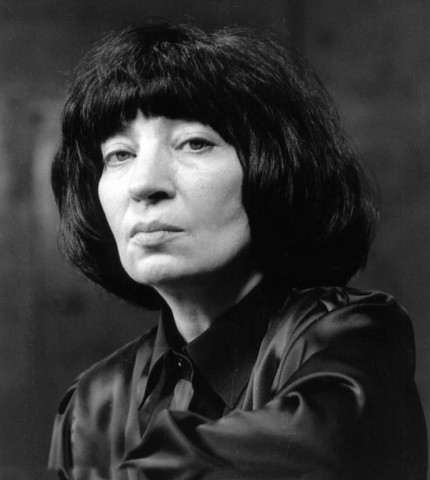

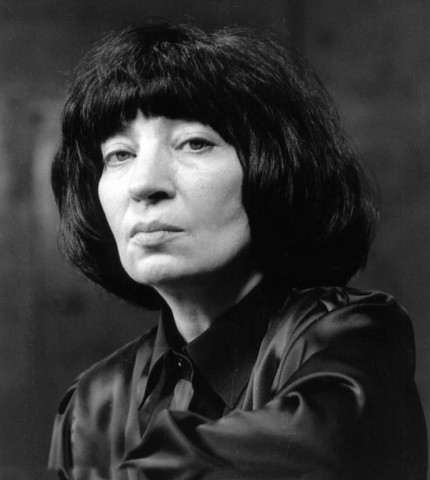

Eliso Konstantinovna Virsaladze |

Eliso Virsaladze

Eliso Konstantinovna Virsaladze is the granddaughter of Anastasia Davidovna Virsaladze, a prominent Georgian artist and piano teacher in the past. (In the class of Anastasia Davidovna, Lev Vlasenko, Dmitry Bashkirov and other subsequently famous musicians began their journey.) Eliso spent his childhood and youth in his grandmother’s family. She took her first piano lessons from her, attended her class at the Tbilisi Central Music School, and graduated from her conservatory. “In the beginning, my grandmother worked with me sporadically, from time to time,” recalls Virsaladze. – She had a lot of students and finding time even for her granddaughter was not an easy task. And the prospects for working with me, one must think, were at first not too clear and defined. Then my attitude changed. Apparently, grandmother herself was carried away by our lessons … “

From time to time Heinrich Gustavovich Neuhaus came to Tbilisi. He was friendly with Anastasia Davidovna, advised her best pets. Genrikh Gustavovich listened, more than once, to young Eliso, helping her with advice and critical remarks, encouraging her. Later, in the early sixties, she happened to be in Neuhaus’s class at the Moscow Conservatory. But this will happen shortly before the death of a wonderful musician.

Virsaladze Sr., say those who knew her closely, had something like a set of fundamental principles in teaching – rules developed by many years of observation, reflection, and experience. There is nothing more pernicious than the pursuit of quick success with a novice performer, she believed. There is nothing worse than forced learning: one who tries to forcefully pull a young plant out of the ground runs the risk of uprooting it – and only … Eliso received a consistent, thorough, comprehensively thought-out upbringing. Much was done to expand her spiritual horizons – from childhood she was introduced to books and foreign languages. Its development in the piano-performing sphere was also unconventional – bypassing the traditional collections of technical exercises for compulsory finger gymnastics, etc. Anastasia Davidovna was convinced that it is quite possible to work out pianistic skills using only artistic material for this. “In my work with my granddaughter Eliso Virsaladze,” she once wrote, “I decided not to resort to etudes at all, except for etudes by Chopin and Liszt, but chose the appropriate (artistic.— Mr. C.) repertoire … and paid special attention to the works of Mozart, allowing the maximum polish the craft“(My discharge. – Mr. C.) (Virsaladze A. Piano Pedagogy in Georgia and the Traditions of the Esipova School // Outstanding Pianists-Teachers on Piano Art. – M.; L., 1966. P. 166.). Eliso says that during her school years she went through many works by Mozart; the music of Haydn and Beethoven occupied no less place in its curricula. In the future, we will still talk about her skill, about the magnificent “polished” of this skill; for now, we note that under it is a deeply laid foundation of classical plays.

