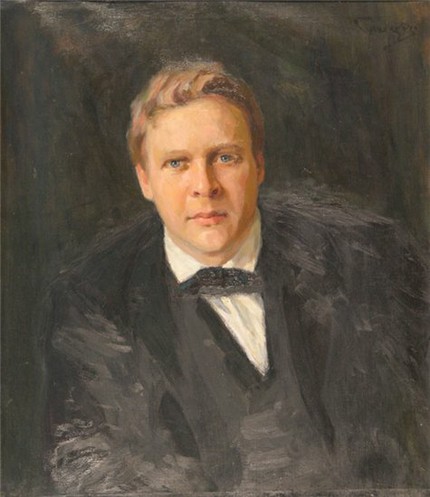

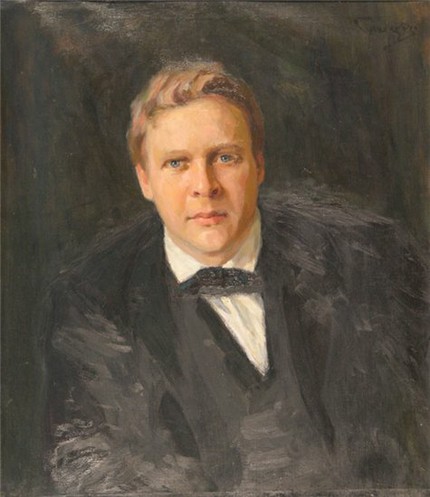

Fedor Ivanovich Chaliapin (Feodor Chaliapin) |

Feodor Chaliapin

Fedor Ivanovich Chaliapin was born on February 13, 1873 in Kazan, in a poor family of Ivan Yakovlevich Chaliapin, a peasant from the village of Syrtsovo, Vyatka province. Mother, Evdokia (Avdotya) Mikhailovna (nee Prozorova), originally from the village of Dudinskaya in the same province. Already in childhood, Fedor had a beautiful voice (treble) and often sang along with his mother, “adjusting his voice.” From the age of nine he sang in church choirs, tried to learn to play the violin, read a lot, but was forced to work as an apprentice shoemaker, turner, carpenter, bookbinder, copyist. At the age of twelve, he participated in the performances of a troupe touring in Kazan as an extra. An irrepressible craving for the theater led him to various acting troupes, with which he wandered around the cities of the Volga region, the Caucasus, Central Asia, working either as a loader or a hooker on the pier, often starving and spending the night on benches.

In Ufa 18 December 1890, he sang the solo part for the first time. From the memoirs of Chaliapin himself:

“… Apparently, even in the modest role of a chorister, I managed to show my natural musicality and good voice means. When one day one of the baritones of the troupe suddenly, on the eve of the performance, for some reason refused the role of Stolnik in Moniuszko’s opera “Galka”, and there was no one in the troupe to replace him, the entrepreneur Semyonov-Samarsky asked me if I would agree to sing this part. Despite my extreme shyness, I agreed. It was too tempting: the first serious role in my life. I quickly learned the part and performed.

Despite the sad incident in this performance (I sat down on the stage past a chair), Semyonov-Samarsky was nevertheless moved by both my singing and my conscientious desire to portray something similar to a Polish magnate. He added five rubles to my salary and also began to entrust me with other roles. I still think superstitiously: a good sign for a beginner in the first performance on stage in front of an audience is to sit past the chair. Throughout my subsequent career, however, I vigilantly watched the chair and was afraid not only to sit by, but also to sit in the chair of another …

In this first season of mine, I also sang Fernando in Il trovatore and Neizvestny in Askold’s Grave. Success finally strengthened my decision to devote myself to the theater.

Then the young singer moved to Tiflis, where he took free singing lessons from the famous singer D. Usatov, performed in amateur and student concerts. In 1894 he sang in performances that took place in the St. Petersburg suburban garden “Arcadia”, then in the Panaevsky Theater. On April 1895, XNUMX, he made his debut as Mephistopheles in Gounod’s Faust at the Mariinsky Theatre.

In 1896, Chaliapin was invited by S. Mamontov to the Moscow Private Opera, where he took a leading position and fully revealed his talent, creating over the years of work in this theater a whole gallery of unforgettable images in Russian operas: Ivan the Terrible in N. Rimsky’s The Maid of Pskov -Korsakov (1896); Dositheus in M. Mussorgsky’s “Khovanshchina” (1897); Boris Godunov in the opera of the same name by M. Mussorgsky (1898) and others.

