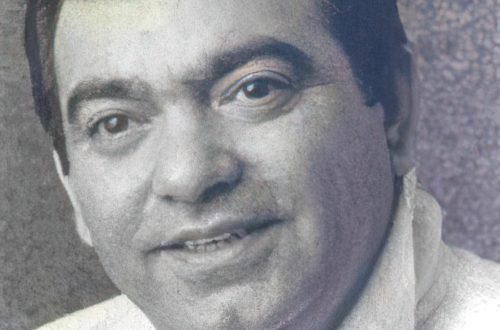

Enrico Caruso (Enrico Caruso) |

Enrico Caruso

“He had the Order of the Legion of Honor and the English Victorian Order, the German Order of the Red Eagle and a gold medal on the ribbon of Frederick the Great, the Order of an Officer of the Italian Crown, the Belgian and Spanish orders, even a soldier’s icon in a silver salary, which was called the Russian “Order of St. Nicholas”, diamond cufflinks – a gift from the Emperor of All Russia, a gold box from the Duke of Vendôme, rubies and diamonds from the English king … – writes A. Filippov. “His antics are still talked about to this day. One of the singers lost her lace pantaloons right during the aria, but managed to shove them under the bed with her foot. She was happy for a short time. Caruso lifted his pants, straightened them and with a ceremonial bow brought the lady … The auditorium exploded with laughter. For dinner with the Spanish king, he came with his pasta, assuring that they were much tastier, and invited the guests to taste. During a government reception, he congratulated the President of the United States with the words: “I am happy for you, Your Excellency, you are almost as famous as I am.” In English, he knew only a few words, which was known to very few: thanks to his artistry and good pronunciation, he always easily got out of a difficult situation. Only once did ignorance of the language lead to a curiosity: the singer was informed of the sudden death of one of his acquaintances, to which Caruso beamed with a smile and joyfully exclaimed: “It’s great, when you see him, say hello from me!”

He left behind about seven million (for the beginning of the century this is crazy money), estates in Italy and America, several houses in the United States and Europe, collections of the rarest coins and antiques, hundreds of expensive suits (each one came with a pair of lacquered boots).

And here is what the Polish singer J. Vaida-Korolevich, who performed with a brilliant singer, writes: “Enrico Caruso, an Italian born and raised in magical Naples, surrounded by wondrous nature, the Italian sky and the scorching sun, was very impressionable, impulsive and quick-tempered. The strength of his talent was made up of three main features: the first is a bewitching hot, passionate voice that cannot be compared with any other. The beauty of his timbre was not in the evenness of the sound, but, on the contrary, in the richness and variety of colors. Caruso expressed all the feelings and experiences with his voice – at times it seemed that the game and stage action were superfluous for him. The second feature of Caruso’s talent is a palette of feelings, emotions, psychological nuances in singing, boundless in its richness; finally, the third feature is his huge, spontaneous and subconscious dramatic talent. I write “subconscious” because his stage images were not the result of careful, painstaking work, were not refined and finished to the smallest detail, but as if they were immediately born from his hot southern heart.

Enrico Caruso was born on February 24, 1873 on the outskirts of Naples, in the San Giovanello area, in a working class family. “From the age of nine, he began to sing, with his sonorous, beautiful contralto immediately attracted attention,” Caruso later recalled. His first performances took place close to home in the small church of San Giovanello. He graduated from Enrico only primary school. With regard to musical training, he received the minimum necessary knowledge in the field of music and singing, acquired from local teachers.

As a teenager, Enrico entered the factory where his father worked. But he continued to sing, which, however, is not surprising for Italy. Caruso even took part in a theatrical production – the musical farce The Robbers in the Garden of Don Raffaele.

The further path of Caruso is described by A. Filippov:

“In Italy at that time, 360 tenors of the first class were registered, 44 of which were considered famous. Several hundred singers of a lower rank breathed into the back of their heads. With such competition, Caruso had few prospects: it is quite possible that his lot would have remained life in the slums with a bunch of half-starved children and a career as a street soloist, with a hat in his hand bypassing listeners. But then, as is usually the case in novels, His Majesty Chance came to the rescue.

In the opera The Friend of Francesco, staged by the music lover Morelli at his own expense, Caruso had a chance to play an elderly father (a sixty-year-old tenor sang the part of his son). And everyone heard that the voice of the “dad” is much more beautiful than that of the “son”. Enrico was immediately invited to the Italian troupe, going on tour to Cairo. There, Caruso went through a tough “baptism of fire” (he happened to sing without knowing the role, attaching a sheet with the text to the back of his partner) and for the first time earned decent money, famously skipping them with the dancers of the local variety show. Caruso returned to the hotel in the morning riding on a donkey, covered in mud: drunk, he fell into the Nile and miraculously escaped from a crocodile. A merry feast was only the beginning of a “long journey” – while touring in Sicily, he went on stage half-drunk, instead of “fate” he sang “gulba” (in Italian they are also consonant), and this almost cost him his career.

