Gertrud Elisabeth Mara (Gertrud Elisabeth Mara) |

Gertrud Elisabeth Mara

In 1765, sixteen-year-old Elisabeth Schmeling dared to give a public concert in her homeland – in the German city of Kassel. She already enjoyed some fame – ten years ago. Elizabeth went abroad as a violin prodigy. Now she returned from England as an aspiring singer, and her father, who always accompanied his daughter as an impresario, gave her a loud advertisement in order to attract the attention of the Kassel court: whoever was going to choose singing as his vocation had to ingratiate himself with the ruler and get into his opera. The Landgrave of Hesse, as an expert, sent the head of his opera troupe, a certain Morelli, to the concert. His sentence read: “Ella canta come una tedesca.” (She sings like a German – Italian.) Nothing could be worse! Elizabeth, of course, was not invited to the court stage. And this is not surprising: German singers were then quoted extremely low. And from whom did they have to adopt such skill so that they could compete with the Italian virtuosos? In the middle of the XNUMXth century, German opera was essentially Italian. All more or less significant sovereigns had opera troupes, invited, as a rule, from Italy. They were attended entirely by Italians, ranging from the maestro, whose duties also included composing music, and ending with the prima donna and the second singer. German singers, if they were attracted, were only for the most recent roles.

It would not be an exaggeration to say that the great German composers of the late Baroque did nothing to contribute to the emergence of their own German opera. Handel wrote operas like an Italian, and oratorios like an Englishman. Gluck composed French operas, Graun and Hasse – Italian ones.

Long gone are those fifty years before and after the beginning of the XNUMXth century, when some events gave hope for the emergence of a national German opera house. At that time, in many German cities, theatrical buildings sprang up like mushrooms after the rain, although they repeated Italian architecture, but served as centers of art, which did not at all blindly copy the Venetian opera. The main role here belonged to the theater on the Gänsemarkt in Hamburg. The city hall of the wealthy patrician city supported composers, most of all the talented and prolific Reinhard Kaiser, and librettists who wrote German plays. They were based on biblical, mythological, adventure and local historical stories accompanied by music. It should, however, be recognized that they were very far from the high vocal culture of the Italians.

The German Singspiel began to develop a few decades later, when, under the influence of Rousseau and the writers of the Sturm und Drang movement, a confrontation arose between refined affectation (hence, Baroque opera) on the one hand, and naturalness and folk, on the other. In Paris, this confrontation resulted in a dispute between buffonists and anti-buffonists, which began as early as the middle of the XNUMXth century. Some of its participants took on roles that were unusual for them – the philosopher Jean-Jacques Rousseau, in particular, took the side of the Italian opera buffa, although in his incredibly popular singspiel “The Country Sorcerer” shook the dominance of the bombastic lyrical tragedy – the opera of Jean Baptiste Lully. Of course, it was not the nationality of the author that was decisive, but the fundamental question of operatic creativity: what has the right to exist – stylized baroque splendor or musical comedy, artificiality or a return to nature?

Gluck’s reformist operas once again tipped the scales in favor of myths and pathos. The German composer entered the world stage of Paris under the banner of the struggle against the brilliant dominance of the coloratura in the name of the truth of life; but things turned out in such a way that its triumph only prolonged the shattered dominance of ancient gods and heroes, castrati and prima donnas, that is, late baroque opera, reflecting the luxury of royal courts.

In Germany, the uprising against it dates back to the last third of the 1776th century. This merit belongs to the initially modest German Singspiel, which was the subject of a purely local production. In 1785, Emperor Joseph II founded the national court theater in Vienna, where they sang in German, and five years later Mozart’s German opera The Abduction from the Seraglio was staged through and through. This was only the beginning, albeit prepared by numerous Singspiel pieces written by German and Austrian composers. Unfortunately, Mozart, a zealous champion and propagandist of the “German national theater”, soon had to turn again to the help of Italian librettists. “If there had been at least one more German in the theater,” he complained in XNUMX, “the theater would have become completely different! This wonderful undertaking will flourish only after we Germans seriously begin to think in German, act in German and sing in German!”

