Antonio Vivaldi |

Antonio Vivaldi

One of the largest representatives of the Baroque era, A. Vivaldi entered the history of musical culture as the creator of the genre of instrumental concerto, the founder of orchestral program music. Vivaldi’s childhood is connected with Venice, where his father worked as a violinist in the Cathedral of St. Mark. The family had 6 children, of which Antonio was the eldest. There are almost no details about the composer’s childhood years. It is only known that he studied playing the violin and harpsichord.

On September 18, 1693, Vivaldi was tonsured a monk, and on March 23, 1703, he was ordained a priest. At the same time, the young man continued to live at home (presumably due to a serious illness), which gave him the opportunity not to leave music lessons. For the color of his hair, Vivaldi was nicknamed the “red monk.” It is assumed that already in these years he was not too zealous about his duties as a clergyman. Many sources retell the story (perhaps unreliable, but revealing) about how one day during the service, the “red-haired monk” hastily left the altar to write down the theme of the fugue, which suddenly occurred to him. In any case, Vivaldi’s relations with clerical circles continued to heat up, and soon he, citing his poor health, publicly refused to celebrate mass.

In September 1703, Vivaldi began working as a teacher (maestro di violino) in the Venetian charitable orphanage “Pio Ospedale delia Pieta”. His duties included learning to play the violin and viola d’amore, as well as overseeing the preservation of stringed instruments and buying new violins. The “services” at the “Pieta” (they can rightly be called concerts) were in the center of attention of the enlightened Venetian public. For reasons of economy, in 1709 Vivaldi was fired, but in 1711-16. reinstated in the same position, and from May 1716 he was already concertmaster of the Pieta orchestra.

Even before the new appointment, Vivaldi established himself not only as a teacher, but also as a composer (mainly the author of sacred music). In parallel with his work at Pieta, Vivaldi is looking for opportunities to publish his secular writings. 12 trio sonatas op. 1 were published in 1706; in 1711 the most famous collection of violin concertos “Harmonic Inspiration” op. 3; in 1714 – another collection called “Extravagance” op. 4. Vivaldi’s violin concertos very soon became widely known in Western Europe and especially in Germany. Great interest in them was shown by I. Quantz, I. Mattheson, the Great J. S. Bach “for pleasure and instruction” personally arranged 9 violin concertos by Vivaldi for clavier and organ. In the same years, Vivaldi wrote his first operas Otto (1713), Orlando (1714), Nero (1715). In 1718-20. he lives in Mantua, where he mainly writes operas for the carnival season, as well as instrumental compositions for the Mantua ducal court.

In 1725, one of the composer’s most famous opuses came out of print, bearing the subtitle “The Experience of Harmony and Invention” (op. 8). Like the previous ones, the collection is made up of violin concertos (there are 12 of them here). The first 4 concerts of this opus are named by the composer, respectively, “Spring”, “Summer”, “Autumn” and “Winter”. In modern performing practice, they are often combined into the cycle “Seasons” (there is no such heading in the original). Apparently, Vivaldi was not satisfied with the income from the publication of his concertos, and in 1733 he told a certain English traveler E. Holdsworth about his intention to abandon further publications, since, unlike printed manuscripts, handwritten copies were more expensive. In fact, since then, no new original opuses by Vivaldi have appeared.

Late 20s – 30s. often referred to as “years of travel” (preferred to Vienna and Prague). In August 1735, Vivaldi returned to the post of bandmaster of the Pieta orchestra, but the governing committee did not like his subordinate’s passion for travel, and in 1738 the composer was fired. At the same time, Vivaldi continued to work hard in the genre of opera (one of his librettists was the famous C. Goldoni), while he preferred to personally participate in the production. However, Vivaldi’s opera performances were not particularly successful, especially after the composer was deprived of the opportunity to act as director of his operas at the Ferrara theater due to the cardinal’s ban on entering the city (the composer was accused of having a love affair with Anna Giraud, his former student, and refusing to “red-haired monk” to celebrate mass). As a result, the opera premiere in Ferrara failed.

