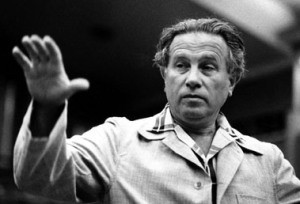

Antal Doráti (Antal Doráti) |

Doráti Antal

There are few conductors who own as many records as Antalu Dorati. A few years ago, American firms gave him a gold record – for one and a half million discs sold; and a year later they had to give the conductor another such award for the second time. “Probably a world record!” exclaimed one of the critics. The intensity of Dorati’s artistic activity is enormous. There is almost no major orchestra in Europe with which he would not perform annually; the conductor gives dozens of concerts a year, barely managing to fly from one country to another by plane. And in the summer – festivals: Venice, Montreux, Lucerne, Florence … The rest of the time is recording on records. And finally, in short intervals, when the artist is not at the console, he manages to compose music: only in recent years he has written cantatas, a cello concerto, a symphony and many chamber ensembles.

When asked where he finds time for all this, Dorathy replies: “It’s quite simple. I get up every day at 7 o’clock in the morning and work from seven to half past nine. Sometimes even in the evening. It is very important that I was taught as a child to concentrate work. At home, in Budapest, it has always been like this: in one room, my father gave violin lessons, in the other, my mother played the piano.

Dorati is Hungarian by nationality. Bartok and Kodai often visited his parents’ house. Dorati decided at a young age to become a conductor. Already at the age of fourteen, he organized a student orchestra in his gymnasium, and at eighteen he simultaneously received a gymnasium certificate and a diploma from the Academy of Music in piano (from E. Donany) and composition (from L. Weiner). He was accepted as an assistant conductor at the opera. Proximity to the circle of progressive musicians helped Dorati to keep abreast of all the latest in modern music, and work in the opera contributed to the acquisition of the necessary experience.

In 1928, Dorati leaves Budapest and goes abroad. He works as a conductor in the theaters of Munich and Dresden, gives concerts. The desire to travel led him to Monte Carlo, to the post of chief conductor of the Russian Ballet – the successor to the Diaghilev troupe. For many years – from 1934 to 1940 – Dorati toured with the Monte Carlo Ballet in Europe and America. American concert organizations drew attention to the conductor: in 1937 he made his debut with the National Symphony Orchestra in Washington, in 1945 he was invited as chief conductor in Dallas, and four years later he replaced Mitropoulos as the head of the orchestra in Minneapolis, where he remained for twelve years.

These years are the most significant in the biography of the conductor; in all its brilliance, his abilities as an educator and organizer were manifested. Mitropoulos, being a brilliant artist, did not like painstaking work with the orchestra and left the team in poor condition. Dorati very soon raised it to the level of the best American orchestras, famous for their discipline, evenness of sound and ensemble coherence. In recent years, Dorathy has mainly worked in England, from where he makes his numerous concert tours. With great success were his performances “in his homeland, “A good conductor must have two qualities,” says Dorati, “first, pure musical nature: he must understand and feel the music. This goes without saying. The second seems to have nothing to do with music: the conductor must be able to give orders. But in the art of “ordering” means something quite different than, say, in the army. In art, you can’t give orders just because you’re a higher rank: the musicians must want to play the way the conductor tells them to.

It is the musicality and clarity of his concepts that attracts Dorati. Long-term work with ballet taught him rhythmic discipline. He especially subtly conveys colorful ballet music. This is confirmed, in particular, by his recordings of Stravinsky’s The Firebird, Borodin’s Polovtsian Dances, the suite from Delibes’ Coppélia, and his own suite of waltzes by J. Strauss.

Constant leadership of a large symphony orchestra helped Dorati not to limit his repertoire to fifteen classical and contemporary works, but to constantly expand it. This is evidenced by a cursory list of his other most common recordings. Here we find many of Beethoven’s symphonies, Tchaikovsky’s Fourth and Sixth, Dvorak’s Fifth, Rimsky-Korsakov’s Scheherazade, Bartók’s The Bluebeard’s Castle, Liszt’s Hungarian Rhapsodies and Enescu’s Romanian Rhapsodies, excerpts from Wozzeck and Lulu by A. Berg, plays by Schoenberg and Webern, “An American in Paris” by Gershwin, many instrumental concerts in which Dorati acts as a subtle and equal partner of such soloists as G. Shering, B. Jainis, and other famous artists.

“Contemporary Conductors”, M. 1969.