But everything was still very far from that, when in Kassel for the first time the young singer Elisabeth Schmeling performed before the German public, the same Mara who subsequently conquered the capitals of Europe, pushed the Italian prima donnas into the shadow, and in Venice and Turin defeated them with the help of their own weapons. Frederick the Great famously said that he would rather listen to arias performed by his horses than have a German prima donna in his opera. Let us recall that his contempt for German art, including literature, was second only to his contempt for women. What a triumph for Mara that even this king became her ardent admirer!

But he did not worship her as a “German singer”. In the same way, her victories on European stages did not raise the prestige of German opera. For all her life she sang exclusively in Italian and English, and performed only Italian operas, even if their authors were Johann Adolf Hasse, the court composer of Frederick the Great, Karl Heinrich Graun or Handel. When you get acquainted with her repertoire, at every step you come across the names of her favorite composers, whose scores, yellowed from time to time, are gathering dust unclaimed in the archives. These are Nasolini, Gazzaniga, Sacchini, Traetta, Piccinni, Iomelli. She survived Mozart by forty, and Gluck by fifty years, but neither one nor the other did not enjoy her favor. Her element was the old Neapolitan bel canto opera. With all her heart she was devoted to the Italian school of singing, which she considered the only true one, and despised everything that could threaten to undermine the absolute omnipotence of the prima donna. Moreover, from her point of view, the prima donna had to sing brilliantly, and everything else was unimportant.

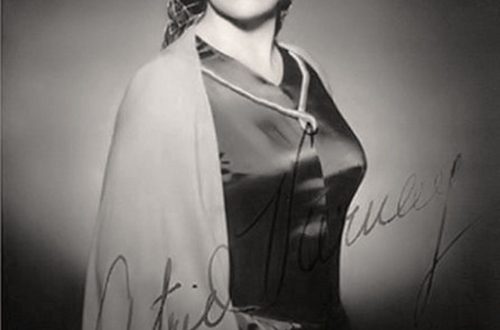

We have received rave reviews from contemporaries about her virtuoso technique (all the more striking that Elizabeth was in the full sense of the self-taught). Her voice, according to the evidence, had the widest range, she sang within more than two and a half octaves, easily taking notes from B of a small octave to F of the third octave; “All tones sounded equally pure, even, beautiful and unconstrained, as if it were not a woman who sang, but a beautiful harmonium played.” Stylish and precise performance, inimitable cadences, graces and trills were so perfect that in England the saying “sings musically like Mara” was in circulation. But nothing out of the ordinary is reported about her acting data. When she was reproached for the fact that even in love scenes she remains calm and indifferent, she only shrugged her shoulders in response: “What am I to do – sing with my feet and hands? I’m a singer. What cannot be done with the voice, I do not. Her appearance was the most ordinary. In ancient portraits, she is depicted as a plump lady with a self-confident face that does not amaze with either beauty or spirituality.

In Paris, the lack of elegance in her clothes was ridiculed. Until the end of her life, she never got rid of a certain primitiveness and German provincialism. Her whole spiritual life was in music, and only in it. And not only in singing; she perfectly mastered the digital bass, comprehended the doctrine of harmony, and even composed music herself. One day Maestro Gazza-niga confessed to her that he could not find a theme for an aria-prayer; the night before the premiere, she wrote the aria with her own hand, to the great pleasure of the author. And to introduce into the arias various coloratura tricks and variations to your taste, bringing them to virtuosity, was generally considered at that time the sacred right of any prima donna.

Mara certainly cannot be attributed to the number of brilliant singers, which was, say, Schroeder-Devrient. If she were Italian, no less fame would fall to her share, but she would remain in the history of the theater only one of many in a series of brilliant prima donnas. But Mara was a German, and this circumstance is of the greatest importance to us. She became the first representative of this people, victoriously breaking through into the phalanx of Italian vocal queens – the first German prima donna of undeniably world class.