In 1740, shortly before his death, Vivaldi went on his last trip to Vienna. The reasons for his sudden departure are unclear. He died in the house of the widow of a Viennese saddler by the name of Waller and was beggarly buried. Soon after his death, the name of the outstanding master was forgotten. Almost 200 years later, in the 20s. 300th century the Italian musicologist A. Gentili discovered a unique collection of the composer’s manuscripts (19 concertos, 1947 operas, spiritual and secular vocal compositions). From this time begins a genuine revival of the former glory of Vivaldi. In 700, the Ricordi music publishing house began to publish the complete works of the composer, and the Philips company recently began to implement an equally grandiose plan – the publication of “all” Vivaldi on record. In our country, Vivaldi is one of the most frequently performed and most beloved composers. The creative heritage of Vivaldi is great. According to the authoritative thematic-systematic catalog of Peter Ryom (international designation – RV), it covers more than 500 titles. The main place in the work of Vivaldi was occupied by an instrumental concerto (a total of about 230 preserved). The composer’s favorite instrument was the violin (about 60 concertos). In addition, he wrote concertos for two, three and four violins with orchestra and basso continue, concertos for viola d’amour, cello, mandolin, longitudinal and transverse flutes, oboe, bassoon. More than 40 concertos for string orchestra and basso continue, sonatas for various instruments are known. Of the more than XNUMX operas (the authorship of Vivaldi in respect of which has been established with certainty), the scores of only half of them have survived. Less popular (but no less interesting) are his numerous vocal compositions – cantatas, oratorios, works on spiritual texts (psalms, litanies, “Gloria”, etc.).

Many of Vivaldi’s instrumental compositions have programmatic subtitles. Some of them refer to the first performer (Carbonelli Concerto, RV 366), others to the festival during which this or that composition was first performed (On the Feast of St. Lorenzo, RV 286). A number of subtitles point to some unusual detail of the performing technique (in the concerto called “L’ottavina”, RV 763, all solo violins must be played in the upper octave). The most typical headings that characterize the prevailing mood are “Rest”, “Anxiety”, “Suspicion” or “Harmonic Inspiration”, “Zither” (the last two are the names of collections of violin concertos). At the same time, even in those works whose titles seem to indicate external pictorial moments (“Storm at Sea”, “Goldfinch”, “Hunting”, etc.), the main thing for the composer is always the transmission of the general lyrical mood. The score of The Four Seasons is provided with a relatively detailed program. Already during his lifetime, Vivaldi became famous as an outstanding connoisseur of the orchestra, the inventor of many coloristic effects, he did a lot to develop the technique of playing the violin.

S. Lebedev

The wonderful works of A. Vivaldi are of great, world-wide fame. Modern famous ensembles devote evenings to his work (the Moscow Chamber Orchestra conducted by R. Barshai, the Roman Virtuosos, etc.) and, perhaps, after Bach and Handel, Vivaldi is the most popular among composers of the musical baroque era. Today it seems to have received a second life.

He enjoyed wide popularity during his lifetime, was the creator of a solo instrumental concerto. The development of this genre in all countries during the entire preclassical period is associated with the work of Vivaldi. Vivaldi’s concertos served as a model for Bach, Locatelli, Tartini, Leclerc, Benda and others. Bach arranged 6 violin concertos by Vivaldi for the clavier, made organ concertos out of 2 and reworked one for 4 claviers.

“At the time when Bach was in Weimar, the entire musical world admired the originality of the concerts of the latter (i.e., Vivaldi. – L.R.). Bach transcribed the Vivaldi concertos not to make them accessible to the general public, and not to learn from them, but only because it gave him pleasure. Undoubtedly, he benefited from Vivaldi. He learned from him the clarity and harmony of construction. perfect violin technique based on melodiousness…”

However, being very popular during the first half of the XNUMXth century, Vivaldi was later almost forgotten. “While after the death of Corelli,” writes Pencherl, “the memory of him became more and more strengthened and embellished over the years, Vivaldi, who was almost less famous during his lifetime, literally disappeared after a few five years both materially and spiritually. His creations leave the programs, even the features of his appearance are erased from memory. About the place and date of his death, there were only guesses. For a long time, dictionaries repeat only meager information about him, filled with commonplaces and replete with errors ..».

Until recently, Vivaldi was only interested in historians. In music schools, at the initial stages of education, 1-2 of his concerts were studied. In the middle of the XNUMXth century, attention to his work increased rapidly, and interest in the facts of his biography increased. Yet we still know very little about him.

