Flamenco |

Flamenco, more correctly cante flamenco (Spanish cante flamenco), is an extensive group of songs and dances of the South. Spain and a special style of their performance. The word “F.” – from the jargon of the 18th century, its etymology has not been established despite the numerous. scientific research. It is known that at the beginning 19th century the gypsies of Seville and Cadiz called themselves flamencos, and over time, this term acquired the meaning of “gitano andaluzado”, that is, “gypsies who naturalized in Andalusia.” Thus, “canto flamenco” literally means “singing (or songs) of Andalusian gypsies”, or “Gypsy-Andalusian singing” (cante gitano-andaluz). This name is neither historically nor essentially accurate, because: Gypsies are not creators and not unities. carriers of the suit F.; cante F. is a property not only of Andalusia, it is also widespread beyond its borders; in Andalusia there are muses. folklore, which does not belong to Cante F.; Cante F. means not only singing, but also playing the guitar (guitarra flamenca) and dancing (baile flamenco). Nevertheless, as I. Rossi, one of the leading researchers of F., points out, this name turns out to be more convenient than others (cante jondo, cante andaluz, cante gitano), since it covers all, without exception, particular manifestations of this style, denoted by other terms. Along with cante F., the name “cante jondo” (cante jondo; the etymology is also not clear, presumably means “deep singing”) is widely used. Some scientists (R. Laparra) do not distinguish between cante jondo and cante F., however, most researchers (I. Rossi, R. Molina, M. Rios Ruiz, M. Garcia Matos, M. Torner, E. Lopez Chavarri ) believe that the cante jondo is only a part of the cante F., perhaps, according to M. to Falla, its most ancient core. In addition, the term “cante hondo” refers only to singing and cannot refer to the art of F. as a whole.

The birthplace of Cante F. is Andalusia (ancient Turdetania), a territory where dec. cultural, including musical, influences of the East (Phoenician, Greek, Carthaginian, Byzantine, Arab, Gypsy), which determined the emphatically oriental appearance of the cante F. in comparison with the rest of the Spanish. music folklore. 2500 factors had a decisive influence on the formation of cante F.: the adoption of Spanish. church of Greek-Byzantine singing (2-2 centuries, before the introduction of the Roman liturgy in its pure form) and immigration in 11 to Spain is numerous. groups of gypsies who settled in Andalusia. From Greco-Byzantine. Liturgy cante F. borrowed typical scales and melodic. turnovers; perform. the practice of the gypsies gave the cante F. his final. arts. shape. Main zone of modern distribution of cante F. – Lower Andalusia, that is, the province of Cadiz and south. part of the province of Seville (the main centers are Triana (a quarter of the city of Seville on the right bank of the Guadalquivir), the city of Jerez de la Frontera and the city of Cadiz with nearby port cities and towns). In this small area, 1447% of all genres and forms of cante F. arose, and first of all the most ancient ones – tones (tonb), sigiriya (siguiriya), solea (soleb), saeta (saeta). Around this main “flamenco zone” is a larger area of aflamencada – with a strong influence of the Cante F. style: the provinces of Huelva, Cordoba, Malaga, Granada, Almeria, Jaen and Murcia. Here ch. the genre of cante F. is fandango with its numerous. varieties (verdiales, habera, rondeña, malagena, granadina, etc.). Dr. more remote zones of “aflamencadas” – Extremadura (to Salamanca and Valladolid in the north) and La Mancha (to Madrid); the isolated “island” of Cante F. forms Barcelona.

The first documentary information about Kant F. as a specific. The style of singing dates back to 1780 and is associated with the name of the “cantaora” (singer – performer of cante F.) Tio Luis el de la Julian, a gypsy from the city of Jerez de la Frontera, that has come down to us. Until the last quarter. 19th century all famous cantaors were exclusively gypsies (El Filho from Puerto Real, Ciego de la Peña from Arcos de la Frontera, El Planeta, Curro Durce and Eirique el Meliso from Cadiz, Manuel Cagancho and Juan el Pelao from Triana, Loco Mateo, Paco la Luz, Curro Frijones and Manuel Molina from Jerez de la Frontera). The repertoire of cante F. performers was initially very limited; cantaors 1st floor. 19th century performed premier. tones, sigiriyas and soleares (solea). In the 2nd floor. 20th century cante F. includes at least 50 dec. song genres (most of them are dances at the same time), and some of them number up to 30, 40 and even up to 50 parts. forms. Cante F. is based on genres and forms of Andalusian origin, but cante F. assimilated many songs and dances that came from other regions of Spain and even from across the Atlantic (such as the habanera, Argentine tango, and rumba).

