Arcangelo Corelli (Arcangelo Corelli) |

Arcangelo Corelli

The work of the outstanding Italian composer and violinist A. Corelli had a huge impact on European instrumental music of the late XNUMXth – first half of the XNUMXth centuries, he is rightfully considered the founder of the Italian violin school. Many of the major composers of the following era, including J. S. Bach and G. F. Handel, highly valued Corelli’s instrumental compositions. He showed himself not only as a composer and a wonderful violinist, but also as a teacher (the Corelli school has a whole galaxy of brilliant masters) and a conductor (he was the leader of various instrumental ensembles). Creativity Corelli and his diverse activities have opened a new page in the history of music and musical genres.

Little is known about Corelli’s early life. He received his first music lessons from a priest. After changing several teachers, Corelli finally ends up in Bologna. This city was the birthplace of a number of remarkable Italian composers, and the stay there had, apparently, a decisive influence on the future fate of the young musician. In Bologna, Corelli studies under the guidance of the famous teacher J. Benvenuti. The fact that already in his youth Corelli achieved outstanding success in the field of violin playing is evidenced by the fact that in 1670, at the age of 17, he was admitted to the famous Bologna Academy. In the 1670s Corelli moves to Rome. Here he plays in various orchestral and chamber ensembles, directs some ensembles, and becomes a church bandmaster. It is known from Corelli’s letters that in 1679 he entered the service of Queen Christina of Sweden. As an orchestra musician, he is also involved in composition – composing sonatas for his patroness. Corelli’s first work (12 church trio sonatas) appeared in 1681. In the mid-1680s. Corelli entered the service of the Roman Cardinal P. Ottoboni, where he remained until the end of his life. After 1708, he retired from public speaking and concentrated all his energies on creativity.

Corelli’s compositions are relatively few in number: in 1685, following the first opus, his chamber trio sonatas op. 2, in 1689 – 12 church trio sonatas op. 3, in 1694 – chamber trio sonatas op. 4, in 1700 – chamber trio sonatas op. 5. Finally, in 1714, after Corelli’s death, his concerti grossi op. was published in Amsterdam. 6. These collections, as well as several individual plays, constitute the legacy of Corelli. His compositions are intended for bowed string instruments (violin, viola da gamba) with the harpsichord or organ as accompanying instruments.

Creativity Corelli includes 2 main genres: sonatas and concertos. It was in Corelli’s work that the sonata genre was formed in the form in which it is characteristic of the preclassical era. Corelli’s sonatas are divided into 2 groups: church and chamber. They differ both in the composition of the performers (the organ accompanies in the church sonata, the harpsichord in the chamber sonata), and in content (the church sonata is distinguished by its strictness and depth of content, the chamber one is close to the dance suite). The instrumental composition for which such sonatas were composed included 2 melodic voices (2 violins) and accompaniment (organ, harpsichord, viola da gamba). That is why they are called trio sonatas.

Corelli’s concertos also became an outstanding phenomenon in this genre. The concerto grosso genre existed long before Corelli. He was one of the forerunners of symphonic music. The idea of the genre was a kind of competition between a group of solo instruments (in Corelli’s concertos this role is played by 2 violins and a cello) with an orchestra: the concerto was thus built as an alternation of solo and tutti. Corelli’s 12 concertos, written in the last years of the composer’s life, became one of the brightest pages in the instrumental music of the early XNUMXth century. They are still perhaps the most popular work of Corelli.

A. Pilgun

The violin is a musical instrument of national origin. She was born around the XNUMXth century and for a long time existed only among the people. “The widespread use of the violin in folk life is vividly illustrated by numerous paintings and engravings of the XNUMXth century. Their plots are: violin and cello in the hands of wandering musicians, rural violinists, amusing people at fairs and squares, at festivities and dances, in taverns and taverns. The violin even evoked a contemptuous attitude towards it: “You meet few people who use it, except for those who live by their labor. It is used for dancing at weddings, masquerades,” wrote Philibert Iron Leg, a French musician and scientist in the first half of the XNUMXth century.

A disdainful view of the violin as a rough common folk instrument is reflected in numerous sayings and idioms. In French, the word violon (violin) is still used as a curse, the name of a useless, stupid person; in English, the violin is called fiddle, and the folk violinist is called fiddler; at the same time, these expressions have a vulgar meaning: the verb fiddlefaddle means – to talk in vain, to chatter; fiddlingmann translates as a thief.

