inspiration, the naturalness and lightness of the rhythm, which gave singing, in which the traditions of the XNUMXth century were weakened, a more sincere and human character. The composer, pretending to adapt himself to modern theatrical customs, could, however, rebel against them, hindering, for example, the virtuosic arbitrariness of the performers or moderating it.

The most significant innovation for Italy at that time was the important role of the orchestra, which, thanks to Rossini, became alive, mobile and brilliant (we note the magnificent form of the overtures, which really tune in to a certain perception). A cheerful penchant for a kind of orchestral hedonism stems from the fact that each instrument, used in accordance with its technical capabilities, is identified with singing and even speech. At the same time, Rossini can safely assert that the words should serve the music, and not vice versa, without detracting from the meaning of the text, but, on the contrary, using it in a new way, freshly and often shifting to typical rhythmic patterns – while the orchestra freely accompanies speech, creating a clear melodic and symphonic relief and performing expressive or pictorial functions.

Rossini’s genius immediately showed itself in the genre of opera seria with the production of Tancredi in 1813, which brought the author his first great success with the public thanks to melodic discoveries with their sublime and gentle lyricism, as well as unconstrained instrumental development, which owes its origin to the comic genre. The links between these two operatic genres are indeed very close in Rossini and even determine the amazing showiness of his serious genre. In the same 1813, he also presented a masterpiece, but in the comic genre, in the spirit of the old Neapolitan comic opera – “Italian in Algiers”. This is an opera rich in echoes from Cimarosa, but as if enlivened by the stormy energy of the characters, especially manifested in the final crescendo, the first by Rossini, who will then use it as an aphrodisiac when creating paradoxical or unrestrainedly cheerful situations.

The caustic, earthly mind of the composer finds in fun an outlet for his craving for caricature and his healthy enthusiasm, which does not allow him to fall into either the conservatism of classicism or the extremes of romanticism.

He will achieve a very thorough comic result in The Barber of Seville, and a decade later he will come to the elegance of The Comte Ory. In addition, in the serious genre, Rossini will move with great strides towards an opera of ever greater perfection and depth: from the heterogeneous, but ardent and nostalgic “Lady of the Lake” to the tragedy “Semiramide”, which ends the Italian period of the composer, full of dizzying vocalizations and mysterious phenomena in the Baroque taste, to the “Siege of Corinth” with its choirs, to the solemn descriptiveness and sacred monumentality of “Moses” and, finally, to “William Tell”.

If it is still surprising that Rossini achieved these achievements in the field of opera in just twenty years, it is equally striking that the silence that followed such a fruitful period and lasted for forty years, which is considered one of the most incomprehensible cases in the history of culture, – either by an almost demonstrative detachment, worthy, however, of this mysterious mind, or by evidence of his legendary laziness, of course, more fictional than real, given the composer’s ability to work in his best years. Few noticed that he was increasingly seized by a neurotic craving for solitude, crowding out a tendency to fun.

Rossini, however, did not stop composing, although he cut off all contact with the general public, addressing himself mainly to a small group of guests, regulars at his home evenings. The inspiration of the latest spiritual and chamber works has gradually emerged in our days, arousing the interest of not only connoisseurs: real masterpieces have been discovered. The most brilliant part of Rossini’s legacy is still operas, in which he was the legislator of the future Italian school, creating a huge number of models used by subsequent composers.

In order to better highlight the characteristic features of such a great talent, a new critical edition of his operas was undertaken at the initiative of the Center for the Study of Rossini in Pesaro.

G. Marchesi (translated by E. Greceanii)

Compositions by Rossini:

operas – Demetrio and Polibio (Demetrio e Polibio, 1806, post. 1812, tr. “Balle”, Rome), Promissory note for marriage (La cambiale di matrimonio, 1810, tr. “San Moise”, Venice), Strange case (L’equivoco stravagante, 1811, “Teatro del Corso” , Bologna), Happy Deception (L’inganno felice, 1812, tr “San Moise”, Venice), Cyrus in Babylon (Ciro in Babilonia, 1812, tr “Municipale”, Ferrara), Silk Stairs (La scala di seta, 1812, tr “San Moise”, Venice), Touchstone (La pietra del parugone, 1812, tr “La Scala”, Milan), Chance makes a thief, or Mixed suitcases (L’occasione fa il ladro, ossia Il cambio della valigia, 1812, tr San Moise, Venice), Signor Bruschino, or Accidental Son (Il signor Bruschino, ossia Il figlio per azzardo, 1813, ibid.), Tancredi , 1813, tr Fenice, Venice), Italian in Algeria (L’italiana in Algeri, 1813, tr San Benedetto, Venice), Aurelian in Palmyra (Aureliano in Palmira, 1813, tr “La Scala”, Milan), Turks in Italy (Il turco in Italia, 1814, ibid.), Sigismondo (Sigismondo, 1814, tr “Fenice”, Venice),Elizabeth, Queen of England (Elisabetta, regina d’Inghilterra, 1815, tr “San Carlo”, Naples), Torvaldo and Dorliska (Torvaldo e Dorliska, 1815, tr “Balle”, Rome), Almaviva, or Vain precaution (Almaviva, ossia L’inutile precauzione; known under the name The Barber of Seville – Il barbiere di Siviglia, 1816, tr Argentina, Rome), Newspaper, or Marriage by Competition (La gazzetta, ossia Il matrimonio per concorso, 1816, tr Fiorentini, Naples), Othello, or the Venetian Moor (Otello, ossia Il toro di Venezia, 1816, tr “Del Fondo”, Naples), Cinderella, or the Triumph of Virtue (Cenerentola, ossia La bonta in trionfo, 1817, tr “Balle”, Rome) , Magpie thief (La gazza ladra, 1817, tr “La Scala”, Milan), Armida (Armida, 1817, tr “San Carlo”, Naples), Adelaide of Burgundy (Adelaide di Borgogna, 1817, t -r “Argentina”, Rome), Moses in Egypt (Mosè in Egitto, 1818, tr “San Carlo”, Naples; French. Ed. – under the title Moses and Pharaoh, or Crossing the Red Sea – Moïse et Pharaon, ou Le passage de la mer rouge, 1827, “King. Academy of Music and Dance, Paris), Adina, or Caliph of Baghdad (Adina, ossia Il califfo di Bagdad, 1818, post. 1826, tr “San Carlo”, Lisbon), Ricciardo and Zoraida (Ricciardo e Zoraide, 1818, tr “San Carlo”, Naples), Hermione (Ermione, 1819, ibid), Eduardo and Christina ( Eduardo e Cristina, 1819, tr San Benedetto, Venice), Lady of the Lake (La donna del lago, 1819, tr San Carlo, Naples), Bianca and Faliero, or the Council of Three (Bianca e Faliero, ossia II consiglio dei tre, 1819, La Scala shopping mall, Milan), Mohammed II (Maometto II, 1820, San Carlo shopping mall, Naples; French. Ed. – under the title The siege of Corinth – Le siège de Corinthe, 1826, “King. Academy of Music and Dance, Paris), Matilde di Shabran, or Beauty and the Iron Heart (Matilde di Shabran, ossia Bellezza e cuor di ferro, 1821, t-r “Apollo”, Rome), Zelmira (Zelmira, 1822, t- r “San Carlo”, Naples), Semiramide (Semiramide, 1823, tr “Fenice”, Venice), Journey to Reims, or the Hotel of the Golden Lily (Il viaggio a Reims, ossia L’albergo del giglio d’oro, 1825, Theater Italien, Paris), Count Ory (Le comte Ory, 1828, King. pasticcio (from excerpts from Rossini’s operas) – Ivanhoe (Ivanhoe, 1826, tr “Odeon”, Paris), Testament (Le testament, 1827, ibid.), Cinderella (1830, tr “Covent Garden”, London), Robert Bruce (1846, King’s Academy of Music and Dance, Paris), We’re Going to Paris (Andremo a Parigi, 1848, Theatre Italien, Paris), Funny Accident (Un curioso accidente, 1859, ibid.); for soloists, choir and orchestra – Hymn of Independence (Inno dell`Indipendenza, 1815, tr “Contavalli”, Bologna), cantatas – Aurora (1815, ed. 1955, Moscow), The Wedding of Thetis and Peleus (Le nozze di Teti e di Peleo, 1816, Del Fondo shopping mall, Naples), Sincere tribute (Il vero omaggio, 1822, Verona) , A happy omen (L’augurio felice, 1822, ibid), Bard (Il bardo, 1822), Holy Alliance (La Santa alleanza, 1822), Complaint of the Muses about the death of Lord Byron (Il pianto delie Muse in morte di Lord Byron, 