Giovanni Battista Viotti |

Giovanni Battista Viotti

It is difficult now even to imagine what fame Viotti enjoyed during his lifetime. A whole epoch in the development of world violin art is associated with his name; he was a kind of standard by which violinists were measured and evaluated, generations of performers learned from his works, his concertos served as a model for composers. Even Beethoven, when creating the Violin Concerto, was guided by Viotti’s Twentieth Concerto.

An Italian by nationality, Viotti became the head of the French classical violin school, influencing the development of French cello art. To a large extent, Jean-Louis Duport Jr. (1749-1819) came from Viotti, transferring many of the principles of the famous violinist to the cello. Rode, Baio, Kreutzer, students and admirers of Viotti, dedicated the following enthusiastic lines to him in their School: in the hands of great masters acquired a different character, which they wished to give it. Simple and melodic under Corelli’s fingers; harmonious, gentle, full of grace under the bow of Tartini; pleasant and clean at Gavignier’s; grandiose and majestic at Punyani; full of fire, full of courage, pathetic, great in the hands of Viotti, he has reached perfection to express passions with energy and with that nobility that secures the place he occupies and explains the power he has over the soul.

Viotti was born on May 23, 1753 in the town of Fontanetto, near Crescentino, Piedmontese district, in the family of a blacksmith who knew how to play the horn. The son received his first music lessons from his father. The boy’s musical abilities showed up early, at the age of 8. His father bought him a violin at the fair, and young Viotti began to learn from it, essentially self-taught. Some benefit came from his studies with the lute player Giovannini, who settled in their village for a year. Viotti was then 11 years old. Giovannini was known as a good musician, but the short duration of their meeting indicates that he could not give Viotti much especially.

In 1766 Viotti went to Turin. Some flutist Pavia introduced him to the Bishop of Strombia, and this meeting turned out to be favorable for the young musician. Interested in the talent of the violinist, the bishop decided to help him and recommended the Marquis de Voghera, who was looking for a “teaching companion” for his 18-year-old son, Prince della Cisterna. At that time, it was customary in aristocratic houses to take a talented young man into their house in order to contribute to the development of their children. Viotti settled in the prince’s house and was sent to study with the famous Punyani. Subsequently, Prince della Cisterna boasted that Viotti’s training with Pugnani cost him over 20000 francs: “But I do not regret this money. The existence of such an artist could not be paid too dearly.

Pugnani superbly “polished” Viotti’s game, turning him into a complete master. He apparently loved his talented student very much, because as soon as he was sufficiently prepared, he took him with him on a concert trip to the cities of Europe. This happened in 1780. Before the trip, since 1775, Viotti worked in the orchestra of the Turin court chapel.

Viotti gave concerts in Geneva, Bern, Dresden, Berlin and even came to St. Petersburg, where, however, he did not have public performances; he played only at the royal court, presented by Potemkin to Catherine II. The concerts of the young violinist were held with constant and ever-increasing success, and when Viotti arrived in Paris around 1781, his name was already widely known.

Paris met Viotti with a stormy seething of social forces. Absolutism lived out its last years, fiery speeches were uttered everywhere, democratic ideas excited the minds. And Viotti did not remain indifferent to what was happening. He was fascinated by the ideas of the encyclopedists, in particular Rousseau, before whom he bowed for the rest of his life.

However, the worldview of the violinist was not stable; this is confirmed by the facts of his biography. Before the revolution, he performed the duties of a court musician, first with the Prince Gamenet, then with the Prince of Soubise, and finally with Marie Antoinette. Heron Allen quotes Viotti’s loyal statements from his autobiography. After the first performance before Marie Antoinette in 1784, “I decided,” writes Viotti, “to no longer speak to the public and devote myself entirely to the service of this monarch. As a reward, she procured me, during the tenure of Minister Colonna, a pension of 150 pounds sterling.

Viotti’s biographies often contain stories that testify to his artistic pride, which did not allow him to bow before the powers that be. Fayol, for example, reads: “Queen of France Marie Antoinette wished Viotti to come to Versailles. The day of the concert arrived. All the courtiers came and the concert began. The very first bars of the solo aroused great attention, when suddenly a cry was heard in the next room: “Place for Monsignor Comte d’Artois!”. Amidst the confusion that followed, Viotti took the violin in his hand and went out, leaving the whole courtyard, much to the embarrassment of those present. And here is another case, also told by Fayol. He is curious by the manifestation of pride of a different kind – a man of the “third estate”. In 1790, a member of the National Assembly, a friend of Viotti, lived in one of the Parisian houses on the fifth floor. The famous violinist agreed to give a concert at his home. Note that the aristocrats lived exclusively in the lower floors of buildings. When Viotti learned that several aristocrats and high-society ladies were invited to his concert, he said: “We have stooped enough to them, now let them rise to us.”