In folk art, there were great craftsmen among the wandering musicians, but history did not preserve their names. The first violinist known to us was Battista Giacomelli. He lived in the second half of the XNUMXth century and enjoyed extraordinary fame. Contemporaries simply called him il violino.

Large violin schools arose in the XNUMXth century in Italy. They were formed gradually and were associated with the two musical centers of this country – Venice and Bologna.

Venice, a trading republic, has long lived a noisy city life. There were open theatres. Colorful carnivals were organized on the squares with the participation of ordinary people, itinerant musicians demonstrated their art and were often invited to patrician houses. The violin began to be noticed and even preferred to other instruments. It sounded excellent in theater rooms, as well as at national holidays; it favorably differed from the sweet but quiet viola by the richness, beauty and fullness of the timbre, it sounded good solo and in the orchestra.

The Venetian school took shape in the second decade of the 1629th century. In the work of its head, Biagio Marini, the foundations of the solo violin sonata genre were laid. Representatives of the Venetian school were close to folk art, willingly used in their compositions the techniques of playing folk violinists. So, Biagio Marini wrote (XNUMX) “Ritornello quinto” for two violins and a quitaron (i.e. bass lute), reminiscent of folk dance music, and Carlo Farina in “Capriccio Stravagante” applied various onomatopoeic effects, borrowing them from the practice of wandering musicians . In Capriccio, the violin imitates the barking of dogs, the meowing of cats, the cry of a rooster, the cackling of a chicken, the whistling of marching soldiers, etc.

Bologna was the spiritual center of Italy, the center of science and art, the city of academies. In Bologna of the XNUMXth century, the influence of the ideas of humanism was still felt, the traditions of the late Renaissance lived on, therefore the violin school formed here was noticeably different from the Venetian one. The Bolognese sought to give vocal expressiveness to instrumental music, since the human voice was considered the highest criterion. The violin had to sing, it was likened to a soprano, and even its registers were limited to three positions, that is, the range of a high female voice.

The Bologna violin school included many outstanding violinists – D. Torelli, J.-B. Bassani, J.-B. Vitali. Their work and skill prepared that strict, noble, sublimely pathetic style, which found its highest expression in the work of Arcangelo Corelli.

Corelli… Which of the violinists does not know this name! Young pupils of music schools and colleges study his sonatas, and his Concerti grossi are performed in the halls of the philharmonic society by famous masters. In 1953, the whole world celebrated the 300th anniversary of the birth of Corelli, linking his work with the greatest conquests of Italian art. And indeed, when you think about him, you involuntarily compare the pure and noble music he created with the art of sculptors, architects and painters of the Renaissance. With the wise simplicity of church sonatas, it resembles the paintings of Leonardo da Vinci, and with the bright, heartfelt lyrics and harmony of chamber sonatas, it resembles Raphael.

During his lifetime, Corelli enjoyed worldwide fame. Kuperin, Handel, J.-S. bowed before him. Bach; generations of violinists studied on his sonatas. For Handel, his sonatas became a model of his own work; Bach borrowed from him the themes for fugues and owed much to him in the melodiousness of the violin style of his works.

Corelli was born on February 17, 1653 in the small town of Romagna Fusignano, located halfway between Ravenna and Bologna. His parents belonged to the number of educated and wealthy residents of the town. Among Corelli’s ancestors there were many priests, doctors, scientists, lawyers, poets, but not a single musician!

Corelli’s father died a month before Arcangelo’s birth; along with four older brothers, he was raised by his mother. When the son began to grow up, his mother brought him to Faenza so that the local priest would give him his first music lessons. Classes continued in Lugo, then in Bologna, where Corelli ended up in 1666.

Biographical information about this time of his life is very scarce. It is only known that in Bologna he studied with the violinist Giovanni Benvenuti.

The years of Corelli’s apprenticeship coincided with the heyday of the Bolognese violin school. Its founder, Ercole Gaibara, was the teacher of Giovanni Benvenuti and Leonardo Brugnoli, whose high skill could not but have a strong influence on the young musician. Arcangelo Corelli was a contemporary of such brilliant representatives of the Bolognese violin art as Giuseppe Torelli, Giovanni Battista Bassani (1657-1716) and Giovanni Battista Vitali (1644-1692) and others.