Mara lived a long life, almost at the same time as Goethe. She was born in Kassel on February 23, 1749, that is, in the same year as the great poet, and survived him by almost one year. A legendary celebrity of bygone times, she died on January 8, 1833 in Reval, where she was visited by singers on their way to Russia. Goethe repeatedly heard her singing, for the first time when he was a student in Leipzig. Then he admired the “most beautiful singer”, who at that time challenged the palm of beauty from the beautiful Crown Schroeter. However, over the years, surprisingly, his enthusiasm has moderated. But when old friends solemnly celebrated the eighty-twoth anniversary of Mary, the Olympian did not want to stand aside and dedicated two poems to her. Here is the second one:

To Madame Mara To the glorious day of her birth Weimar, 1831

With a song your path has been beaten, All the hearts of the slain; I sang too, inspired Torivshi your way up. I still remember for About the pleasure of singing And I send you hello Like a blessing.

Honoring the old woman by her peers turned out to be one of her last joys. And she was “close to the target”; in art, she achieved everything she could wish for a long time ago, almost until the last days she showed extraordinary activity – she gave singing lessons, and at eighty she entertained guests with a scene from a play in which she played the role of Donna Anna. Her tortuous life path, which led Mara to the highest peaks of glory, ran through the abyss of need, grief and disappointment.

Elisabeth Schmeling was born into a petty-bourgeois family. She was the eighth of ten children of the city musician in Kassel. When at the age of six the girl showed success in playing the violin, Father Schmeling immediately realized that one could benefit from her abilities. At that time, that is, even before Mozart, there was a big fashion for child prodigies. Elizabeth, however, was not a child prodigy, but simply possessed musical abilities, which manifested themselves by chance in playing the violin. At first, the father and daughter grazed at the courts of petty princes, then moved to Holland and England. It was a period of incessant ups and downs, accompanied by minor successes and endless poverty.

Either Father Schmeling was counting on a greater return from singing, or, according to sources, he was really affected by the remarks of some noble English ladies that it was not appropriate for a little girl to play the violin, in any case, from the age of eleven, Elizabeth has been performing exclusively as a singer and a guitarist. Singing lessons – from the famous London teacher Pietro Paradisi – she took only for four weeks: to teach her for free for seven years – and that was exactly what was required in those days for complete vocal training – the Italian, who immediately saw her rare natural data, agreed only on the condition that in the future he will receive deductions from the income of a former student. With this old Schmeling could not agree. Only with great difficulty did they make ends meet with their daughter. In Ireland, Schmeling went to prison – he could not pay his hotel bill. Two years later, misfortune befell them: from Kassel came the news of the death of their mother; after ten years spent in a foreign land, Schmeling was finally about to return to his hometown, but then a bailiff appeared and Schmeling was again put behind bars for debts, this time for three months. The only hope for salvation was a fifteen-year-old daughter. Absolutely alone, she crossed the canal on a simple sailboat, heading to Amsterdam, to old friends. They rescued Schmeling from captivity.

The failures that rained down on the head of the old man did not break his enterprise. It was thanks to his efforts that concert in Kassel took place, at which Elisabeth “sang like a German.” He would undoubtedly continue to involve her in new adventures, but the wiser Elizabeth got out of obedience. She wanted to attend the performances of Italian singers in the court theater, listen to how they sing, and learn something from them.

Better than anyone else, she understood how much she lacked. Possessing, apparently, a huge thirst for knowledge and remarkable musical abilities, she achieved in a few months what others take years of hard work. After performances at minor courts and in the city of Göttingen, in 1767 she took part in the “Great Concerts” by Johann Adam Hiller in Leipzig, which were the forerunners of the concerts in the Leipzig Gewandhaus, and was immediately engaged. In Dresden, the elector’s wife herself took part in her fate – she assigned Elizabeth to the court opera. Interested solely in her art, the girl refused several applicants for her hand. Four hours a day she was engaged in singing, and in addition – the piano, dancing, and even reading, mathematics and spelling, because the childhood years of wandering were actually lost for school education. Soon they started talking about her even in Berlin. The concertmaster of King Friedrich, the violinist Franz Benda, introduced Elisabeth to court, and in 1771 she was invited to Sanssouci. The king’s contempt for German singers (which, by the way, she completely shared) was not a secret for Elizabeth, but this did not prevent her from appearing before the powerful monarch without a shadow of embarrassment, although at that time traits of waywardness and despotism, typical of “Old Fritz”. She easily sang to him from the sheet a bravura aria overloaded with arpeggio and coloratura from Graun’s opera Britannica and was rewarded: the shocked king exclaimed: “Look, she can sing!” He applauded loudly and shouted “bravo”.

