Meter |

from the Greek métron – measure or measure

In music and poetry, rhythmic orderliness based on the observance of a certain measure that determines the magnitude of rhythmic constructions. In accordance with this measure, verbal and musical the text, in addition to the semantic (syntactic) articulation, is divided into metric. units – verses and stanzas, measures, etc. Depending on the features that define these units (duration, number of stresses, etc.), the systems of musical instruments differ (metric, syllabic, tonic, etc. – in versification, mensural and clock – in music), each of which may include many partial meters (schemes for constructing metric units) united by a common principle (for example, in a clock system, the sizes are 4/4, 3/2, 6/8, etc.). In metric the scheme includes only mandatory signs of metric. units, while other rhythmic. elements remain free and create rhythmic. variety within a given meter. Rhythm without meter is possible—the rhythm of prose, in contrast to verse (“measured,” “measured” speech), the free rhythm of Gregorian chant, and so on. In the music of modern times, there is a designation for free rhythm senza misura. Modern ideas about M. in music means. to a certain extent depend on the concept of poetic music, which, however, itself arose at the stage of the inseparable unity of verse and music and was originally essentially musical. With the disintegration of musical-verse unity, specific systems of poetry and music. M., similar in that M. in them regulates accentuation, and not duration, as in ancient metric. versification or in medieval mensural (from lat. mensura – measure) music. Numerous disagreements in the understanding of M. and his relationship to rhythm are due to Ch. arr. the fact that the characteristic features of one of the systems are attributed universal significance (for R. Westphal, such a system is ancient, for X. Riemann – the musical beat of the new time). At the same time, the differences between systems are obscured, and what is really common to all systems falls out of sight: rhythm is a schematized rhythm, turned into a stable formula (often traditional and expressed in the form of a set of rules) determined by art. norm, but not psychophysiological. tendencies inherent in human nature in general. Art changes. problems cause the evolution of systems M. Here we can distinguish two main. type.

Antich. the system that gave rise to the term “M.” belongs to the type characteristic of the stage of musical and poetic. unity. M. acts in it in its primary function, subordinating speech and music to general aesthetic. the principle of measure, expressed in the commensurability of time values. The regularity that distinguishes verse from ordinary speech is based on music, and the rules of metrical, or quantitative, versification (except for ancient, as well as Indian, Arabic, etc.), which determine the sequence of long and short syllables without taking into account word stresses, actually serve to insert words in the music scheme, the rhythm of which is fundamentally different from the accent rhythm of new music and can be called quantitative, or time-measuring. Commensurability implies the presence of elementary duration (Greek xronos protos – “chronos protos”, Latin mora – mora) as a unit of measurement of the main. sound (syllabic) durations that are multiples of this elementary value. There are few such durations (there are 5 of them in ancient rhythmics – from l to 5 mora), their ratios are always easily assessed by our perception (in contrast to comparisons of whole notes with thirty-seconds, etc., allowed in the new rhythmics). Main metric the unit – the foot – is formed by a combination of durations, both equal and unequal. Combinations of stops into verses (musical phrases) and verses into stanzas (musical periods) also consist of proportional, but not necessarily equal parts. As a complex system of temporal proportions, in quantitative rhythm, rhythm subdues rhythm to such an extent that it is in ancient theory that its widespread confusion with rhythm is rooted. However, in ancient times these concepts were clearly different, and one can outline several interpretations of this difference that are still relevant today:

1) A clear differentiation of syllables by longitude allowed wok. music does not indicate temporal relationships, which were quite clearly expressed in the poetic text. Muses. rhythm, thus, could be measured by the text (“That speech is quantity is clear: after all, it is measured by a short and long syllable” – Aristotle, “Categories”, M., 1939, p. 14), who himself by itself gave metric. scheme abstracted from other elements of music. This made it possible to single out metrics from the theory of music as the doctrine of verse meters. Hence the opposition between poetic melodicism and musical rhythm that is still encountered (for example, in works on musical folklore by B. Bartok and K. V. Kvitka). R. Westphal, who defined M. as a manifestation of rhythm in speech material, but objected to the use of the term “M.” to music, but believed that in this case it becomes synonymous with rhythm.

2) Antich. rhetoric, which demanded that there be rhythm in prose, but not M., who turns it into verse, testifies to the distinction between speech rhythm and. M. – rhythmic. orderliness that is characteristic of the verse. Such opposition of the correct M. and free rhythm has repeatedly met in modern times (for example, the German name for free verse is freie Rhythmen).