Bologna was famous not only for violinists. At the same time, Domenico Gabrielli laid the foundations of cello solo music. There were four academies in the city – musical concert societies that attracted professionals and amateurs to their meetings. In one of them – the Philharmonic Academy, founded in 1650, Corelli was admitted at the age of 17 as a full member.

Where Corelli lived from 1670 to 1675 is unclear. His biographies are contradictory. J.-J. Rousseau reports that in 1673 Corelli visited Paris and that there he had a major clash with Lully. The biographer Pencherle refutes Rousseau, arguing that Corelli has never been to Paris. Padre Martini, one of the most famous musicians of the XNUMXth century, suggests that Corelli spent these years in Fusignano, “but decided, in order to satisfy his ardent desire and, yielding to the insistence of numerous dear friends, to go to Rome, where he studied under the guidance of the famous Pietro Simonelli, with having accepted the rules of counterpoint with great ease, thanks to which he became an excellent and complete composer.

Corelli moved to Rome in 1675. The situation there was very difficult. At the turn of the XNUMXth-XNUMXth centuries, Italy was going through a period of fierce internecine wars and was losing its former political significance. Interventionist expansion from Austria, France, and Spain was added to the internal civil strife. National fragmentation, continuous wars caused a reduction in trade, economic stagnation, and the impoverishment of the country. In many areas, feudal orders were restored, the people groaned from unbearable requisitions.

The clerical reaction was added to the feudal reaction. Catholicism sought to regain its former power of influence on the minds. With particular intensity, social contradictions manifested themselves precisely in Rome, the center of Catholicism. However, in the capital there were wonderful opera and drama theatres, literary and musical circles and salons. True, the clerical authorities oppressed them. In 1697, by order of Pope Innocent XII, the largest opera house in Rome, Tor di Nona, was closed as “immoral”.

The efforts of the church to prevent the development of secular culture did not lead to the desired results for it – the musical life only began to concentrate in the homes of patrons. And among the clergy one could meet educated people who were distinguished by a humanistic worldview and by no means shared the restrictive tendencies of the church. Two of them – Cardinals Panfili and Ottoboni – played a prominent role in the life of Corelli.

In Rome, Corelli quickly gained a high and strong position. Initially, he worked as the second violinist in the orchestra of the theater Tor di Nona, then the third of four violinists in the ensemble of the French Church of St. Louis. However, he did not last long in the position of second violinist. On January 6, 1679, at the Capranica Theater, he conducted the work of his friend the composer Bernardo Pasquini “Dove e amore e pieta”. At this time, he is already being evaluated as a wonderful, unsurpassed violinist. The words of the abbot F. Raguenay can serve as evidence of what has been said: “I saw in Rome,” the abbot wrote, “in the same opera, Corelli, Pasquini and Gaetano, who, of course, have the best violin, harpsichord and theorbo in the world.”

It is possible that from 1679 to 1681 Corelli was in Germany. This assumption is expressed by M. Pencherl, based on the fact that in these years Corelli was not listed as an employee of the orchestra of the church of St.. Louis. Various sources mention that he was in Munich, worked for the Duke of Bavaria, visited Heidelberg and Hanover. However, Pencherl adds, none of this evidence has been proven.

In any case, since 1681, Corelli has been in Rome, often performing in one of the most brilliant salons of the Italian capital – the salon of the Swedish Queen Christina. “The Eternal City,” writes Pencherl, “at that time was overwhelmed by a wave of secular entertainment. Aristocratic houses competed with each other in terms of various festivities, comedy and opera performances, performances of virtuosos. Among such patrons as Prince Ruspoli, Constable of Columns, Rospigliosi, Cardinal Savelli, Duchess of Bracciano, Christina of Sweden stood out, who, despite her abdication, retained all her august influence. She was distinguished by originality, independence of character, liveliness of mind and intelligence; she was often referred to as the “Northern Pallas”.

Christina settled in Rome in 1659 and surrounded herself with artists, writers, scientists, artists. Possessing a huge fortune, she arranged grand celebrations in her Palazzo Riario. Most of Corelli’s biographies mention a holiday given by her in honor of the English ambassador who arrived in Rome in 1687 to negotiate with the pope on behalf of King James II, who sought to restore Catholicism in England. The celebration was attended by 100 singers and an orchestra of 150 instruments, led by Corelli. Corelli dedicated his first printed work, Twelve Church Trio Sonatas, published in 1681, to Christina of Sweden.