1824, Almack Hall, London), Choir of the Municipal Guard of Bologna (Coro dedicato alla guardia civica di Bologna, instrumented by D. Liverani, 1848, Bologna), Hymn to Napoleon III and his valiant people (Hymne b Napoleon et a son vaillant peuple, 1867, Palace of Industry, Paris), National Anthem (The national hymn, English national anthem, 1867, Birmingham); for orchestra – symphonies (D-dur, 1808; Es-dur, 1809, used as an overture to the farce A promissory note for marriage), Serenade (1829), Military March (Marcia militare, 1853); for instruments and orchestra – Variations for obligate instruments F-dur (Variazioni a piu strumenti obligati, for clarinet, 2 violins, viol, cello, 1809), Variations C-dur (for clarinet, 1810); for brass band – fanfare for 4 trumpets (1827), 3 marches (1837, Fontainebleau), Crown of Italy (La corona d’Italia, fanfare for military orchestra, offering to Victor Emmanuel II, 1868); chamber instrumental ensembles – duets for horns (1805), 12 waltzes for 2 flutes (1827), 6 sonatas for 2 skr., vlc. and k-bass (1804), 5 strings. quartets (1806-08), 6 quartets for flute, clarinet, horn and bassoon (1808-09), Theme and Variations for flute, trumpet, horn and bassoon (1812); for piano – Waltz (1823), Congress of Verona (Il congresso di Verona, 4 hands, 1823), Neptune’s Palace (La reggia di Nettuno, 4 hands, 1823), Soul of Purgatory (L’vme du Purgatoire, 1832); for soloists and choir – cantata Complaint of Harmony about the death of Orpheus (Il pianto d’Armonia sulla morte di Orfeo, for tenor, 1808), Death of Dido (La morte di Didone, stage monologue, 1811, Spanish 1818, tr “San Benedetto” , Venice), cantata (for 3 soloists, 1819, tr “San Carlo”, Naples), Partenope and Higea (for 3 soloists, 1819, ibid.), Gratitude (La riconoscenza, for 4 soloists, 1821, ibid. same); for voice and orchestra – Cantata The Shepherd’s Offering (Omaggio pastorale, for 3 voices, for the solemn opening of the bust of Antonio Canova, 1823, Treviso), Song of the Titans (Le chant des Titans, for 4 basses in unison, 1859, Spanish 1861, Paris); for voice and piano – Cantatas Elie and Irene (for 2 voices, 1814) and Joan of Arc (1832), Musical Evenings (Soirees musicales, 8 ariettes and 4 duets, 1835); 3 wok quartet (1826-27); Soprano Exercises (Gorgheggi e solfeggi per soprano. Vocalizzi e solfeggi per rendere la voce agile ed apprendere a cantare secondo il gusto moderno, 1827); 14 wok albums. and instr. pieces and ensembles, united under the name. Sins of old age (Péchés de vieillesse: Album of Italian songs – Album per canto italiano, French album – Album francais, Restrained pieces – Morceaux reserves, Four appetizers and four desserts – Quatre hors d’oeuvres et quatre mendiants, for fp., Album for fp ., skr., vlch., harmonium and horn; many others, 1855-68, Paris, not published); spiritual music – Graduate (for 3 male voices, 1808), Mass (for male voices, 1808, Spanish in Ravenna), Laudamus (c. 1808), Qui tollis (c. 1808), Solemn Mass (Messa solenne, joint. with P. Raimondi, 1819, Spanish 1820, Church of San Fernando, Naples), Cantemus Domino (for 8 voices with piano or organ, 1832, Spanish 1873), Ave Maria (for 4 voices, 1832, Spanish 1873 ), Quoniam (for bass and orchestra, 1832), Stabat mater (for 4 voices, choir and orchestra, 1831-32, 2nd ed. 1841-42, edited 1842, Ventadour Hall, Paris), 3 choirs – Faith, Hope, Mercy (La foi, L’esperance, La charite, for women’s choir and piano, 1844), Tantum ergo (for 2 tenors and bass), 1847, Church of San Francesco dei Minori Conventuali, Bologna) , About Salutaris Hostia (for 4 voices 1857), Little Solemn Mass (Petite messe solennelle, for 4 voices, choir, harmonium and piano, 1863, Spanish 1864, in the house of Count Pilet-Ville, Paris), the same (for soloists, choir and orchestra., 1864, Spanish 1869, “Italien Theatre”, Paris), Requiem Melody (Chant de Requiem, for contralto and piano, 1864 XNUMX); music for drama theater performances – Oedipus in Colon (to the tragedy of Sophocles, 14 numbers for soloists, choir and orchestra, 1815-16?).