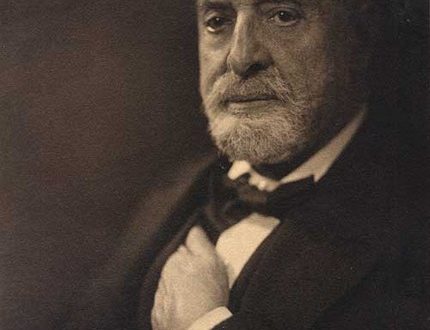

Charles Auguste de Bériot |

Charles Auguste de Beriot

Until recently, the Berio Violin School was perhaps the most common textbook for beginner violinists, and occasionally it is used by some teachers even today. Until now, students of music schools play fantasies, variations, Berio concertos. Melodious and melodious and “violin” written, they are the most grateful pedagogical material. Berio was not a great performer, but he was a great teacher, far ahead of his time in his views on music teaching. Not without reason among his students are such violinists as Henri Vietan, Joseph Walter, Johann Christian Lauterbach, Jesus Monasterio. Vietang idolized his teacher all his life.

But not only the results of his personal pedagogical activity are discussed. Berio is rightfully considered the head of the Belgian violin school of the XNUMXth century, which gave the world such famous performers as Artaud, Guis, Vietanne, Leonard, Emile Servais, Eugene Ysaye.

Berio came from an old noble family. He was born in Leuven on February 20, 1802 and lost both parents in early childhood. Fortunately, his extraordinary musical abilities attracted the attention of others. Music teacher Tibi took part in the initial training of little Charles. Berio studied very diligently and at the age of 9 he made his first public appearance, playing one of Viotti’s concertos.

The spiritual development of Berio was greatly influenced by the theories of the professor of French language and literature, the learned humanist Jacotot, who developed a “universal” pedagogical method based on the principles of self-education and spiritual self-organization. Fascinated by his method, Berio studied independently until the age of 19. At the beginning of 1821, he went to Paris to Viotti, who at that time served as director of the Grand Opera. Viotti treated the young violinist favorably and, on his recommendation, Berio began to attend classes in the class of Bayo, the most prominent professor at the Paris Conservatory at that time. The young man did not miss a single lesson of Bayo, carefully studied the methods of his teaching, testing them on himself. After Bayo, he studied for some time with the Belgian Andre Robberecht, and this was the end of his education.

The very first performance of Berio in Paris brought him wide popularity. His original, soft, lyrical game was very popular with the public, being in tune with the new sentimentalist-romantic moods that powerfully gripped the Parisians after the formidable years of the revolution and the Napoleonic wars. Success in Paris led to the fact that Berio received an invitation to England. The tour was a huge success. Upon his return to his homeland, the king of the Netherlands appointed Berio court soloist-violinist with an impressive salary of 2000 florins a year.

The revolution of 1830 put an end to his court service and he returned to his former position as a concert violinist. Shortly before, in 1829. Berio came to Paris to show his young pupil – Henri Vietana. Here, in one of the Parisian salons, he met his future wife, the famous opera singer Maria Malibran-Garcia.

Their love story is sad. The eldest daughter of the famous tenor Garcia, Maria was born in Paris in 1808. Brilliantly gifted, she learned composition and piano from Herold as a child, was fluent in four languages, and learned to sing from her father. In 1824, she made her debut in London, where she performed in a concert and, having learned the part of Rosina in Rossini’s Barber of Seville in 2 days, replaced the ill Pasta. In 1826, against her father’s wishes, she married the French merchant Malibran. The marriage turned out to be unhappy and the young woman, leaving her husband, went to Paris, where in 1828 she reached the position of the first soloist of the Grand Opera. In one of the Parisian salons, she met Berio. The young, graceful Belgian made an irresistible impression on the temperamental Spaniard. With her characteristic expansiveness, she confessed her love to him. But their romance gave rise to endless gossip, condemnation of the “higher” world. After leaving Paris, they went to Italy.

Their lives were spent in continuous concert trips. In 1833 they had a son, Charles Wilfred Berio, later a prominent pianist and composer. For several years, Malibran has been persistently seeking a divorce from her husband. However, she manages to free herself from marriage only in 1836, that is, after 6 painful years for her in the position of a mistress. Immediately after the divorce, her wedding to Berio took place in Paris, where only Lablache and Thalberg were present.

Maria was happy. She signed with delight with her new name. However, fate was not merciful to the Berio couple here either. Maria, who was fond of horseback riding, fell off her horse during one of the walks and received a strong blow to the head. She hid the incident from her husband, did not undertake treatment, and the disease, rapidly developing, led her to death. She died when she was only 28 years old! Shaken by the death of his wife, Berio was in a state of extreme mental depression until 1840. He almost stopped giving concerts and withdrew into himself. In fact, he never fully recovered from the blow.