On March 15, 1782, Viotti first appeared before the Parisian public at an open concert at the Concert spirituel. It was an old concert organization associated mainly with aristocratic circles and the big bourgeoisie. At the time of Viotti’s performance, the Concert spirituel (Spiritual Concert) competed with the “Concerts of Amateurs” (Concerts des Amateurs), founded in 1770 by Gossec and renamed in 1780 into the “Concerts of the Olympic Lodge” (“Concerts de la Loge Olimpique”). A predominantly bourgeois audience gathered here. But still, until its closure in 1796, the “Concert spiriuel” was the largest and world-famous concert hall. Therefore, Viotti’s performance in it immediately attracted attention to him. The director of the Concert spirituel Legros (1739-1793), in an entry dated March 24, 1782, stated that “with the concert held on Sunday, Viotti strengthened the great fame that he had already acquired in France.”

At the height of his fame, Viotti suddenly stopped performing in public concerts. Eimar, the author of Viotti’s Anecdotes, explains this fact by the fact that the violinist treated with contempt the applause of the public, who had little understanding of music. However, as we know from the cited autobiography of the musician, Viotti explains his refusal from public concerts by the duties of the court musician Marie Antoinette, to whose service he decided at that time to devote himself.

However, one does not contradict the other. Viotti was really disgusted by the superficiality of the tastes of the public. By 1785 he was close friends with Cherubini. They settled together at rue Michodière, no. 8; their abode was frequented by musicians and music lovers. In front of such an audience, Viotti played willingly.

On the very eve of the revolution, in 1789, the Count of Provence, the king’s brother, together with Leonard Otier, Marie Antoinette’s enterprising hairdresser, organized the King’s Brother Theatre, inviting Martini and Viotti as directors. Viotti always gravitated toward all kinds of organizational activities and, as a rule, this ended in failure for him. In the Tuileries Hall, performances of Italian and French comic opera, comedy in prose, poetry and vaudeville began to be given. The center of the new theater was the Italian opera troupe, which was nurtured by Viotti, who set to work with enthusiasm. However, the revolution caused the collapse of the theater. Martini “at the most turbulent moment of the revolution was even forced to hide in order to let his connections with the court be forgotten.” Things were no better with Viotti: “Having placed almost everything that I had in the entreprise of the Italian theater, I experienced terrible fear at the approach of this terrible stream. How much trouble I had and what deals I had to make to get out of a predicament! Viotti recalls in his autobiography quoted by E. Heron-Allen.

Until a certain period in the development of events, Viotti apparently tried to hold on. He refused to emigrate and, wearing the uniform of the National Guard, remained with the theater. The theater was closed in 1791, and then Viotti decided to leave France. On the eve of the arrest of the royal family, he fled from Paris to London, where he arrived on July 21 or 22, 1792. Here he was warmly welcomed. A year later, in July 1793, he was forced to go to Italy in connection with the death of his mother and to take care of his brothers, who were still children. However, Riemann claims that Viotti’s trip to his homeland is connected with his desire to see his father, who soon died. One way or another, but outside of England, Viotti was until 1794, having visited during this time not only in Italy, but also in Switzerland, Germany, Flanders.

Returning to London, for two years (1794-1795) he led an intense concert activity, performing in almost all concerts organized by the famous German violinist Johann Peter Salomon (1745-1815), who settled in the English capital from 1781. Salomon’s concerts were very popular.

Among Viotti’s performances, his concert in December 1794 with the famous double bass player Dragonetti is curious. They performed the Viotti duet, with Dragonetti playing the second violin part on the double bass.

Living in London, Viotti again became involved in organizational activities. He took part in the management of the Royal Theatre, taking over the affairs of the Italian Opera, and after the departure of Wilhelm Kramer from the post of director of the Royal Theatre, he succeeded him in this post.

In 1798, his peaceful existence was suddenly broken. He was charged with a police charge of hostile designs against the Directory, which replaced the revolutionary Convention, and that he was in contact with some of the leaders of the French revolution. He was asked to leave England within 24 hours.

Viotti settled in the town of Schoenfeldts near Hamburg, where he lived for about three years. There he intensely composed music, corresponded with one of his closest English friends, Chinnery, and studied with Friedrich Wilhelm Piksis (1786-1842), later a famous Czech violinist and teacher, founder of the school of violin playing in Prague.

