Musical culture of romanticism: aesthetics, themes, genres and musical language

Contents

Zweig was right: Europe has not seen such a wonderful generation as the romantics since the Renaissance. Marvelous images of the dream world, naked feelings and the desire for sublime spirituality – these are the colors that paint the musical culture of romanticism.

The emergence of romanticism and its aesthetics

While the industrial revolution was taking place in Europe, the hopes placed on the Great French Revolution were crushed in the hearts of Europeans. The cult of reason, proclaimed by the Age of Enlightenment, was overthrown. The cult of feelings and the natural principle in man has ascended to the pedestal.

This is how romanticism appeared. In musical culture it existed for a little more than a century (1800-1910), while in related fields (painting and literature) its term expired half a century earlier. Perhaps music is “to blame” for this – it was music that was at the top among the arts among the romantics as the most spiritual and freest of the arts.

However, the romantics, unlike representatives of the eras of antiquity and classicism, did not build a hierarchy of arts with its clear division into types and genres. The romantic system was universal; the arts could freely transform into each other. The idea of a synthesis of arts was one of the key ones in the musical culture of romanticism.

This relationship also concerned the categories of aesthetics: the beautiful was combined with the ugly, the high with the base, the tragic with the comic. Such transitions were connected by romantic irony, which also reflected a universal picture of the world.

Everything that had to do with beauty took on a new meaning among the romantics. Nature became an object of worship, the artist was idolized as the highest of mortals, and feelings were exalted over reason.

Spiritless reality was contrasted with a dream, beautiful but unattainable. The romantic, with the help of his imagination, built his new world, unlike other realities.

What themes did Romantic artists choose?

The interests of the romantics were clearly manifested in the choice of themes they chose in art.

- Theme of loneliness. An underrated genius or a lonely person in society – these were the main themes among composers of this era (“The Love of a Poet” by Schumann, “Without the Sun” by Mussorgsky).

- Theme of “lyrical confession”. In many opuses of romantic composers there is a touch of autobiography (“Carnival” by Schumann, “Symphony Fantastique” by Berlioz).

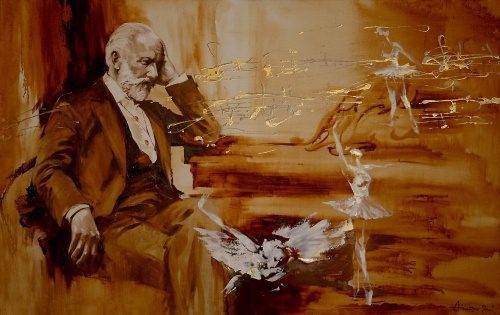

- Love theme. Basically, this is the theme of unrequited or tragic love, but not necessarily (“Love and Life of a Woman” by Schumann, “Romeo and Juliet” by Tchaikovsky).

- Path Theme. She is also called theme of wanderings. The romantic soul, torn by contradictions, was looking for its path (“Harold in Italy” by Berlioz, “The Years of Wandering” by Liszt).

- Death theme. Basically it was spiritual death (Tchaikovsky’s Sixth Symphony, Schubert’s Winterreise).

- Nature theme. Nature in the eyes of romance and a protective mother, and an empathetic friend, and punishing fate (“The Hebrides” by Mendelssohn, “In Central Asia” by Borodin). The cult of the native land (polonaises and ballads of Chopin) is also connected with this theme.

- Fantasy theme. The imaginary world for romantics was much richer than the real one (“The Magic Shooter” by Weber, “Sadko” by Rimsky-Korsakov).

Musical genres of the Romantic era

The musical culture of romanticism gave impetus to the development of the genres of chamber vocal lyrics: (“The Forest King” by Schubert), (“The Maiden of the Lake” by Schubert) and, often combined into (“Myrtles” by Schumann).

was distinguished not only by the fantastic nature of the plot, but also by the strong connection between words, music and stage action. The opera is being symphonized. Suffice it to recall Wagner’s “Ring of the Nibelungs” with its developed network of leitmotifs.

Among the instrumental genres, romance is distinguished. To convey one image or a momentary mood, a short play is enough for them. Despite its scale, the play bubbles with expression. It can be (like Mendelssohn), or plays with programmatic titles (“The Rush” by Schumann).

Like songs, plays are sometimes combined into cycles (“Butterflies” by Schumann). At the same time, the parts of the cycle, brightly contrasting, always formed a single composition due to musical connections.

The Romantics loved program music, which combined it with literature, painting or other arts. Therefore, the plot in their works often controlled the form. One-movement sonatas (Liszt’s B minor sonata), one-movement concertos (Liszt’s First Piano Concerto) and symphonic poems (Liszt’s Preludes), and a five-movement symphony (Berlioz’s Symphony Fantastique) appeared.

The musical language of romantic composers

The synthesis of arts, glorified by the romantics, influenced the means of musical expression. The melody has become more individual, sensitive to the poetics of the word, and the accompaniment has ceased to be neutral and typical in texture.

The harmony was enriched with unprecedented colors to tell about the experiences of the romantic hero. Thus, the romantic intonations of languor perfectly conveyed altered harmonies that increased tension. Romantics loved the effect of chiaroscuro, when the major was replaced by the minor of the same name, and the chords of the side steps, and the beautiful comparisons of tonalities. New effects were also discovered in natural modes, especially when it was necessary to convey the folk spirit or fantastic images in music.

In general, the melody of the romantics strived for continuity of development, rejected any automatic repetition, avoided regularity of accents and breathed expressiveness in each of its motives. And texture has become such an important link that its role is comparable to the role of melody.

Listen to what a wonderful mazurka Chopin has!

Instead of a conclusion

The musical culture of romanticism at the turn of the 19th and 20th centuries experienced the first signs of crisis. The “free” musical form began to disintegrate, harmony prevailed over melody, the sublime feelings of the romantic soul gave way to painful fear and base passions.

These destructive trends brought Romanticism to an end and opened the way for Modernism. But, having ended as a movement, romanticism continued to live both in the music of the 20th century and in the music of the current century in its various components. Blok was right when he said that romanticism arises “in all eras of human life.”