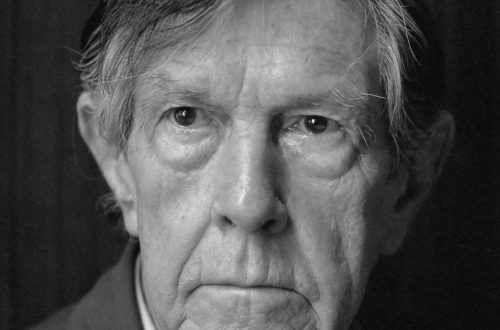

Felix Weingartner |

Felix Weingartner

Felix Weingartner, one of the world’s greatest conductors, occupies a special place in the history of the art of conducting. Having begun his artistic activity at a time when Wagner and Brahms, Liszt and Bülow were still living and creating, Weingartner completed his journey already in the middle of our century. Thus, this artist became, as it were, a link between the old conducting school of the XNUMXth century and modern conducting art.

Weingartner comes from Dalmatia, he was born in the town of Zadar, on the Adriatic coast, in the family of a postal employee. The father died when Felix was still a child, and the family moved to Graz. Here, the future conductor began to study music under the guidance of his mother. In 1881-1883, Weingartner was a student at the Leipzig Conservatory in composition and conducting classes. Among his teachers are K. Reinecke, S. Jadasson, O. Paul. In his student years, the young musician’s conducting talent first manifested itself: in a student concert, he brilliantly performed Beethoven’s Second Symphony as a keepsake. This, however, brought him only the reproach of Reinecke, who did not like such self-confidence of the student.

In 1883, Weingartner made his independent debut in Königsberg, and a year later his opera Shakuntala was staged in Weimar. The author himself spent several years here, becoming a student and friend of Liszt. The latter recommended him as an assistant to Bülow, but their cooperation did not last long: Weingartner did not like the liberties that Bülow allowed in his interpretation of the classics, and he did not hesitate to tell him about it.

After several years of work in Danzig (Gdansk), Hamburg, Mannheim, Weingartner was already in 1891 appointed the first conductor of the Royal Opera and Symphony Concerts in Berlin, where he established his reputation as one of the leading German conductors.

And since 1908, Vienna has become the center of Weingartner’s activity, where he replaced G. Mahler as head of the opera and the Philharmonic Orchestra. This period also marks the beginning of the world fame of the artist. He tours a lot in all European countries, especially in England, in 1905 he crosses the ocean for the first time, and later, in 1927, performs in the USSR.

Working in Hamburg (1911-1914), Darmstadt (1914-1919), the artist does not break with Vienna and returns here again as director of the Volksoper and conductor of the Vienna Philharmonic (until 1927). Then he settled in Basel, where he conducted an orchestra, studied composition, led a conducting class at the conservatory, surrounded by honor and respect.

It seemed that the aged maestro would never return to active artistic activity. But in 1935, after Clemens Kraus left Vienna, the seventy-two-year-old musician again headed the State Opera and performed at the Salzburg Festival. However, not for long: disagreements with the musicians soon forced him to finally resign. True, even after that, Weingartner still found the strength to undertake a large concert tour of the Far East. And only then he finally settled in Switzerland, where he died.

Weingartner’s fame rested primarily on his interpretation of the symphonies of Beethoven and other classical composers. The monumentality of his concepts, the harmony of forms and the dynamic power of his interpretations made a great impression on the listeners. One of the critics wrote: “Weingartner is a classicist by temperament and school, and he feels best in classical literature. Sensitivity, restraint and a mature intellect give his performance an impressive nobility, and it is often said that the majestic grandiosity of his Beethoven is unattainable by any other conductor of our time. Weingartner is able to affirm the classical line of a piece of music with a hand that always maintains firmness and confidence, he is able to make the most subtle harmonic combinations and the most fragile contrasts audible. But perhaps Weingartner’s most remarkable quality is his extraordinary gift for seeing the work as a whole; he has an instinctive sense of architectonics.”

Music lovers can be convinced of the validity of these words. Despite the fact that the heyday of Weingartner’s artistic activity falls on the years when the recording technique was still very imperfect, his legacy includes a fairly significant number of recordings. Deep readings of all Beethoven’s symphonies, most of the symphonic works of Liszt, Brahms, Haydn, Mendelssohn, as well as the waltzes of I. Strauss, have been preserved for posterity. Weingartner left many literary and musical works containing the most valuable thoughts on the art of conducting and the interpretation of individual compositions.

L. Grigoriev, J. Platek