The ideas about his heritage, of which most of it remained in obscurity, were completely wrong. Only in 1927-1930, the Turin composer and researcher Alberto Gentili managed to discover about 300 (!) Vivaldi autographs, which were the property of the Durazzo family and were stored in their Genoese villa. Among these manuscripts are 19 operas, an oratorio and several volumes of church and instrumental works by Vivaldi. This collection was founded by Prince Giacomo Durazzo, a philanthropist, since 1764, the Austrian envoy in Venice, where, in addition to political activities, he was engaged in collecting art samples.

According to Vivaldi’s will, they were not subject to publication, but Gentili secured their transfer to the National Library and thereby made them public. The Austrian scientist Walter Kollender began to study them, arguing that Vivaldi was several decades ahead of the development of European music in the use of dynamics and purely technical methods of violin playing.

According to the latest data, it is known that Vivaldi wrote 39 operas, 23 cantatas, 23 symphonies, many church compositions, 43 arias, 73 sonatas (trio and solo), 40 concerti grossi; 447 solo concertos for various instruments: 221 for violin, 20 for cello, 6 for viol damour, 16 for flute, 11 for oboe, 38 for bassoon, concertos for mandolin, horn, trumpet and for mixed compositions: wooden with violin, for 2 -x violins and lutes, 2 flutes, oboe, English horn, 2 trumpets, violin, 2 violas, bow quartet, 2 cembalos, etc.

The exact birthday of Vivaldi is unknown. Pencherle gives only an approximate date – a little earlier than 1678. His father Giovanni Battista Vivaldi was a violinist in the ducal chapel of St. Mark in Venice, and a first-class performer. In all likelihood, the son received a violin education from his father, while he studied composition with Giovanni Legrenzi, who headed the Venetian violin school in the second half of the XNUMXth century, was an outstanding composer, especially in the field of orchestral music. Apparently from him Vivaldi inherited a passion for experimenting with instrumental compositions.

At a young age, Vivaldi entered the same chapel where his father worked as a leader, and later replaced him in this position.

However, a professional musical career was soon supplemented by a spiritual one – Vivaldi became a priest. This happened on September 18, 1693. Until 1696, he was in the junior spiritual rank, and received full priestly rights on March 23, 1703. “Red-haired pop” – derisively called Vivaldi in Venice, and this nickname remained with him throughout his life.

Having received the priesthood, Vivaldi did not stop his musical studies. In general, he was engaged in church service for a short time – only one year, after which he was forbidden to serve masses. Biographers give a funny explanation for this fact: “Once Vivaldi was serving Mass, and suddenly the theme of the fugue came to his mind; leaving the altar, he goes to the sacristy to write down this theme, and then returns to the altar. A denunciation followed, but the Inquisition, considering him a musician, that is, as if crazy, only limited himself to forbidding him to continue to serve mass.

Vivaldi denied such cases and explained the ban on church services by his painful condition. By 1737, when he was due to arrive in Ferrara to stage one of his operas, the papal nuncio Ruffo forbade him from entering the city, putting forward, among other reasons, that he did not serve Mass. Then Vivaldi sent a letter (November 16, 1737) to his patron, the Marquis Guido Bentivoglio: “For 25 years now I have not been serving Mass and will never serve it in the future, but not by prohibition, as may be reported to your grace, but due to my own decision, caused by an illness that has been oppressing me since the day I was born. When I was ordained a priest, I celebrated Mass for a year or a little, then I stopped doing it, forced to leave the altar three times, not finishing it due to illness. As a result, I almost always live at home and travel only in a carriage or gondola, because I cannot walk because of a chest disease, or rather chest tightness. Not a single nobleman calls me to his house, not even our prince, since everyone knows about my illness. After a meal, I can usually take a walk, but never on foot. That’s the reason why I don’t send Mass.” The letter is curious in that it contains some everyday details of Vivaldi’s life, which apparently proceeded in a closed way within the boundaries of his own home.

Forced to give up his church career, in September 1703 Vivaldi entered one of the Venetian conservatories, called the Musical Seminary of the Hospice House of Piety, for the position of “violin maestro”, with a content of 60 ducats a year. In those days, orphanages (hospitals) at churches were called conservatories. In Venice there were four for girls, in Naples four for boys.

The famous French traveler de Brosse left the following description of the Venetian conservatories: “The music of hospitals is excellent here. There are four of them, and they are filled with illegitimate girls, as well as orphans or those who are not able to raise their parents. They are brought up at the expense of the state and they are taught mainly music. They sing like angels, they play the violin, flute, organ, oboe, cello, bassoon, in a word, there is no such a bulky instrument that would make them afraid. 40 girls participate in each concert. I swear to you, there is nothing more attractive than to see a young and beautiful nun, in white clothes, with bouquets of pomegranate flowers on her ears, beating time with all grace and precision.

