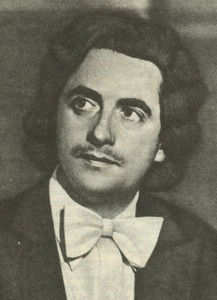

Walter Gieseking |

Walter Gieseking

Two cultures, two great musical traditions nourished the art of Walter Gieseking, merged in his appearance, giving him unique features. It was as if fate itself was destined for him to enter the history of pianism as one of the greatest interpreters of French music and at the same time one of the most original performers of German music, to which his playing gave rare grace, purely French lightness and grace.

The German pianist was born and spent his youth in Lyon. His parents were engaged in medicine and biology, and the propensity for science was passed on to his son – until the end of his days he was a passionate ornithologist. He began to study music seriously relatively late, although he studied from the age of 4 (as is customary in an intelligent home) to play the piano. Only after the family moved to Hanover, he began to take lessons from the prominent teacher K. Laimer and soon entered his conservatory class.

- Piano music in the online store OZON.ru

The ease with which he learned was amazing. At the age of 15, he attracted attention beyond his years with a subtle interpretation of four Chopin ballads, and then gave six concerts in a row, in which he performed all 32 Beethoven sonatas. “The most difficult thing was to learn everything by heart, but this was not too difficult,” he later recalled. And there was no boasting, no exaggeration. War and military service briefly interrupted Gieseking’s studies, but already in 1918 he graduated from the conservatory and very quickly gained wide popularity. The basis of his success was both phenomenal talent and his consistent application in his own practice of a new method of study, developed jointly with teacher and friend Karl Leimer (in 1931 they published two small brochures outlining the basics of their method). The essence of this method, as noted by the Soviet researcher Professor G. Kogan, “consisted in the extremely concentrated mental work on the work, mainly without an instrument, and in the instantaneous maximum relaxation of the muscles after each effort during the performance.” One way or another, but Gieseknng developed a truly unique memory, which allowed him to learn the most complex works with fabulous speed and accumulate a huge repertoire. “I can learn by heart anywhere, even on a tram: the notes are imprinted in my mind, and when they get there, nothing will make them disappear,” he admitted.

The pace and methods of his work on new compositions were legendary. They told how one day, visiting the composer M. Castel Nuovo Tedesco, he saw a manuscript of a new piano suite on his piano stand. Having played it right there “from sight”, Gieseking asked for the notes for one day and returned the next day: the suite was learned and soon sounded in a concert. And the most difficult concerto by another Italian composer G. Petrassi Gieseking learned in 10 days. In addition, the technical freedom of the game, which was innate and developed over the years, gave him the opportunity to practice relatively little – no more than 3-4 hours a day. In a word, it is not surprising that the pianist’s repertoire was practically boundless already in the 20s. A significant place in it was occupied by modern music, he played, in particular, many works by Russian authors – Rachmaninoff, Scriabin. Prokofiev. But the real fame brought him the performance of the works of Ravel, Debussy, Mozart.

Gieseking’s interpretation of the work of the luminaries of French impressionism struck with an unprecedented richness of colors, the finest shades, the delightful relief of recreating all the details of the unsteady musical fabric, the ability to “stop the moment”, to convey to the listener all the moods of the composer, the fullness of the picture captured by him in the notes. The authority and recognition of Gieseking in this area were so indisputable that the American pianist and historian A. Chesins once remarked in connection with the performance of Debussy’s “Bergamas Suite”: “Most of the musicians present would hardly have had the courage to challenge the publisher’s right to write : „Private property of Walter Gieseking. Don’t intrude.” Explaining the reasons for his continued success in the performance of French music, Gieseking wrote: “It has already been repeatedly tried to find out why it is precisely in an interpreter of German origin that such far-reaching associations with truly French music are found. The simplest and, moreover, summative answer to this question would be: music has no boundaries, it is a “national” speech, understandable to all peoples. If we consider this to be indisputably correct, and if the impact of musical masterpieces covering all countries of the world is a constantly renewing source of joy and satisfaction for the performing musician, then this is precisely the explanation for such an obvious means of musical perception … At the end of 1913, at the Hanover Conservatory, Karl Leimer recommended me to learn “Reflections in Water” from the first book of “Images”. From a “writer’s” point of view, it would probably be very effective to talk about a sudden insight that seemed to have made a revolution in my mind, about a kind of musical “thunderbolt”, but the truth commands to admit that nothing of the kind happened. I just really liked the works of Debussy, I found them exceptionally beautiful and immediately decided to play them as much as possible…” wrong” is simply impossible. You are convinced of this again and again, referring to the complete works of these composers in Gieseking’s recording, which retains its freshness to this day.