That’s when happiness smiled at Elisabeth Schmeling! Instead of “listening to the neighing of her horse”, the king ordered her to perform as the first German prima donna in his court opera, that is, in a theater where until that day only Italians sang, including two famous castrati!

Frederick was so fascinated that old Schmeling, who also acted here as a businesslike impresario for his daughter, managed to negotiate for her a fabulous salary of three thousand thalers (later it was further increased). Elisabeth spent nine years at the Berlin court. Caressed by the king, she already therefore gained wide popularity in all countries of Europe even before she herself visited the musical capitals of the continent. By the grace of the monarch, she became a highly esteemed court lady, whose location was sought by others, but the intrigues inevitable at every court did little to Elizabeth. Neither deceit nor love moved her heart.

You can’t say that she was heavily burdened with her duties. The main one was to sing at the musical evenings of the king, where he himself played the flute, and also to play the main roles in about ten performances during the carnival period. Since 1742, a simple but impressive baroque building typical of Prussia appeared on Unter den Linden – the royal opera, the work of the architect Knobelsdorff. Attracted by Elisabeth’s talent, Berliners “from the people” began to visit this temple of foreign-language art for the nobility more often – in accordance with Friedrich’s clearly conservative tastes, operas were still performed in Italian.

Entrance was free, but the tickets to the theater building were handed out by its employees, and they had to stick it in their hands at least for tea. Places were distributed in strict accordance with ranks and ranks. In the first tier – the courtiers, in the second – the rest of the nobility, in the third – ordinary citizens of the city. The king sat in front of everyone in the stalls, behind him sat the princes. He followed the events on the stage in a lorgnette, and his “bravo” served as a signal for applause. The queen, who lived separately from Frederick, and the princesses occupied the central box.

The theater was not heated. On cold winter days, when the heat emitted by candles and oil lamps was not enough to heat the hall, the king resorted to a tried and tested remedy: he ordered the units of the Berlin garrison to perform their military duty in the theater building that day. The task of the servicemen was utterly simple – to stand in the stalls, spreading the warmth of their bodies. What a truly unparalleled partnership between Apollo and Mars!

Perhaps Elisabeth Schmeling, this star, who rose so rapidly in the theatrical firmament, would have remained until the very moment she left the stage only the court prima donna of the Prussian king, in other words, a purely German actress, if she had not met a man at a court concert in Rheinsberg Castle , who, having first played the role of her lover, and then her husband, became the unwitting culprit of the fact that she received world recognition. Johann Baptist Mara was a favorite of the Prussian prince Heinrich, the king’s younger brother. This native of Bohemia, a gifted cellist, had a disgusting character. The musician also drank and, when drunk, became a rude and bully. The young prima donna, who until then knew only her art, fell in love with a handsome gentleman at first sight. In vain did old Schmeling, sparing no eloquence, try to dissuade his daughter from an inappropriate connection; he achieved only that she parted with her father, without failing, however, to assign him maintenance.

Once, when Mara was supposed to play at court in Berlin, he was found dead drunk in a tavern. The king was furious, and since then the musician’s life has changed dramatically. At every opportunity – and there were more than enough cases – the king plugged Mara into some provincial hole, and once even sent with the police to the fortress of Marienburg in East Prussia. Only the desperate requests of the prima donna forced the king to return him back. In 1773, they married, despite the difference in religion (Elizabeth was a Protestant, and Mara was a Catholic) and despite the highest disapproval of old Fritz, who, as a true father of the nation, considered himself entitled to interfere even in the intimate life of his prima donna. Resigned involuntarily to this marriage, the king passed Elizabeth through the director of the opera so that, God forbid, she would not think of becoming pregnant before the carnival festivities.