He enthusiastically wrote about the music of conservatories (especially under Mendicanti – the church of the mendicant) J.-J. Rousseau: “On Sundays in the churches of each of these four Scuoles, during Vespers, with a full choir and orchestra, motets composed by the greatest composers of Italy, under their personal direction, are performed exclusively by young girls, the oldest of whom is not even twenty years old. They are in the stands behind bars. Neither I nor Carrio ever missed these Vespers at the Mendicanti. But I was driven to despair by these cursed bars, which let in only sounds and hid the faces of angels of beauty worthy of these sounds. I just talked about it. Once I said the same thing to Mr. de Blond.

De Blon, who belonged to the administration of the conservatory, introduced Rousseau to the singers. “Come, Sophia,” she was terrible. “Come, Kattina,” she was crooked in one eye. “Come, Bettina,” her face was disfigured by smallpox. However, “ugliness does not exclude charm, and they possessed it,” Rousseau adds.

Entering the Conservatory of Piety, Vivaldi got the opportunity to work with the full orchestra (with brass and organ) that was available there, which was considered the best in Venice.

About Venice, its musical and theatrical life and conservatories can be judged by the following heartfelt lines of Romain Rolland: “Venice was at that time the musical capital of Italy. There, during the carnival, every evening there were performances in seven opera houses. Every evening the Academy of Music met, that is, there was a musical meeting, sometimes there were two or three such meetings in the evening. Musical celebrations took place in the churches every day, concerts lasting several hours with the participation of several orchestras, several organs and several overlapping choirs. On Saturdays and Sundays, the famous vespers were served in hospitals, those women’s conservatories, where orphans, foundling girls, or just girls with beautiful voices were taught music; they gave orchestral and vocal concerts, for which the whole of Venice went crazy ..».

By the end of the first year of his service, Vivaldi received the title of “maestro of the choir”, his further promotion is not known, it is only certain that he served as a teacher of violin and singing, and also, intermittently, as an orchestra leader and composer.

In 1713 he received leave and, according to a number of biographers, traveled to Darmstadt, where he worked for three years in the chapel of the Duke of Darmstadt. However, Pencherl claims that Vivaldi did not go to Germany, but worked in Mantua, in the duke’s chapel, and not in 1713, but from 1720 to 1723. Pencherl proves this by referring to a letter from Vivaldi, who wrote: “In Mantua I was in the service of the pious Prince of Darmstadt for three years,” and determines the time of his stay there by the fact that the title of maestro of the Duke’s chapel appears on the title pages of Vivaldi’s printed works only after 1720 of the year.

From 1713 to 1718, Vivaldi lived in Venice almost continuously. At this time, his operas were staged almost every year, with the first in 1713.

By 1717, Vivaldi’s fame had grown extraordinary. The famous German violinist Johann Georg Pisendel comes to study with him. In general, Vivaldi taught mainly performers for the orchestra of the conservatory, and not only instrumentalists, but also singers.

Suffice it to say that he was the teacher of such major opera singers as Anna Giraud and Faustina Bodoni. “He prepared a singer who bore the name of Faustina, whom he forced to imitate with her voice everything that could be performed in his time on the violin, flute, oboe.”

Vivaldi became very friendly with Pisendel. Pencherl cites the following story by I. Giller. One day Pisendel was walking along St. Stamp with “Redhead”. Suddenly he interrupted the conversation and quietly ordered to return home at once. Once at home, he explained the reason for his sudden return: for a long time, four gatherings followed and watched the young Pisendel. Vivaldi asked if his student had said any reprehensible words anywhere, and demanded that he not leave the house anywhere until he figured out the matter himself. Vivaldi saw the inquisitor and learned that Pisendel had been mistaken for some suspicious person with whom he bore a resemblance.