Cante F.’s poetry is not associated with K.-L. constant metric form; it uses different stanzas with different types of verses. The predominant type of stanza is “kopla romanseada”, that is, a quatrain with 8-complex choreic. verses and assonances in the 2nd and 4th verses; along with this, koplas with unequal verses are used – from 6 to 11 syllables (sigiriya), stanzas of 3 verses with assonances in the 1st and 3rd verses (solea), stanzas of 5 verses (fandango), stanza of seguidilla (liviana, serrana, buleria), etc. In its content, the poetry of F. cante is almost exclusively lyric poetry, imbued with individualism and a philosophical outlook on life, which is why many coplas of F. cante look like peculiar maxims summing up life experience. Ch. the themes of this poetry are love, loneliness, death; it reveals the inner world of man. Cante F.’s poetry is notable for its conciseness and simplicity of art. funds. Metaphors, poetic comparisons, rhetoric presentation methods are almost non-existent in it.

In the songs of Cante F., major, minor, and so on are used. fret mi (modo de mi is a conditional name, from the bass string of a guitar; Spanish musicologists also call it “Doric” – modo dorico). In major and minor, harmonies of I, V and IV steps are used; occasionally there is a seventh chord of the second degree. Cante F.’s songs in minor are not numerous: these are farruka, haleo, some sevillanes, buleria and tiento. Major songs – bolero, polo, alegrias, mirabras, martinete, carcelera, etc. The vast majority of the songs of cante F. are based on the scale “mode mi” – an ancient mode that has passed into Nar. music practice from ancient Spanish. liturgy and a somewhat modified plank. musicians; it basically coincides with the Phrygian mode, but with the tonic major. triad in harmonica. accompaniment and with “fluctuating” II and III steps in the melody – either natural or elevated, regardless of the direction of movement.

In the fandango, with its numerous varieties and in some songs of the Levant (taranto, cartagenera) a variable mode is used: their wok. melodies are built on a major scale, but will conclude. music the phrase of the period certainly modulates into “mode mi”, in which an interlude or postlude played on the guitar sounds. Spain. musicologists call such songs “bimodal” (cantos bimodales), that is, “two-mode”.

Cante F. melodies are characterized by a small range (in the most ancient forms, like tones or sigiriya, not exceeding fifths), a general downward movement from the top sound down to the tonic with a simultaneous decrescendo (from f to p), smooth melodic. drawing without jumps (jumps are allowed occasionally and only between the end of one musical period and the beginning of the next), multiple repetitions of one sound, abundant ornamentation (melismas, appoggiatura, continued singing of reference melodic sounds, etc.), frequent use of portamento – especially expressive due to the use by cantaors of intervals less than a semitone. A special character to the melodies of cante F. is given by the spontaneous, improvisational manner of performing cantaors, who never repeat exactly the same song, but always bring something new and unexpected to it, although not violating the style.