In 1840 he made a great tour of Germany and Austria. In Berlin, he met and played music with the famous Russian amateur violinist A.F. Lvov. When he returned to his homeland, he was invited to take the post of professor at the Brussels Conservatory. Berio readily agreed.

In the early 50s, a new misfortune fell on him – a progressive eye disease. In 1852, he was forced to retire from work. 10 years before his death, Berio became completely blind. In October 1859, already half-blind, he came to St. Petersburg to Prince Nikolai Borisovich Yusupov (1827-1891). Yusupov – a violinist and an enlightened music lover, a student of Vieuxtan – invited him to take the place of the main leader of the home chapel. In the service of Prince Berio stayed from October 1859 to May 1860.

After Russia, Berio lived mainly in Brussels, where he died on April 10, 1870.

The performance and creativity of Berio was firmly fused with the traditions of the French classical violin school of Viotti – Baio. But he gave these traditions a sentimentalist-romantic character. In terms of talent, Berio was equally alien to the stormy romanticism of Paganini and the “profound” romanticism of Spohr. Berio’s lyrics are characterized by soft elegiacness and sensitivity, and fast-paced pieces – refinement and grace. The texture of his works is distinguished by its transparent lightness, lacy, filigree figuration. In general, his music has a touch of salonism and lacks depth.

We find a murderous assessment of his music in V. Odoevsky: “What is the variation of Mr. Berio, Mr. Kallivoda and tutti quanti? “A few years ago in France, a machine was invented, called the componuum, which itself composed variations on any theme. Today’s gentlemen writers imitate this machine. First you hear an introduction, a kind of recitative; then the motif, then the triplets, then the doubly connected notes, then the inevitable staccato with the inevitable pizzicato, then the adagio, and finally, for the supposed pleasure of the public – dancing and always the same everywhere!

One can join in the figurative characterization of Berio’s style, which Vsevolod Cheshikhin once gave to his Seventh Concerto: “The Seventh Concerto. not distinguished by special depth, a little sentimental, but very elegant and very effective. Berio’s muse … rather resembles Cecilia Carlo Dolce, the most beloved painting of the Dresden Gallery by women, this muse with an interesting pallor of a modern sentimentalist, an elegant, nervous brunette with thin fingers and coquettishly lowered eyes.

As a composer, Berio was very prolific. He wrote 10 violin concertos, 12 arias with variations, 6 notebooks of violin studies, many salon pieces, 49 brilliant concert duets for piano and violin, most of which were composed in collaboration with the most famous pianists – Hertz, Thalberg, Osborne, Benedict, Wolf. It was a kind of concert genre based on virtuoso-type variations.

Berio has compositions on Russian themes, for example, Fantasia for A. Dargomyzhsky’s song “Darling Maiden” Op. 115, dedicated to the Russian violinist I. Semenov. To the above, we must add the Violin School in 3 parts with the appendix “Transcendental School” (Ecole transendante du violon), composed of 60 etudes. Berio’s school reveals important aspects of his pedagogy. It shows the importance he attached to the musical development of the student. As an effective method of development, the author suggested solfegging – singing songs by ear. “The difficulties that the study of the violin presents at the beginning,” he wrote, “are reduced in part for a student who has completed a course of solfeggio. Without any difficulty in reading music, he can focus exclusively on his instrument and control the movements of his fingers and bow without much effort.

According to Berio, solfegging, in addition, helps the work by the fact that a person begins to hear what the eye sees, and the eye begins to see what the ear hears. By reproducing the melody with his voice and writing it down, the student sharpens his memory, makes him retain all the shades of the melody, its accents and color. Of course, the Berio School is outdated. The sprouts of the auditory teaching method, which is a progressive method of modern musical pedagogy, are valuable in it.

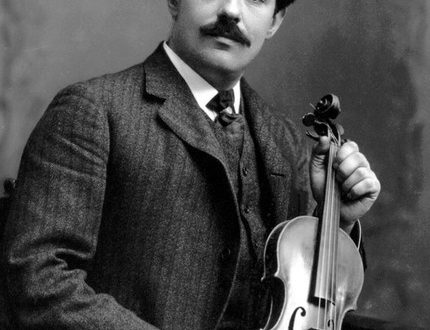

Berio had a small, but full of inexplicable beauty sound. It was a lyricist, a violin poet. Heine wrote in a letter from Paris in 1841: “Sometimes I can’t get rid of the idea that the soul of his late wife is in Berio’s violin and she sings. Only Ernst, a poetic Bohemian, can extract such tender, sweetly suffering sounds from his instrument.

L. Raaben