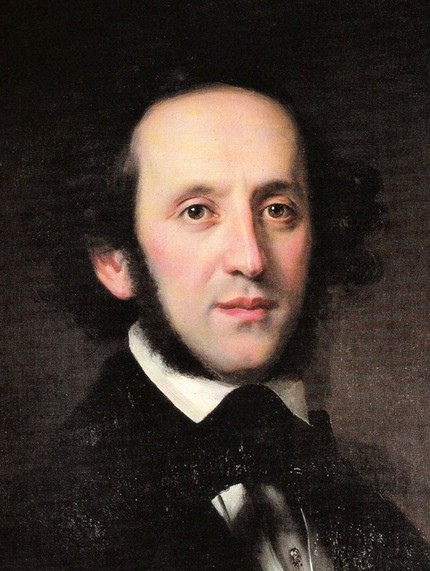

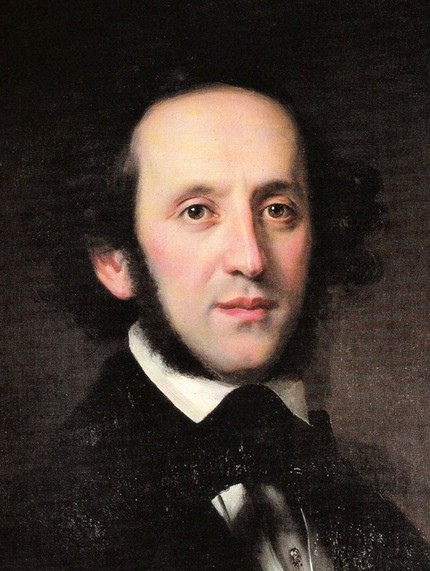

Felix Mendelssohn-Bartholdy (Felix Mendelssohn Bartholdy) |

Felix Mendelssohn Bartholdy

This is Mozart of the nineteenth century, the brightest musical talent, who most clearly comprehends the contradictions of the era and best of all reconciles them. R. Schumann

F. Mendelssohn-Bartholdy is a German composer of the Schumann generation, conductor, teacher, pianist, and musical educator. His varied activity was subordinated to the most noble and serious goals – it contributed to the rise of the musical life of Germany, the strengthening of its national traditions, the education of an enlightened public and educated professionals.

Mendelssohn was born into a family with a long cultural tradition. The grandfather of the future composer is a famous philosopher; father – the head of the banking house, an enlightened man, a fine connoisseur of the arts – gave his son an excellent education. In 1811, the family moved to Berlin, where Mendelssohn took lessons from the most respected teachers – L. Berger (piano), K. Zelter (composition). G. Heine, F. Hegel, T. A. Hoffmann, the Humboldt brothers, K. M. Weber visited the Mendelssohn house. J. W. Goethe listened to the game of the twelve-year-old pianist. Meetings with the great poet in Weimar remained the most beautiful memories of my youth.

Communication with serious artists, various musical impressions, attending lectures at the University of Berlin, the highly enlightened environment in which Mendelssohn grew up – all contributed to his rapid professional and spiritual development. From the age of 9, Mendelssohn has been performing on the concert stage, in the early 20s. his first writings appear. Already in his youth, Mendelssohn’s educational activities began. The performance of J. S. Bach’s Matthew Passion (1829) under his direction became a historic event in the musical life of Germany, served as an impetus for the revival of Bach’s work. In 1833-36. Mendelssohn holds the post of music director in Düsseldorf. The desire to raise the level of performance, to replenish the repertoire with classical works (oratorios by G. F. Handel and I. Haydn, operas by W. A. Mozart, L. Cherubini) ran into the indifference of the city authorities, the inertness of the German burghers.