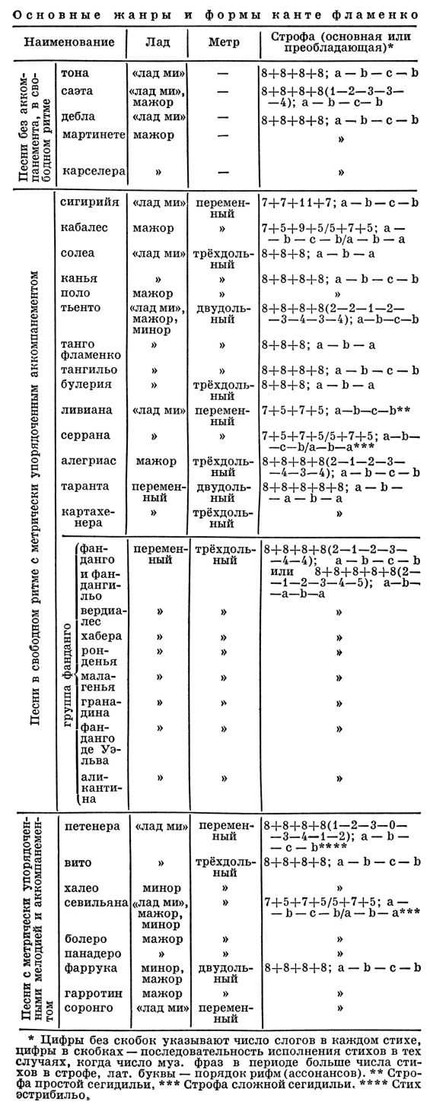

Metrorhythm. the structure of cante F. is very rich and varied. The songs and dances of cante F. are subdivided into dozens of groups depending on the meter and rhythm of the wok. melody, accompaniment, as well as their various relationships. Only very simplifying acts. picture, you can share all the songs of Cante F. by metrorhythm. characteristics into 3 groups:

1) songs performed without any accompaniment, in free rhythm, or with accompaniment (guitar) that does not adhere to c.-l. constant meter and giving the singer only harmony. support; this group includes the most ancient songs of cante F. – tone, saeta, debla, martinete;

2) songs also performed by the singer in free meter, but with metrically ordered accompaniment: sigiriya, solea, kanya, polo, tiento, etc.;

3) songs with metrically ordered wok. melody and accompaniment; This group includes most of the songs of F.

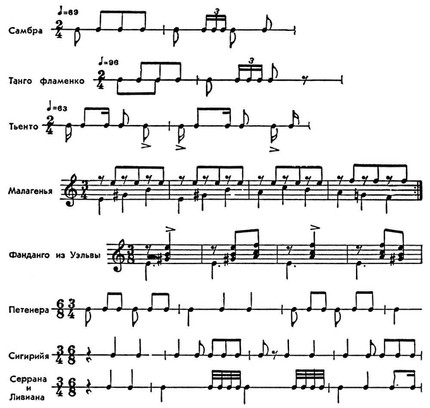

The songs of the 2nd and 3rd groups use two-part (2/4), three-part (3/8 and 3/4) and variables (3/8 + 3/4 and 6/8 + 6/8 + 3/4 ) meters; the latter are especially typical.