Corelli did not leave the orchestra of the church of St. Louis and ruled it at all church holidays until 1708. The turning point in his fate was July 9, 1687, when he was invited to the service of Cardinal Panfili, from whom in 1690 he transferred to the service of Cardinal Ottoboni. A Venetian, nephew of Pope Alexander VIII, Ottoboni was the most educated man of his era, a connoisseur of music and poetry, and a generous philanthropist. He wrote the opera “II Colombo obero l’India scoperta” (1691), and Alessandro Scarlatti created the opera “Statira” on his libretto.

“To tell you the truth,” Blainville wrote, “clerical vestments do not suit Cardinal Ottoboni very well, who has an exceptionally refined and gallant appearance and, apparently, is willing to exchange his clergy for a secular one. Ottoboni loves poetry, music and the society of learned people. Every 14 days he arranges meetings (academies) where prelates and scholars meet, and where Quintus Sectanus, a.k.a. Monsignor Segardi, plays a major role. His Holiness also maintains at his expense the best musicians and other artists, among whom is the famous Arcangelo Corelli.

The cardinal’s chapel numbered over 30 musicians; under the direction of Corelli, it has developed into a first-class ensemble. Demanding and sensitive, Arcangelo achieved exceptional accuracy of the game and unity of strokes, which was already completely unusual. “He would stop the orchestra as soon as he noticed a deviation in at least one bow,” recalled his student Geminiani. Contemporaries spoke of the Ottoboni orchestra as a “musical miracle”.

On April 26, 1706, Corelli was admitted to the Academy of Arcadia, founded in Rome in 1690 – to protect and glorify popular poetry and eloquence. Arcadia, which united princes and artists in a spiritual brotherhood, counted among its members Alessandro Scarlatti, Arcangelo Corelli, Bernardo Pasquini, Benedetto Marcello.

“A large orchestra played in Arcadia under the baton of Corelli, Pasquini or Scarlatti. It indulged in poetic and musical improvisations, which caused artistic competitions between poets and musicians.

Since 1710, Corelli stopped performing and was engaged only in composition, working on the creation of the “Concerti grossi”. At the end of 1712, he left the Ottoboni Palace and moved to his private apartment, where he kept his personal belongings, musical instruments and an extensive collection of paintings (136 paintings and drawings), containing paintings by Trevisani, Maratti, Brueghel, Poussin landscapes, Madonna Sassoferrato. Corelli was highly educated and was a great connoisseur of painting.

On January 5, 1713, he wrote a will, leaving a painting by Brueghel to Cardinal Colonne, one of the paintings of his choice to Cardinal Ottoboni, and all the instruments and manuscripts of his compositions to his beloved student Matteo Farnari. He did not forget to give a modest lifetime pension to his servants Pippo (Philippa Graziani) and his sister Olympia. Corelli died on the night of January 8, 1713. “His death saddened Rome and the world.” At the insistence of Ottoboni, Corelli is buried in the Pantheon of Santa Maria della Rotunda as one of the greatest musicians in Italy.

“Corelli the composer and Corelli the virtuoso are inseparable from each other,” writes the Soviet music historian K. Rosenshield. “Both confirmed the high classicism style in violin art, combining the deep vitality of music with the harmonious perfection of form, Italian emotionality with the complete dominance of a reasonable, logical beginning.”

In Soviet literature about Corelli, numerous connections of his work with folk melodies and dances are noted. In the gigues of chamber sonatas, the rhythms of folk dances can be heard, and the most famous of his solo violin works, Folia, is stuffed with the theme of a Spanish-Portuguese folk song that tells about unhappy love.

Another sphere of musical images crystallized with Corelli in the genre of church sonatas. These works of his are filled with majestic pathos, and the slender forms of fugue allegro anticipate the fugues of J.-S. Bach. Like Bach, Corelli narrates in sonatas about deeply human experiences. His humanistic worldview did not allow him to subordinate his work to religious motives.

Corelli was distinguished by exceptional demands on the music he composed. Although he began to study composition back in the 70s of the 6th century and worked intensively all his life, however, out of all that he wrote, he published only 1 cycles (opus 6-12), which made up the harmonious building of his creative heritage: 1681 church trio sonatas (12); 1685 chamber trio sonatas (12); 1689 church trio sonatas (12); 1694 chamber trio sonatas (6); a collection of sonatas for violin solo with bass – 6 church and 1700 chamber (12) and 6 Grand Concertos (concerto grosso) – 6 church and 1712 chamber (XNUMX).