Mendelssohn’s activity in Leipzig (since 1836) as a conductor of the Gewandhaus orchestra contributed to a new flourishing of the musical life of the city, already in the 100th century. famous for its cultural traditions. Mendelssohn sought to draw the attention of listeners to the greatest works of art of the past (the oratorios of Bach, Handel, Haydn, the Solemn Mass and Beethoven’s Ninth Symphony). Educational goals were also pursued by a cycle of historical concerts – a kind of panorama of the development of music from Bach to contemporary composers Mendelssohn. In Leipzig, Mendelssohn gives concerts of piano music, performs Bach’s organ works in the St. Thomas Church, where the “great cantor” served 1843 years ago. In 38, on the initiative of Mendelssohn, the first conservatory in Germany was opened in Leipzig, on the model of which conservatories were created in other German cities. In the Leipzig years, Mendelssohn’s work reached its highest flowering, maturity, mastery (Violin Concerto, Scottish Symphony, music for Shakespeare’s A Midsummer Night’s Dream, the last notebooks of Songs without Words, oratorio Elijah, etc.). Constant tension, the intensity of performing and teaching activities gradually undermined the strength of the composer. Severe overwork, the loss of loved ones (the sudden death of Fanny’s sister) brought death closer. Mendelssohn died at the age of XNUMX.

Mendelssohn was attracted by various genres and forms, performing means. With equal skill he wrote for the symphony orchestra and piano, choir and organ, chamber ensemble and voice, revealing the true versatility of talent, the highest professionalism. At the very beginning of his career, at the age of 17, Mendelssohn created the overture “A Midsummer Night’s Dream” – a work that struck his contemporaries with the organic conception and embodiment, the maturity of composer’s technique and the freshness and richness of imagination. “The blossoming of youth is felt here, as, perhaps, in no other work of the composer, the finished master made his first takeoff in a happy moment.” In the one-movement program overture, inspired by Shakespeare’s comedy, the boundaries of the composer’s musical and poetic world were defined. This is light fantasy with a touch of scherzo, flight, bizarre play (fantastic dances of elves); lyrical images that combine romantic enthusiasm, excitement and clarity, nobility of expression; folk-genre and pictorial, epic images. The genre of concert program overture created by Mendelssohn was developed in the symphonic music of the 40th century. (G. Berlioz, F. Liszt, M. Glinka, P. Tchaikovsky). In the early XNUMXs. Mendelssohn returned to Shakespearean comedy and wrote music for the play. The best numbers made up an orchestral suite, firmly established in the concert repertoire (Overture, Scherzo, Intermezzo, Nocturne, Wedding March).

The content of many of Mendelssohn’s works is connected with direct life impressions from travels to Italy (sunny, permeated with southern light and warmth “Italian Symphony” – 1833), as well as to the northern countries – England and Scotland (images of the sea element, the northern epic in the overtures “Fingal’s Cave ”(“The Hebrides”), “Sea Silence and Happy Sailing” (both 1832), in the “Scottish” Symphony (1830-42).

The basis of Mendelssohn’s piano work was “Songs without Words” (48 pieces, 1830-45) – wonderful examples of lyrical miniatures, a new genre of romantic piano music. In contrast to the spectacular bravura pianism that was widespread at that time, Mendelssohn created pieces in a chamber style, revealing above all the cantilena, melodious possibilities of the instrument. The composer was also attracted by the elements of concert playing – virtuoso brilliance, festivity, elation corresponded to his artistic nature (2 concertos for piano and orchestra, Brilliant Capriccio, Brilliant Rondo, etc.). The famous Violin Concerto in E minor (1844) entered the classical fund of the genre along with concertos by P. Tchaikovsky, I. Brahms, A. Glazunov, J. Sibelius. The oratorios “Paul”, “Elijah”, the cantata “The First Walpurgis Night” (according to Goethe) made a significant contribution to the history of cantata-oratorio genres. The development of the original traditions of German music was continued by Mendelssohn’s preludes and fugues for organ.

The composer intended many choral works for amateur choral societies in Berlin, Düsseldorf and Leipzig; and chamber compositions (songs, vocal and instrumental ensembles) – for amateur, home music-making, extremely popular in Germany at all times. The creation of such music, addressed to enlightened amateurs, and not only to professionals, contributed to the implementation of Mendelssohn’s main creative goal – educating the tastes of the public, actively introducing it to a serious, highly artistic heritage.

