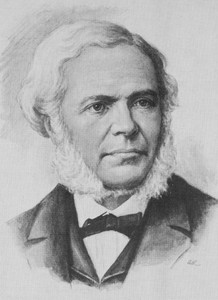

Henryk Szeryng (Henryk Szeryng) |

Henryk Szeryng

Polish violinist who lived and worked in Mexico from the mid-1940s.

Schering studied piano as a child, but soon took up the violin. On the recommendation of the famous violinist Bronislaw Huberman, in 1928 he went to Berlin, where he studied with Carl Flesch, and in 1933 Schering had his first major solo performance: in Warsaw, he performed Beethoven’s Violin Concerto with an orchestra conducted by Bruno Walter. In the same year, he moved to Paris, where he improved his skills (according to Schering himself, George Enescu and Jacques Thibaut had a great influence on him), and also took private lessons in composition from Nadia Boulanger for six years.

At the beginning of World War II, Schering, who was fluent in seven languages, was able to get a position as an interpreter in the “London” government of Poland and, with the support of Wladyslaw Sikorsky, help hundreds of Polish refugees move to Mexico. Fees from numerous (more than 300) concerts he played during the war in Europe, Asia, Africa, America, Schering deducted to help the Anti-Hitler coalition. After one of the concerts in Mexico in 1943, Schering was offered the position of chairman of the department of string instruments at the University of Mexico City. At the end of the war Schering took up his new duties.

After accepting the citizenship of Mexico, for ten years, Schering was engaged almost exclusively in teaching. Only in 1956, at the suggestion of Arthur Rubinstein, the first performance of the violinist in New York after a long break took place, which returned him to world fame. For the next thirty years, until his death, Schering combined teaching with active concert work. He died while on tour in Kassel and is buried in Mexico City.

Shering possessed high virtuosity and elegance of performance, a good sense of style. His repertoire included both classical violin compositions and works by contemporary composers, including Mexican composers, whose compositions he actively promoted. Schering was the first performer of compositions dedicated to him by Bruno Maderna and Krzysztof Penderecki, in 1971 he first performed Niccolo Paganini’s Third Violin Concerto, the score of which was considered lost for many years and was discovered only in the 1960s.

Schering’s discography is very extensive and includes an anthology of violin music by Mozart and Beethoven, as well as concertos by Bach, Mendelssohn, Brahms, Khachaturian, Schoenberg, Bartok, Berg, numerous chamber works, etc. In 1974 and 1975, Schering received the Grammy Award for performance of the piano trios of Schubert and Brahms together with Arthur Rubinstein and Pierre Fournier.

Henryk Schering is one of the performers who consider it one of their most important responsibilities to promote new music from different countries and trends. In a conversation with the Parisian journalist Pierre Vidal, he admitted that, in carrying out this voluntarily undertaken mission, he feels a huge social and human responsibility. After all, he often turns to works of the “extreme left”, “avant-garde”, moreover, belonging to completely unknown or little-known authors, and their fate, in fact, depends on him.

But in order to truly embrace the world of contemporary music, necessary her to study; you need to have deep knowledge, versatile musical education, and most importantly – a “sense of the new”, the ability to understand the most “risky” experiments of modern composers, cutting off the mediocre, only covered with fashionable innovations, and discovering truly artistic, talented. However, this is not enough: “To be an advocate for an essay, one must also love it.” It is quite clear from Schering’s playing that he not only deeply feels and understands new music, but also sincerely loves musical modernity, with all its doubts and searches, breakdowns and achievements.

The violinist’s repertoire in terms of new music is truly universal. Here is the Concert Rhapsody of the Englishman Peter Racine-Frikker, written in the dodecaphonic (“though not very strict”) style; and American Benjamin Lee Concert; and Sequences by the Israeli Roman Haubenstock-Ramati, made according to the serial system; and the Frenchman Jean Martinon, who dedicated the Second Violin Concerto to Schering; and the Brazilian Camargo Guarnieri, who wrote the Second Concerto for Violin and Orchestra especially for Schering; and the Mexicans Sylvester Revueltas and Carlos Chavets and others. Being a citizen of Mexico, Schering does a lot to popularize the work of Mexican composers. It was he who first performed in Paris the violin concerto of Manuel Ponce, who is for Mexico (according to Schering) about the same as Sibelius is for Finland. In order to truly understand the nature of Mexican creativity, he studied the folklore of the country, and not only of Mexico, but of the Latin American peoples as a whole.

His judgments about the musical art of these peoples are extraordinarily interesting. In a conversation with Vidal, he mentions the complex synthesis in Mexican folklore of ancient chants and intonations, dating back, perhaps, to the art of the Maya and the Aztecs, with intonations of Spanish origin; he also feels the Brazilian folklore, highly appreciating its refraction in the work of Camargo Guarnieri. Of the latter, he says that he is “a folklorist with a capital F… as convinced as Vila Lobos, a kind of Brazilian Darius Milho.”

