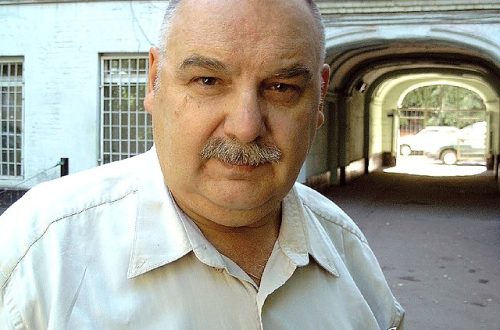

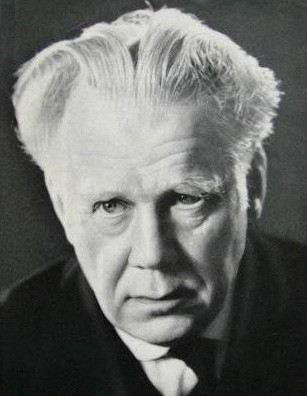

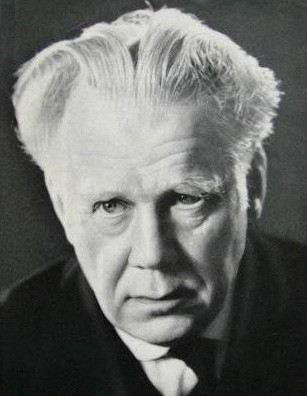

Edwin Fischer |

Edwin Fischer

The second half of our century is considered to be the era of technical perfection of piano playing, performing arts in general. Indeed, now on the stage it is almost impossible to meet an artist who would not be capable of pianistic “acrobatics” of a high rank. Some people, hastily associating this with the general technical progress of mankind, were already inclined to declare the smoothness and fluency of the game as qualities necessary and sufficient for reaching artistic heights. But time judged otherwise, recalling that pianism is not figure skating or gymnastics. Years passed, and it became clear that as the performance technique improved in general, its share in the overall assessment of the performance of this or that artist was steadily declining. Is this why the number of truly great pianists has not increased at all due to such general growth?! In an era when “everyone has learned to play the piano,” truly artistic values - content, spirituality, expressiveness – remained unshakable. And this prompted millions of listeners to turn again to the legacy of those great musicians who have always placed these great values at the forefront of their art.

One such artist was Edwin Fisher. The pianistic history of the XNUMXth century is unthinkable without his contribution, although some of the modern researchers have tried to question the art of the Swiss artist. What else but a purely American passion for “perfectionism” can explain that G. Schonberg in his book, published only three years after the death of the artist, did not consider it necessary to give Fischer more than … one line. However, even during his lifetime, along with signs of love and respect, he had to endure reproaches for imperfection from pedantic critics, who now and then registered his mistakes and seemed to rejoice at him. Didn’t the same thing happen to his older contemporary A. Corto?!

The biographies of the two artists are generally very similar in their main features, despite the fact that in terms of purely pianistic, in terms of the “school”, they are completely different; and this similarity makes it possible to understand the origins of the art of both, the origins of their aesthetics, which is based on the idea of the interpreter primarily as an artist.

Edwin Fischer was born in Basel, in a family of hereditary musical masters, originating from the Czech Republic. Since 1896, he studied at the music gymnasium, then at the conservatory under the direction of X. Huber, and improved at the Berlin Stern Conservatory under M. Krause (1904-1905). In 1905, he himself began to lead a piano class at the same conservatory, at the same time starting his artistic career – first as an accompanist for the singer L. Vulner, and then as a soloist. He was quickly recognized and loved by listeners in many European countries. Especially wide popularity was brought to him by joint performances with A. Nikish, f. Wenngartner, W. Mengelberg, then W. Furtwängler and other major conductors. In communication with these major musicians, his creative principles were developed.

By the 30s, the scope of Fischer’s concert activity was so wide that he left teaching and devoted himself entirely to playing the piano. But over time, the versatile gifted musician became cramped within the framework of his favorite instrument. He created his own chamber orchestra, performed with him as a conductor and soloist. True, this was not dictated by the musician’s ambitions as a conductor: it was just that his personality was so powerful and original that he preferred, not always having such partners at hand as the named masters, to play without a conductor. At the same time, he did not limit himself to the classics of the 1933th-1942th centuries (which has now become almost commonplace), but he directed the orchestra (and managed it perfectly!) even when performing monumental Beethoven concertos. In addition, Fischer was a member of a wonderful trio with violinist G. Kulenkampf and cellist E. Mainardi. Finally, over time, he returned to pedagogy: in 1948 he became a professor at the Higher School of Music in Berlin, but in 1945 he managed to leave Nazi Germany for his homeland, settling in Lucerne, where he spent the last years of his life. Gradually, the intensity of his concert performances decreased: a hand illness often prevented him from performing. However, he continued to play, conduct, record, participate in the trio, where G. Kulenkampf was replaced by V. Schneiderhan in 1958. In 1945-1956, Fischer taught piano lessons in Hertenstein (near Lucerne), where dozens of young artists from all over the world flocked to him every year. Many of them became major musicians. Fischer wrote music, composed cadenzas for classical concertos (by Mozart and Beethoven), edited classical compositions, and finally became the author of several major studies – “J.-S. Bach” (1956), “L. van Beethoven. Piano Sonatas (1960), as well as numerous articles and essays collected in the books Musical Reflections (1956) and On the Tasks of Musicians (XNUMX). In XNUMX, the university of the pianist’s hometown, Basel, elected him an honorary doctorate.