3) In the correct verse, rhythm was also distinguished as a pattern of movement and rhythm as the movement itself that fills this pattern. In antique verse, this movement consisted in accentuation and, in connection with this, in the division of metric. units into ascending (arsis) and descending (thesis) parts (the understanding of these rhythmic moments is greatly hindered by the desire to equate them with strong and weak beats); rhythmic accents are not connected with verbal stresses and are not directly expressed in the text, although their placement undoubtedly depends on the metric. scheme.

4) The gradual separation of poetry from its muses. forms leads already at the turn of cf. centuries to the emergence of a new type of poetry, where not longitude is taken into account, but the number of syllables and the placement of stresses. Unlike the classic “meters”, poems of a new type were called “rhythms”. This purely verbal versification, which reached its full development already in modern times (when poetry in the new European languages, in turn, separated from music), sometimes even now (especially by French authors) is opposed to metric as “rhythmic” (see, for example, Zh. Maruso, Dictionary of linguistic terms, M., 1960, p. 253).

The latter contrapositions lead to definitions that are often found among philologists: M. – the distribution of durations, rhythm – the distribution of accents. Such formulations were also applied to music, but since the time of M. Hauptmann and X. Riemann (in Russia for the first time in the textbook of elementary theory by G. E. Konyus, 1892), the opposite understanding of these terms has prevailed, which is more consistent with rhythmic. I build music and poetry at the stage of their separate existence. “Rhythmic” poetry, like any other, differs from prose in a certain rhythmic way. order, which also receives the name of size or M. (the term is already found in G. de Machaux, 14th century), although it does not refer to the measurement of duration, but to the count of syllables or stresses – purely speech quantities that do not have a specific duration . The role of M. is not in the aesthetic. music regularity as such, but in emphasizing the rhythm and enhancing its emotional impact. Carrying a service function metric. schemes lose their independent aesthetic. interest and become poorer and more monotonous. At the same time, in contrast to the metric verse and contrary to the literal meaning of the word “versification”, a verse (line) does not consist of smaller parts, b.ch. unequal, but divided into equal shares. The name “dolniki”, applied to verses with a constant number of stresses and a varying number of unstressed syllables, could be extended to other systems: in syllabic. each syllable is a “dule” in verses, syllabo-tonic verses, due to the correct alternation of stressed and unstressed syllables, are divided into identical syllabic groups – feet, which should be considered as counting parts, and not as terms. Metric units are formed by repetition, not by comparison of proportional values. Accent M., in contrast to the quantitative one, does not dominate rhythm and gives rise not to the confusion of these concepts, but to their opposition, up to the formulation of A. Bely: rhythm is a deviation from M. (which is associated with the peculiarities of the syllabic-tonic system, where, under certain conditions, the real accentuation deviates from the metric one). Uniform metric the scheme plays a secondary role in verse compared to rhythmic. variety, as evidenced by the emergence of in the 18th century. free verse, where this scheme is absent at all and the difference from prose is only in purely graphic. division into lines, which does not depend on syntax and creates an “installation on M.”.

A similar evolution is taking place in music. Mensural rhythm of the 11th-13th centuries. (the so-called modal), like antique, arises in close connection with poetry (troubadours and trouvers) and is formed by repeating a certain sequence of durations (modus), similar to antique feet (the most common are 3 modes, conveyed here by modern notation: 1- th

, 2nd

and 3rd

). From the 14th century the sequence of durations in music, gradually separating from poetry, becomes free, and the development of polyphony leads to the emergence of ever smaller durations, so that the smallest value of the early mensural rhythmic semibrevis turns into a “whole note”, in relation to which almost all other notes are no longer multiples, but divisors. The “measure” of durations corresponding to this note, marked by hand strokes (Latin mensura), or “measure”, is divided by strokes of lesser force, and so on. to the beginning 17th century there is a modern measure, where the beats, in contrast to the 2 parts of the old measure, one of which could be twice as large as the other, are equal, and there can be more than 2 (in the most typical case – 4). The regular alternation of strong and weak (heavy and light, supporting and non-supporting) beats in the music of modern times creates a meter, or meter, similar to the verse meter—a formal rhythmic beat. scheme, filling in a swarm with a variety of note durations forms a rhythmic. drawing, or “rhythm” in the narrow sense.