And this is only one of the sides of Schering’s multifaceted performing and musical image. It is not only “universal” in its coverage of contemporary phenomena, but no less universal in its coverage of epochs. Who does not remember his interpretation of Bach’s sonatas and scores for solo violin, which struck the audience with the filigree of voice leading, the classical rigor of figurative expression? And along with Bach, the graceful Mendelssohn and impetuous Schumann, whose violin concerto Schering literally revived.

Or in a Brahms concerto: Schering has neither the titanic, expressionistically condensed dynamics of Yasha Heifetz, nor the spiritual anxiety and passionate drama of Yehudi Menuhin, but there is something from both the first and the second. In Brahms, he occupies the middle between Menuhin and Heifetz, emphasizing in equal measure the classical and romantic principles that are so closely united in this wonderful creation of world violin art.

Makes itself felt in the performing appearance of Schering and his Polish origin. It manifests itself in a special love for national Polish art. He highly appreciates and subtly feels the music of Karol Szymanowski. The second concerto of which is played very often. In his opinion, the Second Concerto is among the best works of this Polish classic – such as “King Roger”, Stabat mater, Symphony Concerto for Piano and Orchestra, dedicated to Arthur Rubinstein.

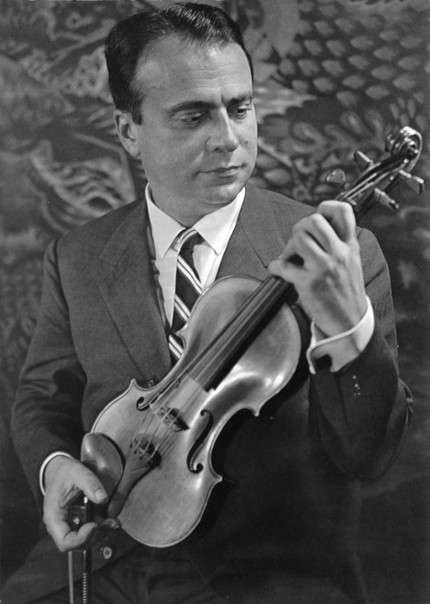

Shering’s playing captivates with richness of colors and perfect instrumentalism. He is like a painter and at the same time a sculptor, dressing each performed work in an irreproachably beautiful, harmonious form. At the same time, in his performance, the “pictorial”, as it seems to us, even somewhat prevails over the “expressive”. But the craftsmanship is so great that it invariably delivers the greatest aesthetic pleasure. Most of these qualities were also noted by Soviet reviewers after Schering’s concerts in the USSR.

He first came to our country in 1961 and immediately won the strong sympathy of the audience. “An artist of the highest class,” was how the Moscow press rated him. “The secret of his charm lies … in the individual, original features of his appearance: in nobility and simplicity, strength and sincerity, in a combination of passionate romantic elation and courageous restraint. Schering has impeccable taste. His timbre palette abounds with colors, but he uses them (as well as his enormous technical capabilities) without ostentatious showiness – elegantly, rigorously, economically.

And further, the reviewer singles out Bach from everything played by the violinist. Yes, indeed, Schering feels the music of Bach extraordinarily deeply. “His performance of Bach’s Partita in D minor for solo violin (the very one that ends with the famous Chaconne) breathed with amazing immediacy. Each phrase was filled with penetrating expressiveness and at the same time included in the flow of melodic development – continuously pulsating, freely flowing. The form of individual pieces was remarkable for its excellent flexibility and completeness, but the whole cycle from play to play, as it were, grew from one grain into a harmonious, unified whole. Only a talented master can play Bach like that.” Noting further the ability for an unusually subtle and lively sense of national color in Manuel Ponce’s “Short Sonata”, in Ravel’s “Gypsy”, Sarasate’s plays, the reviewer asks the question: “Is it not communication with Mexican folk musical life, which has absorbed abundant elements of Spanish folklore, Shering owes that juiciness, convexity and ease of expression with which the plays of Ravel and Sarasate, fairly played on all stages of the world, come to life under his bow?

Schering’s concerts in the USSR in 1961 were an exceptional success. On November 17, when in Moscow in the Great Hall of the Conservatory with the State Symphony Orchestra of the USSR he played three concerts in one program – M. Poncet, S. Prokofiev (No. 2) and P. Tchaikovsky, the critic wrote: “It was a triumph of an unsurpassed virtuoso and inspired artist-creator… He plays simply, at ease, as if jokingly overcomes all technical difficulties. And with all that – the perfect purity of intonation … In the highest register, in the most complex passages, in harmonics and double notes played at a fast pace, the intonation invariably remains crystal clear and flawless and there are no neutral, “dead places” in his performance, everything sounds excitedly, expressively, the frantic temperament of the violinist imperiously conquers with the power that everyone who is under the influence of his playing obeys … ”Shering was unanimously perceived in the Soviet Union as one of the most outstanding violinists of our time.