And one more thing is characteristic of the formation of Virsaladze as an artist – the early acquired right to independence. “I loved to do everything myself – whether it’s right or wrong, but on my own … Probably, this is in my character.

And of course, I was lucky to have teachers: I never knew what pedagogical dictatorship was.” They say that the best teacher in art is the one who strives to be in the end unnecessary student. (V. I. Nemirovich-Danchenko once dropped a remarkable phrase: “The crown of the director’s creative efforts,” he said, “becomes simply superfluous for the actor, with whom he had done all the necessary work before.”) Both Anastasia Davidovna and Neuhaus that is how they understood their ultimate goal and task.

Being a tenth grader, Virsaladze gave the first solo concert in her life. The program was composed of two sonatas by Mozart, several intermezzos by Brahms, Schumann’s Eighth Novelette and Rachmaninov’s Polka. In the near future, her public appearances became more frequent. In 1957, the 15-year-old pianist became the winner at the Republican Youth Festival; in 1959 she won a laureate diploma at the World Festival of Youth and Students in Vienna. A few years later, she won the third prize at the Tchaikovsky Competition (1962) – a prize obtained in the most difficult competition, where her rivals were John Ogdon, Susin Starr, Alexei Nasedkin, Jean-Bernard Pommier … And one more victory on Virsaladze’s account – in Zwickau , at the International Schumann Competition (1966). The author of “Carnival” will be included in the future among those deeply revered and successfully performed by her; there was an undoubted pattern in her winning the gold medal at the competition …

In 1966-1968, Virsaladze studied as a postgraduate student at the Moscow Conservatory under Ya. I. Zak. She has the brightest memories of this time: “The charm of Yakov Izrailevich was felt by everyone who studied with him. In addition, I had a special relationship with our professor – sometimes it seemed to me that I had the right to talk about some kind of inner closeness to him as an artist. This is so important – the creative “compatibility” of a teacher and a student … ” Soon Virsaladze herself will begin to teach, she will have her first students – different characters, personalities. And if she happens to be asked: “Does she like pedagogy?”, She usually answers: “Yes, if I feel a creative relationship with the one I teach,” referring as an illustration to her studies with Ya. I. Zak.

… A few more years have passed. Meetings with the public became the most important thing in Virsaladze’s life. Specialists and music critics began to look at it more and more closely. In one of the foreign reviews of her concerto, they wrote: “To those who first see the thin, graceful figure of this woman behind the piano, it is difficult to imagine that so much will will appear in her playing … she hypnotizes the hall from the very first notes she takes.” The observation is correct. If you try to find something most characteristic in the appearance of Virsaladze, you must start with her performing will.

Almost everything that Virsaladze-interpreter conceives, is brought to life by her (praise, which is usually addressed only to the best of the best). Indeed, creative plans – the most daring, daring, impressive – can be created by many; they are realized only by those who have a firm, well-trained stage will. When Virsaladze, with impeccable accuracy, without a single miss, plays the most difficult passage on the piano keyboard, this shows not only her excellent professional and technical dexterity, but also her enviable pop self-control, endurance, strong-willed attitude. When it culminates in a piece of music, then its peak is at the one and only necessary point – this is also not only knowledge of the laws of form, but also something else psychologically more complex and important. The will of a musician performing in public is in the purity and infallibility of his playing, in the certainty of the rhythmic step, in the stability of the tempo. It is in the victory over nervousness, the vagaries of moods – in, as G. G. Neuhaus says, in order “not to shed on the way from behind the scenes to the stage not a drop of precious excitement with the works …” (Neigauz G. G. Passion, intellect, technique // Named after Tchaikovsky: About the 2nd International Tchaikovsky Competition of Performing Musicians. – M., 1966. P. 133.). Probably, there is no artist who would be unfamiliar with hesitation, self-doubt – and Virsaladze is no exception. Only in someone you see these doubts, you guess about them; she never has.