From 1718 to 1722, Vivaldi is not listed in the documents of the Conservatory of Piety, which confirms the possibility of his departure to Mantua. At the same time, he periodically appeared in his native city, where his operas continued to be staged. He returned to the conservatory in 1723, but already as a famous composer. Under the new conditions, he was obliged to write 2 concertos a month, with a reward of sequin per concerto, and conduct 3-4 rehearsals for them. In fulfilling these duties, Vivaldi combined them with long and distant trips. “For 14 years,” Vivaldi wrote in 1737, “I have been traveling with Anna Giraud to numerous cities in Europe. I spent three carnival seasons in Rome because of the opera. I was invited to Vienna.” In Rome, he is the most popular composer, his operatic style is imitated by everyone. In Venice in 1726 he performed as an orchestra conductor at the Theater of St. Angelo, apparently in 1728, goes to Vienna. Then three years follow, devoid of any data. Again, some introductions about the productions of his operas in Venice, Florence, Verona, Ancona shed scant light on the circumstances of his life. In parallel, from 1735 to 1740, he continued his service at the Conservatory of Piety.

The exact date of Vivaldi’s death is unknown. Most sources indicate 1743.

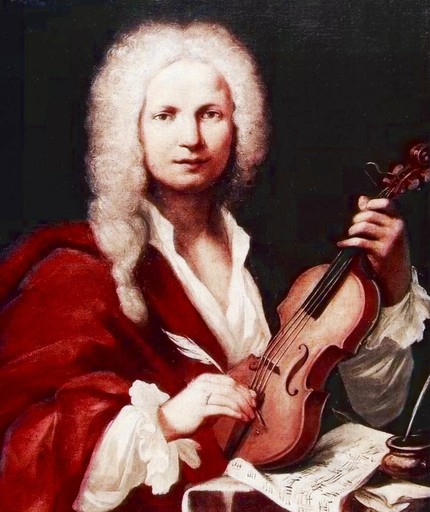

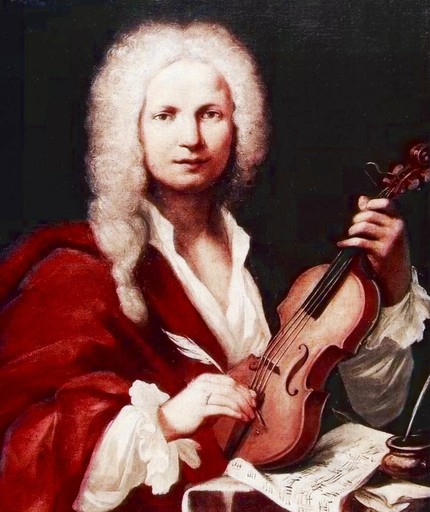

Five portraits of the great composer have survived. The earliest and most reliable, apparently, belongs to P. Ghezzi and refers to 1723. “Red-haired pop” is depicted chest-deep in profile. The forehead is slightly sloping, the long hair is curled, the chin is pointed, the lively look is full of will and curiosity.

Vivaldi was very sick. In a letter to the Marquis Guido Bentivoglio (November 16, 1737), he writes that he is forced to make his travels accompanied by 4-5 people – and all because of a painful condition. However, illness did not prevent him from being extremely active. He is on endless journeys, he directs opera productions, discusses roles with singers, struggles with their whims, conducts extensive correspondence, conducts orchestras and manages to write an incredible number of works. He is very practical and knows how to arrange his affairs. De Brosse says ironically: “Vivaldi became one of my close friends in order to sell me more expensive his concerts.” He kowtows before the mighty of this world, prudently choosing patrons, sanctimoniously religious, although by no means inclined to deprive himself of worldly pleasures. Being a Catholic priest, and, according to the laws of this religion, deprived of the opportunity to marry, for many years he was in love with his pupil, singer Anna Giraud. Their proximity caused Vivaldi great trouble. Thus, the papal legate in Ferrara in 1737 refused Vivaldi entry into the city, not only because he was forbidden to attend church services, but largely because of this reprehensible proximity. The famous Italian playwright Carlo Goldoni wrote that Giraud was ugly, but attractive – she had a thin waist, beautiful eyes and hair, a charming mouth, had a weak voice and undoubted stage talent.

The best description of Vivaldi’s personality is found in Goldoni’s Memoirs.

One day, Goldoni was asked to make some changes to the text of the libretto of the opera Griselda with music by Vivaldi, which was being staged in Venice. For this purpose, he went to Vivaldi’s apartment. The composer received him with a prayer book in his hands, in a room littered with notes. He was very surprised that instead of the old librettist Lalli, the changes should be made by Goldoni.