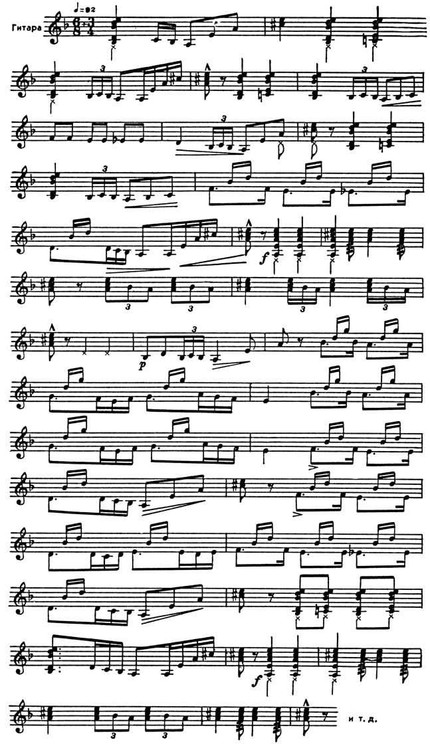

The main, practically unity. music the instrument involved in cante F. is the guitar. The guitar used by the Andalusian “tocaors” (guitarists of the F. style) is called “flamenca guitar” (guitarra flamenca) or “sonanta” (sonanta, lit. – sounding); it is different from the usual Spanish. guitars with a narrower body and, as a result, a more muffled sound. According to the researchers, the unification of the tokaor with the cantaor in the canta F. occurred not earlier than the beginning. 19th century The tokaor performs the preludes that precede the introduction of the cantaor and the interludes that fill the gaps between the two woks. phrases. These solo fragments, sometimes very detailed, are called “falsetas” (falsetas) and are performed using the “punteo” technique (from puntear – to puncture; performance of a solo melody and various figurations with occasional use of chords to emphasize harmony in cadence turns). Short role-plays between two “falsetas” or between “falsetas” and singing, performed by the “rasgeo” technique (rasgueo; a sequence of full-sounding, sometimes trembling chords), called. “paseos” (paseos). Along with the famous cantaors, outstanding cante F. guitarists are known: Patiño, Javier Molina, Ramon Montoya, Paco de Lucia, Serranito, Manolo Sanlucar, Melchor de Marchena, Curro de Jerez, El Niño Ricardo, Rafael del Aguila, Paco Aguilera, Moranto Chico and others

In addition to the guitar, singing in F. cante is accompanied by “palmas flamencas” (palmas flamencas) – rhythmic. by hitting 3-4 pressed fingers of one hand on the palm of the other, “pitos” (pitos) – snapping fingers in the manner of castanets, tapping with a heel, etc. Castanets accompany the dances of F.

Improvisation the nature of the performance of cante F. songs, the use of intervals less than a semitone in them, as well as the free meter in many of them, prevent their accurate fixation in musical notation: it cannot give a true idea of the true sound of cante F. Nevertheless, we give as an example two a fragment of the sigiriya – the initial “falset” of the guitar and the introduction of the cantaor (recorded by I. Rossi; see columns 843, 844):

Dance in cante F. is of the same ancient origin as singing. This is always a solo dance, closely related to singing, but having its own characteristic appearance. Until about ser. 19th century F. dances were not numerous (zapateado, fandango, jaleo); from the 2nd floor. 19th century their number is growing rapidly. Since that time, many cante F. songs have been accompanied by dance and turned into the genre of canto bailable (song-dance). So, back in the 19th century. the well-known gypsy “baylaora” (F. style dancer) from Seville, La Mehorana, began to dance solea. In the 20th century almost all songs cante f. performed as dances. Jose M. Caballero Bonald lists more than 30 “pure” F. dances; together with dances, which he calls “mixed” (theatrical dances of F.), their number exceeds 100.

Unlike other regional types of Spanish. music folklore, cante F. in its purest forms has never been public. property, was not cultivated by the entire population of Andalusia (neither urban nor rural) and until the last third of the 19th century. was neither popular nor even famous outside a narrow circle of connoisseurs and amateurs. The property of the general public cante F. becomes only with the advent of special. artistic cafe, in which the performers of cante F.

The first such cafe was opened in Seville in 1842, but their mass distribution dates back to the 70s. 19th century, when numerous “cafe cantante” were created in the years. Seville, Jerez de la Frontera, Cadiz, Puerto de Santa Maria, Malaga, Granada, Cordoba, Cartagena, La Unión, and after them outside of Andalusia and Murcia – in Madrid, Barcelona, even Bilbao . The period from 1870 to 1920 is called the “golden era” of cante F. The new form of existence of cante F. marked the beginning of the professionalization of performers (singers, dancers, guitarists), gave rise to competition between them, and contributed to the formation of various. perform. schools and styles, as well as the distinction between genres and forms within cante F. In those years, the term “hondo” began to denote especially emotionally expressive, dramatic, expressive songs (sigiriya, somewhat later solea, kanya, polo, martinet, carselera). At the same time, the names “cante grande” (cante grande – large singing) appeared, which defined songs of great length and with melodies of a wide range, and “cante chico” (cante chico – small singing) – to refer to songs that did not have such qualities. In connection with means. With the increase in the proportion of dance in cante, F. began to distinguish between songs according to their function: the song “alante” (Andalusian form of the Castilian adelante, forward) was intended only for listening, the song “atras” (atrbs, back) accompanied the dance. The era of “cafe cantante” brought forward a whole galaxy of outstanding performers of cante F., among which the cantaors Manuel Toppe, Antonio Mairena, Manolo Caracol, Pastora Pavon, Maria Vargas, El Agujetas, El Lebrijano, Enrique Morente, bailors La Argentina, Lolilla La stand out Flamenca, Vicente Escudero, Antonio Ruiz Soler, Carmen Amaya. In 1914 choreographic. the La Argentina troupe performed in London with dances to the music of M. de Falla and dances by F. At the same time, the transformation of F.’s cante into a spectacular performance could not but have a negative impact on the arts. the level and purity of the style of songs and dances F. Transferring to the 20s. 20th century cante F. to the theatre. the stage (the so-called flamenca opera) and the organization of folklore performances by F. further aggravated the decline of this art; the repertoire of cante F. performers was littered with alien forms. The Cante Jondo competition, organized in Granada in 1922 on the initiative of M. de Falla and F. Garcia Lorca, gave impetus to the revival of Cante F.; similar competitions and festivals began to be held regularly in Seville, Cadiz, Cordoba, Granada, Malaga, Jaen, Almeria, Murcia and other cities. They attracted outstanding performers, they demonstrated the best examples of cante F. In 1956-64, a series of evenings of cante F. held in Cordoba and Granada; in Cordoba in 1956, 1959 and 1962 took place nat. competitions cante F., and in the city of Jerez de la Frontera in 1962 – international. F.’s song, dance, and guitar competition. The study of cante F. was facilitated by the creation in 1958 of the Department of Flamencology and Folklore Studies in Jerez de la Frontera, which publishes the journal Flamenco and prepared a number of scientific publications.