Will and in the most emotional tonus artist’s art. In her character performance expression. Here, for example, Ravel’s Sonatina is a work that appears from time to time in her programs. It happens that other pianists do their best to envelop this music (such is the tradition!) with a haze of melancholy, sentimental sensitivity; in Virsaladze, on the contrary, there is not even a hint of melancholic relaxation here. Or, say, Schubert’s impromptu – C minor, G-flat major (both Op. 90), A-flat major (Op. 142). Is it really so rare that they are presented to the regulars of piano parties in a languid, elegiacly pampered manner? Virsaladze in Schubert’s impromptu, as in Ravel, has decisiveness and firmness of will, an affirmative tone of musical statements, nobility and severity of emotional coloring. Her feelings are the more restrained, the stronger they are, the temperament is the more disciplined, the hotter, the affected passions in the music revealed by her to the listener. “Real, great art,” V. V. Sofronitsky reasoned at one time, “is like this: red-hot, boiling lava, and on top of seven armor” (Memories of Sofronitsky. – M., 1970. S. 288.). Virsaladze’s game is art the present: Sofronitsky’s words could become a kind of epigraph to many of her stage interpretations.

And one more distinguishing feature of the pianist: she loves proportion, symmetry and does not like what could break them. Her interpretation of Schumann’s C major Fantasy, now recognized as one of the best numbers in her repertoire, is indicative. A work, as you know, is one of the most difficult: it is very difficult to “build” it, under the hands of many musicians, and by no means inexperienced, it sometimes breaks up into separate episodes, fragments, sections. But not at Virsaladze’s performances. Fantasy in its transmission is an elegant unity of the whole, almost perfect balance, “fitting” of all elements of a complex sound structure. This is because Virsaladze is a born master of musical architectonics. (It is no coincidence that she emphasized her closeness to Ya. I. Zak.) And therefore, we repeat, that she knows how to cement and organize material by an effort of will.

The pianist plays a variety of music, including (in many!) created by romantic composers. Schumann’s place in her stage activities has already been discussed; Virsaladze is also an outstanding interpreter of Chopin – his mazurkas, etudes, waltzes, nocturnes, ballads, B minor sonata, both piano concertos. Effective in her performance are Liszt’s compositions – Three Concert Etudes, Spanish Rhapsody; she finds a lot of successful, truly impressive in Brahms – the First Sonata, the Variations on a Theme of Handel, the Second Piano Concerto. And yet, with all the achievements of the artist in this repertoire, in terms of her personality, aesthetic preferences, and the nature of her performance, she belongs to artists not so much romantic as classical formations.

The law of harmony reigns unshakably in her art. In almost every interpretation, a delicate balance of mind and feeling is achieved. Everything spontaneous, uncontrollable is resolutely removed and clear, strictly proportional, carefully “made” is cultivated – down to the smallest details and particulars. (I. S. Turgenev once made a curious statement: “Talent is a detail,” he wrote.) These are the well-known and recognized signs of the “classical” in musical performance, and Virsaladze has them. Isn’t it symptomatic: she addresses dozens of authors, representatives of different eras and trends; and yet, trying to single out the name most dear to her, it would be necessary to name the first name of Mozart. Her first steps in music were connected with this composer – her pianistic adolescence and youth; his own works to this day are at the center of the list of works performed by the artist.

Deeply revering the classics (not only Mozart), Virsaladze also willingly performs compositions by Bach (Italian and D minor concertos), Haydn (sonatas, Concerto major) and Beethoven. Her artistic Beethovenian includes the Appassionata and a number of other sonatas by the great German composer, all piano concertos, variation cycles, chamber music (with Natalia Gutman and other musicians). In these programs, Virsaladze knows almost no failures.

However, we must pay tribute to the artist, she generally rarely fails. She has a very large margin of safety in the game, both psychological and vocational. Once she said that she brings a work to the stage only when she knows that she can not learn it specially – and she will still succeed, no matter how difficult it may be.

Therefore, her game is little subject to chance. Although she, of course, has happy and unhappy days. Sometimes, say, she is not in the mood, then you can see how the constructive side of her performance is exposed, only a well-adjusted sound structure, logical design, technical infallibility of the game begin to be noticed. At other moments, Virsaladze’s control over what he performs becomes excessively rigid, “screwed up” – in some ways this damages open and direct experience. It happens that one wants to feel in her playing a sharper, burning, piercing expression – when it sounds, for example, the coda of Chopin’s C-sharp minor scherzo or some of his etudes – Twelfth (“Revolutionary”), Twenty-second (octave), Twenty-third or Twenty-fourth.

