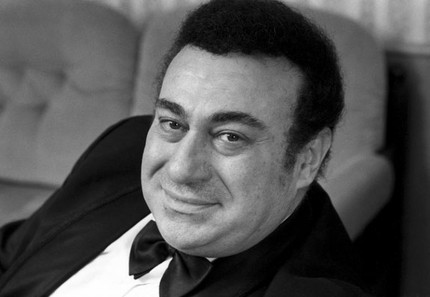

Zurab Lavrentievich Sotkilava |

Zurab Sotkilava

The name of the singer is known today to all lovers of opera both in our country and abroad, where he tours with constant success. They are captivated by the beauty and power of the voice, the noble manner, high skill, and most importantly, the emotional dedication that accompanies each performance of the artist both on the theater stage and on the concert stage.

Zurab Lavrentievich Sotkilava was born on March 12, 1937 in Sukhumi. “First, I should probably say about genes: my grandmother and mother played the guitar and sang great,” says Sotkilava. – I remember they sat on the street near the house, performed old Georgian songs, and I sang along with them. I did not think about any singing career either then or later. Interestingly, many years later, my father, who has no hearing at all, supported my operatic endeavors, and my mother, who has absolute pitch, was categorically against it.

And yet, in childhood, Zurab’s main love was not singing, but football. Over time, he showed good abilities. He got into the Sukhumi Dynamo, where at the age of 16 he was considered a rising star. Sotkilava played in the place of the wingback, he joined the attacks a lot and successfully, running a hundred meters in 11 seconds!

In 1956, Zurab became the captain of the Georgian national team at the age of 20. Two years later, he got into the main team of Dynamo Tbilisi. The most memorable for Sotkilava was the game with Dynamo Moscow.

“I am proud that I went on the field against Lev Yashin himself,” recalls Sotkilava. – We got to know Lev Ivanovich better, already when I was a singer and was friends with Nikolai Nikolaevich Ozerov. Together we went to Yashin to the hospital after the operation … Using the example of the great goalkeeper, I was once again convinced that the more a person has achieved in life, the more modest he is. And we lost that match with a score of 1:3.

By the way, this was my last game for Dynamo. In one of the interviews, I said that the forward of the Muscovites Urin made me a singer, and many people thought that he had crippled me. In no case! He just outright outplayed me. But it was half the trouble. Soon we flew to Yugoslavia, where I got a fracture and left the squad. In 1959 he tried to return. But the trip to Czechoslovakia finally put an end to my football career. There I received another serious injury, and after some time I was expelled …

… In 58, when I played in Dinamo Tbilisi, I came home to Sukhumi for a week. Once, the pianist Valeria Razumovskaya, who always admired my voice and said who I would eventually become, dropped in on my parents. At that time I did not attach any importance to her words, but nevertheless I agreed to come to some visiting professor of the conservatory from Tbilisi for an audition. My voice didn’t make much of an impression on him. And here, imagine, football again played a decisive role! At that time, Meskhi, Metreveli, Barkaya were already shining at Dynamo, and it was impossible to get a ticket to the stadium. So, at first, I became a supplier of tickets for the professor: he came to pick them up at the Dynamo base in Digomi. In gratitude, the professor invited me to his home, we began to study. And suddenly he tells me that in just a few lessons I have made great progress and I have an operatic future!

But even then, the prospect made me laugh. I seriously thought about singing only after I was expelled from Dynamo. The professor listened to me and said: “Well, stop getting dirty in the mud, let’s do a clean job.” And a year later, in July 60, I first defended my diploma at the Mining Faculty of the Tbilisi Polytechnic Institute, and a day later I was already taking exams at the conservatory. And was accepted. By the way, we studied at the same time as Nodar Akhalkatsi, who preferred the Institute of Railway Transport. We had such battles in inter-institutional football tournaments that the stadium for 25 thousand spectators was packed!”