A specific musical form of music is tact, which took shape as music separated from related arts. Significant shortcomings of conventional ideas about music. M. stem from the fact that this historically conditioned form is recognized as inherent in music “by nature”. The regular alternation of heavy and light moments is attributed to ancient, medieval music, folklore, etc. peoples. This makes it very difficult to understand not only the music of early eras and muses. folklore, but also their reflections in the music of modern times. In Russian nar. song pl. folklorists use the barline to designate not strong beats (which are not there), but the boundaries between phrases; such “folk beats” (P.P. Sokalsky’s term) are often found in Russian. prof. music, and not only in the form of unusual meters (for example, 11/4 by Rimsky-Korsakov), but also in the form of two-part ones. tripartite, etc. cycles. These are the themes of the finals of the 1st fp. concerto and Tchaikovsky’s 2nd symphony, where the adoption of a barline as a designation of a strong beat leads to a complete distortion of the rhythmic. structures. Bar notation masks a different rhythm. organization and in many dances of West Slavic, Hungarian, Spanish, and other origin (polonaise, mazurka, polka, bolero, habanera, etc.). These dances are characterized by the presence of formulas – a certain sequence of durations (allowing variation within certain limits), edges should not be considered as rhythmic. a pattern that fills the measure, but as a M. of a quantitative type. This formula is similar to the metric foot. versification. In pure dance. East music. peoples formulas can be much more complicated than in verse (see Usul), but the principle remains the same.

Contrasting melodic (accent ratios) with rhythm (length ratios—Riemann), which is inapplicable to quantitative rhythm, also requires amendments in the accent rhythm of modern times. Duration in accent rhythms itself becomes a means of accentuation, which manifests itself both in agogics and in rhythmics. figure, the study of which was started by Riemann. Agogic opportunity. accentuation is based on the fact that when counting beats (which replaced the measurement of time as M.), the inter-shock intervals, conventionally taken as equal, can stretch and shrink within the widest limits. The measure as a certain grouping of stresses, different in strength, does not depend on the tempo and its changes (acceleration, deceleration, fermat), both indicated in the notes and not indicated, and the boundaries of tempo freedom can hardly be established. Formative rhythmic. drawing note durations, measured by the number of divisions per metric. grid regardless of their factual. durations also correspond to the gradation of stress: as a rule, longer durations fall on strong beats, smaller ones on weak beats of the measure, and deviations from this order are perceived as syncopations. There is no such norm in quantitative rhythm; conversely, formulas with an accented short element of the type

(antique iambic, 2nd mode of mensural music),

(ancient anapaest), etc. very characteristic of her.

The “metrical quality” attributed by Riemann to accent ratios belongs to them only by virtue of their normative character. The barline does not indicate an accent, but the normal place of the accent and thus the nature of the real accents, it shows whether they are normal or shifted (syncopes). “Correct” metric. accents is most simply expressed in the repetition of the measure. But besides the fact that the equality of measures in time is by no means respected, there are often changes in size. So, in Scriabin’s poem op. 52 No l for 49 cycles of such changes 42. In the 20th century. “free bars” appear, where there is no time signature and bar lines divide the music into unequal segments. On the other hand, possibly periodic. repetition nonmetric. accents, which do not lose the character of “rhythmic dissonances” (see Beethoven’s large constructions with accents on a weak beat in the finale of the 7th symphony, “crossed” two-beat rhythms in three-beat bars in the 1st part of the 3rd symphony and etc.). At deviations from M. in hl. in voices, in many cases it is preserved in the accompaniment, but sometimes it turns into a series of imaginary shocks, the correlation with which gives the real sound a displaced character.

The “imaginary accompaniment” may be supported by rhythmic inertia, but at the beginning of Schumann’s “Manfred” overture, it stands apart from any relation to the previous and following:

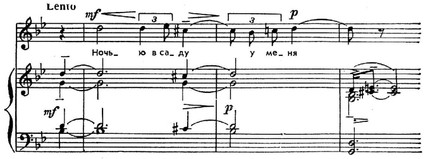

Syncopation the beginning is also possible in free bars:

S. V. Rakhmaninov. Romance “At night in my garden”, op. 38 no 1.

The division into measures in musical notation expresses rhythmic. the intention of the author, and the attempts of Riemann and his followers to “correct” the author’s arrangement in accordance with the real accentuation, indicate a misunderstanding of the essence of M., a mixture of a given measure with a real rhythm.