Elizabeth Mara, as she was now called, enjoying not only success on the stage, but also family happiness, lived in Charlottenburg in a big way. But she lost her peace of mind. Her husband’s defiant behavior at court and at the opera alienated old friends from her, not to mention the king. She, who had known freedom in England, now felt as if she were in a golden cage. At the height of the carnival, she and Mara tried to escape, but were detained by guards at the city outpost, after which the cellist was again sent into exile. Elizabeth showered her master with heartbreaking requests, but the king refused her in the harshest form. On one of her petitions, he wrote, “She gets paid for singing, not for writing.” Mara decided to take revenge. At a solemn evening in honor of the guest – the Russian Grand Duke Pavel, before whom the king wanted to show off his famous prima donna, she sang deliberately carelessly, almost in an undertone, but in the end vanity got the better of resentment. She sang the last aria with such enthusiasm, with such brilliance, that the thundercloud that had gathered over her head dissipated and the king favorably expressed his pleasure.

Elizabeth repeatedly asked the king to grant her leave for tours, but he invariably refused. Perhaps his instinct told him that she would never return. Inexorable time had bent his back to death, wrinkled his face, now reminiscent of a pleated skirt, made it impossible to play the flute, because arthritic hands no longer obeyed. He began to give up. Greyhounds were dearer to the much aged Friedrich than all people. But he listened to his prima donna with the same admiration, especially when she sang his favorite parts, of course, Italian, for he equated the music of Haydn and Mozart with the worst cat concerts.

Nevertheless, Elizabeth managed in the end to beg for a vacation. She was given a worthy reception in Leipzig, Frankfurt and, what was dearest to her, in her native Kassel. On the way back, she gave a concert in Weimar, which was attended by Goethe. She returned sick to Berlin. The king, in another fit of willfulness, did not allow her to go for treatment in the Bohemian city of Teplitz. This was the last straw that overflowed the cup of patience. The Maras finally decided to make an escape, but acted with the utmost caution. Nevertheless, unexpectedly, they met Count Brühl in Dresden, which plunged them into indescribable horror: is it possible that the almighty minister will inform the Prussian ambassador about the fugitives? They can be understood – before their eyes stood the example of the great Voltaire, who a quarter of a century ago in Frankfurt was detained by the detectives of the Prussian king. But everything turned out well, they crossed the saving border with Bohemia and arrived in Vienna through Prague. Old Fritz, having learned about the escape, at first went on a rampage and even sent a courier to the Vienna court demanding the return of the fugitive. Vienna sent a reply, and a war of diplomatic notes began, in which the Prussian king unexpectedly quickly laid down his arms. But he did not deny himself the pleasure of speaking about Mara with philosophical cynicism: “A woman who completely and completely surrenders to a man is likened to a hunting dog: the more she is kicked, the more devotedly she serves her master.”

At first, devotion to her husband did not bring Elizabeth much luck. The Vienna court accepted the “Prussian” prima donna rather coldly, only the old Archduchess Marie-Theresa, showing cordiality, gave her a letter of recommendation to her daughter, the French Queen Marie Antoinette. The couple made their next stop in Munich. At this time, Mozart staged his opera Idomeneo there. According to him, Elizabeth “did not have the good fortune to please him.” “She does too little to be like a bastard (that’s her role), and too much to touch the heart with good singing.”

Mozart was well aware that Elisabeth Mara, for her part, did not rate his compositions very highly. Perhaps this influenced his judgment. For us, something else is much more important: in this case, two eras alien to each other collided, the old one, which recognized the priority in the opera of musical virtuosity, and the new one, which demanded the subordination of music and voice to dramatic action.