Sotkilava came to the Tbilisi Conservatory as a baritone, but soon Professor D.Ya. Andguladze corrected the mistake, of course, the new student has a magnificent lyric-dramatic tenor. In 1965, the young singer made his debut on the Tbilisi stage as Cavaradossi in Puccini’s Tosca. The success exceeded all expectations. Zurab performed at the Georgian State Opera and Ballet Theater from 1965 to 1974. The talent of a promising singer at home was sought to be supported and developed, and in 1966 Sotkilava was sent for an internship at the famous Milan theater La Scala.

There he trained with the best bel canto specialists. He worked tirelessly, and after all, his head could have been spinning after the words of maestro Genarro Barra, who then wrote: “Zurab’s young voice reminded me of the tenors of bygone times.” It was about the times of E. Caruso, B. Gigli and other sorcerers of the Italian scene.

In Italy, the singer improved for two years, after which he took part in the festival of young vocalists “Golden Orpheus”. His performance was triumphant: Sotkilava won the main prize of the Bulgarian festival. Two years later – a new success, this time at one of the most important International competitions – named after P.I. Tchaikovsky in Moscow: Sotkilava was awarded the second prize.

After a new triumph, in 1970, – First Prize and Grand Prix at the F. Viñas International Vocal Competition in Barcelona – David Andguladze said: “Zurab Sotkilava is a gifted singer, very musical, his voice, of an unusually beautiful timbre, does not leaves the listener indifferent. The vocalist emotionally and vividly conveys the nature of the performed works, fully reveals the composer’s intention. And the most remarkable feature of his character is diligence, the desire to comprehend all the secrets of art. He studies every day, we have almost the same “schedule of lessons” as in his student years.

On December 30, 1973, Sotkilava made his debut on the stage of the Bolshoi Theater as Jose.

“At first glance,” he recalls, “it may seem that I quickly got used to Moscow and easily entered the Bolshoi Opera team. But it’s not. At first it was difficult for me, and many thanks to the people who were next to me at that time. And Sotkilava names the director G. Pankov, the concertmaster L. Mogilevskaya and, of course, his partners in performances.

The premiere of Verdi’s Otello at the Bolshoi Theater was a remarkable event, and Sotkilava’s Otello was a revelation.

“Working on the part of Othello,” Sotkilava said, “opened up new horizons for me, forced me to reconsider much of what had been done, gave birth to other creative criteria. The role of Othello is the peak from which one can clearly see, although it is difficult to reach it. Now, when there is no human depth, psychological complexity in this or that image offered by the score, it is not so interesting to me. What is the happiness of an artist? Waste yourself, your nerves, spend on wear and tear, not thinking about the next performance. But work should make you want to waste yourself like that, for this you need big tasks that are interesting to solve … “

Another outstanding achievement of the artist was the role of Turiddu in Mascagni’s Rural Honor. First on the concert stage, then at the Bolshoi Theater, Sotkilava achieved tremendous power of figurative expressiveness. Commenting on this work, the singer emphasizes: “Country Honor is a verist opera, an opera of high intensity of passions. It is possible to convey this in a concert performance, which, of course, should not be reduced to abstract music-making from a book with musical notation. The main thing is to take care of gaining inner freedom, which is so necessary for the artist both on the opera stage and on the concert stage. In the music of Mascagni, in his opera ensembles, there are multiple repetitions of the same intonations. And here it is very important for the performer to remember the danger of monotony. Repeating, for example, one and the same word, you need to find the undercurrent of musical thought, coloring, shading the various semantic meanings of this word. There is no need to artificially inflate yourself and it is not known what to play. The pathetic intensity of passion in Rural Honor must be pure and sincere.”

The strength of Zurab Sotkilava’s art is that it always brings people sincere purity of feeling. This is the secret of his continued success. The singer’s foreign tours were no exception.