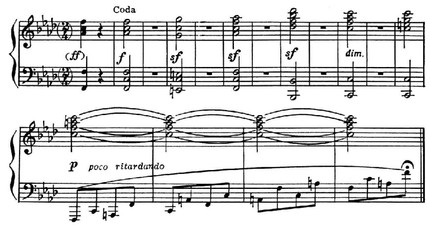

This shift also led (not without the influence of analogies with verse) to the extension of the concept of M. to the structure of phrases, periods, etc. But from all types of poetic music, tact, as a specifically musical music, differs precisely in the absence of metrics. phrasing. In verse, the score of stresses determines the location of verse boundaries, inconsistencies to-rykh with syntactic (enjambements) create in the verse “rhythmic. dissonances.” In music, where M. regulates only accentuation (predetermined places for the end of a period in some dances, for example, in the polonaise, are the legacy of the quantitative M.), enjambements are impossible, but this function is carried out by syncopations, unthinkable in verse (where there is no accompaniment, real or imaginary, which could contradict the accentuation of the main voices). The difference between poetry and music. M. is clearly manifested in the written ways of expressing them: in one case, the division into lines and their groups (stanzas), denoting metric. pauses, in the other – division into cycles, denoting metric. accents. The connection between musical music and accompaniment is due to the fact that a strong moment is taken as the beginning of a metric. units, because it is a normal place for changing harmony, texture, etc. The meaning of bar lines as “skeletal” or “architectural” boundaries was put forward (in a somewhat exaggerated form) by Konus as a counterweight to the syntactic, “covering” articulation, which received the name “metric” in the Riemann school. Catoire also allows for a discrepancy between the boundaries of phrases (syntactic) and “constructions” beginning in the strong tense (“trocheus of the 2nd kind” in his terminology). The grouping of measures in constructions is often subject to a tendency towards “squareness” and the correct alternation of strong and weak measures, reminiscent of the alternation of beats in a measure, but this tendency (psychophysiologically conditioned) is not metric. norm, capable of resisting the muses. syntax that ultimately determines the size of constructions. Still, sometimes small measures are grouped into real metric. unity – “bars of a higher order”, as evidenced by the possibility of syncope. accents on weak measures:

L. Beethoven Sonata for piano, op. 110, part II.

Sometimes authors directly indicate the grouping of bars; in this case, not only square groups (ritmo di quattro battute) are possible, but also three-bars (ritmo di tre battute in Beethoven’s 9th symphony, rythme ternaire in Duke’s The Sorcerer’s Apprentice). To graphic empty measures at the end of the work, ending on a strong measure, are also part of the designations of measures of a higher order, which are frequent among the Viennese classics, but also found later (F. Liszt, “Mephisto Waltz” No1, P. I. Tchaikovsky, finale of the 1st symphony) , as well as the numbering of measures within the group (Liszt, “Mephisto Waltz”), and their countdown begins with a strong measure, and not with syntactic. borders. Fundamental differences between poetic music. M. exclude a direct connection between them in the wok. music of the new age. At the same time, both of them have common features that distinguish them from the quantitative M.: accent nature, auxiliary role and dynamizing function, especially clearly expressed in music, where the continuous clock M. (which arose simultaneously with the “continuous bass”, basso continuo) does not dismember , but, on the contrary, it creates “double bonds” that do not allow music to fall apart into motives, phrases, etc.

References: Sokalsky PP, Russian folk music, Great Russian and Little Russian, in its melodic and rhythmic structure and its difference from the foundations of modern harmonic music, Kharkov, 1888; Konyus G., Supplement to the collection of tasks, exercises and questions (1001) for the practical study of elementary music theory, M., 1896; the same, M.-P., 1924; his own, Criticism of traditional theory in the field of musical form, M., 1932; Yavorsky B., Structure of musical speech Materials and notes, part 2, M., 1908; his own, The Basic Elements of Music, “Art”, 1923, No l (there is a separate print); Sabaneev L., Music of speech Aesthetic research, M., 1923; Rinagin A., Systematics of musical and theoretical knowledge, in the book. De musica Sat. Art., ed. I. Glebova, P., 1923; Mazel L. A., Zukkerman V. A., Analysis of musical works. Elements of muchyka and methods of analysis of small forms, M., 1967; Agarkov O., On the adequacy of perception of the musical meter, in Sat. Musical Art and Science, vol. 1, Moscow, 1970; Kholopova V., Questions of rhythm in the work of composers of the first half of the 1971th century, M., 1; Harlap M., Rhythm of Beethoven, in the book. Beethoven Sat. st., issue. 1971, M., XNUMX. See also lit. at Art. Metrics.

M. G. Harlap