They say that the outstanding Russian artist V. A. Serov considered a painting to be successful only when he found in it some kind of, as he said, “magic mistake”. In “Memoirs” by V. E. Meyerhold, one can read: “At first, it took a long time to paint just a good portrait … then suddenly Serov came running, washed everything away and painted a new portrait on this canvas with the same magical mistake that he spoke about. It is curious that in order to create such a portrait, he had to first sketch the correct portrait. Virsaladze has a lot of stage works, which she can rightfully consider “successful” – bright, original, inspired. And yet, to be frank, no, no, yes, and among her interpretations there are those that resemble just a “correct portrait”.

In the middle and at the end of the eighties, Virsaladze’s repertoire was replenished with a number of new works. Brahms’ Second Sonata, some of Beethoven’s early sonata opuses, appears in her programs for the first time. The whole cycle “Mozart’s Piano Concertos” sounds (previously only partially performed on the stage). Together with other musicians, Eliso Konstantinovna takes part in the performance of A. Schnittke’s Quintet, M. Mansuryan’s Trio, O. Taktakishvili’s Cello Sonata, as well as some other chamber compositions. Finally, the big event in her creative biography was the performance of Liszt’s B minor sonata in the 1986/87 season – it had a wide resonance and undoubtedly deserved it …

The pianist’s tours are becoming more and more frequent and intense. Her performances in the USA (1988) are a resounding success, she opens many new concert “venues” for herself both in the USSR and in other countries.

“It seems that not so little has been done in recent years,” says Eliso Konstantinovna. “At the same time, I am not left with a feeling of some kind of internal split. On the one hand, I devote today to the piano, perhaps even more time and effort than before. On the other hand, I constantly feel that this is not enough … ”Psychologists have such a category – insatiable, unsatisfied need. The more a person devotes to his work, the more he invests in it labor and soul, the stronger, the more acute becomes his desire to do more and more; the second increases in direct proportion to the first. So it is with every true artist. Virsaladze is no exception.

She, as an artist, has an excellent press: critics, both Soviet and foreign, never tire of admiring her performance. Fellow musicians treat Virsaladze with sincere respect, appreciating her serious and honest attitude to art, her rejection of everything petty, vain, and, of course, paying tribute to her invariably high professionalism. Nevertheless, we repeat, some kind of dissatisfaction is constantly felt in her herself – regardless of the external attributes of success.

“I think dissatisfaction with what has been done is a completely natural feeling for a performer. How else? Let’s say, “to myself” (“in my head”), I always hear music brighter and more interesting than it really comes out on the keyboard. It seems so to me, at least… And you constantly suffer from this.”

Well, it supports, inspires, gives new strength communication with the outstanding masters of pianism of our time. Communication is purely creative – concerts, records, video cassettes. It’s not that she takes an example from someone in her performance; this question itself – to take an example – in relation to it is not very suitable. Just contact with the art of major artists usually gives her deep joy, gives her spiritual food, as she puts it. Virsaladze speaks respectfully of K. Arrau; she was particularly impressed by the recording of the concert given by the Chilean pianist to mark his 80th birthday, which featured, among other things, Beethoven’s Aurora. Much admires Eliso Konstantinovna in the stage work of Annie Fischer. She likes, in a purely musical perspective, the game of A. Brendle. Of course, it is impossible not to mention the name of V. Horowitz – his Moscow tour in 1986 belongs to the bright and strong impressions in her life.

… Once a pianist said: “The longer I play the piano, the closer I get to know this instrument, the more its truly inexhaustible possibilities open up before me. How much more can and should be done here … ”She is constantly moving forward – this is the main thing; many of those who once were on a par with her, today are already noticeably lagging behind … As in an artist, there is an unceasing, everyday, exhausting struggle for perfection in her. For she is well aware that it is precisely in her profession, in the art of performing music on the stage, unlike in a number of other creative professions, that one cannot create eternal values. In this art, in the exact words of Stefan Zweig, “from performance to performance, from hour to hour, perfection must be won again and again … art is an eternal war, there is no end to it, there is one continuous beginning” (Zweig S. Selected works in two volumes. – M., 1956. T. 2. S. 579.).