Such is the outer outline of the biography. Parallel to it was the line of the internal evolution of his artistic appearance. At first, in the first decades, Fischer gravitated towards an emphatically expressive manner of playing, his interpretations were marked by some extremes and even liberties of subjectivism. At that time, the music of the Romantics was at the center of his creative interests. True, despite all the deviations from tradition, he captivated the audience with the transfer of the courageous energy of Schumann, the majesty of Brahms, the heroic rise of Beethoven, the drama of Schubert. Over the years, the artist’s performing style became more restrained, clarified, and the center of gravity shifted to the classics – Bach and Mozart, although Fischer did not part with the romantic repertoire. During this period, he is especially clearly aware of the performer’s mission as an intermediary, “a medium between the eternal, divine art and the listener.” But the mediator is not indifferent, standing aside, but active, refracting this “eternal, divine” through the prism of his “I”. The motto of the artist remains the words expressed by him in one of the articles: “Life must pulsate in performance; crescendos and fortes that are not experienced look artificial.”

The features of the artist’s romantic nature and his artistic principles came to complete harmony in the last period of his life. V. Furtwangler, having visited his concert in 1947, noted that “he really reached his heights.” His game struck with the strength of experience, the trembling of each phrase; it seemed that the work was born anew every time under the fingers of the artist, who was completely alien to the stamp and routine. During this period, he again turned to his favorite hero, Beethoven, and made recordings of Beethoven concertos in the mid-50s (in most cases he himself led the London Philharmonic Orchestra), as well as a number of sonatas. These recordings, along with those made earlier, back in the 30s, became the basis of Fischer’s sounding legacy – a legacy that, after the artist’s death, caused a lot of controversy.

Of course, the records do not fully convey to us the charm of Fischer’s playing, they only partially convey the captivating emotionality of his art, the grandeur of concepts. For those who heard the artist in the hall, they are, indeed, nothing more than a reflection of former impressions. The reasons for this are not difficult to discover: in addition to the specific features of his pianism, they also lie in a prosaic plane: the pianist was simply afraid of the microphone, he felt awkward in the studio, without an audience, and overcoming this fear was rarely given to him without loss. In the recordings, one can feel traces of nervousness, and some lethargy, and technical “marriage”. All this more than once served as a target for the zealots of “purity”. And the critic K. Franke was right: “The herald of Bach and Beethoven, Edwin Fischer left behind not only false notes. Moreover, it can be said that even Fischer’s false notes are characterized by the nobility of high culture, deep feeling. Fischer was precisely an emotional nature – and this is his greatness and his limitations. The spontaneity of his playing finds its continuation in his articles… He behaved at the desk the same way as at the piano – he remained a man of naive faith, and not reason and knowledge.”

For an unprejudiced listener, it immediately becomes obvious that even in the early recordings of Beethoven’s sonatas, made back in the late 30s, the scale of the artist’s personality, the significance of his playing music, are fully felt. Enormous authority, romantic pathos, combined with an unexpected but convincing restraint of feeling, deep thoughtfulness and justification of dynamic lines, the power of culminations – all this makes an irresistible impression. One involuntarily recalls Fischer’s own words, who argued in his book “Musical Reflections” that an artist playing Beethoven should combine pianist, singer and violinist “in one person”. It is this feeling that allows him to so completely immerse himself in the music with his interpretation of the Appassionata that the high simplicity involuntarily makes you forget about the shadowy sides of the performance.

High harmony, classical clarity are, perhaps, the main attractive force of his later recordings. Here already his penetration into the depths of Beethoven’s spirit is determined by experience, life wisdom, comprehension of the classical heritage of Bach and Mozart. But, despite the age, the freshness of perception and experience of music is clearly felt here, which cannot but be transmitted to the listeners.

In order for the listener of Fischer’s records to be able to more fully imagine his appearance, let us in conclusion give the floor to his eminent students. P. Badura-Skoda recalls: “He was an extraordinary man, literally radiating kindness. The main principle of his teaching was the requirement that the pianist should not withdraw into his instrument. Fischer was convinced that all musical achievements must be correlated with human values. “A great musician is first of all a personality. A great inner truth must live in him – after all, what is absent in the performer himself cannot be embodied in the performance, ”he did not get tired of repeating in the lessons.”

Fischer’s last student, A. Brendle, gives the following portrait of the master: “Fischer was endowed with a performing genius (if this obsolete word is still acceptable), he was endowed not with a composer’s, but precisely with an interpretive genius. His game is both absolutely correct and at the same time bold. She has a special freshness and intensity, a sociability that allows her to reach the listener more directly than any other performer I know. Between him and you there is no curtain, no barrier. He produces a delightfully soft sound, achieves cleansing pianissimo and ferocious fortissimo, which, however, are not rough and sharp. He was a victim of circumstances and moods, and his records give little idea of what he achieved in concerts and in his classes, studying with students. His game was not subject to time and fashion. And he himself was a combination of a child and a sage, a mixture of naive and refined, but for all that, all this merged into complete unity. He had the ability to see the whole work as a whole, each piece was a single whole and that is how it appeared in his performance. And this is what is called the ideal … “

L. Grigoriev, J. Platek