The Maras gave concerts together, and it happened that a handsome cellist was more successful than his inelegant wife. But in Paris, after a performance in 1782, she became the uncrowned queen of the stage, on which the owner of the contralto Lucia Todi, a native Portuguese, had previously reigned supreme. Despite the difference in voice data between the prima donnas, a sharp rivalry arose. Musical Paris for many months was divided into Todists and Maratists, fanatically devoted to their idols. Mara proved herself so wonderful that Marie Antoinette awarded her the title of the first singer of France. Now London also wanted to hear the famous prima donna, who, being German, nevertheless sang divinely. No one there, of course, remembered the beggar girl who exactly twenty years ago had left England in despair and returned to the Continent. Now she is back in a halo of glory. The first concert at the Pantheon – and she has already won the hearts of the British. She was accorded honors such as no singer had known since the great prima donnas of the Handel era. The Prince of Wales became her ardent admirer, most likely conquered not only by the high skill of singing. She, in turn, like nowhere else, felt at home in England, not without reason it was easiest for her to speak and write in English. Later, when the Italian opera season began, she also sang at the Royal Theater, but her greatest success was brought by concert performances that Londoners will remember for a long time. She performed mainly the works of Handel, whom the British, having slightly changed the spelling of his surname, ranked among domestic composers.

The twenty-fifth anniversary of his death was a historic event in England. The celebrations on this occasion lasted three days, their epicenter was the presentation of the oratorio “Messiah”, which was attended by King George II himself. The orchestra consisted of 258 musicians, a choir of 270 people stood on the stage, and above the mighty avalanche of sounds they produced, the voice of Elizabeth Mara, unique in its beauty, rose up: “I know my savior is alive.” The empathetic British came to a real ecstasy. Subsequently, Mara wrote: “When I, putting my whole soul into my words, sang about the great and holy, about what is eternally valuable to a person, and my listeners, filled with trust, holding their breath, empathizing, listened to me, I seemed to myself a saint” . These undeniably sincere words, written at an advanced age, amend the initial impression that can easily be formed from a cursory acquaintance with Mara’s work: that she, being able to master her voice phenomenally, was content with the superficial brilliance of the court bravura opera and did not want anything else. It turns out she did! In England, where for eighteen years she remained the only performer of Handel’s oratorios, where she sang Haydn’s “Creation of the World” in an “angelic way” – this is how one enthusiastic vocal connoisseur responded – Mara turned into a great artist. The emotional experiences of an aging woman, who knew the collapse of hopes, their rebirth and disappointment, certainly contributed to the strengthening of the expressiveness of her singing.

At the same time, she continued to be a prosperous “absolute prima donna”, the favorite of the court, who received unheard-of fees. However, the greatest triumphs awaited her in the very homeland of bel canto, in Turin – where the king of Sardinia invited her to his palace – and in Venice, where from the very first performance she demonstrated her superiority over the local celebrity Brigida Banti. Opera lovers, inflamed by Mara’s singing, honored her in the most unusual way: as soon as the singer finished the aria, they showered the stage of the San Samuele theater with a hail of flowers, then brought her oil-painted portrait to the ramp, and with torches in their hands, led the singer through the crowds of jubilant spectators expressing their delight with loud cries. It must be assumed that after Elizabeth Mara arrived in revolutionary Paris on her way to England in 1792, the picture she saw haunted her relentlessly, reminding her of the fickleness of happiness. And here the singer was surrounded by crowds, but crowds of people who were in a state of frenzy and frenzy. On the New Bridge, her former patroness Marie Antoinette was brought past her, pale, in prison robes, met with hooting and abuse from the crowd. Bursting into tears, Mara recoiled in horror from the carriage window and tried to leave the rebellious city as soon as possible, which was not so easy.

In London, her life was poisoned by the scandalous behavior of her husband. A drunkard and rowdy, he compromised Elizabeth with his antics in public places. It took years and years for her to stop finding an excuse for him: the divorce took place only in 1795. Either as a result of disappointment with an unsuccessful marriage, or under the influence of a thirst for life that flared up in an aging woman, but long before the divorce, Elizabeth met with two men who were almost like her sons.