Schering’s second visit to the Soviet Union took place in the autumn of 1965. The general tone of the reviews remained unchanged. The violinist is again met with great interest. In a critical article published in the September issue of the Musical Life magazine, reviewer A. Volkov compared Schering with Heifetz, noting his similar precision and accuracy of technique and rare beauty of the sound, “warm and very intense (Schering prefers tight bow pressure even in mezzo piano). The critic thoughtfully analyzes Schering’s performance of the violin sonatas and Beethoven’s concerto, believing that he departs from the usual interpretation of these compositions. “To use the well-known expression of Romain Rolland, we can say that the Beethovenian granite channel at Schering has been preserved, and a powerful stream runs swiftly in this channel, but it was not fiery. There was energy, will, efficiency – there was no fiery passion.

Judgments of this kind are easily challenged, because they can always contain elements of subjective perception, but in this case the reviewer is right. Sharing is really a performer of an energetic, dynamic plan. Juiciness, “voluminous” colors, magnificent virtuosity are combined in him with a certain severity of phrasing, enlivened mainly by the “dynamics of action”, and not contemplation.

But still, Schering can also be fiery, dramatic, romantic, passionate, which is clearly manifested in his music by Brahms. Consequently, the nature of his interpretation of Beethoven is determined by fully conscious aesthetic aspirations. He emphasizes in Beethoven the heroic principle and the “classic” ideality, sublimity, “objectivity”.

He is closer to Beethoven’s heroic citizenship and masculinity than the ethical side and the lyricism that, say, Menuhin emphasizes in Beethoven’s music. Despite the “decorative” style, Schering is alien to spectacular variety. And again I want to join Volkov when he writes that “for all the reliability of Schering’s technique”, “brilliance”, incendiary virtuosity is not his element. Schering by no means avoids the virtuoso repertoire, but virtuoso music is really not his forte. Bach, Beethoven, Brahms – this is the basis of his repertoire.

Shering’s playing style is quite impressive. True, in one review it is written: “The artist’s performing style is distinguished primarily by the absence of external effects. He knows many “secrets” and “miracles” of the violin technique, but he does not show them off…” All this is true, and at the same time, Schering has a lot of external plastique. His staging, hand movements (especially the right one) deliver aesthetic pleasure and “for the eyes” – they are so elegant.

Biographical information about Schering is inconsistent. The Riemann Dictionary says that he was born on September 22, 1918 in Warsaw, that he is a student of W. Hess, K. Flesch, J. Thibaut and N. Boulanger. Approximately the same is repeated by M. Sabinina: “I was born in 1918 in Warsaw; studied with the famous Hungarian violinist Flesh and with the famous Thibault in Paris.

Finally, similar data are available in the American magazine “Music and Musicians” for February 1963: he was born in Warsaw, studied piano with his mother from the age of five, but after a few years he switched to the violin. When he was 10 years old, Bronislav Huberman heard him and advised him to send him to Berlin to K. Flesch. This information is accurate, since Flesch himself reports that in 1928 Schering took lessons from him. At the age of fifteen (in 1933) Shering was already prepared for public speaking. With success, he gives concerts in Paris, Vienna, Bucharest, Warsaw, but his parents wisely decided that he was not quite ready yet and should return to classes. During the war, he has no engagements, and he is forced to offer services to the allied forces, speaking at the fronts more than 300 times. After the war, he chose Mexico as his residence.

In an interview with Parisian journalist Nicole Hirsch Schering reports somewhat different data. According to him, he was not born in Warsaw, but in Zhelyazova Wola. His parents belonged to the wealthy circle of the industrial bourgeoisie – they owned a textile company. The war, which was raging at the time when he was to be born, forced the mother of the future violinist to leave the city, and for this reason little Henryk became a countryman of the great Chopin. His childhood passed happily, in a very close-knit family, who was also passionate about music. Mother was an excellent pianist. Being a nervous and exalted child, he instantly calmed down as soon as his mother sat down at the piano. His mother began to play this instrument as soon as his age allowed him to reach the keys. However, the piano did not fascinate him and the boy asked to buy a violin. His wish was granted. On the violin, he began to make such rapid progress that the teacher advised his father to train him as a professional musician. As is often the case, my father objected. For parents, music lessons seemed like fun, a break from the “real” business, and therefore the father insisted that his son continue his general education.

