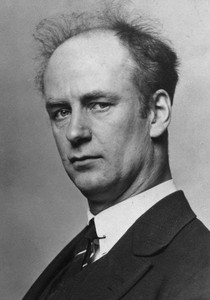

Daniel Barenboim |

Daniel Barenboim

Now it often happens that a well-known instrumentalist or singer, seeking to expand his range, turns to conducting, making it his second profession. But there are few cases when a musician from a young age manifests himself simultaneously in several areas. One exception is Daniel Barenboim. “When I perform as a pianist,” he says, “I strive to see an orchestra in the piano, and when I stand at the console, the orchestra seems to me like a piano.” Indeed, it is difficult to say what he owes more of his meteoric rise and his current fame.

Naturally, the piano still existed before conducting. Parents, teachers themselves (immigrants from Russia), began to teach her son from the age of five in her native Buenos Aires, where he first appeared on the stage at the age of seven. And in 1952, Daniel already performed with the Mozarteum Orchestra in Salzburg, playing Bach’s Concerto in D minor. The boy was lucky: he was taken under guardianship by Edwin Fischer, who advised him to take up conducting along the way. Since 1956, the musician lived in London, regularly performed there as a pianist, made several tours, received prizes at the D. Viotti and A. Casella competitions in Italy. During this period, he took lessons from Igor Markovich, Josef Krips and Nadia Boulanger, but his father remained the only piano teacher for him for the rest of his life.

Already in the early 60s, somehow imperceptibly, but very quickly, Barenboim’s star began to rise on the musical horizon. He gives concerts both as a pianist and as a conductor, he records several excellent records, among which, of course, all five of Beethoven’s concertos and Fantasia for piano, choir and orchestra attracted the most attention. True, mainly because Otto Klemperer was behind the console. It was a great honor for the young pianist, and he did everything to cope with the responsible task. But still, in this recording, Klemperer’s personality, his monumental concepts dominate; the soloist, as noted by one of the critics, “made only pianistically clean needlework.” “It’s not entirely clear why Klemperer needed a piano in this recording,” another reviewer sneered.

In a word, the young musician was still far from creative maturity. Nevertheless, critics paid tribute not only to his brilliant technique, a real “pearl”, but also to the meaningfulness and expressiveness of phrasing, the significance of his ideas. His interpretation of Mozart, with its seriousness, evoked the art of Clara Haskil, and the masculinity of the game made him see an excellent Beethovenist in perspective. During that period (January-February 1965), Barenboim made a long, almost a month-long trip around the USSR, performed in Moscow, Leningrad, Vilnius, Yalta and other cities. He performed Beethoven’s Third and Fifth Concertos, Brahms’ First, major works by Beethoven, Schumann, Schubert, Brahms, and Chopin’s miniatures. But it so happened that this trip went almost unnoticed – then Barenboim was not yet surrounded by a halo of glory …

Then Barenboim’s pianistic career began to decline somewhat. For several years he almost did not play, giving most of his time to conducting, he led the English Chamber Orchestra. He managed the latter not only at the console, but also at the instrument, having performed, among other works, almost all Mozart’s concertos. Since the beginning of the 70s, conducting and playing the piano have occupied an approximately equal place in his activities. He performs at the console of the best orchestras in the world, for some time he leads the Paris Symphony Orchestra and, along with this, works a lot as a pianist. Now he has accumulated a huge repertoire, including all the concertos and sonatas of Mozart, Beethoven, Brahms, many works by Liszt, Mendelssohn, Chopin, Schumann. Let’s add that he was one of the first foreign performers of Prokofiev’s Ninth Sonata, he recorded Beethoven’s violin concerto in the author’s piano arrangement (he himself was conducting the orchestra).

Barenboim constantly performs as an ensemble player with Fischer-Dieskau, singer Baker, for several years he played with his wife, cellist Jacqueline Dupré (who has now left the stage due to illness), as well as in a trio with her and violinist P. Zuckerman. A notable event in the concert life of London was the cycle of historical concerts “Masterpieces of Piano Music” given by him from Mozart to Liszt (season 1979/80). All this again and again confirms the high reputation of the artist. But at the same time, there is still a feeling of some kind of dissatisfaction, of unused opportunities. He plays like a good musician and an excellent pianist, he thinks “like a conductor at the piano”, but his playing still lacks the airiness, the persuasive power necessary for a great soloist, of course, if you approach it with the yardstick that the phenomenal talent of this musician suggests. It seems that even today his talent promises music lovers more than it gives them, at least in the field of pianism. Perhaps this assumption was only reinforced by new arguments after the artist’s recent tour in the USSR, both with solo programs and at the head of the Paris Orchestra.

Grigoriev L., Platek Ya., 1990