She was already in her forty-second year when she met a twenty-six-year-old Frenchman in London. Henri Buscarin, the offspring of an old noble family, was her most devoted admirer. She, however, in a kind of blindness, preferred to him a flutist named Florio, the most ordinary guy, moreover, twenty years younger than her. Subsequently, he became her quartermaster, performed these duties until her old age and made good money on it. With Buscaren, she had an amazing relationship for forty-two years, which was a complex mixture of love, friendship, longing, indecision and hesitation. The correspondence between them ended only when she was eighty-three years old, and he – finally! – started a family on the remote island of Martinique. Their touching letters, written in the style of a late Werther, produce a somewhat comical impression.

In 1802, Mara left London, which with the same enthusiasm and gratitude said goodbye to her. Her voice almost did not lose its charm, in the autumn of her life she slowly, with self-esteem, descended from the heights of glory. She visited the memorable places of her childhood in Kassel, in Berlin, where the prima donna of the long-dead king was not forgotten, attracted thousands of listeners to a church concert in which she took part. Even the inhabitants of Vienna, which once received her very coolly, now fell at her feet. The exception was Beethoven – he was still skeptical of Mara.

Then Russia became one of the last stations on her life path. Thanks to her big name, she was immediately accepted at the St. Petersburg court. She no longer sang in the opera, but performances in concerts and at dinner parties with nobles brought such income that she significantly increased her already significant fortune. At first she lived in the capital of Russia, but in 1811 she moved to Moscow and energetically engaged in land speculation.

Evil fate prevented her from spending the last years of her life in splendor and prosperity, earned by many years of singing on various stages of Europe. In the fire of the Moscow fire, everything that she had perished, and she herself had to flee again, this time from the horrors of war. In one night, she turned, if not into a beggar, but into a poor woman. Following the example of some of her friends, Elizabeth proceeded to Revel. In an old provincial town with crooked narrow streets, proud only of its glorious Hanseatic past, there was nevertheless a German theater. After connoisseurs of vocal art from among eminent citizens realized that their town had been made happy by the presence of a great prima donna, the musical life in it unusually revived.

Nevertheless, something prompted the old woman to move from her familiar place and embark on a long journey thousands and thousands of miles, threatening all sorts of surprises. In 1820, she stands on the stage of the Royal Theater in London and sings Guglielmi’s rondo, an aria from Handel’s oratorio “Solomon”, Paer’s cavatina – this is seventy-one years old! A supportive critic praises her “nobility and taste, beautiful coloratura and inimitable trill” in every way, but in reality she, of course, is only a shadow of the former Elisabeth Mara.

It was not a late thirst for fame that prompted her to make a heroic move from Reval to London. She was guided by a motive that seems quite unlikely, given her age: filled with longing, she is looking forward to the arrival of her friend and lover Bouscaren from distant Martinique! Letters fly back and forth, as if obeying someone’s mysterious will. “Are you free too? he asks. “Do not hesitate, dear Elizabeth, to tell me what your plans are.” Her answer has not reached us, but it is known that she was waiting for him in London for more than a year, interrupting her lessons, and only after that, on her way home to Revel, stopping in Berlin, she learned that Buscarin had arrived in Paris.

But it’s too late. Even for her. She hurries not into the arms of her friend, but to blissful loneliness, to that corner of the earth where she felt so good and calm – to Revel. Correspondence, however, continued for another ten years. In his last letter from Paris, Buscarin reports that a new star has risen on the operatic horizon – Wilhelmina Schroeder-Devrient.

Elisabeth Mara died shortly thereafter. A new generation has taken its place. Anna Milder-Hauptmann, Beethoven’s first Leonore, who paid tribute to the former prima donna of Frederick the Great when she was in Russia, has now become a celebrity herself. Berlin, Paris, London applauded Henrietta Sontag and Wilhelmine Schroeder-Devrient.

No one was surprised that German singers became great prima donnas. But Mara paved the way for them. She rightfully owns the palm.

K. Khonolka (translation — R. Solodovnyk, A. Katsura)