Nevertheless, the progress was so significant that at the age of 13, Henryk performed publicly with the Brahms Concerto, and the orchestra was directed by the famous Romanian conductor Georgescu. Struck by the boy’s talent, the maestro insisted that the concert be repeated in Bucharest and introduced the young artist to court.

The obvious huge success of Henryk forced his parents to change their attitude towards his artistic role. It was decided that Henryk would go to Paris to improve his violin playing. Schering studied in Paris in 1936-1937 and remembers this time with particular warmth. He lived there with his mother; studied composition with Nadia Boulanger. Here again there are discrepancies with the data of the Dictionary of Riemann. He was never a student of Jean Thibault, and Gabriel Bouillon became his violin teacher, to whom Jacques Thibault sent him. Initially, his mother really tried to assign him to the venerable head of the French violin school, but Thibaut refused under the pretext that he was avoiding giving lessons. In relation to Gabriel Bouillon, Schering retained a feeling of deep reverence for the rest of his life. During the first year of his stay in his class at the conservatory, where Schering passed the exams with flying colors, the young violinist went through all the classical French violin literature. “I was soaked in French music to the bone!” At the end of the year, he received the first prize in traditional conservatory competitions.

The Second World War broke out. She found Henryk with his mother in Paris. The mother left for Isère, where she remained until liberation, while the son volunteered for the Polish army, which was being formed in France. In the form of a soldier, he gave his first concerts. After the armistice of 1940, on behalf of the President of Poland Sikorski, Schering was recognized as the official musical “attache” to the Polish troops: “I felt both extremely proud and very embarrassed,” says Schering. “I was the youngest and most inexperienced of the artists who traveled the theaters of war. My colleagues were Menuhin, Rubinshtein. At the same time, I never subsequently experienced a feeling of such complete artistic satisfaction as in that era: we delivered pure joy and opened souls and hearts to music that were previously closed to it. It was then that I realized what role music can play in a person’s life and what power it brings to those who are able to perceive it.”

But grief also came: the father, who remained in Poland, together with close relatives of the family, were brutally murdered by the Nazis. The news of his father’s death shocked Henryk. He did not find a place for himself; nothing more connected him with his homeland. He leaves Europe and heads for the United States. But there fate does not smile at him – there are too many musicians in the country. Fortunately, he was invited to a concert in Mexico, where he unexpectedly received a profitable offer to organize a violin class at the Mexican University and thus lay the foundations of the national Mexican school of violinists. From now on, Schering becomes a citizen of Mexico.

Initially, pedagogical activity absorbs it entirely. He works with students 12 hours a day. And what else is left for him? There are few concerts, no lucrative contracts are expected, since he is completely unknown. Wartime circumstances prevented him from achieving popularity, and big impresarios have nothing to do with a little-known violinist.

Artur Rubinstein made a happy turn in his fate. Upon learning of the arrival of the great pianist in Mexico City, Schering goes to his hotel and asks him to listen. Struck by the perfection of the violinist’s playing, Rubinstein does not let go of him. He makes him his partner in chamber ensembles, performs with him in sonata evenings, they play music for hours at home. Rubinstein literally “opens” Schering to the world. He connects the young artist with his American impresario, through him the gramophone firms conclude the first contracts with Schering; he recommends Schering to the famous French impresario Maurice Dandelo, who helps the young artist organize important concerts in Europe. Schering opens up prospects for concerts all over the world.

True, this did not happen immediately, and Schering was firmly attached to the University of Mexico for some time. Only after Thibault invited him to take the place of a permanent member of the jury in the international competitions named after Jacques Thibault and Marguerite Long, Schering left this post. However, not quite, because he would not have agreed to part completely with the university and the violin class created in it for anything in the world. For several weeks a year, he certainly conducts counseling sessions with students there. Shering is engaged in pedagogy willingly. In addition to the University of Mexico, he teaches at the summer courses of the Academy in Nice founded by Anabel Massis and Fernand Ubradus. Those who have had the opportunity to study or consult Schering invariably speak of his pedagogy with deep respect. In his explanations, one can feel great erudition, excellent knowledge of violin literature.

Schering’s concert activity is very intensive. In addition to public performances, he often plays on the radio and records on records. The big prize for the best recording (“Grand Prix du Disc”) was awarded to him twice in Paris (1955 and 1957).

Sharing is highly educated; he is fluent in seven languages (German, French, English, Italian, Spanish, Polish, Russian), very well-read, loves literature, poetry and especially history. With all his technical skill, he denies the need for prolonged exercise: no more than four hours a day. “Besides, it’s tiring!”

Shering is not married. His family consists of his mother and brother, with whom he spends several weeks each year in Isère or Nice. He is especially attracted by the quiet Ysere: “After my wanderings, I really appreciate the peace of the French fields.”

His main and all-consuming passion is music. She is for him – the whole ocean – boundless and forever alluring.

L. Raaben, 1969