I. Okhalova

- Creative path →

- Symphonic creativity →

- Overtures →

- Oratorios →

- Piano creativity →

- «Songs without words» →

- String quartets →

- List of works →

The place and position of Mendelssohn in the history of German music was correctly identified by P. I. Tchaikovsky. Mendelssohn, in his words, “will always remain a model of impeccable purity of style, and behind him will be recognized a sharply defined musical individuality, pale before the radiance of such geniuses as Beethoven – but highly advanced from the crowd of numerous artisan musicians of the German school.”

Mendelssohn is one of the artists whose conception and implementation have reached a degree of unity and integrity that some of his contemporaries of a brighter and larger-scale talent did not always manage to achieve.

The creative path of Mendelssohn does not know sudden breakdowns and daring innovations, crisis states and steep ascents. This does not mean that it proceeded thoughtlessly and cloudlessly. His first individual “application” for a master and independent creator – the overture “A Midsummer Night’s Dream” – is a pearl of symphonic music, the fruit of a great and purposeful work, prepared by years of professional training.

The seriousness of the special knowledge acquired from childhood, the versatile intellectual development helped Mendelssohn at the dawn of his creative life to accurately outline the circle of images that fascinated him, which for a long time, if not forever, captured his imagination. In the world of a captivating fairy tale, he seemed to have found himself. Drawing a magical game of illusory images, Mendelssohn metaphorically expressed his poetic vision of the real world. Life experience, knowledge of centuries of accumulated cultural values sated the intellect, introduced “corrections” into the process of artistic improvement, significantly deepening the content of music, supplementing it with new motives and shades.

However, the harmonic integrity of Mendelssohn’s musical talent was combined with the narrowness of his creative range. Mendelssohn is far from the passionate impulsiveness of Schumann, the excited exaltation of Berlioz, the tragedy and national-patriotic heroics of Chopin. Strong emotions, the spirit of protest, the persistent search for new forms, he opposed the calmness of thought and the warmth of human feeling, the strict orderliness of forms.

At the same time, Mendelssohn’s figurative thinking, the content of his music, as well as the genres in which he creates, do not go beyond the mainstream of the art of romanticism.

A Midsummer Night’s Dream or the Hebrides are no less romantic than the works of Schumann or Chopin, Schubert or Berlioz. This is typical of the many-sided musical romanticism, in which various currents intersected, at first glance seeming polar.

Mendelssohn adjoins the wing of German romanticism, which originates from Weber. The fabulousness and fantasy characteristic of Weber, the animated world of nature, the poetry of distant legends and tales, updated and expanded, shimmers in Mendelssohn’s music with newly found colorful tones.

Of the vast range of romantic themes touched upon by Mendelssohn, the themes related to the realm of fantasy received the most artistically completed embodiment. There is nothing gloomy or demonic in Mendelssohn’s fantasy. These are bright images of nature, born of folk fantasy and scattered in many fairy tales, myths, or inspired by epic and historical legends, where reality and fantasy, reality and poetic fiction are closely intertwined.

From the folk origins of figurativeness – the unobscured coloring, with which the lightness and grace, soft lyrics and flight of Mendelssohn’s “fantastic” music so naturally harmonize.

The romantic theme of nature is no less close and natural for this artist. Relatively rarely resorting to external descriptiveness, Mendelssohn conveys a certain “mood” of the landscape with the finest expressive techniques, evoking its lively emotional sensation.

Mendelssohn, an outstanding master of the lyrical landscape, left magnificent pages of pictorial music in such works as The Hebrides, A Midsummer Night’s Dream, The Scottish Symphony. But the images of nature, fantasy (often they are inextricably woven) are imbued with soft lyricism. Lyricism – the most essential property of Mendelssohn’s talent – colors all his work.

Despite his commitment to the art of the past, Mendelssohn is the son of his age. The lyrical aspect of the world, the lyrical element predetermined the direction of his artistic searches. Coinciding with this general trend in Romantic music is Mendelssohn’s constant fascination with instrumental miniatures. In contrast to the art of classicism and Beethoven, who cultivated complex monumental forms, commensurate with the philosophical generalization of life processes, in the art of the Romantics, the forefront is given to the song, a small instrumental miniature. To capture the most subtle and transient shades of feeling, small forms turned out to be the most organic.