Much more subjective and controversial seems to many another favorite area of the artist’s work – Mozart. And here the performance abounds in many subtleties, distinguished by elegance and purely Mozartian lightness. But still, according to many experts, Gieseking’s Mozart entirely belonged to the archaic, frozen past – the XNUMXth century, with its court rituals, gallant dances; there was nothing in him from the author of Don Juan and the Requiem, from the harbinger of Beethoven and the romantics.

Undoubtedly, the Mozart of Schnabel or Clara Haskil (if we talk about those who played at the same time as Gieseking) is more in line with the ideas of our days and comes closer to the ideal of the modern listener. But Gieseking’s interpretations do not lose their artistic value, perhaps primarily because, having passed by the drama and philosophical depths of music, he was able to comprehend and convey the eternal illumination, love of life that are inherent in everything – even the most tragic pages of this composer’s work.

Gieseking left one of the most complete sounding collections of Mozart’s music. Assessing this enormous work, the West German critic K.-H. Mann noted that “in general, these recordings are distinguished by an unusually flexible sound and, moreover, an almost painful clarity, but also by an amazingly wide scale of expressiveness and purity of pianistic touch. This is entirely in keeping with Gieseking’s conviction that in this way the purity of sound and the beauty of expression are combined, so that the perfect interpretation of the classical form does not diminish the strength of the composer’s deepest feelings. These are the laws according to which this performer played Mozart, and only on the basis of them can one fairly evaluate his game.

Of course, Gieseking’s repertoire was not limited to these names. He played Beethoven a lot, he also played in his own way, in the spirit of Mozart, refusing any pathos, from romanticization, striving for clarity, beauty, sound, harmony of proportions. The originality of his style left the same imprint on the performance of Brahms, Schumann, Grieg, Frank and others.

It should be emphasized that, although Gieseking remained true to his creative principles throughout his life, in the last, post-war decade, his playing acquired a slightly different character than before: the sound, while retaining its beauty and transparency, became fuller and deeper, the mastery was absolutely fantastic. pedaling and the subtlety of pianissimo, when a barely audible hidden sound reached the far rows of the hall; finally, the highest precision was combined with sometimes unexpected – and all the more impressive – passion. It was during this period that the best recordings of the artist were made – collections of Bach, Mozart, Debussy, Ravel, Beethoven, records with concerts of romantics. At the same time, the accuracy and perfection of his playing were such that most of the records were recorded without preparation and almost without repetition. This allows them to at least partially convey the charm that his playing in the concert hall radiated.

In the post-war years, Walter Gieseking was full of energy, was in the prime of his life. Since 1947, he taught a piano class at the Saarbrücken Conservatory, putting into practice the system of education of young pianists developed by him and K. Laimer, made long concert trips, and recorded a lot on records. In early 1956, the artist got into a car accident in which his wife died, and he was seriously injured. However, three months later, Gieseking reappeared on the Carnegie Hall stage, performing with the orchestra under the baton of Guido Cantelli Beethoven’s Fifth Concerto; the next day, New York newspapers stated that the artist had fully recovered from the accident and his skill had not faded at all. It seemed that his health was completely restored, but after another two months he died suddenly in London.

Gieseking’s legacy is not only his records, his pedagogical method, his numerous students; The master wrote the most interesting book of memoirs “So I Became a Pianist”, as well as chamber and piano compositions, arrangements, and editions.

Cit.: So I became a pianist / / Performing art of foreign countries. – M., 1975. Issue. 7.

Grigoriev L., Platek Ya.