“One of the most brilliantly beautiful voices that exists anywhere today.” This is how the reviewer responded to the performance of Zurab Sotkilava at the Champs-Elysées Theater in Paris. This was the beginning of the foreign tour of the wonderful Soviet singer. Following the “shock of discovery” followed by new triumphs – a brilliant success in the United States and then in Italy, in Milan. The ratings of the American press were also enthusiastic: “A large voice of excellent evenness and beauty in all registers. The artistry of Sotkilava comes directly from the heart.”

The 1978 tour made the singer a world-famous celebrity – numerous invitations to participate in performances, concerts, and recordings followed …

In 1979, his artistic merits were awarded the highest award – the title of People’s Artist of the USSR.

“Zurab Sotkilava is the owner of a tenor of rare beauty, bright, sonorous, with brilliant upper notes and a strong middle register,” writes S. Savanko. “Voices of this magnitude are rare. Excellent natural data were developed and strengthened by the professional school, which the singer passed in his homeland and in Milan. Sotkilava’s performing style is dominated by signs of classical Italian bel canto, which is especially felt in the singer’s opera activity. The core of his stage repertoire is lyrical and dramatic roles: Othello, Radamès (Aida), Manrico (Il trovatore), Richard (Un ballo in maschera), José (Carmen), Cavaradossi (Tosca). He also sings Vaudemont in Tchaikovsky’s Iolanthe, as well as in Georgian operas – Abesalom in the Tbilisi Opera Theater’s Abesalom and Eteri by Z. Paliashvili and Arzakan in O. Taktakishvili’s The Abduction of the Moon. Sotkilava subtly feels the specifics of each part, it is no coincidence that the breadth of the stylistic range inherent in the art of the singer was noted in critical responses.

“Sotkilava is a classic hero-lover of the Italian opera,” says E. Dorozhkin. – All G. – obviously his: Giuseppe Verdi, Giacomo Puccini. However, there is one significant “but”. Of the entire set necessary for the image of a womanizer, Sotkilava fully possesses, as the enthusiastic Russian president rightly noted in his message to the hero of the day, only “an amazingly beautiful voice” and “natural artistry.” In order to enjoy the same love of the public as Georgesand’s Andzoletto (namely, this kind of love surrounds the singer now), these qualities are not enough. Wise Sotkilava, however, did not seek to acquire others. He took not by number, but by skill. Completely ignoring the light disapproving whisper of the hall, he sang Manrico, the Duke and Radamès. This, perhaps, is the only thing in which he was and remains a Georgian – to do his job, no matter what, not for a second doubting his own merits.

The last stage bastion that Sotkilava took was Mussorgsky’s Boris Godunov. Sotkilava sang the impostor – the most Russian of all the Russian characters in Russian opera – in a way that the blue-eyed blond singers, who fiercely followed what was happening from the dusty backstage, never dreamed of singing. The absolute Timoshka came out – and in fact, Grishka Otrepyev was Timoshka.

Sotkilava is a secular person. And secular in the best sense of the word. Unlike many of his colleagues in the artistic workshop, the singer dignifies with the presence not only those events that are inevitably followed by a plentiful buffet table, but also those that are intended for true connoisseurs of beauty. Sotkilava earns money on a jar of olives with anchovies himself. And the singer’s wife also cooks wonderfully.

Sotkilava performs, although not often, on the concert stage. Here his repertoire consists mainly of Russian and Italian music. At the same time, the singer tends to focus specifically on the chamber repertoire, on romance lyrics, relatively rarely turning to concert performances of opera excerpts, which is quite common in vocal programs. Plastic relief, bulge of dramatic solutions are combined in Sotkilava’s interpretation with special intimacy, lyrical warmth and softness, which are rare in a singer with such a large-scale voice.

Since 1987, Sotkilava has been teaching solo singing at the Moscow State P.I. Tchaikovsky.

PS Zurab Sotkilava died in Moscow on September 18, 2017.