When artistic ideas demanded it, Corelli did not stop at breaking the canonized rules. The second collection of his trio sonatas caused controversy among Bolognese musicians. Many of them protested against the “forbidden” parallel fifths used there. In response to a bewildered letter addressed to him, whether he did it deliberately, Corelli answered caustically and accused his opponents of not knowing the elementary rules of harmony: “I don’t see how great their knowledge of compositions and modulations is, because if they were moved in art and understood its subtleties and depths, they would know what harmony is and how it can enchant, elevate the human spirit, and they would not be so petty – a quality that is usually generated by ignorance.

The style of Corelli’s sonatas now seems restrained and strict. However, during the life of the composer, his works were perceived differently. Italian sonatas “Amazing! feelings, imagination and soul, – Raguenay wrote in the cited work, – the violinists who perform them are subject to their gripping frenzied power; they torment their violins. as if possessed.”

Judging by most of the biography, Corelli had a balanced character, which also manifested itself in the game. However, Hawkins in The History of Music writes: “A man who saw him play claimed that during the performance his eyes became filled with blood, became fiery red, and the pupils revolved as if in agony.” It is difficult to believe such a “colorful” description, but perhaps there is a grain of truth in it.

Hawkins relates that once in Rome, Corelli was unable to play a passage in Handel’s Concerto grosso. “Handel tried in vain to explain to Corelli, the leader of the orchestra, how to perform and, finally, losing patience, snatched the violin from his hands and played it himself. Then Corelli answered him in the most polite way: “But, dear Saxon, this is music of the French style, in which I am not versed.” In fact, the overture “Trionfo del tempo” was played, written in the style of Corelli’s concerto grosso, with two solo violins. Truly Handelian in power, it was alien to the calm, graceful manner of Corelli’s playing “and he did not manage to” attack “with sufficient power these rumbling passages.”

Pencherl describes another similar case with Corelli, which can only be understood by remembering some of the features of the Bolognese violin school. As mentioned, the Bolognese, including Corelli, limited the range of the violin to three positions and did so deliberately out of a desire to bring the instrument closer to the sound of the human voice. As a result of this, Corelli, the greatest performer of his era, owned the violin only within three positions. Once he was invited to Naples, to the court of the king. At the concert, he was offered to play the violin part in Alessandro Scarlatti’s opera, which contained a passage with high positions, and Corelli was unable to play. In confusion, he began the next aria instead of C minor in C major. “Let’s do it again,” said Scarlatti. Corelli began again in a major, and the composer interrupted him again. “Poor Corelli was so embarrassed that he preferred to quietly return to Rome.”

Corelli was very modest in his personal life. The only wealth of his dwelling was a collection of paintings and tools, but the furnishings consisted of an armchair and stools, four tables, of which one was alabaster in oriental style, a simple bed without a canopy, an altar with a crucifix and two chests of drawers. Handel reports that Corelli usually dressed in black, wore a dark coat, always walked and protested if he was offered a carriage.

Corelli’s life, in general, turned out well. He was recognized, enjoyed honor and respect. Even being in the service of patrons, he did not drink the bitter cup, which, for example, went to Mozart. Both Panfili and Ottoboni turned out to be people who highly appreciated the extraordinary artist. Ottoboni was a great friend of Corelli and his entire family. Pencherle quotes the letters of the cardinal to the legate of Ferrara, in which he begged for assistance to the Arcangelo brothers, who belong to a family whom he loves with ardent and special tenderness. Surrounded by sympathy and admiration, financially secure, Corelli could calmly devote himself to creativity for most of his life.

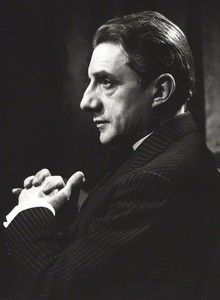

Very little can be said about Corelli’s pedagogy, and yet he was obviously an excellent educator. Remarkable violinists studied under him, who in the first half of the 1697th century made the glory of the violin art of Italy – Pietro Locatelli, Francisco Geminiani, Giovanni Battista Somis. Around XNUMX, one of his eminent students, the English Lord Edinhomb, commissioned a portrait of Corelli from the artist Hugo Howard. This is the only existing image of the great violinist. The large features of his face are majestic and calm, courageous and proud. So he was in life, simple and proud, courageous and humane.

L. Raaben