G. Tsypin, 1990

“I pay tribute to her idea and her outstanding musicality. This is an artist of great scale, perhaps the strongest female pianist now … She is a very honest musician, and at the same time she has real modesty. (Svyatoslav Richter)

Eliso Virsaladze was born in Tbilisi. She studied the art of piano playing with her grandmother Anastasia Virsaladze (Lev Vlasenko and Dmitry Bashkirov also started in her class), a well-known pianist and teacher, an elder of the Georgian piano school, a student of Anna Esipova (Sergey Prokofiev’s mentor). She attended her class at the Paliashvili Special Music School (1950-1960), and under her guidance she graduated from the Tbilisi Conservatory (1960-1966). In 1966-1968 she studied at the postgraduate course of the Moscow Conservatory, where her teacher was Yakov Zak. “I loved to do everything myself – right or wrong, but on my own … Probably, this is in my character,” says the pianist. “And of course, I was lucky with teachers: I never knew what pedagogical dictatorship was.” She gave her first solo concert as a 10th grade student; the program includes two sonatas by Mozart, an intermezzo by Brahms, Schumann’s Eighth Novelette, Polka Rachmaninov. “In my work with my granddaughter,” wrote Anastasia Virsaladze, “I decided not to resort to etudes at all, except for the etudes of Chopin and Liszt, but I selected the appropriate repertoire … and paid special attention to Mozart’s compositions, which allow me to polish my mastery to the utmost.”

Laureate of the VII World Festival of Youth and Students in Vienna (1959, 2nd prize, silver medal), the All-Union Competition of Performing Musicians in Moscow (1961, 3rd prize), the II International Tchaikovsky Competition in Moscow (1962, 3rd prize, bronze medal), IV International Competition named after Schumann in Zwickau (1966, 1 prize, gold medal), Schumann Prize (1976). “Eliso Virsaladze left a wonderful impression,” said Yakov Flier about her performance at the Tchaikovsky Competition. – Her playing is surprisingly harmonious, real poetry is felt in it. The pianist perfectly understands the style of the pieces she performs, conveys their content with great freedom, confidence, ease, real artistic taste.”

Since 1959 – soloist of the Tbilisi, since 1977 – the Moscow Philharmonic. Since 1967 he has been teaching at the Moscow Conservatory, first as an assistant to Lev Oborin (until 1970), then to Yakov Zak (1970-1971). Since 1971 he has been teaching his own class, since 1977 he has been an assistant professor, since 1993 he has been a professor. Professor at the Higher School of Music and Theater in Munich (1995-2011). Since 2010 – professor at the Fiesole School of Music (Scuola di Musica di Fiesole) in Italy. Gives master classes in many countries of the world. Among her students are laureates of international competitions Boris Berezovsky, Ekaterina Voskresenskaya, Yakov Katsnelson, Alexei Volodin, Dmitry Kaprin, Marina Kolomiytseva, Alexander Osminin, Stanislav Khegay, Mamikon Nakhapetov, Tatyana Chernichka, Dinara Clinton, Sergei Voronov, Ekaterina Richter and others.

Since 1975, Virsaladze has been a jury member of numerous international competitions, among them the Tchaikovsky, Queen Elizabeth (Brussels), Busoni (Bolzano), Geza Anda (Zurich), Viana da Mota (Lisbon), Rubinstein (Tel Aviv), Schumann ( Zwickau), Richter (Moscow) and others. At the XII Tchaikovsky Competition (2002), Virsaladze refused to sign the jury protocol, disagreeing with the majority opinion.

Performs with the world’s largest orchestras in Europe, USA, Japan; worked with such conductors as Rudolf Barshai, Lev Marquis, Kirill Kondrashin, Gennady Rozhdestvensky, Evgeny Svetlanov, Yuri Temirkanov, Riccardo Muti, Kurt Sanderling, Dmitry Kitaenko, Wolfgang Sawallisch, Kurt Masur, Alexander Rudin and others. She performed in ensembles with Svyatoslav Richter , Oleg Kagan, Eduard Brunner, Viktor Tretyakov, the Borodin Quartet and other outstanding musicians. A particularly long and close artistic partnership links Virsaladze with Natalia Gutman; their duet is one of the long-lived chamber ensembles of the Moscow Philharmonic.