In Livorno, he sings Pagliatsev by Leoncavallo – the first success, then an invitation to Milan and the role of a Russian count with a sonorous Slavic name Boris Ivanov in Giordano’s opera “Fedora” … “

The admiration of critics knew no bounds: “One of the finest tenors we have ever heard!” Milan welcomed the singer, who was not yet known in the operatic capital of Italy.

On January 15, 1899, Petersburg already heard Caruso for the first time in La Traviata. Caruso, embarrassed and touched by the warm reception, responding to the numerous praises of Russian listeners, said: “Oh, don’t thank me – thank Verdi!” “Caruso was a wonderful Radamès, who aroused everyone’s attention with his beautiful voice, thanks to which one can assume that this artist will soon be in the first row of outstanding modern tenors,” critic N.F. wrote in his review. Solovyov.

From Russia, Caruso went overseas to Buenos Aires; then sings in Rome and Milan. After a stunning success at La Scala, where Caruso sang in Donizetti’s L’elisir d’amore, even Arturo Toscanini, who was very stingy with praise, conducted the opera, could not stand it and, embracing Caruso, said. “My God! If this Neapolitan continues to sing like that, he will make the whole world talk about him!”

On the evening of November 23, 1903, Caruso made his New York debut at the Metropolitan Theatre. He sang in Rigoletto. The famous singer conquers the American public immediately and forever. The director of the theater was then Enri Ebey, who immediately signed a contract with Caruso for a whole year.

When Giulio Gatti-Casazza from Ferrara later became the director of the Metropolitan Theater, Caruso’s fee began to grow steadily every year. As a result, he received so much that other theaters in the world could no longer compete with New Yorkers.

Commander Giulio Gatti-Casazza directed the Metropolitan Theater for fifteen years. He was cunning and prudent. And if sometimes there were exclamations that a fee of forty, fifty thousand lire for one performance was excessive, that not a single artist in the world received such a fee, then the director only chuckled.

“Caruso,” he said, “is the least worth of the impresario, so no fee can be excessive for him.”

And he was right. When Caruso participated in the performance, the directorate increased ticket prices at their discretion. Traders appeared who bought tickets at any price, and then resold them for three, four and even ten times more!

“In America, Caruso was always successful from the very beginning,” writes V. Tortorelli. His influence on the public grew day by day. The chronicle of the Metropolitan Theater states that no other artist had such success here. The appearance of Caruso’s name on posters was every time a big event in the city. It caused complications for the theater management: the large hall of the theater could not accommodate everyone. It was necessary to open the theater two, three, or even four hours before the start of the performance, so that the temperamental audience of the gallery would calmly take their seats. It ended with the fact that the theater for evening performances with the participation of Caruso began to open at ten o’clock in the morning. Spectators with handbags and baskets filled with provisions occupied the most convenient places. Almost twelve hours before, people came to hear the singer’s magical, bewitching voice (performances started then at nine o’clock in the evening).

Caruso was busy with the Met only during the season; at the end of it, he traveled to numerous other opera houses, which besieged him with invitations. Where only the singer did not perform: in Cuba, in Mexico City, in Rio de Janeiro and Buffalo.

For example, since October 1912, Caruso made a grandiose tour of the cities of Europe: he sang in Hungary, Spain, France, England and Holland. In these countries, as in North and South America, he was awaited by an enthusiastic reception of joyful and tremulous listeners.

Once Caruso sang in the opera “Carmen” on the stage of the theater “Colon” in Buenos Aires. At the end of Jose’s arioso, false notes sounded in the orchestra. They remained unnoticed by the public, but did not escape the conductor. Leaving the console, he, beside himself with rage, went to the orchestra with the intention of reprimanding. However, the conductor noticed that many soloists of the orchestra were crying, and did not dare to say a word. Embarrassed, he returned to his seat. And here are the impressions of the impresario about this performance, published in the New York weekly Follia:

“Until now, I thought that the rate of 35 lire that Caruso requested for one evening performance was excessive, but now I am convinced that for such a completely unattainable artist, no compensation would be excessive. Bring tears to the musicians! Think about it! It’s Orpheus!

Success came to Caruso not only thanks to his magical voice. He knew the parties and his partners in the play well. This allowed him to better understand the work and intentions of the composer and to live organically on stage. “In the theater I’m just a singer and actor,” said Caruso, “but in order to show the public that I’m not one or the other, but a real character conceived by the composer, I have to think and feel exactly like the person I had in mind composer”.

December 24, 1920 Caruso performed in the six hundred and seventh, and his last, opera performance at the Metropolitan. The singer felt very bad: during the whole performance he experienced excruciating, piercing pain in his side, he was very feverish. Calling on all his will to help, he sang the five acts of The Cardinal’s Daughter. Despite the cruel illness, the great artist kept on stage firmly and confidently. The Americans sitting in the hall, not knowing about his tragedy, applauded furiously, shouted “encore”, not suspecting that they had heard the last song of the conqueror of hearts.

Caruso went to Italy and courageously fought the disease, but on August 2, 1921, the singer died.