A strong connection with democratic everyday art ensured the “strength” of a new type of musical creativity, helped to develop a certain tradition for it. Since the beginning of the XNUMXth century, lyrical instrumental miniature has taken the position of one of the leading genres. Widely represented in the work of Weber, Field, and especially Schubert, the genre of instrumental miniature has stood the test of time, continuing to exist and develop in the new conditions of the XNUMXth century. Mendelssohn is the direct successor of Schubert. Charming miniatures adjoin Schubert’s impromptu – the pianoforte Songs Without Words. These pieces captivate with their genuine sincerity, simplicity and sincerity, completeness of forms, exceptional grace and skill.

An exact description of Mendelssohn’s work is given by Anton Grigorievich Rubinshtein: “… in comparison with other great writers, he (Mendelssohn. – V. G.) lacked depth, seriousness, grandeur…”, but “…all his creations are a model in terms of perfection of form, technique and harmony… His “Songs without Words” is a treasure in terms of lyrics and piano charm… His “Violin Concerto” is unique in freshness, beauty and noble virtuosity … These works (among which Rubinstein includes A Midsummer Night’s Dream and Fingal’s Cave. – V. G.) … put him on a par with the highest representatives of musical art … “

Mendelssohn wrote a huge number of works in various genres. Among them are many works of large forms: oratorios, symphonies, concert overtures, sonatas, concertos (piano and violin), a lot of instrumental chamber-ensemble music: trios, quartets, quintets, octets. There are spiritual and secular vocal and instrumental compositions, as well as music for dramatic plays. Significant tribute was paid by Mendelssohn to the popular genre of vocal ensemble; he wrote many solo pieces for individual instruments (mainly for the piano) and for voice.

Valuable and interesting is contained in each area of Mendelssohn’s work, in any of the listed genres. All the same, the most typical, strong features of the composer manifested themselves in two seemingly non-contiguous areas – in the lyrics of piano miniatures and in the fantasy of his orchestral works.

V. Galatskaya

The work of Mendelssohn is one of the most significant phenomena in the German culture of the 19th century. Along with the work of such artists as Heine, Schumann, the young Wagner, it reflected the artistic upsurge and social changes that took place between the two revolutions (1830 and 1848).

The cultural life of Germany, with which all the activities of Mendelssohn are inextricably linked, in the 30s and 40s was characterized by a significant revival of democratic forces. The opposition of radical circles, irreconcilably opposed to the reactionary absolutist government, assumed more and more open political forms and penetrated into various spheres of the spiritual life of the people. Socially accusatory tendencies in literature (Heine, Berne, Lenau, Gutskov, Immermann) were clearly manifested, a school of “political poetry” was formed (Weert, Herweg, Freiligrat), scientific thought flourished, aimed at studying national culture (studies on the history of the German language, mythology and literature belonging to Grimm, Gervinus, Hagen).

The organization of the first German musical festivals, the staging of national operas by Weber, Spohr, Marschner, the young Wagner, the dissemination of educational musical journalism in which the struggle for progressive art was waged (Schumann’s newspaper in Leipzig, A. Marx’s in Berlin) – all this, along with many other similar facts, spoke of the growth of national self-consciousness. Mendelssohn lived and worked in that atmosphere of protest and intellectual ferment, which left a characteristic imprint on the culture of Germany in the 30s and 40s.

In the struggle against the narrowness of the burgher circle of interests, against the decline of the ideological role of art, the progressive artists of that time chose different paths. Mendelssohn saw his appointment in the revival of the high ideals of classical music.

Indifferent to the political forms of struggle, deliberately neglecting, unlike many of his contemporaries, the weapon of musical journalism, Mendelssohn was nevertheless an outstanding artist-educator.

All his many-sided activity as a composer, conductor, pianist, organizer, teacher was imbued with educational ideas. In the democratic art of Beethoven, Handel, Bach, Gluck, he saw the highest expression of spiritual culture and fought with inexhaustible energy to establish their principles in the modern musical life of Germany.

Mendelssohn’s progressive aspirations determined the nature of his own work. Against the backdrop of fashionable light-weight music of bourgeois salons, popular stage and entertainment theater, Mendelssohn’s works attracted with their seriousness, chastity, “impeccable purity of style” (Tchaikovsky).