Communication in the Mammoth Theater with the best artists of Russia (V. Polenov, V. and A. Vasnetsov, I. Levitan, V. Serov, M. Vrubel, K. Korovin and others) gave the singer powerful incentives for creativity: their scenery and costumes helped in creating a compelling stage presence. The singer prepared a number of opera parts in the theater with the then novice conductor and composer Sergei Rachmaninoff. Creative friendship united two great artists until the end of their lives. Rachmaninov dedicated several romances to the singer, including “Fate” (verses by A. Apukhtin), “You knew him” (verses by F. Tyutchev).

The deeply national art of the singer delighted his contemporaries. “In Russian art, Chaliapin is an era, like Pushkin,” wrote M. Gorky. Based on the best traditions of the national vocal school, Chaliapin opened a new era in the national musical theater. He was able to surprisingly organically combine the two most important principles of opera art – dramatic and musical – to subordinate his tragic gift, unique stage plasticity and deep musicality to a single artistic concept.

From September 24, 1899, Chaliapin, the leading soloist of the Bolshoi and at the same time the Mariinsky Theater, toured abroad with triumphant success. In 1901, in Milan’s La Scala, he sang with great success the part of Mephistopheles in the opera of the same name by A. Boito with E. Caruso, conducted by A. Toscanini. The world fame of the Russian singer was confirmed by tours in Rome (1904), Monte Carlo (1905), Orange (France, 1905), Berlin (1907), New York (1908), Paris (1908), London (1913/14). The divine beauty of Chaliapin’s voice captivated listeners of all countries. His high bass, delivered by nature, with a velvety, soft timbre, sounded full-blooded, powerful and had a rich palette of vocal intonations. The effect of artistic transformation amazed the listeners – there is not only an external appearance, but also a deep inner content, which was conveyed by the vocal speech of the singer. In creating capacious and scenically expressive images, the singer is helped by his extraordinary versatility: he is both a sculptor and an artist, writes poetry and prose. Such a versatile talent of the great artist is reminiscent of the masters of the Renaissance – it is no coincidence that contemporaries compared his opera heroes with the titans of Michelangelo. The art of Chaliapin crossed national borders and influenced the development of the world opera house. Many Western conductors, artists and singers could repeat the words of the Italian conductor and composer D. Gavazeni: “Chaliapin’s innovation in the sphere of the dramatic truth of opera art had a strong impact on the Italian theater … The dramatic art of the great Russian artist left a deep and lasting mark not only in the field of performance Russian operas by Italian singers, but in general, on the whole style of their vocal and stage interpretation, including works by Verdi … “

“Chaliapin was attracted by the characters of strong people, embraced by an idea and passion, experiencing a deep spiritual drama, as well as vivid comedic images,” notes D.N. Lebedev. – With stunning truthfulness and strength, Chaliapin reveals the tragedy of the unfortunate father distraught with grief in “Mermaid” or the painful mental discord and remorse experienced by Boris Godunov.

In sympathy for human suffering, high humanism is manifested – an inalienable property of progressive Russian art, based on nationality, on purity and depth of feelings. In this nationality, which filled the whole being and all the work of Chaliapin, the strength of his talent is rooted, the secret of his persuasiveness, comprehensibility to everyone, even to an inexperienced person.

Chaliapin is categorically against simulated, artificial emotionality: “All music always expresses feelings in one way or another, and where there are feelings, mechanical transmission leaves the impression of terrible monotony. A spectacular aria sounds cold and formal if the intonation of the phrase is not developed in it, if the sound is not colored with the necessary shades of emotions. Western music also needs this intonation… which I recognized as obligatory for the transmission of Russian music, although it has less psychological vibration than Russian music.”

Chaliapin is characterized by a bright, rich concert activity. Listeners were invariably delighted with his performance of the romances The Miller, The Old Corporal, Dargomyzhsky’s Titular Counsellor, The Seminarist, Mussorgsky’s Trepak, Glinka’s Doubt, Rimsky-Korsakov’s The Prophet, Tchaikovsky’s The Nightingale, The Double Schubert, “I am not angry”, “In a dream I wept bitterly” by Schumann.