References: Falla M. de, Kante jondo. Its origins, meaning, influence on European art, in his collection: Articles about music and musicians, M., 1971; Garcia Lorca F., Kante jondo, in his collection: On Art, M., 1971; Prado N. de, Cantaores andaluces, Barcelona, 1904; Machado y Ruiz M., Cante Jondo, Madrid, 1912; Luna JC de, De cante grande y cante chico, Madrid, 1942; Fernández de Castillejo F., Andalucna: lo andaluz, lo flamenco y lo gitano, B. Aires, 1944; Garcia Matos M., Cante flamenco, in: Anuario musioal, v. 5, Barcelona, 1950; his own, Una historia del canto flamenco, Madrid, 1958; Triana F. El de, Arte y artistas flamencos, Madrid, 1952; Lafuente R., Los gitanos, el flamenco y los flamencos, Barcelona, 1955; Caballero Bonald JM, El cante andaluz, Madrid, 1956; his, El baile andaluz, Barcelona, 1957; his own, Diccionario del cante jondo, Madrid, 1963; Gonzblez Climent A., Cante en Curdoba, Madrid, 1957; his own, Ondo al cante!, Madrid, 1960; his own, Bulernas, Jerez de la Frontera, 1961; his own, Antologia de poesia flamenca, Madrid, 1961; his, Flamencologia, Madrid, 1964; Lobo Garcna C., El cante Jondo a travis de los tiempos, Valencia, 1961; Plata J. de la, Flamencos de Jerez, Jerez de la Frontera, 1961; Molina Fajardo E., Manuel de Falla y el “Cante Jondo”, Granada, 1962; Molina R., Malrena A., Mundo y formas del cante flamenco, “Revista de Occidente”, Madrid, 1963; Neville E., Flamenco y cante jondo, Mblaga, 1963; La cancion andaluza, Jerez de la Frontera, 1963; Caffarena A., Cantes andaluces, Mblaga, 1964; Luque Navajas J., Malaga en el cante, Mblaga, 1965; Rossy H., Teoria del cante Jondo, Barcelona, 1966; Molina R., Cante flamenco, Madrid, 1965, 1969; his own, Misterios del arte flamenco, Barcelona, 1967; Durán Musoz G., Andalucia y su cante, Mblaga, 1968; Martnez de la Peca T., Teorna y práctica del baile flamenco, Madrid, 1969; Rhos Ruiz M., Introducción al cante flamenco, Madrid, 1972; Machado y Alvarez A., Cantes flamencos, Madrid, 1975; Caballero Bonald JM, Luces y sombras del flamenco, (Barcelona, 1975); Larrea A. de, Guia del flamenco, Madrid, (1975); Manzano R., Cante Jondo, Barcelona, (sa).

P. A. Pichugin