The art of Virsaladze was highly appreciated by Alexander Goldenweiser, Heinrich Neuhaus, Yakov Zak, Maria Grinberg, Svyatoslav Richter. At the invitation of Richter, the pianist took part in the international festivals Musical Festivities in Touraine and December Evenings. Virsaladze is a permanent participant of the festival in Kreuth (since 1990) and the Moscow International Festival “Dedication to Oleg Kagan” (since 2000). She founded the Telavi International Chamber Music Festival (held annually in 1984-1988, resumed in 2010). In September 2015, under her artistic direction, the chamber music festival “Eliso Virsaladze Presents” was held in Kurgan.

For a number of years, her students took part in the philharmonic concerts of the season ticket “Evenings with Eliso Virsaladze” at the BZK. Among the monograph programs of the last decade played by students and graduate students of her class are works by Mozart in transcriptions for 2 pianos (2006), all Beethoven sonatas (a cycle of 4 concertos, 2007/2008), all etudes (2010) and Liszt’s Hungarian rhapsodies (2011 ), Prokofiev’s piano sonatas (2012), etc. Since 2009, Virsaladze and students of her class have been participating in subscription chamber music concerts held at the Moscow Conservatory (project by professors Natalia Gutman, Eliso Virsaladze and Irina Kandinsky).

“By teaching, I get a lot, and there is a purely selfish interest in this. Starting with the fact that pianists have a gigantic repertoire. And sometimes I instruct a student to learn a piece that I would like to play myself, but do not have time for it. And so it turns out that I willy-nilly study it. What else? You are growing something. Thanks to your participation, what is inherent in your student comes out – this is very pleasant. And this is not only musical development, but also human development.

Virsaladze’s first recordings were made at the Melodiya company – works by Schumann, Chopin, Liszt, a number of piano concertos by Mozart. Her CD is included by the BMG label in the Russian Piano School series. The largest number of her solo and ensemble recordings were released by Live Classics, including works by Mozart, Schubert, Brahms, Prokofiev, Shostakovich, as well as all Beethoven cello sonatas recorded in an ensemble with Natalia Gutman: this is still one of the duet’s crown programs , regularly performed all over the world (including last year – in the best halls of Prague, Rome and Berlin). Like Gutman, Virsaladze is represented in the world by the Augstein Artist Management agency.

Virsaladze’s repertoire includes works by Western European composers of the XNUMXth-XNUMXth centuries. (Bach, Mozart, Haydn, Beethoven, Schubert, Schumann, Liszt, Chopin, Brahms), works by Tchaikovsky, Scriabin, Rachmaninov, Ravel, Prokofiev and Shostakovich. Virsaladze is cautious about contemporary music; Nevertheless, she took part in the performance of Schnittke’s Piano Quintet, Mansuryan’s Piano Trio, Taktakishvili’s Cello Sonata, and a number of other works by composers of our time. “In life, it so happens that I play the music of some composers more than others,” she says. – In recent years, my concert and teaching life has been so busy that you often cannot concentrate on one composer for a long time. I enthusiastically play almost all the authors of the XNUMXth and the first half of the XNUMXth century. I think that the composers who composed at that time had practically exhausted the possibilities of the piano as a musical instrument. In addition, they were all unsurpassed performers in their own way.

People’s Artist of the Georgian SSR (1971). People’s Artist of the USSR (1989). Laureate of the State Prize of the Georgian SSR named after Shota Rustaveli (1983), State Prize of the Russian Federation (2000). Cavalier of the Order of Merit for the Fatherland, IV degree (2007).

“Is it possible to wish a better Schumann after the Schumann played by Virsaladze today? I don’t think I’ve heard such a Schumann since Neuhaus. Today’s Klavierabend was a real revelation – Virsaladze began to play even better… Her technique is perfect and amazing. She sets scales for pianists.” (Svyatoslav Richter)