Here is what the remarkable Russian musicologist academician B. Asafiev wrote about this side of the singer’s creative activity:

“Chaliapin sang truly chamber music, sometimes so concentrated, so deep that it seemed that he had nothing in common with the theater and never resorted to the emphasis on accessories and the appearance of expression required by the stage. Perfect calmness and restraint took possession of him. For example, I remember Schumann’s “In my dream I wept bitterly” – one sound, a voice in silence, a modest, hidden emotion, but there seems to be no performer, and this large, cheerful, generous with humor, affection, clear person. A lonely voice sounds – and everything is in the voice: all the depth and fullness of the human heart … The face is motionless, the eyes are extremely expressive, but in a special way, not like, say, Mephistopheles in the famous scene with students or in a sarcastic serenade: there they burned maliciously, mockingly, and then the eyes of a man who felt the elements of sorrow, but who understood that only in the harsh discipline of the mind and heart – in the rhythm of all its manifestations – does a person gain power over both passions and suffering.

The press loved to calculate the artist’s fees, supporting the myth of fabulous wealth, Chaliapin’s greed. What if this myth is refuted by posters and programs of many charity concerts, famous performances of the singer in Kyiv, Kharkov and Petrograd in front of a huge working audience? Idle rumors, newspaper rumors and gossip more than once forced the artist to take up his pen, refute sensations and speculation, and clarify the facts of his own biography. Useless!

During the First World War, Chaliapin’s tours ceased. The singer opened two infirmaries for wounded soldiers at his own expense, but did not advertise his “good deeds”. Lawyer M.F. Volkenstein, who managed the singer’s financial affairs for many years, recalled: “If only they knew how much Chaliapin’s money went through my hands to help those who needed it!”

After the October Revolution of 1917, Fyodor Ivanovich was engaged in the creative reconstruction of the former imperial theaters, was an elected member of the directorates of the Bolshoi and Mariinsky theaters, and in 1918 directed the artistic part of the latter. In the same year, he was the first of the artists to be awarded the title of People’s Artist of the Republic. The singer sought to get away from politics, in the book of his memoirs he wrote: “If in my life I was anything but an actor and a singer, I was completely devoted to my vocation. But least of all I was a politician.”

Outwardly, it might seem that Chaliapin’s life is prosperous and creatively rich. He is invited to perform at official concerts, he also performs a lot for the general public, he is awarded honorary titles, asked to head the work of various kinds of artistic juries, theater councils. But then there are sharp calls to “socialize Chaliapin”, “put his talent at the service of the people”, doubts are often expressed about the “class loyalty” of the singer. Someone demands the obligatory involvement of his family in the performance of labor service, someone makes direct threats to the former artist of the imperial theaters … “I saw more and more clearly that no one needs what I can do, that there is no point in my work” , – the artist admitted.

Of course, Chaliapin could protect himself from the arbitrariness of zealous functionaries by making a personal request to Lunacharsky, Peters, Dzerzhinsky, Zinoviev. But to be in constant dependence on the orders of even such high-ranking officials of the administrative-party hierarchy is humiliating for an artist. In addition, they often did not guarantee full social security and certainly did not inspire confidence in the future.

In the spring of 1922, Chaliapin did not return from foreign tours, although for some time he continued to consider his non-return to be temporary. The home environment played a significant role in what happened. Caring for children, the fear of leaving them without a livelihood forced Fedor Ivanovich to agree to endless tours. The eldest daughter Irina remained to live in Moscow with her husband and mother, Paula Ignatievna Tornagi-Chaliapina. Other children from the first marriage – Lydia, Boris, Fedor, Tatyana – and children from the second marriage – Marina, Martha, Dassia and the children of Maria Valentinovna (second wife), Edward and Stella, lived with them in Paris. Chaliapin was especially proud of his son Boris, who, according to N. Benois, achieved “great success as a landscape and portrait painter.” Fyodor Ivanovich willingly posed for his son; portraits and sketches of his father made by Boris “are priceless monuments to the great artist …”.