In 1801 Viotti received permission to return to London. But he could not get involved in the musical life of the capital and, on the advice of Chinnery, he took up the wine trade. It was a bad move. Viotti proved to be an incapable merchant and went bankrupt. From Viotti’s will, dated March 13, 1822, we learn that he did not pay off the debts that he had formed in connection with the ill-fated trade. He wrote that his soul was torn apart from the consciousness that he was dying without repaying Chinnery’s debt of 24000 francs, which she lent him for the wine trade. “If I die without paying this debt, I ask you to sell everything that only I can find, realize it and send it to Chinnery and her heirs.”

In 1802, Viotti returns to musical activity and, living permanently in London, sometimes travels to Paris, where his playing is still admired.

Very little is known about Viotti’s life in London from 1803 to 1813. In 1813 he took an active part in the organization of the London Philharmonic Society, sharing this honor with Clementi. The opening of the Society took place on March 8, 1813, Salomon conducted, while Viotti played in the orchestra.

Unable to cope with the growing financial difficulties, in 1819 he moved to Paris, where, with the help of his old patron, the Count of Provence, who became King of France under the name of Louis XVIII, he was appointed director of the Italian Opera House. On February 13, 1820, the Duke of Berry was assassinated in the theater, and the doors of this institution were closed to the public. The Italian opera moved several times from one room to another and eked out a miserable existence. As a result, instead of strengthening his financial position, Viotti became completely confused. In the spring of 1822, exhausted by failures, he returned to London. His health is rapidly deteriorating. On March 3, 1824, at 7 o’clock in the morning, he died at the home of Caroline Chinnery.

Little property remained from him: two manuscripts of concertos, two violins – Klotz and a magnificent Stradivarius (he asked to sell the latter to pay off debts), two gold snuffboxes and a gold watch – that’s all.

Viotti was a great violinist. His performance is the highest expression of the style of musical classicism: the game was distinguished by exceptional nobility, pathetic sublimity, great energy, fire, and at the same time strict simplicity; she was characterized by intellectualism, special masculinity and oratorical elation. Viotti had a powerful sound. The masculine rigor of performance was emphasized by a moderate, restrained vibration. “There was something so majestic and inspirational about his performance that even the most skilled performers shied away from him and seemed mediocre,” Heron-Allen writes, quoting Miel.

The performance of Viotti corresponded to his work. He wrote 29 violin concertos and 10 piano concertos; 12 sonatas for violin and piano, many violin duets, 30 trios for two violins and double bass, 7 collections of string quartets and 6 quartets for folk melodies; a number of cello works, several vocal pieces – a total of about 200 compositions.

Violin concertos are the most famous of his legacy. In the works of this genre, Viotti created examples of heroic classicism. The severity of their music is reminiscent of the paintings of David and unites Viotti with such composers as Gossec, Cherubini, Lesueur. The civic motifs in the first movements, the elegiac and dreamy pathos in the adagio, the seething democratism of the final rondos, filled with the intonations of the songs of the Parisian working suburbs, favorably distinguish his concertos from the violin creativity of his contemporaries. Viotti had a generally modest composing talent, but he was able to sensitively reflect the trends of the time, which gave his compositions a musical and historical significance.

Like Lully and Cherubini, Viotti can be considered a true representative of national French art. In his work, Viotti did not miss a single national stylistic feature, the preservation of which was taken care of with amazing zeal by the composers of the revolutionary era.

For many years, Viotti was also engaged in pedagogy, although in general it never occupied a central place in his life. Among his students are such outstanding violinists as Pierre Rode, F. Pixis, Alde, Vache, Cartier, Labarre, Libon, Maury, Pioto, Roberecht. Pierre Baio and Rudolf Kreutzer considered themselves Viotti’s students, despite the fact that they did not take lessons from him.

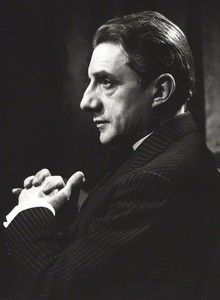

Several images of Viotti have survived. His most famous portrait was painted in 1803 by the French artist Elisabeth Lebrun (1755-1842). Heron-Allen describes his appearance as follows: “Nature generously rewarded Viotti both physically and spiritually. The majestic, courageous head, the face, although not possessing the perfect regularity of features, was expressive, pleasant, radiated light. His figure was very proportionate and graceful, his manners excellent, his conversation lively and refined; he was a skillful narrator and in his transmission the event seemed to come to life again. Despite the atmosphere of decay in which Viotti lived at the French court, he never lost his clear kindness and honest fearlessness.

Viotti completed the development of the violin art of the Enlightenment, combining in his performance and work the great traditions of Italy and France. The next generation of violinists opened a new page in the history of the violin, associated with a new era – the era of romanticism.

L. Raaben