A remarkable feature of Mendelssohn’s music was its wide availability. In this respect, the composer occupied an exceptional position among his contemporaries. Mendelssohn’s art corresponded to the artistic tastes of a broad democratic environment (especially German). His themes, images and genres were closely connected with contemporary German culture. The works of Mendelssohn widely reflected the images of national poetic folklore, the latest Russian poetry and literature. He firmly relied on the musical genres that have long existed in the German democratic environment.

The great choral works of Mendelssohn are organically connected with the ancient national traditions that go back not only to Beethoven, Mozart, Haydn, but even further, into the depths of history – to Bach, Handel (and even Schutz). The modern, widely popular “leaderthafel” movement was reflected not only in the numerous choirs of Mendelssohn, but also in many instrumental compositions, in particular, on the famous “Songs without Glories”. He was invariably attracted by everyday forms of German urban music – romance, chamber ensemble, various types of home piano music. The characteristic style of modern everyday genres even penetrated into the works of the composer, written in a monumental-classicist manner.

Finally, Mendelssohn showed great interest in folk song. In many works, especially in romances, he sought to approach the intonations of German folklore.

Mendelssohn’s adherence to the classicist traditions brought him reproaches of conservatism from the side of the radical young composers. Meanwhile, Mendelssohn was infinitely far from those numerous epigones who, under the guise of fidelity to the classics, littered the music with mediocre rehashings of the works of a bygone era.

Mendelssohn did not imitate the classics, he tried to revive their viable and advanced principles. A lyricist par excellence, Mendelssohn created typically romantic images in his works. Here are “musical moments”, reflecting the state of the artist’s inner world, and subtle, spiritualized pictures of nature and life. At the same time, in Mendelssohn’s music there are no traces of mysticism, nebula, so characteristic of the reactionary trends of German romanticism. In the art of Mendelssohn everything is clear, sober, vital.

“Everywhere you step on solid ground, on flourishing German soil,” Schumann said of Mendelssohn’s music. There is also something Mozartian in her graceful, transparent appearance.

The musical style of Mendelssohn is certainly individual. The clear melody associated with everyday song style, genre and dance elements, the tendency to motivate development, and finally, balanced, polished forms bring Mendelssohn’s music closer to the art of the German classics. But the classicist way of thinking is combined in his work with romantic features. His harmonic language and instrumentation are characterized by an increased interest in colorfulness. Mendelssohn is especially close to the chamber genres typical of German romantics. He thinks in terms of the sounds of a new piano, a new orchestra.

With all the seriousness, nobility, and democratic nature of his music, Mendelssohn still did not achieve the creative depth and power characteristic of his great predecessors. The petty-bourgeois environment, against which he fought, left a noticeable imprint on his own work. For the most part, it is devoid of passion, genuine heroism, it lacks philosophical and psychological depths, and there is a noticeable lack of dramatic conflict. The image of the modern hero, with his more complicated mental and emotional life, was not reflected in the works of the composer. Mendelssohn most of all tends to display the bright sides of life. His music is predominantly elegiac, sensitive, with a lot of youthful carefree playfulness.

But against the backdrop of a tense, contradictory era that enriched art with the rebellious romance of Byron, Berlioz, Schumann, the calm nature of Mendelssohn’s music speaks of a certain limitation. The composer reflected not only the strength, but also the weakness of his socio-historical environment. This duality predetermined the peculiar fate of his creative heritage.

During his lifetime and for some time after his death, public opinion was inclined to evaluate the composer as the most important musician of the post-Beethoven era. In the second half of the century, a disdainful attitude towards the legacy of Mendelssohn appeared. This was greatly facilitated by his epigones, in whose works the classical features of Mendelssohn’s music degenerated into academicism, and its lyrical content, gravitating toward sensitivity, into frank sentimentality.

And yet, between Mendelssohn and “Mendelssohnism” one cannot put an equal sign, although one cannot deny the well-known emotional limitations of his art. The seriousness of the idea, the classical perfection of form with the freshness and novelty of artistic means – all this makes Mendelssohn’s work related to works that have firmly and deeply entered the life of the German people, into their national culture.

V. Konen

- Creative path of Mendelssohn →