In a foreign land, the singer enjoyed constant success, touring in almost all countries of the world – in England, America, Canada, China, Japan, and the Hawaiian Islands. From 1930, Chaliapin performed in the Russian Opera company, whose performances were famous for their high level of staging culture. The operas Mermaid, Boris Godunov, and Prince Igor were especially successful in Paris. In 1935, Chaliapin was elected a member of the Royal Academy of Music (together with A. Toscanini) and was awarded an academic diploma. Chaliapin’s repertoire included about 70 parts. In operas by Russian composers, he created images of Melnik (Mermaid), Ivan Susanin (Ivan Susanin), Boris Godunov and Varlaam (Boris Godunov), Ivan the Terrible (The Maid of Pskov) and many others, unsurpassed in strength and truth of life. . Among the best roles in Western European opera are Mephistopheles (Faust and Mephistopheles), Don Basilio (The Barber of Seville), Leporello (Don Giovanni), Don Quixote (Don Quixote). Just as great was Chaliapin in chamber vocal performance. Here he introduced an element of theatricality and created a kind of “romance theater”. His repertoire included up to four hundred songs, romances and other genres of chamber and vocal music. Among the masterpieces of performing arts are “Bloch”, “Forgotten”, “Trepak” by Mussorgsky, “Night Review” by Glinka, “Prophet” by Rimsky-Korsakov, “Two Grenadiers” by R. Schumann, “Double” by F. Schubert, as well as Russian folk songs “Farewell, joy”, “They don’t tell Masha to go beyond the river”, “Because of the island to the core”.

In the 20s and 30s he made about three hundred recordings. “I love gramophone records…” Fedor Ivanovich confessed. “I am excited and creatively excited by the idea that the microphone symbolizes not any particular audience, but millions of listeners.” The singer was very picky about recordings, among his favorites is the recording of Massenet’s “Elegy”, Russian folk songs, which he included in the programs of his concerts throughout his creative life. According to Asafiev’s recollection, “the great, powerful, inescapable breath of the great singer sated the melody, and, it was heard, there was no limit to the fields and steppes of our Motherland.”

On August 24, 1927, the Council of People’s Commissars adopts a resolution depriving Chaliapin of the title of People’s Artist. Gorky did not believe in the possibility of removing the title of People’s Artist from Chaliapin, which was already rumored in the spring of 1927: will do.” However, in reality, everything happened differently, not at all the way Gorky imagined …

Commenting on the decision of the Council of People’s Commissars, A.V. Lunacharsky resolutely dismissed the political background, argued that “the only motive for depriving Chaliapin of the title was his stubborn unwillingness to come at least for a short time to his homeland and artistically serve the very people whose artist he was proclaimed …”

However, in the USSR they did not abandon attempts to return Chaliapin. In the autumn of 1928, Gorky wrote to Fyodor Ivanovich from Sorrento: “They say you will sing in Rome? I’ll come to listen. They really want to listen to you in Moscow. Stalin, Voroshilov and others told me this. Even the “rock” in the Crimea and some other treasures would be returned to you.”

The meeting in Rome took place in April 1929. Chaliapin sang “Boris Godunov” with great success. After the performance, we gathered at the Library tavern. “Everyone was in a very good mood. Alexei Maksimovich and Maxim told a lot of interesting things about the Soviet Union, answered a lot of questions, in conclusion, Alexei Maksimovich told Fedor Ivanovich: “Go home, look at the construction of a new life, at new people, their interest in you is huge, seeing you will want to stay there, I’m sure.” The daughter-in-law of the writer N.A. Peshkova continues: “Maria Valentinovna, who was listening in silence, suddenly declared decisively, turning to Fyodor Ivanovich:“ You will go to the Soviet Union only over my corpse. Everyone’s mood dropped, they quickly got ready to go home. Chaliapin and Gorky did not meet again.

Far from home, for Chaliapin, meetings with Russians were especially dear – Korovin, Rachmaninov, Anna Pavlova. Chaliapin was acquainted with Toti Dal Monte, Maurice Ravel, Charlie Chaplin, Herbert Wells. In 1932, Fedor Ivanovich starred in the film Don Quixote at the suggestion of the German director Georg Pabst. The film was popular with the public. Already in his declining years, Chaliapin yearned for Russia, gradually lost his cheerfulness and optimism, did not sing new opera parts, and began to get sick often. In May 1937, doctors diagnosed him with leukemia. On April 12, 1938, the great singer died in Paris.

Until the end of his life, Chaliapin remained a Russian citizen – he did not accept foreign citizenship, he dreamed of being buried in his homeland. His wish came true, the ashes of the singer were transported to Moscow and on October 29, 1984 they were buried at the Novodevichy cemetery.