Nuances in Music: Tempo (Lesson 11)

With this lesson, we will begin a series of lessons dedicated to various nuances in music.

What makes music truly unique, unforgettable? How to get away from the facelessness of a piece of music, to make it bright, interesting to listen to? What means of musical expression do composers and performers use to achieve this effect? We will try to answer all these questions.

I hope that everyone knows or guesses that composing music is not only writing a harmonious series of notes … Music is also communication, communication between the composer and the performer, the performer with the audience. Music is a peculiar, extraordinary speech of the composer and performer, with the help of which they reveal to the listeners all the innermost things that are hidden in their souls. It is with the help of musical speech that they establish contact with the public, win its attention, evoke an emotional response from it.

As in speech, in music the two primary means of conveying emotion are tempo (speed) and dynamics (loudness). These are the two main tools that are used to turn well-measured notes on a letter into a brilliant piece of music that will not leave anyone indifferent.

In this lesson, we will talk about pace.

Pace means “time” in Latin, and when you hear someone talking about the tempo of a piece of music, it means that the person is referring to the speed at which it should be played.

The meaning of tempo will become clearer if we recall the fact that initially music was used as a musical accompaniment to dance. And it was the movement of the dancers’ feet that set the pace of the music, and the musicians followed the dancers.

Ever since the invention of musical notation, composers have tried to find some way to accurately reproduce the tempo at which recorded works should be played. This was supposed to greatly simplify reading the notes of an unfamiliar piece of music. Over time, they noticed that each work has an internal pulsation. And this pulsation is different for each work. Like the heart of each person, it beats differently, at different speeds.

So, if we need to determine the pulse, we count the number of heart beats per minute. So it is in music – to record the speed of the pulsation, they began to record the number of beats per minute.

To help you understand what a meter is and how to determine it, I suggest you take a watch and stamp your foot every second. Do you hear? You tap one share, or one bit per second. Now, looking at your watch, tap your foot twice a second. There was another pulse. The frequency with which you stamp your foot is called at a pace (or meter). For example, when you stamp your foot once per second, the tempo is 60 beats per minute, because there are 60 seconds in a minute, as we know. We stomp twice a second, and the pace is already 120 beats per minute.

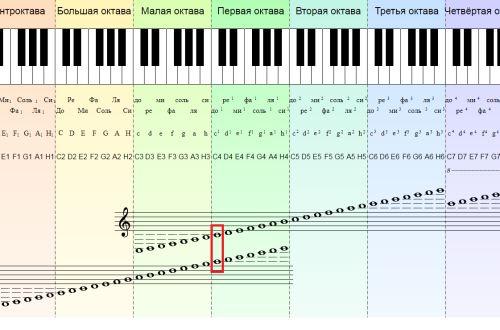

In music notation, it looks something like this:

![]()

This designation tells us that a quarter note is taken as a unit of pulsation, and this pulsation goes with a frequency of 60 beats per minute.

Here’s another example:

Here, too, a quarter duration is taken as a unit of pulsation, but the pulsation speed is twice as fast – 120 beats per minute.

There are other examples when not a quarter, but an eighth or half duration, or some other one, is taken as a pulsation unit … Here are a few examples:

![]()

In this version, the song “It’s Cold in the Winter for a Little Christmas Tree” will sound twice as fast as the first version, since the duration is twice as short as a unit of meter – instead of a quarter, an eighth.

Such designations of tempo are most often found in modern sheet music. Composers of the past eras used mostly verbal description of the tempo. Even today, the same terms are used to describe the tempo and speed of performance as then. These are Italian words, because when they came into use, the bulk of music in Europe was composed by Italian composers.

The following are the most common notation for tempo in music. In brackets for convenience and a more complete idea of the tempo, the approximate number of beats per minute for a given tempo is given, because many people have no idea how fast or how slow this or that tempo should sound.

- Grave – (grave) – the slowest pace (40 beats / min)

- Largo – (largo) – very slowly (44 beats / min)

- Lento – (lento) – slowly (52 beats / min)

- Adagio – (adagio) – slowly, calmly (58 beats / min)

- Andante – (andante) – slowly (66 beats / min)

- Andantino – (andantino) – leisurely (78 beats / min)

- Moderato – (moderato) – moderately (88 beats / min)

- Allegretto – (allegretto) – pretty fast (104 beats / min)

- Allegro – (allegro) – fast (132 bpm)

- Vivo – (vivo) – lively (160 beats / min)

- Presto – (presto) – very fast (184 beats / min)

- Prestissimo – (prestissimo) – extremely fast (208 beats / min)

However, tempo does not necessarily indicate how fast or slow the piece should be played. The tempo also sets the general mood of the piece: for example, music played very, very slowly, at the grave tempo, evokes the deepest melancholy, but the same music, if performed very, very quickly, at the prestissimo tempo, will seem incredibly joyful and bright to you. Sometimes, to clarify the character, composers use the following additions to the notation of tempo:

- light – легко

- cantabile – melodiously

- dolce — gently

- mezzo voce – half a voice

- sonore – sonorous (not to be confused with screaming)

- lugubre — gloomy

- pesante – heavy, weighty

- funebre — mourning, funeral

- festivo – festive (festival)

- quasi rithmico – emphasized (exaggerated) rhythmically

- misterioso – mysteriously

Such remarks are written not only at the beginning of the work, but may also appear inside it.

To confuse you a little more, let’s say that in combination with tempo notation, auxiliary adverbs are sometimes used to clarify shades:

- molto – very,

- assai – very,

- con moto – with mobility, commodo – convenient,

- non troppo – not too much

- non tanto – not so much

- sempre – all the time

- meno mosso – less mobile

- piu mosso – more mobile.

For example, if the tempo of a piece of music is poco allegro (poco allegro), then this means that the piece needs to be played “quite briskly”, and poco largo (poco largo) would mean “rather slowly”.

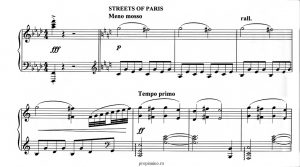

Sometimes individual musical phrases in a piece are played at a different tempo; this is done to give greater expressiveness to the musical work. Here are a few notations for changing tempo that you may encounter in music notation:

To slow down:

- ritenuto – holding back

- ritardando – being late

- allargando – expanding

- rallentando – slowing down

To speed up:

- accelerando – accelerating,

- animando – inspiring

- stringendo – accelerating

- stretto – compressed, squeezing

To return the movement to the original tempo, the following notations are used:

- a tempo – at a pace,

- tempo primo – initial tempo,

- tempo I – initial tempo,

- l’istesso tempo – the same tempo.

Finally, I will tell you that you are not afraid of so much information that you can not memorize these designations by heart. There are many reference books on this terminology.

Before playing a piece of music, you just need to pay attention to the designation of the tempo, and look for its translation in the reference book. But, of course, you first need to learn a piece at a very slow pace, and then play it at a given pace, taking into account all the remarks throughout the whole piece.