“- I know well, my dear sir, that you have a poetic talent; I saw your Belisarius, which I liked very much, but this is quite different: you can create a tragedy, an epic poem, if you like, and still not cope with a quatrain to set to music. Give me the pleasure of getting to know your play. “Please, please, with pleasure. Where did I put the Griselda? She was here. Deus, in adjutorium meum intende, Domine, Domine, Domine. (God, come down to me! Lord, Lord, Lord). She was just on hand. Domine adjuvandum (Lord, help). Ah, here it is, look, sir, this scene between Gualtiere and Griselda, it is a very fascinating, touching scene. The author ended it with a pathetic aria, but signorina Giraud does not like dull songs, she would like something expressive, exciting, an aria that expresses passion in various ways, for example, words interrupted by sighs, with action, movement. I don’t know if you understand me? “Yes, sir, I already understood, besides, I already had the honor of hearing Signorina Giraud, and I know that her voice is not strong. “How, sir, are you insulting my pupil?” Everything is available to her, she sings everything. “Yes, sir, you are right; give me the book and let me get to work. “No, sir, I cannot, I need her, I am very anxious. “Well, if, sir, you are so busy, then give it to me for one minute and I will immediately satisfy you.” – Immediately? “Yes, sir, immediately. The abbot, chuckling, gives me a play, paper and an inkwell, again takes up the prayer book and, walking, reads his psalms and hymns. I read the scene already known to me, remembered the wishes of the musician, and in less than a quarter of an hour I sketched an aria of 8 verses on paper, divided into two parts. I call my spiritual person and show the work. Vivaldi reads, his forehead smoothes, he rereads, utters joyful exclamations, throws his breviary on the floor and calls Signorina Giraud. She appears; well, he says, here is a rare person, here is an excellent poet: read this aria; the signor made it without getting up from his place in a quarter of an hour; then turning to me: ah, sir, excuse me. “And he hugs me, swearing that from now on I will be his only poet.”

Pencherl ends the work dedicated to Vivaldi with the following words: “This is how Vivaldi is portrayed to us when we combine all the individual information about him: created from contrasts, weak, sick, and yet alive like gunpowder, ready to get annoyed and immediately calm down, move from worldly vanity to superstitious piety, stubborn and at the same time accommodating when necessary, a mystic, but ready to go down to earth when it comes to his interests, and not at all a fool in organizing his affairs.

And how it all fits with his music! In it, the sublime pathos of the church style is combined with the indefatigable ardor of life, the high is mixed with everyday life, the abstract with the concrete. In his concerts, harsh fugues, mournful majestic adagios and, along with them, songs of the common people, lyrics coming from the heart, and a cheerful dance sound. He writes program works – the famous cycle “The Seasons” and supplies each concert with frivolous bucolic stanzas for the abbot:

Spring has come, solemnly announces. Her merry round dance, and the song in the mountains sounds. And the brook murmurs towards her affably. Zephyr wind caresses the whole nature.

But suddenly it got dark, lightning shone, Spring is a harbinger – thunder swept through the mountains And soon fell silent; and the lark’s song, Dispersed in the blue, they rush along the valleys.

Where the carpet of flowers of the valley covers, Where tree and leaf tremble in the breeze, With a dog at his feet, the shepherd is dreaming.

And again Pan can listen to the magic flute To the sound of her, the nymphs dance again, Welcoming the Sorceress-spring.

In Summer, Vivaldi makes the cuckoo crow, the turtle dove coo, the goldfinch chirp; in “Autumn” the concert begins with the song of the villagers returning from the fields. He also creates poetic pictures of nature in other program concerts, such as “Storm at Sea”, “Night”, “Pastoral”. He also has concerts that depict the state of mind: “Suspicion”, “Rest”, “Anxiety”. His two concertos on the theme “Night” can be considered the first symphonic nocturnes in world music.

His writings amaze with the richness of imagination. With an orchestra at his disposal, Vivaldi is constantly experimenting. The solo instruments in his compositions are either severely ascetic or frivolously virtuosic. Motority in some concerts gives way to generous songwriting, melodiousness in others. Colorful effects, play of timbres, such as in the middle part of the Concerto for three violins with a charming pizzicato sound, are almost “impressionistic”.

Vivaldi created with phenomenal speed: “He is ready to bet that he can compose a concerto with all his parts faster than a scribe can rewrite it,” wrote de Brosse. Perhaps this is where the spontaneity and freshness of Vivaldi’s music comes from, which has delighted listeners for more than two centuries.

L. Raaben, 1967